Understanding Sickle Cell Disease

CDC’s Role in Surveillance, Education, and Awareness

Download and print this page [PDF – 318 KB]

New, timely national data will allow for a better understanding of the state of sickle cell disease (SCD) in the United States.

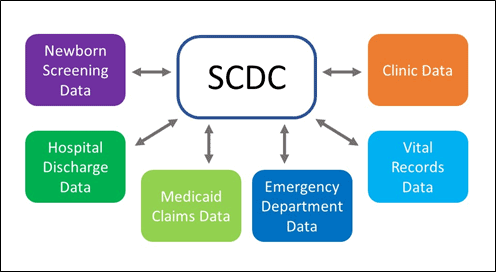

The Sickle Cell Data Collection (SCDC) program collects information about people with SCD to help communities, healthcare providers, policy makers, researchers, and federal, state, and local health agencies better understand who has SCD, what their healthcare needs are, and what barriers prevent them from receiving all their needed healthcare services. These data are used to target and develop strategies to improve access to the healthcare system and, ultimately, to improve health for people with SCD.

How does SCDC Work?

CDC works with SCDC states to collect and link data from several sources. This SCDC information paints a picture of where people with SCD are located, how they access healthcare, what their measures of poor health are, and more.

SCD is a group of inherited blood disorders that is estimated to affect more than 100,000 Americans. SCD causes the red blood cells to become

hard and sticky and look like the letter “C.” These misshapen red blood cells get stuck and clog blood flow, possibly leading to severe pain, kidney disease, stroke, and other serious health problems.

People with severe SCD may die more than 20 years before their peers, and often are unable to access the kind of quality health care that would help them live longer, healthier lives.

Public health surveillance is essential for any disease because it helps

- Healthcare providers understand how people interact with the healthcare system and how these factors impact health in the short and long term;

- Researchers and public health professionals know where to target activities and programs that will result in improvement in health care, including better access to new treatments or cures; and

- Policymakers and administrators assign resources and assess programs to improve healthcare services and overall patient health.

What have we learned from the California and Georgia SCDC?

- SCDC has identified more than 12,000 people with SCD in CA and GA. That is more than 10% of the estimated number of people with SCD in the United States.

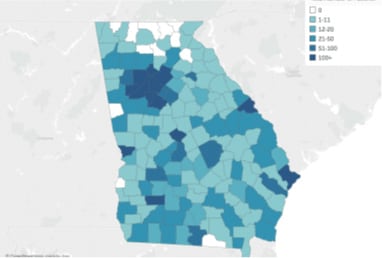

Map of people with SCD by county, Georgia, 2005

The GA SCDC team is working with hospitals and health departments to identify areas in which people with SCD receive little to no specialist care. The team is providing training for care providers in these counties so they can better help and treat those people in their towns and communities living with SCD.

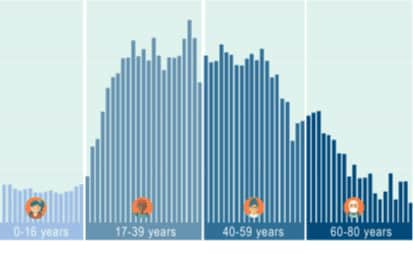

Emergency department visits among people with SCD in California, 2005-2014

The CA SCDC team use data to understand how, when, and where people with SCD seek care in emergency departments in their state. How frequently a patient uses the emergency department may point to gaps in the healthcare system, such as access to healthcare facilities and SCD healthcare expertise or insurance coverage. Researchers can study these data to better understand the changes in health care and policy that might lead to the improved quality of life, and longer life expectancy for, people with SCD.

If expanded to additional states, the SCDC program could be used in these ways and many more, to reduce poor health outcomes, prevent complications, inform healthcare needs for this population and support healthcare planning, and support the needs of federal partners who are researching best practices, treatments and, eventually, a cure for SCD. Data from multiple states could be compared to understand the similarities and differences between states, with regard to health and access to health care for people with SCD. These findings could lead to improved policies, increased resources, and enhanced programs.