Outbreaks Associated with Treated Recreational Water — United States, 2000–2014

Weekly / May 18, 2018 / 67(19);547–551

Michele C. Hlavsa, MPH1; Bryanna L. Cikesh, MPH1,2; Virginia A. Roberts, MSPH1; Amy M. Kahler, MS1; Marissa Vigar, MPH1,2; Elizabeth D. Hilborn, DVM3; Timothy J. Wade, PhD3; Dawn M. Roellig, PhD1; Jennifer L. Murphy, PhD1; Lihua Xiao, DVM, PhD1; Kirsten M. Yates, MPH1; Jasen M. Kunz, MPH4; Matthew J. Arduino, DrPH5; Sujan C. Reddy, MD5; Kathleen E. Fullerton, MPH1; Laura A. Cooley, MD6; Michael J. Beach, PhD1; Vincent R. Hill, PhD1; Jonathan S. Yoder, MPH1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationSummary

What is already known about this topic?

Outbreaks associated with treated recreational water can be caused by pathogens or chemicals.

What is added by this report?

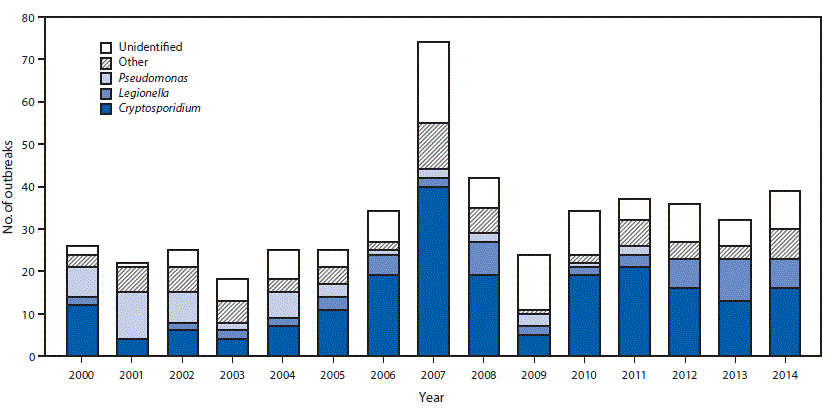

During 2000–2014, 493 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water caused at least 27,219 cases and eight deaths. Outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium increased 25% per year during 2000–2006; however, no significant trend occurred after 2007. The number of outbreaks caused by Legionella increased 14% per year.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The aquatics sector, public health officials, bathers, and parents of young bathers can take steps to minimize risk for outbreaks. The halting of the increase in outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium might be attributable to Healthy and Safe Swimming Week campaigns.

Altmetric:

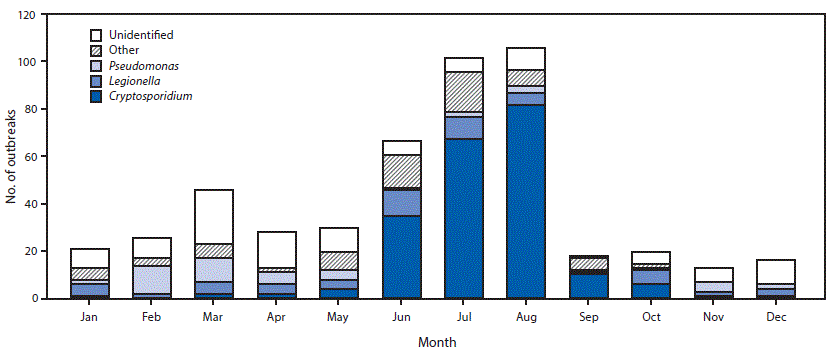

Outbreaks associated with exposure to treated recreational water can be caused by pathogens or chemicals in venues such as pools, hot tubs/spas, and interactive water play venues (i.e., water playgrounds). During 2000–2014, public health officials from 46 states and Puerto Rico reported 493 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water. These outbreaks resulted in at least 27,219 cases and eight deaths. Among the 363 outbreaks with a confirmed infectious etiology, 212 (58%) were caused by Cryptosporidium (which causes predominantly gastrointestinal illness), 57 (16%) by Legionella (which causes Legionnaires’ disease, a severe pneumonia, and Pontiac fever, a milder illness with flu-like symptoms), and 47 (13%) by Pseudomonas (which causes folliculitis [“hot tub rash”] and otitis externa [“swimmers’ ear”]). Investigations of the 363 outbreaks identified 24,453 cases; 21,766 (89%) were caused by Cryptosporidium, 920 (4%) by Pseudomonas, and 624 (3%) by Legionella. At least six of the eight reported deaths occurred in persons affected by outbreaks caused by Legionella. Hotels were the leading setting, associated with 157 (32%) of the 493 outbreaks. Overall, the outbreaks had a bimodal temporal distribution: 275 (56%) outbreaks started during June–August and 46 (9%) in March. Assessment of trends in the annual counts of outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium, Legionella, or Pseudomonas indicate mixed progress in preventing transmission. Pathogens able to evade chlorine inactivation have become leading outbreak etiologies. The consequent outbreak and case counts and mortality underscore the utility of CDC’s Model Aquatic Health Code (https://www.cdc.gov/mahc) to prevent outbreaks associated with treated recreational water.

An outbreak associated with recreational water is the occurrence of similar illnesses in two or more persons, epidemiologically linked by location and time of exposure to recreational water or to pathogens or chemicals aerosolized or volatilized from recreational water into the surrounding air. Public health officials in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, and Freely Associated States* voluntarily report outbreaks associated with recreational water to CDC. This report focuses on data in two groups of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water: 1) those that started during 2000–2012 and were previously summarized (1) and 2) those that started during 2013–2014 and were electronically reported to the Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System (WBDOSS)† by December 31, 2015 (https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/rec-water-tables-figures.html). Data on each outbreak included case count,§ number of deaths, etiology, setting (e.g., hotel) and venue (e.g., pool, hot tub/spa) where the exposure occurred, and earliest illness onset date. Poisson regression analysis was conducted to assess the trend in the annual counts of outbreaks, except when overdispersion required the use of negative binomial regression analysis.

During 2000–2014, public health officials from 46 states and Puerto Rico reported 493 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water, which resulted in at least 27,219 cases (Table) and eight deaths. Etiology was confirmed for 385 (78%) outbreaks. Among these, 363 (94%) were caused by pathogens (including four caused by both Cryptosporidium and Giardia) and resulted in at least 24,453 cases. Twenty-two (6%) outbreaks were caused by chemicals and resulted in at least 1,028 cases. Among the 363 outbreaks with a confirmed infectious etiology, 212 (58%) were caused by Cryptosporidium, 57 (16%) by Legionella, and 47 (13%) by Pseudomonas. Of the 24,453 cases, 21,766 (89%) were caused by Cryptosporidium, 920 (4%) by Pseudomonas, and 624 (3%) by Legionella. Of the 212 outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium, 24 (11%) each affected >100 persons; four of these outbreaks each affected ≥2,000 persons. At least six of the eight deaths,¶ which all occurred after 2004, were in persons affected by outbreaks caused by Legionella.

Hotels** (i.e., hotels, motels, lodges, or inns) were the leading setting associated with 157 (32%) of the 493 outbreaks. Of the 157 hotel-related outbreaks, 94 (60%)†† had a confirmed infectious etiology, 40 (43%) were caused by Pseudomonas, 29 (31%) by Legionella, and 17 (18%) by Cryptosporidium.§§ Sixty-five (41%) hotel-related outbreaks were associated with hot tubs/spas, and 47 (30%) started during February–March. Among all 493 outbreaks, a bimodal temporal distribution was observed. The 275 (56%) outbreaks that started during June–August were predominantly caused by Cryptosporidium, whereas the 46 (9%) that started in March were predominantly caused by an unidentified etiology or pathogens other than Cryptosporidium (Figure 1). Negative binomial regression analysis indicated that during 2000–2007, the annual number of outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium increased by an average of 25% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 7%–45%) per year (Figure 2). No significant trend was found after 2007.¶¶ Poisson regression analysis indicated that during 2000–2014 the annual number of outbreaks caused by Legionella increased by an average of 13% (95% CI = 6%–21%) per year, and the annual number of Pseudomonas folliculitis outbreaks (a total of 41 outbreaks during 2000–2014) decreased by an average of 22% (95% CI = 14%–29%) per year.***

Discussion

Approximately 500 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water occurred in the United States during 2000–2014. The most frequently reported outbreak setting was hotels. Approximately half of the outbreaks started during June–August, followed by a smaller peak in March. The second peak might reflect swimming’s transition from an only-summertime to a year-round activity, as the relative number of indoor versus outdoor treated recreational water venues increases. The aquatics sector and public health can voluntarily adopt CDC’s Model Aquatic Health Code to improve the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of public (nonbackyard) treated recreational water venues to prevent illness and injury.

Chlorine is the primary barrier to the transmission of pathogens in treated recreational water. At CDC-recommended concentrations of at least 1 ppm,††† free available chlorine inactivates most pathogens within minutes although extremely chlorine-tolerant Cryptosporidium can survive for >7 days (2,3). Cryptosporidium is transmitted when a diarrheal incident (i.e., a high-risk Cryptosporidium contamination event) occurs in the water and the contaminated water is ingested. The parasite’s extreme chlorine tolerance enables it to persist in water, cause outbreaks that sicken thousands, and spread to multiple recreational water venues and other settings (e.g., child care settings). Rates of individual cases caused by Cryptosporidium peak in the summer, coinciding with the summer swim season (4).

In contrast, Legionella and Pseudomonas are effectively controlled by halogens (e.g., chlorine and bromine) in well-maintained treated venues. However, because these pathogens can persist in biofilm (where microbial cells inhabit a primarily polysaccharide matrix, the cells cannot be removed from a surface by gentle rinsing) (5), and they are protected from inactivation and amplify when disinfectant concentrations are not properly maintained. Approximately 20% of 13,864 routine inspections of public hot tubs/spas conducted in 16 jurisdictions in 2013 identified improper disinfectant concentrations (6). Legionella is typically transmitted when aerosolized water droplets (e.g., produced by hot tub/spa jets) containing this bacterium are inhaled, whereas Pseudomonas is transmitted when skin comes in contact with contaminated water. Multiple factors contribute to Legionella and Pseudomonas growth in hot tubs/spas, including inadequate disinfectant concentration; warm (77°F–108°F [25°C–42°C]) water temperatures (which facilitate pathogen amplification and make it difficult to maintain adequate disinfectant concentration); water aeration (which depletes halogens); and the presence of biofilm on wet venue surfaces, scale, and sediment (7). The increasing annual rate of Legionnaires’ disease cases (286% during 2000–2014) (8), and possibly, the significantly increasing annual number of outbreaks caused by Legionella, might be associated with increasing size of susceptible populations (persons aged ≥50 years or those with chronic disease [particularly chronic lung disease] or who are immunocompromised; current or former smokers; or cancer patients), and increased Legionella growth in the environment, as well as increased awareness of the disease with improved testing and reporting (8). The significantly decreasing number of annual Pseudomonas folliculitis outbreaks might reflect an actual decrease or possibly focusing on hot tub/spa remediation to prevent further transmission rather than outbreak investigation and reporting.

If a diarrheal incident occurs in treated recreational water or an outbreak at least suspected to be caused by Cryptosporidium occurs, CDC recommends hyperchlorination, i.e., chlorinating water to achieve 3-log10 (99.9%) Cryptosporidium inactivation§§§ (https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/aquatics-professionals/fecalresponse.html). Alternatively, ultraviolet light or ozone systems can be added to inactivate Cryptosporidium, particularly in venues at increased risk for contamination (e.g., those intended for children aged <5 years, who might have limited or no toileting skills). As in any public setting, treated venues in the hotel setting should be operated and maintained by a trained operator or responsible supervisor.¶¶¶ These and other recommendations can be found in CDC’s Model Aquatic Health Code. CDC also provides specific recommendations for disinfecting hot tubs/spas contaminated with Legionella (https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/hot-tub-disinfection.pdf). Investigations of Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks indicate that effective water management programs for buildings and treated recreational water venues (e.g., hot tubs/spas) at increased risk for Legionella growth and transmission can reduce the risk for Legionnaires’ disease (8,9).

The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, the outbreak counts presented likely underestimate the actual incidence, in part because of variation in public health capacity and reporting requirements across jurisdictions. Second, reporting and review procedures (e.g., increased completeness of data on outbreaks caused by Legionella) changed over time, which affects the ability to compare data across years.

Addressing the challenges presented by chlorine-tolerant and biofilm-associated pathogens require sustained attention to improving design, construction, operation, and management of public treated recreational water venues. This includes educating the public. Preventing Cryptosporidium contamination is critical to preventing transmission. Thus, the key message to the public, particularly parents of young bathers, is “Don’t swim or let your kids swim if sick with diarrhea.” Preventing transmission of Legionella, Pseudomonas, and other chlorine-susceptible pathogens means educating bathers and parents of young bathers to check the inspection scores of public treated recreational water venues and conduct their own mini-inspection before getting into the water (e.g., measure bromine or free chlorine level and pH with test strips, which can be purchased at pool supply, hardware, and big-box stores). Potential hot tub/spa users should know whether they are at increased risk for Legionnaires’ disease, so they can choose to avoid hot tubs/spas, as indicated (https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/fs-legionnaires.pdf). The halting of the substantial increase in annual numbers of outbreaks caused by Cryptosporidium might, at least in part, be because of local, state, and federal Healthy and Safe Swimming Week (the week before Memorial Day) campaigns (10). Thus, the focus of these campaigns could regularly be expanded beyond preventing Cryptosporidium transmission in an effort to prevent other recreational water outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

State, territorial, local, and Freely Associated State waterborne disease coordinators, epidemiologists, and environmental health practitioners; Gordana Derado, Sarah A. Collier, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported.

Corresponding author: Michele C. Hlavsa, mhlavsa@cdc.gov, 404-718-4695.

1Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 2Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee; 3Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.; 4Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services, National Center for Environmental Health; 5Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 6Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC.

* Includes Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau.

† 2013–2014 were the last years for which finalized data were available. For more information on WBDOSS, visit https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/index.html; outbreaks resulting from recreational water exposures on cruise ships are not reported to WBDOSS.

§ Based on the estimated number of primary cases. For outbreaks that started before 2009, if both the actual and estimated case counts were reported, the estimated case count was used if the population was sampled randomly or the estimated count was calculated by applying the attack rate to a standardized population.

¶ The two remaining deaths were in persons affected by an outbreak caused by an etiology that was unidentified but suspected to be Legionella.

** Other settings: community/municipality/public park (115 [23%] outbreaks), club/recreational facility (68 [14%]), waterpark (54 [11%]), private residence (31 [6%]), subdivision/neighborhood (21 [4%]), school/college/university (14 [3%]), unidentified (13 [3%]), camp/cabin setting (nine [2%]), child care/daycare center/day camp (six [1%]), health care facility (three [1%]), and other (two [0%]). Categories were not consistently used or defined over the study period.

†† Approximately half (60 [56%]) of the 108 outbreaks with an unidentified etiology were associated with the hotel setting. Among the 60 outbreaks, 23 (38%) started during March–April; 41 (68%) were outbreaks of skin-related illness.

§§ The remaining eight outbreaks were caused by norovirus (five [5%] outbreaks), Bacillus (one [1%]), nontuberculous mycobacterium (one [1%]), and Staphylococcus (one [1%]).

¶¶ The 2007 number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water and caused by Cryptosporidium (40), and thus, of outbreaks overall might be outliers. For 2007, Utah reported a statewide outbreak primarily associated with treated recreational water and caused by Cryptosporidium; neighboring states reported additional outbreaks associated with recreational water and caused by Cryptosporidium. All of these individual outbreaks might have been a single multistate outbreak. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6012a1.htm.

*** Because of concerns that folliculitis might not be cultured, which means the etiology cannot be identified, a Poisson regression analysis was conducted to assess the annual number of outbreaks of skin-related illness caused by Pseudomonas or an unidentified etiology. The annual number of outbreaks decreased by 5% (95% CI = 1%–9%).

††† At water pH ≤7.5 and temperature ≥77°F (25°C).

§§§ At water pH ≤7.5 and temperature ≥77°F (25°C), 3-log10 Cryptosporidium inactivation can be achieved in the absence of cyanuric acid (which prevents chlorine degradation by the sun’s ultraviolet light but substantially delays pathogen inactivation) by maintaining free available chlorine at 20 ppm for 12.75 hours and in the presence of 1–15 ppm cyanuric acid by maintaining free available chlorine at 20 ppm for 28 hours.

¶¶¶ Trained operators are those who have successfully completed an approved operator training course; responsible supervisors are those who can conduct and record results of water quality testing, properly maintain water quality, perform general maintenance procedures, and identify when to close venues to protect public health.

References

- CDC. Surveillance reports for recreational water–associated disease & outbreaks. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/surveillance/rec-water-surveillance-reports.html

- Shields JM, Hill VR, Arrowood MJ, Beach MJ. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum under chlorinated recreational water conditions. J Water Health 2008; 6:513–20. CrossRef PubMed

- Murphy JL, Arrowood MJ, Lu X, Hlavsa MC, Beach MJ, Hill VR. Effect of cyanuric acid on the inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum under hyperchlorination conditions. Environ Sci Technol 2015;49:7348–55. CrossRef PubMed

- Painter JE, Hlavsa MC, Collier SA, Xiao L, Yoder JS; CDC. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Suppl 2015;64(No. Suppl 3). PubMed

- Donlan RM. Biofilms: microbial life on surfaces. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:881–90. CrossRef PubMed

- Hlavsa MC, Gerth TR, Collier SA, et al. Immediate closures and violations identified during routine inspections of public aquatic facilities—Network for Aquatic Facility Inspection Surveillance, five states, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65(No. SS-5). CrossRef PubMed

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Minimizing the risk of legionellosis associated with building water systems: ASHRAE guideline 12-2000. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers; 2000.

- Garrison LE, Kunz JM, Cooley LA, et al. Vital signs: deficiencies in environmental control identified in outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease—North America, 2000–2014. Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:576–84. CrossRef PubMed

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Legionellosis: risk management for building water systems: ANSI/ASHRAE standard 188–2015. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers; 2015.

- CDC. Promotion of healthy swimming after a statewide outbreak of cryptosporidiosis associated with recreational water venues—Utah, 2008–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:348–52. PubMed

Abbreviation: MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

* Not applicable because only one outbreak was nationally reported for that etiology.

FIGURE 1. Number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and month — United States, 2000–2014*

FIGURE 1. Number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and month — United States, 2000–2014*

* Includes outbreaks with the following etiologies: Bacillus, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, nontuberculous mycobacteria, Salmonella, Shigella, Staphylococcus, Giardia, echovirus, norovirus, or excess chlorine/disinfection by-product/altered pool chemistry.

The bar chart above shows the number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and month in the United States during 2000–2014.

FIGURE 2. Number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and year — United States, 2000–2014

FIGURE 2. Number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and year — United States, 2000–2014

* Includes outbreaks with the following etiologies: Bacillus, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, nontuberculous mycobacteria, Salmonella, Shigella, Staphylococcus, Giardia, echovirus, norovirus, or excess chlorine/disinfection by-product/altered pool chemistry.

The bar chart above shows the number of outbreaks associated with treated recreational water (N = 493), by etiology and year in the United States during 2000–2014.

Suggested citation for this article: Hlavsa MC, Cikesh BL, Roberts VA, et al. Outbreaks Associated with Treated Recreational Water — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:547–551. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6719a3.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.