Things to Consider: Outbreak Investigations

The following considerations are not exhaustive but are intended to help epidemiologists and other public health officials make decisions as they investigate common outbreak scenarios.

The investigative steps described below are not linear. Public health officials may have already performed several steps during their routine evaluation of Legionnaires’ disease case reports. Many of these steps will occur simultaneously or in a sequence that varies during the course of an investigation.

Every outbreak investigation is unique and requires careful planning and periodic reassessments to determine the most appropriate response, with consideration given to personnel, resources, or other competing priorities within the state, territorial, or local health department. CDC is available for consultation and assistance.

General Considerations

Do You Need to Conduct a Full Investigation?

The first step is to determine if a full investigation is needed. The setting can impact this decision. See the following sections for considerations specific to:

See Healthcare Investigation Resources to determine if you need to conduct a full investigation in a healthcare setting.

Clusters and outbreaks have the same definition for Legionella and you can use either term. Both terms describe two or more people with Legionnaires’ disease exposed to Legionella at the same place at about the same time (as defined by the investigators). However, your target audience (e.g., the general public, the media, building owners/managers, healthcare facility staff) may perceive the terms “cluster” and “outbreak” differently. It is up to you to decide how to use these terms, but, whatever you choose, use the terms consistently.

Steps Involved in a Full Investigation

Once public health officials have determined that they need to conduct a full investigation, there is a series of steps that should take place. During the course of a full investigation, public health officials should:

- Perform a retrospective review of the cases in the health department surveillance database to identify earlier cases with possible exposures to the same setting or geographic area

- Develop a line list of cases associated with the common exposure setting or geographic area

- Work with appropriate parties to identify additional cases (e.g., through retrospective review of medical or laboratory records) and facilitate testing for Legionella using both culture of lower respiratory secretions on media that supports growth of Legionella and the Legionella urinary antigen test

- Obtain post-mortem specimens, when applicable

- Consider recommendations for restricting water exposures or other immediate control measures

- Facilitate environmental assessment to evaluate possible environmental exposures

- Facilitate environmental sampling, as indicated by the environmental assessment

- Make recommendations for remediation of possible environmental source(s), if indicated

- Communicate with stakeholders as appropriate and develop a risk communications plan if necessary

- Determine how long heightened disease surveillance and environmental sampling should continue to ensure the outbreak is over

- Work with appropriate parties to develop or review and possibly revise the water management program

- Subtype and compare clinical and environmental isolates, if available

- Follow up to assess the effectiveness of implemented measures for Legionella control

The timeframe for defining an outbreak may vary depending circumstances and is ultimately deferred to the public health jurisdiction performing the investigation. CDC defines outbreaks associated with

- travel1

- healthcare

- potable water systems in other buildings at increased risk for Legionella growth and transmission

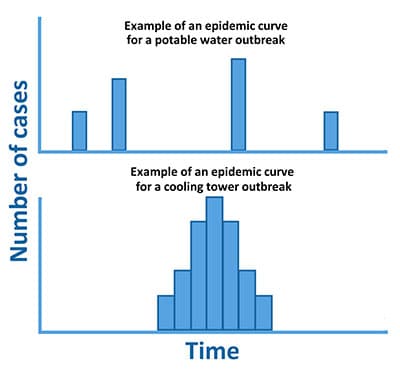

as two or more cases associated with the same possible source during a 12-month period. This definition increases sensitivity of outbreak detection, especially for outbreaks involving potable water, and helps account for periodic changes in risk (e.g., due to seasonality). Note that under certain circumstances, the timeframe under consideration may be shorter, such as during cooling tower outbreaks, which tend to be more explosive and of shorter duration (e.g., 3 months).

1 Smith P, Moore M, Alexander N, et al. Surveillance for travel-associated Legionnaires disease — United States, 2005–2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1261–3.

See Healthcare Investigation Resources for more information about key elements in a full investigation involving a healthcare facility.

In general, state, territorial, and local health departments are best positioned to provide oversight for each step of the investigation process to ensure adherence to public health recommendations. However, if the health department does not have the necessary resources to conduct all of the steps, they may defer certain responsibilities to the owner/manager of the building. For example, the health department may not have personnel with environmental expertise specific to Legionella or essential equipment.

In some situations, hiring professionals with specific expertise in managing Legionella bacteria in building water systems may also be helpful. See these factors to consider when working with Legionella consultants. The CDC Legionella team is available to assist, either remotely or in person (see Request CDC Assistance for more information).

Control Measures for Potable Water Outbreaks

If a building’s potable water (i.e., water used for drinking and bathing) is thought to be a source of Legionella transmission, consider taking measures to reduce the possibility of ongoing transmission to susceptible individuals. This could include implementing water restrictions and/or installing point-of-use filters, either globally or in areas of greatest risk. You should tailor options to the structural characteristics of the building and circumstances of the outbreak. See Immediate Control Measures for Healthcare Facilities for more specific information about protecting patients in healthcare settings.

Examples of immediate control measures include:

- Restricting showers (using sponge baths instead)

- Avoiding exposure to hot tubs

- Installing point-of-use microbial filters with an effective pore size of 0.2 microns or less that comply with the requirements of ASTM F838 on any showerheads or sink/tub faucets intended for use

- Understand manufacturer recommendations regarding the temperature, pressure, and chemical levels that filters can withstand and suggested frequency for replacement

- Confirm if filters need to be removed during acute remediation procedures

- Halting new admissions or temporarily closing the building, affected area, or device

- Ensuring that contingency responses and corrective actions are implemented if the building already has a water management program

- Distributing notification letters to the appropriate audience(s); see Communications Resources for more information

Environmental Assessment

An environmental assessment is necessary to identify possible environmental sources of Legionella. The environmental assessment is a multi-step process that provides a thorough understanding of a building’s water system(s), as well as information about external building factors (e.g., construction, water main breaks, change in municipal water quality). It helps public health officials and building owners/managers identify and minimize risk factors for Legionella growth and transmission. An environmental assessment involves visual inspection and specialized monitoring of water quality parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, residual disinfectant). If possible, it should be conducted by people with experience in water management and knowledge of the ecology of Legionella.

During the assessment, recording the values of all water quality parameters on the CDC Sample Data Sheet [1 page] (or equivalent) is important. These parameters provide useful information about how the water quality changes within the building water system(s). It may also be helpful to note the time it takes the water from a fixture to achieve the highest or lowest temperature measured as an indication of system balance.

Additional environmental assessment resources are available. A consultant with Legionella-specific environmental expertise may sometimes be helpful when performing the environmental assessment.

Environmental Sampling

You can use the environmental assessment along with epidemiologic information to determine whether to conduct Legionella environmental sampling and to develop a sampling plan. The objective of Legionella environmental sampling during an outbreak is to identify potential sources of exposure as well as characterize the extent of Legionella colonization within the building water system(s). Environmental sampling is important for verifying that remediation activities are working to control the hazard. Environmental sampling is also important to establish the quantity of Legionella within the building water system(s) and the type of Legionella present for the purpose of future monitoring.

Legionella environmental sampling plans during an investigation are unique to each investigation and can be based on many factors such as:

- Findings from the environmental assessment

- Building characteristics (e.g., size, age, complexity, populations served)

- Sites of possible exposure to aerosolized water as determined by the epidemiologic investigation

- Available resources and supplies to support sampling

Additional environmental sampling resources are available. A consultant with Legionella-specific environmental expertise may sometimes be helpful when making decisions about environmental sampling. The sampling procedure guide [6 pages] describes how to obtain both bulk water and biofilm swab samples.

You should base where and how to collect samples on consideration of the following:

- Available epidemiologic information, such as possible case exposures to particular showerheads, sink faucets, or other devices

- If sampling devices, such as hot tubs, sink faucets, or showerheads, in response to possible case exposures, biofilm swab results can provide information about amplification potential within a device.

- Locations that are representative of the implicated building water system(s), guided by the environmental assessment and a comprehensive understanding of the building water system(s) (e.g., near the building water entry, water heaters and/or storage tanks, representative points-of-use, hot water return line, associated devices)

- Multiple factors (e.g., environmental assessment results, trends in water management program performance, including previous Legionella sampling results) should be considered when deciding whether to sample hot versus cold water systems (or both).

- Where multiple individual water systems are present, each water system should be represented separately in the sampling plan.

- If sampling cooling towers, hot tubs, or decorative fountains, always collect swab samples of the waterline, inside the jets, and of any visible biofilm.

- Presence of filters (e.g., sand, cartridge)

- Locations where water parameters measured during the environmental assessment indicate risk for Legionella growth and transmission to evaluate the potential for amplification/transmission

- Feasibility given time and resource constraints of the group performing the investigation

When determining the appropriate water sample volume to collect, consider the following:

- Whenever possible, a collection of one liter of water is preferred. You will occasionally need larger volumes of water (1 to 10 liters) to detect Legionella in water that has very low concentrations of these bacteria, such as municipal water supplies. If you cannot collect a liter from a sample source, a smaller volume is acceptable.

- Ensure that the laboratory processes an appropriate volume for the type of sample collected and the test conducted. For instance, processing a full liter for culture is preferred for potable water, while smaller volumes from samples of open water sources such as fountains and cooling towers are typically plated directly.

- Note: 250 mL is the minimum recommended sample volume for routine environmental sampling of potable water for Legionella in the absence of cases.1

During a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak investigation, laboratories may suddenly be faced with processing hundreds of samples. CDC’s Developing a Legionnaires’ Disease Laboratory Response Plan Toolkit helps public health laboratories prepare for an effective response during a Legionnaires’ disease investigation. If environmental sampling for Legionella is not available through the state, territorial, or local public health laboratory, there are a number of considerations for selecting a laboratory including:

- Does the laboratory have documentation of successful performance from a proficiency test program, such as the ELITE Program?

- Is the laboratory accredited by a national program for environmental testing?

- Does the laboratory routinely perform culture for Legionella?

- What level of identification (species/serogroup) can the laboratory perform?

- Is the laboratory willing to save samples and isolates and share them with public health laboratories if requested during an outbreak investigation?

Remediation

Remediation may be required immediately to minimize the risk of Legionella growth and transmission. Tailor the remediation to structural characteristics of the facility and circumstances of the outbreak. Remediation options can include:

- Hyperchlorinating the potable water system

- Flushing unused plumbing outlets

- Draining and scrubbing devices

- Superheating and flushing a simple device. Note, ASHRAE Guideline 12-2020 recommends against superheating as a remediation method for potable water systems.

You should base decisions on findings from the environmental assessment, sampling results, and epidemiologic findings of the investigation. See General Guidelines for additional remediation resources. It may sometimes be necessary to hire a consultant with Legionella-specific environmental expertise to help make decisions about or perform remediation.

Subtyping and Comparing Isolates

- Legionella is a diverse genus, although L. pneumophila serogroup 1 causes most cases of Legionnaires’ disease. During an investigation, it is common to find more than one type of Legionella in several possible sources. If you identify Legionella strains other than the presumptive outbreak strain through environmental sampling, you should consider this as evidence that conditions supporting Legionella growth and transmission exist within the building water system(s).

- Most state laboratories will be able to provide identification of Legionella to the species and serogroup level (if L. pneumophila). It is necessary to characterize Legionella found in the environment to help confirm the source of the outbreak. Commercial laboratories may be able to determine the species and serogroup.

- Molecular comparisons of Legionella isolates recovered from clinical specimens and possible environmental sources are useful aspects of Legionnaires’ disease outbreak investigations. In particular, genome sequence data can provide high-resolution information on the relatedness of such isolates. Combined with patient exposure information, these data can further support the identification of a specific environmental source.

When Is the Outbreak Over?

Public health officials performing the investigation will need to make decisions about the end of an outbreak on a case-by-case basis. Possible considerations include:

- No new cases of Legionnaires’ disease identified during a period of careful monitoring for new cases

- No new cases of Legionnaires’ disease following implementation of long-term Legionella control strategies as part of a water management program

- No detection of Legionella in post-remediation environmental samples*

Before you can consider an outbreak over, an effective water management program to prevent ongoing transmission of Legionella should be in place. You can extend the timeframe for enhanced environmental and clinical surveillance following an outbreak at any point if public health officials have concern for the potential for ongoing transmission of Legionella. Concerns about the potential for ongoing transmission would be based on factors such as Legionella-positive environmental cultures, new cases of Legionnaires’ disease, or suboptimal performance of the water management program.

*If you have confirmed an outbreak strain, efforts to monitor the building water system(s) can focus on the outbreak strain. However, identification of other Legionella species or serogroups, indicates conditions support the growth of Legionella. All Legionella species or serogroups are potentially pathogenic. Therefore, you should consider needed adjustments to the water management program.

Special Considerations: Possible Sources of Exposure

Potable Water

- Potable water is a common source for Legionella outbreaks. Potable water outbreaks are typically less “explosive” than outbreaks associated with cooling towers. However, without remediation, building water systems colonized with Legionella may cause disease over years before a problem is recognized.3,4

- Potable water can come from either a public utility or from a private source. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates public water quality and requires a minimum amount of disinfectant to be present (i.e., disinfectant residual). Building owners are responsible for maintaining the quality of the water once it enters the building water system(s).2 However, buildings that have their own disinfection systems may also be subject to EPA and/or state regulations. Water quality, including disinfectant level, can drop as water travels through building water systems. Residual disinfectant supplied by the public utility is lost as organic matter consumes it, it naturally off-gases, and as water ages. Heating the water speeds up loss of residual disinfectant in pipes or fixtures.

- Treatment plants sometimes switch from one type of disinfectant to another, based on seasonal changes, or one-time changes in treatment methods. These changes can affect Legionella growth.

- Showerheads are only one possible source of potable water exposure. Spending time near sink faucets and aspiration of drinking water or ice chips are possible routes of transmission, particularly among immunocompromised patients.

Cooling Towers

This resource explains various ways to locate cooling towers quickly and accurately within a geographic area. Find out more about these identification methods.

- A cooling tower is a structure that contains water and a fan as a part of a centralized air cooling system for a building or industrial processes. Cooling towers remove unwanted heat from the system by exposing heated water to cooler air. In contrast, home AC units do not use water to cool, so they do not aerosolize water and are not a risk for Legionella growth and spread.

- In areas with many buildings, identifying all cooling towers can be challenging. However, some areas are starting to require registration of cooling towers to track their locations. Using Geospatial Information Systems (GIS) technology may be useful for aerial cooling tower identification. Sometimes certain entities, such as water utility companies, may provide permits for cooling towers and have location information.

- Some cooling towers are located on the ground or on sides of buildings and may be difficult to see from aerial photography. A physical assessment, street view imagery, or checking with building owners and managers is necessary in some circumstances. Learn about Procedures for Identifying Cooling Towers.

- If you implicate a cooling tower as a possible source of exposure, ensure that it has been shut down, but not drained or hyperchlorinated, before sampling.

Hot Tubs and Pools

This Health Advisory provides guidance for environmental and public health practitioners to minimize risk for Legionella exposure from hot tub displays at temporary events (e.g., fairs, home and garden shows, conventions).

- Being in or near a hot tub or hydrotherapy tub while it is turned on is a possible exposure risk because of the ability to aerosolize water containing Legionella.

- If you implicate a hot tub as a possible source of exposure, ensure that it has been turned off, but not drained, before sampling.

- Legionella are unlikely to grow in typical swimming pools because water temperatures are usually too cold. However, you should sample pools if they are associated with a possible exposure or temperatures are within the permissive range (i.e., 77–113°F).

Decorative Fountains

- Decorative fountains are a possible exposure source for Legionella, particularly in enclosed spaces.

- Submerged lighting and warm ambient temperatures in fountains can contribute to Legionella growth.

- If you implicate a fountain as a possible source of exposure, ensure that it has been turned off, but not drained, before sampling.

Special Considerations: Travel-associated Outbreaks

CDC defines travel-associated outbreaks as two or more Legionnaires’ disease cases associated with the same travel accommodation in a 12-month period.

Do You Need to Conduct a Full Investigation?

Conduct a full investigation if:

- You have identified two or more cases of Legionnaires’ disease or Pontiac fever in people who

- Stayed overnight in the same accommodation during the exposure period for Legionnaires’ disease (14 days before date of symptom onset) or Pontiac fever (typically 24–72 hours before date of symptom onset)

AND - Had symptom onsets within 12 months of each other

- Stayed overnight in the same accommodation during the exposure period for Legionnaires’ disease (14 days before date of symptom onset) or Pontiac fever (typically 24–72 hours before date of symptom onset)

Consider conducting a full investigation if:

- You have identified cases in association with the same accommodation over a period of several years (i.e., greater than 12 months). Potable water outbreaks may not be as obvious as cooling tower outbreaks, which tend to cause cases that are more tightly clustered in time. Without remediation, building water systems colonized with Legionella may cause sporadic-appearing cases over years before a problem is recognized.3,4

- You have identified a single case following a previously recognized outbreak at the same accommodation.

- You have identified cases in person(s) who spent time at the accommodation, but were not overnight guests (i.e., staff or visitors).

If you do not consider the available epidemiologic evidence strong enough to warrant environmental sampling, consider at least conducting an environmental assessment. An environmental assessment can help determine if conditions for Legionella growth exist in the building water system(s) where the patient(s) may have been exposed. The environmental assessment findings can then inform a decision about sampling for Legionella. Ask the accommodation owner/manager whether the building has a water management program. If the building should have a water management program and does not have one, provide information about water management programs and encourage implementation. See Prevention through Water Management Programs for more information.

Specific Activities for Travel-associated Outbreaks

Obtain a Detailed Exposure History and Identify Patterns

- Ensure that you have obtained as detailed of an exposure history as possible for each case from the patient or a proxy. CDC’s Legionnaires’ Disease Hypothesis-generating Questionnaire Template [12 pages] is a useful tool to help gather this information. Sometimes a second interview can be helpful using a modified questionnaire based on new information that you have gathered during the course of the investigation.

- CDC’s Line List Template is a helpful tool to summarize case demographic, clinical, and exposure information specific to a travel-associated outbreak.

Conduct Additional Case Finding for Travel-associated Cases

- Notify CDC of the outbreak via travellegionella@cdc.gov. CDC staff can search the Supplemental Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance System (SLDSS) for additional cases among people who reported staying at the accommodation during their exposure periods.

- Submit an Epi-X call for cases to alert other states and request that they immediately report any additional cases associated with the accommodation to the investigating state, territorial, or local health department. If you do not have contributor access to Epi-X, email travellegionella@cdc.gov for support.

Communicate with Travel Accommodation Owners/Managers

- Notify the accommodation manager or owner about the outbreak. Ask management whether they are aware of any guests or employees who have reported Legionnaires’ disease symptoms or illness. Ask management to report any consistent illnesses to the health department. See Communications Resources for more information.

- Depending upon the circumstances, consider notifying incoming guests and staff about possible exposure to Legionella and symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. Encourage them to speak with their physician if they develop symptoms.

- If the cases were recent, request a guest list for the prior investigation time period. Consider notifying past guests of their possible exposure to Legionella if they may still be within the exposure period or recently developed illness, as it may prompt them to seek care earlier if they experience symptoms.

- Review employee absentee data and/or employee clinic records to obtain information about clinically compatible illnesses among staff.

Special Considerations: Community-associated Outbreaks

CDC defines community-associated outbreaks as an increase in Legionnaires’ disease cases in a certain geographic area beyond what one would normally expect for the same time and place.

Do You Need to Conduct a Full Investigation?

Conduct a full investigation if:

- You have identified one or more cases of Legionnaires’ disease at a correctional facility or other facility where people cannot leave the premises (and therefore spent the entire exposure period there). In general, you should treat outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease at such facilities with the same considerations as healthcare-associated outbreaks.

Consider conducting a full investigation if:

- You have analyzed available data and found an increase in Legionnaires’ disease in a certain geographic area (e.g., comparing 5-year average rate of Legionnaires’ disease to the current incidence).

If available epidemiologic evidence is not strong enough to warrant environmental sampling, consider at least conducting an environmental assessment. An environmental assessment can help determine if conditions for Legionella growth exist in the building water system(s) where the case(s) may have been exposed. The environmental assessment findings can then inform a decision about sampling for Legionella. In some situations, the first step in an investigation will be to identify possible sites of exposure, like cooling towers or fountains.

Specific Activities for Community-associated Outbreaks

Obtain a Detailed Exposure History and Identify Patterns

- Ensure that you have obtained as detailed of an exposure history as possible for each case from the patient or a proxy. CDC’s Legionnaires’ Disease Hypothesis-generating Questionnaire Template [12 pages] is a useful tool to help gather this information. Sometimes a second interview can be helpful using a modified questionnaire based on new information that you have gathered during the course of the investigation.

- CDC’s Line List Template is a helpful tool to summarize case demographic, clinical, and exposure information specific to a community-associated outbreak.

Conduct Additional Case Finding for Community-associated Cases

- Notify local clinical laboratories and healthcare providers for additional case finding (e.g., issue a health advisory notification [HAN]). Provide guidance for appropriate diagnostic testing and encourage retention of clinical Legionella isolates.

Other Considerations

- Map all patient residences and sites for daily activities (e.g., work, shopping).

- Identify any possible common exposures through conducting patient interviews. To identify a wide range of possible exposures, consider interviewing patients using CDC’s Legionnaires’ Disease Hypothesis-generating Questionnaire Template [12 pages].

- Contact the local water authority to determine changes that could have contributed to Legionella growth (e.g., modifications to potable water disinfection, water main breaks, major construction activity, water service interruptions).

- Consider cooling towers as a possible source if cases are tightly clustered in time and neighborhood but patients lack common potable water exposures. See Procedures for Identifying Cooling Towers for more information.

Line List Templates

Use or adapt the following templates to organize and track summary case information for outbreaks in various settings.

Prevention with Water Management Programs

The key to preventing Legionnaires’ disease is to reduce the risk of Legionella growth and spread. Building owners and managers can do this by maintaining building water systems and implementing controls for Legionella. See Prevention with Water Management Programs for more information.

- Kozak NA, Lucas CE, Winchell JM. Identification of Legionella in the environment. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;954:3–25.

- ASHRAE. Legionellosis: Risk management for building water systems. ASHRAE Standard 188. Atlanta, GA: ASHRAE; 2015.

- Cowgill KD, Lucas CE, Benson RF, et al. Recurrence of Legionnaires’ disease at a hotel in the United States Virgin Islands over a 20-year period. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(8):1205–7.

- Silk BJ, Moore MR, Bergtholdt, et al. Eight years of Legionnaires’ disease transmission in travelers to a condominium complex in Las Vegas, Nevada. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(11):1993–2002.