Patient-Centered Care for Transgender People: Recommended Practices for Health Care Settings

Many transgender people experience stigma and discrimination in their day-to-day lives that can affect access to health care.1 In particular, many transgender women of color (specifically those who are black or African American and Hispanic or Latino) have reported being victims of harassment and violence, even in health care settings.1,2 Given these challenges, transgender people, especially transgender women of color, may delay seeking medical care because of fear or actual experience of negative treatment by health care staff.1,3

Transgender people may also have unique needs and concerns when interacting with the health care system. Transgender patients’ concerns often arise at the front desk and in waiting areas because those are the first points of contact for most patients. For instance, front desk staff may not know how to handle a situation in which patients’ legal names and genders differ from their preferred names and gender identities and/or expressions. This puts patients in the uncomfortable position of having to explain their transgender status to the front desk within hearing distance of other patients. Other issues, such as providers’ assumptions about sexual orientation and gender conformity, may arise during the clinical encounter. However, these issues are almost always unintentional and can be prevented by training all staff in basic principles and strategies. All members of the health care team, from front desk staff to clinicians, can play a role in creating an environment that respects and responds to the needs of transgender people. Providers can use the material here as a starting point for understanding how to provide affirming services for transgender patients. This information is organized into two parts:

- Understanding Transgender People and Their Health Needs provides important basic information on transgender people’s identities, lives, and health care needs. Gaining this knowledge is a critical first step in being able to serve transgender people in a transgender-affirming manner.

- Patient-Centered Strategies in Health Care provides tips and strategies to improve communication and create a more affirming environment for transgender people. Here health care providers will find tools they can act on immediately and use daily.

These materials can be:

- Used to help train all staff about transgender health (see Additional Resources for training opportunities)

- Distributed in new hire orientation packets

- Displayed as stand-alone items, such as the Communication Strategies and Scripts—Summary of Best Practices, at employee work stations.

Basic Concepts and Terms

From the Patient’s Perspective

Watch brief accounts from transgender peopleexternal icon of different ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds discuss their lives and their health care needs. This video provides a look at the diversity of the expressions and experiences of transgender people.

The term transgender has varying definitions across cultures and communities. Most describe transgender people as those who have a gender identity that is different from their sex assigned at birth. Sex assignment at birth is based on external genitalia, whereas gender identity refers to the internal sense of one’s gender. Although people use many different terms to describe themselves, in general, a transgender woman is someone who was listed as male on their birth certificate and whose gender identity is female, and a transgender man is someone who was listed as female on their birth certificate and whose gender identity is male. Other people may have a gender identity that is fluid or non-binary; their gender is neither male nor female, or it is a mix of male and female. Sexual orientation, which relates to emotional and sexual attraction to others, is distinct from gender identity; transgender people may have any sexual orientation regardless of their gender identity. For transgender people, the discordance between their gender identity and their assigned sex at birth can cause a great deal of distress. That is why it is important for transgender people to be able to access health care that is patient-centered.

Many—but not all—transgender people make changes to their physical appearance. This is sometimes called gender affirmation. These changes can include modifications to clothing, hairstyles, and mannerisms. Many will change their first name, and they may want others to refer to them by pronouns that correspond to their gender identity. It is estimated that about 60% to 70% of transgender people take hormones and that about 20% to 40% have had one or more gender-affirming surgeries to alter their physical characteristics.1,4 Decisions about medical or surgical treatments depend on personal choice and cost. (See Additional Resources for more on hormone and surgical treatments.)

How many people identify as transgender?

There are two recent estimates of population size ranging from 0.4% to 0.6%. The new estimates are larger than the previous estimate from roughly a decade ago.5,6 The analyses note several reasons that may account for this difference, including a perceived increase in visibility and social acceptance of transgender people, which may increase the number of individuals willing to identify as transgender on a government survey. It is also noted that younger adults aged 18 to 24 are more likely than older adults to say they are transgender.

Transgender Health Needs

The research on transgender people and their health needs is sparse. However, available studies indicate that transgender people experience multiple health disparities due to stigma, discrimination, and unique barriers to accessing quality care.7,8 A brief summary of the barriers to achieving positive health outcomes and the consequences of those barriers is presented below. The purpose of listing these is to build an understanding of the difficulties transgender people face so health care providers can help break down barriers.

Stigma and Discrimination

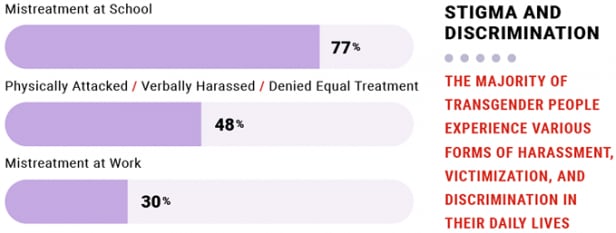

The majority of transgender people experience various forms of harassment, victimization, and discrimination in their daily lives.9

In addition to facing discrimination, transgender people are more likely than the general population to be homeless, un- or underemployed, and living below the federal poverty level.1,7

Unfortunately, transgender women of color face bias and discrimination on several fronts. For example, an African American transgender woman may face racism, stigma, and sexism in her daily life, with negative or deadly consequences for her health.10

Barriers to Accessing Care

Lack of trained providers

Because of expectations of discrimination or misunderstanding in medical settings, many transgender people avoid or delay seeing a health care provider. But even when they do access care, they have difficulty finding a provider or being referred to providers who have expertise in patient-centered care for transgender people. In one study, 50% of transgender people reported they felt the need to teach their doctors about transgender care.1

Lack of insurance

Many transgender people lack health insurance, have been denied insurance coverage of transition-related care, or denied coverage of preventive care that is not consistent with the gender their insurer has listed (e.g., coverage for a transgender woman to receive prostate exams may be denied if the patient’s gender is listed as female). Health insurance plans are not required to cover transition-related care, although some states have made this a requirement.

How Stigma, Discrimination, and Access Barriers Affect Transgender Health

The trauma and stress induced by stigma and discrimination, as well as the related effects of under- and unemployment, homelessness, lack of access to transition-related care and lack of insurance, among other issues, can create a great burden on the mental and physical health of transgender people.

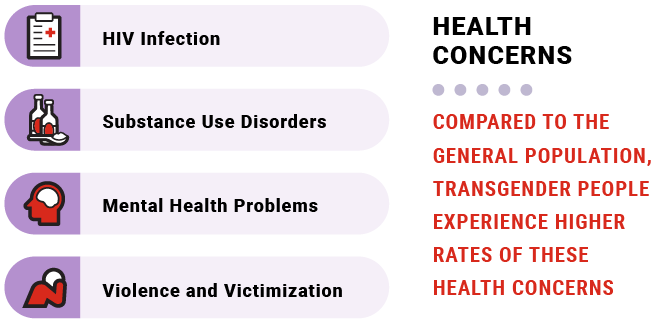

The graphic below illustrates research findings from several sources, including the National Academy of Medicine and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2020, which found that, compared to the general population, transgender people experience higher rates of several health concerns,7, 11-13

More specifically, studies have found that 41% of transgender people had attempted suicide at some point in their lives1 and that transgender women have one of the highest prevalences of HIV of any group.14 Survival sex work—or engagement in sex work in order to access basic necessities such as food and shelter—increases the risk for some. Transgender women, particularly those of color, have to contend with greater vulnerability to violence.3

Transgender people have been shown to have higher odds of depression and attempted suicide over non-transgender (cisgender) people.12,13 These data suggest the importance for providers to screen and treat those patients experiencing mental health challenges.

In addition, some transgender people may seek unauthorized (sometimes referred to as underground) care through the Internet, friends, and/or other nonmedical individuals in their social circle. They may take nonprescription and potentially dangerous hormones, or get silicone injections or have silicone implants to enhance their appearance. This can lead to a higher risk of illness and injury, further complicating health disparities7. For instance, sharing needles to inject silicone or hormones may place transgender people at risk for HIV and hepatitis C.

Consider having a conversation on the different types of medical care that a person uses, both from a health provider and possibly from a friend or other nonmedical people. Consider discussing possible options for safer ways to get what they are looking for in their health care.

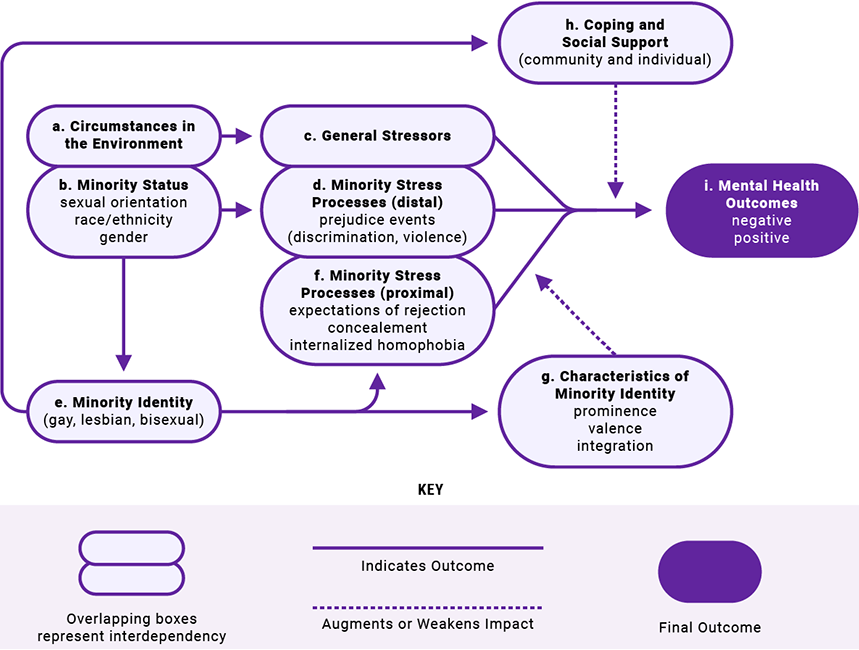

This figure illustrates how stigma and discrimination can impact health and lead to disparities and inequities in health27.

Minority Stress Process in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations

Health care organizations seeking to improve transgender patients’ experiences can implement several strategies to create a welcoming environment. These strategies involve all members of the care team, from front-desk staff to clinicians to administrators, and they are based on the principles of being welcoming, responsive, accountable, reliable, and respectful.

Tools for Effective Communication

One of the most important steps in creating a welcoming environment for transgender people (and all people) is to address patients using their preferred names and pronouns. For many reasons, this can be challenging in health care environments. Yet using the wrong name or pronoun can cause embarrassment and confusion. Imagine how a transgender woman would feel if a medical assistant called into the waiting room asking for “Mr. Donald Jones” rather than “Denise Jones.” To avoid such situations, here are a few suggested systems and practices that some health care teams have implemented:

- Ask about gender identity on registration forms. In addition to gender identity, include fields for listed sex at birth, preferred name, and pronouns. It may also be helpful to ask for names on insurance and government-issued identification documents, if different.

- Enter the information into the electronic health record (EHR) so that all staff have access to this information. This information will help staff to use proper pronouns, from the front desk staff to the provider’s office. If EHRs are not yet in place, consider using a name-alert sticker to flag patient charts.

- Never refer to a person as “it.”

- Try to avoid using gender terms or pronouns with new patients until this information is known, whether in-person or over the phone. For example:

- Instead of “How may I help you, sir?” ask “How may I help you?”

- Instead of “Mr. or Ms.” use the (preferred) first and last name.

- Instead of “He is here for his appointment,” say “The patient is here in the waiting room,” or “Dr. Reed’s 11:30 patient is here,” or “They are here for their appointment.”

- Ask patients how they would like to be addressed. When unsure about pronouns and names, it is acceptable to privately and politely ask, “I would like to be respectful. What name and pronouns would you like me to use?” Once a patient has given this information, staff should note it in the chart and use this name in all interactions. If a situation occurs where it is not possible to ask and pronouns must be used, choose the pronouns that most closely match the person’s gender expression or use “they/them.” See the box below for examples of pronouns that transgender people may use.

| Examples of Pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Pronouns | She | Her | Hers |

| Male Pronouns | He | Him | His |

| Non-binary Pronouns | Ze | Zim | Zirs |

| Non-binary Pronouns | Sie/Zie | Hir | Hirs |

- Apologize for mistakes. Sometimes mistakes happen, and simple apologies can go a long way. If a slip occurs, it is fine to say something like, “I apologize for using the wrong pronoun/name. I did not mean to disrespect you.”

- Consider practicing with colleagues and friends. Making changes to the way one addresses other people can be challenging. It can help to practice with colleagues and to post the Communication Strategies and Scripts—Best Practices sheet in accessible work spaces.

What To Do When a Patient’s Records Do Not Match

Health care staff are likely to encounter situations in which a transgender patient’s registration forms, records, insurance, and/or identity documents have different names and genders/sexes listed. It is important for staff members to ask for information without embarrassing or “outing” the patient. Some strategies for handling these situations include the following:

- Ask straightforward, polite questions to help solve the problem. For example, ask: “Could your chart be under a different name?” or “What is the name on your insurance?” Then cross-check identification by looking at date of birth and address. It may be best to ask these questions in a private setting. However, that may not always be possible. If in a public space, such as at a check-in desk, consider asking patients to write down their names.

- Avoid asking for a person’s “real” name. Patients may feel offended because these terms assume that their preferred names are not real.

Other Communication Tips

- Stay relaxed and make eye contact. Speak with transgender patients the same way you would with all patients.

- Avoid asking unnecessary questions. People are naturally curious about transgender people and their lives, which sometimes leads them to want to learn more and ask questions. However, like everyone else, most transgender people wish to keep their medical and personal lives private. Before asking a transgender person personal questions, first ask yourself, “Is my question necessary for their care or am I asking because of my own curiosity?” Reconsider if it is because of your own curiosity. Think instead, “What do I know? What do I need to know? How can I ask for the information I need in a sensitive way?”

- Do not gossip or joke about transgender people—patients and celebrities alike. Gossiping about someone’s transition or making fun of a person’s efforts to change their gender expression should not be tolerated.

- Only discuss a patient’s transgender status in a private setting, and only with those who need to know in order to provide appropriate and sensitive care.

- Continue to use the patient’s preferred name and pronouns, even when they are not present. This will help maintain respect for the patient and help other staff members learn the patient’s preferences.

- Encourage accountability in the workplace. Encourage colleagues to use the correct names and pronouns and point out when a comment could be perceived as insensitive. Creating a culture of accountability and respect requires everyone to work together.

Organizational Strategies for Creating a Patient-Centered Environment

Multiple strategies can help health care organizations create an inclusive, patient-centered, and welcoming health care environment for transgender people. Some suggested strategies are listed below. Resources to help organizations implement these strategies are listed in Additional Resources.

Policies and procedures

- Consider including “gender identity and expression” in nondiscrimination policies. Post these policies in visible places, such as on a website, in waiting rooms, on promotional materials, and/or on registration forms.

- Implement a policy that allows people to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity. Offer single-occupancy bathrooms that are designated for all genders.

- Consider actively seeking to hire transgender people.

- Create policies for both staff and patients with clear lines of referral for complaints and questions.

Training

- Many facilities that implement policies, such as those referenced above, find it beneficial to train managers so that they know and understand these policies and procedures. For those facilities that choose to implement training, it can be helpful to provide annual training on patient-centered care for transgender people for all staff, as well as training for new staff soon after they are hired.

Comprehensive services

- Consider offering a full range of services for transgender patients, including hormone treatment; HIV testing, prevention, and treatment; behavioral health care; support groups; and employment and housing services (if feasible). If not equipped to offer all of these services, consider maintaining an updated list of appropriate local and online referrals.

- A staff person could be appointed to be responsible for providing guidance, assisting with procedures, offering referrals, and fielding complaints.

Physical environment

- Consider including images of transgender people of various races and ethnicities in marketing and educational materials, such as on the organization’s website and in informational brochures. Visit the Get Materials section to download and order posters, palm cards, brochures, videos, and digital banners.

- Adding trans-friendly signage at the entrance to the facility and bathrooms (e.g., “All-Gender Restroom” sign) can help communicate a welcoming environment.

Community Engagement and Patient Feedback

- Some people find it helpful to employ transgender people as peer educators.

- A number of facilities partner with local lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community groups to sponsor or cohost events for National Transgender HIV Testing Day (April 18), Pride, and Transgender Day of Remembrance (November 20). Facilities that have chosen to partner for commemorating days have often found that doing so can create a sense of trust that is important for delivering patient-centered health care for transgender people.

| Best Practice | Example |

| When addressing new patients, avoid pronouns or gender terms like “sir” or “ma’am.” | “How may I help you today?” |

| When talking to coworkers about new patients, also avoid pronouns and gender terms. Or use gender-neutral words such as “they.” Never refer to someone as “it.” | “Your patient is here in the waiting room.” “They are here for their 3 o’clock appointment.” |

| If you are unsure about a patient’s preferred name or pronouns, ask politely and privately. | “What name and pronouns would you like us to use?” “I would like to be respectful—how would you like to be addressed?” |

| Ask respectfully about names if they do not match in your records. | “Could your chart be under another name?” “What is the name on your insurance?” |

| Ask only for information that is required. | Ask yourself, “What do I know? What do I need to know? How can I ask in a sensitive way?” |

| Did you make a mistake? Apologize. | “I apologize for using the wrong pronoun. I did not mean to disrespect you.” |

Common Definitions

Transgender people use many different terms to describe themselves and their communities. Common definitions and terms are listed below, but this vocabulary is not universal or static. Because the use of these terms changes over time and from one area to another, people may use or understand these words in a different way than what is defined below, or they may use other words to describe themselves and others. If a term that a patient uses is unclear or requires clarification, simply ask the patient what the term means in an open and respectful manner. People may also change the way they describe themselves over time. It is best to give all patients an opportunity to provide information on how they want to be recognized in a health care environment.

- Agender or non-binary: transgender or gender nonconforming person who identifies as neither male nor female or can be seen as a statement of not having a gender identity.

- Cisgender: Cisgender people are those whose gender identity and assigned sex at birth correspond (i.e., a person who is not transgender).

- Gender identity: A person’s internal sense of being a man/male, woman/female, both, neither, or another gender.

- Gender expression/role: The way a person acts, dresses, speaks, and behaves (i.e., feminine, masculine, androgynous). Gender expression does not necessarily correspond to listed sex at birth or gender identity.

- Gender nonconforming: Describes a gender expression that differs from a given society’s norms for males and females. A gender nonconforming person is not necessarily transgender.

- Genderqueer: A relatively new term, used by some individuals who do not identify as either male or female; or identify as both. Other terms include gender variant, gender expansive, gender fluid, and non-binary.

- Gender expansive: People who do not identify with traditional gender roles—masculine and feminine. People who describe themselves as gender expansive can identify in many different ways, such as a third gender, no gender, more than one gender, or a “fluid” gender.

- Latinx: Used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina.

- Transgender: Transgender people are those whose gender identity and assigned sex at birth do not correspond. Transgender is also used as an umbrella term to include gender identities outside of male and female. Transgender is sometimes abbreviated as trans. Some of the terms used to describe populations within the transgender community are:

- Transgender/trans man; female-to-male (FTM): People whose assigned sex at birth is female and whose gender identity is male may use these terms to describe themselves. Some will simply use the term man.

- Transgender/trans woman; male-to-female (MTF): People whose assigned sex at birth is male and whose gender identity is female may use these terms to describe themselves. Some will simply use the term woman.

- Transsexual: The term transsexual is sometimes used in medical literature to describe those who have transitioned through medical interventions. Some transgender people prefer to describe themselves as transsexual; however, many consider the term to be outdated or derogatory. We advise that providers avoid this term, unless a patient explicitly requests to be referred to as transsexual.

- Transition process: For transgender people, this refers to the process of coming to recognize, accept, and express one’s gender identity. Most often, this refers to the period when a person makes social, legal, and/or medical changes, such as changing their clothing, name, or sex/gender designation on legal documents or using medical interventions such as hormone therapy or surgeries.

- Sexual orientation: This refers to how people describe their emotional and sexual attraction to others. Sexual orientation is distinct from gender identity. Transgender people can be any sexual orientation (gay, lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual/straight, no label at all, or some other self-described label). Language is always changing and subjective. The table below shows terms that should be avoided and terms that should be used instead. It is important to remember that whenever possible, it is best to ask.

| Stop! Avoid these terms! Some terms are considered offensive or outdated.

Avoid using these: |

Go! Use these instead! Some acceptable terms are: |

|---|---|

| Transgendered | Transgender or trans |

| He-she, she-male, it | He, she, they (or ask) |

| Transvestite, transsexual, tranny* | Transgender, or however that person describes themselves |

*Although often considered derogatory, some transgender people use these terms in a positive way to describe themselves or others.

- Grant J, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. https://dataspace.princeton.edu/jspui/handle/88435/dsp014j03d232pexternal icon. Accessed August 31, 2016.

- Human Rights Campaign. Addressing anti-transgender violence [Internet]. Washington, DC: Human Rights Campaign; 2015. http://hrc-assets.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com//files/assets/resources/HRC-AntiTransgenderViolence-0519.pdfpdf iconexternal icon . Accessed August 31, 2016.

- Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Gamarel KE, Hughto JM, Pardee DJ, Keo-Meier CL. Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among U.S. female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):324-332. PubMed abstractexternal icon.

- Xavier J, Honnold JA, Bradford J. The health, health-related needs, and lifecourse experiences of transgender Virginians. Richmond, VA: Virginia HIV Planning Committee and Virginia Department of Health; 2007. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/10/2016/01/THISFINALREPORTVol1.pdfpdf iconexternal icon

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TN. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2016. http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf?_sm_au_=iVV5Zj8QFq5k5M06pdf iconexternal icon.

- Meerwijk, EL, Sevelius, JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. AJPH Transgender Health. 2017;107(2):e1-e8. PubMed abstractexternal icon.

- National Academy of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

- Pew Research Center. A survey of LGBT Americans. 2013. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americansexternal icon. Accessed January 7, 2020.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS%20Full%20Report%20-%20FINAL%201.6.17.pdfpdf iconexternal icon.

- Taylor M. I was arrested for just being who I am. American Civil Liberties Union Blog. November 10, 2015. https://www.aclu.org/blog/speak-freely/i-was-arrested-just-being-who-i-amexternal icon. Accessed August 31, 2016.

- Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25external icon.

- Dejun S, Irwin J, Fisher C, et al. Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: a comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health. 2016;1(1).

- Brown, GR, Jones, KT. Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the Veterans Health Administration: a case–control study. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2).

- Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al.; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008; 12(1):1-17. PubMed abstractexternal icon.

- Meyer, IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674external icon.

Transgender is used here as an umbrella term to describe people who have a gender identity that is different from their sex listed on their birth certificate. Gender identity is on a spectrum. It is important to keep in mind that although some transgender people prefer the binary classification of men or women, many reject it. Instead, they may have other identities, such as non-binary, gender expansive, genderqueer, or trans-feminine/trans-masculine. These terms emphasize a broader view of gender and may provide a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be a transgender person.

A note regarding HIV research published in academic journals: An important consideration in research with transgender people is the challenge to accurately classify transgender women for surveillance/research purposes. Not all jurisdictions collect data on gender identity that include transgender people, and some researchers may use older methods that can misclassify transgender women as men who have sex with men. This can also happen as some transgender people may not identify themselves as transgender in health care settings due to fear of discrimination or previous negative experiences. This mix of limitations can result in over- or under-estimating the number of transgender people. As such, it is important to consider methodologies when interpreting data and surveillance findings. As the field is developing newer and more precise ways to identify transgender identity for research and surveillance purposes, it is important to consider methodological approaches, particularly for studies that include both men who have sex with men and transgender women. The most accurate method uses a two-step process, including two questions: “What is your current gender?” AND “What sex were you listed as at birth?” The large majority of studies cited in this document use a two-step process, however one is a meta-analysis and likely includes studies with a one-step process to determine gender identity. For more information about using a two-step process, please refer to the section Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.

1 James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. hJames SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. https://calculators.io/national-transgender-discrimination-survey/external icon.

2 Clark H, Babu AS, Wiewel EW, Opoku J, Crepaz N. Diagnosed HIV infection in transgender adults and adolescents: results from the National HIV Surveillance System, 2009-2014. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:2774–2783. PubMed abstractexternal icon.

3 Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa DH, Sipe TA. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2018:e1-e8. PubMed abstract external icon.