ARDI Methods

back to: Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) Home

The Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application provides estimates of alcohol-related harms including alcohol-attributable deaths (AAD), years of potential life lost (YPLL), and alcohol-attributable fractions (AAF).

Both AAD and YPLL are calculated using population estimates of the total proportion of deaths for various causes that are attributable to alcohol use. These proportions, called AAFs, are either measured directly or calculated indirectly using current scientific literature. The causes of death calculated indirectly, using population attributable fraction methodology, are still directly related to alcohol use but the calculations involve several types of information.

Alcohol-Attributable Fractions (AAF)

100% Alcohol-Attributable Conditions

Certain causes of death are, by definition, caused by alcohol consumption. These deaths are classified as being 100% alcohol-attributable and are reported in ARDI as having an AAF of 1.00. The following 13 chronic causes of death are listed as 100% alcohol-attributable in ARDI: alcoholic psychosis, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol polyneuropathy, degeneration of the nervous system due to alcohol use, alcoholic myopathy, alcohol cardiomyopathy, alcoholic gastritis, alcoholic liver disease, alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis, alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis, fetal alcohol syndrome, and fetus and newborn issues caused by maternal alcohol use. Two acute causes of death are 100% alcohol-attributable: alcohol poisoning and suicide by and exposure to alcohol.

Directly Measured AAF

In contrast, the AAF for most of the acute causes of death (e.g., injuries) are assessed using direct estimates of AAF. Most of the direct AAF estimates for acute causes of death are based on a meta-analysis,2 except for deaths due to motor vehicle traffic crashes and other road vehicle crashes. Researchers systematically reviewed studies that directly measured the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of people who had died of fatal non-traffic injuries. In this study, injuries were generally defined as having been alcohol-attributable if the decedent had a BAC ≥ 0.10 g/dL at the time of death. Seven causes of injury deaths (aspiration, child maltreatment, fall injuries, homicide, hypothermia, occupational and machine injuries, and other road vehicle crashes) had limited data, so these AAFs are based more broadly on alcohol intoxication. The AAFs for deaths from motor vehicle traffic crashes came from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), where the AAFs are based on the proportion of deaths from motor vehicle traffic crashes where either the driver or the non-occupant had a BAC level at or above 80 mg/dL, or 0.08 g/dL, by state, sex and age group. FARS national data were also used for calculating the other road vehicle crashes AAFs.

Indirectly Measured AAF

For some causes of death, particularly chronic causes, ARDI calculates indirect estimates of AAF, using population attributable fraction methodology. These causes of death are still directly related to alcohol use, but the calculations involve several types of information. These calculations use pooled risk estimates obtained from large, systematic reviews of the scientific literature, known as meta-analyses, on the relationship between alcohol and various causes as well as data on the prevalence of alcohol consumption at specific levels (e.g., more than one drink per day on average). Various sources were used to determine the pooled risk estimates used in ARDI for calculating the AAFs. The conditions and sources are listed with the cut-points used for defining levels of average daily alcohol consumption (see below).

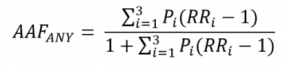

Indirect estimates of AAF for any level of alcohol consumption are calculated in ARDI using the following formula:

which is equivalent to:

Where:

P1 is the prevalence of low volume alcohol consumption.

P2 is the prevalence of medium volume alcohol consumption.

P3 is the prevalence of high volume alcohol consumption.

RR1 is the relative risk low volume alcohol consumption.

RR2 is the relative risk medium volume alcohol consumption.

RR3 is the relative risk high volume alcohol consumption.

The prevalence of alcohol consumption is calculated at a specified level of average daily consumption within a given year, and relative risk is the likelihood of death from a particular cause at a specified level of average daily alcohol consumption. In accordance with the methods used by D. English when evaluating the relationship between medium and high average daily alcohol use (see below for definitions) and deaths from various causes, the risk estimates for these consumption levels were divided by the risk estimate for low average daily alcohol consumption, thus making people in the low average daily consumption group the reference population rather than abstainers.3

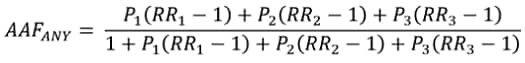

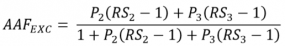

For excessive alcohol consumption, ARDI defines

and

as rescaled relative risks for medium and high volume alcohol consumption, respectively, using low volume alcohol consumption as the comparison group. ARDI, therefore, uses the following formula to calculate the AAF for excessive alcohol consumption:

Where all notations have been defined above.

For acute pancreatitis, data were not available to determine the relative risk at the various levels of alcohol consumption;4 therefore, the rescaling procedure was not used to calculate the AAF for excessive alcohol consumption for acute pancreatitis. The AAF for acute pancreatitis for excessive consumption was calculated using the single relative risk estimate for both the medium and high average daily alcohol consumption levels.

Prevalence Data

When calculating indirect AAF, ARDI uses the prevalence or the proportion of U.S. adults aged 20 years and older (stratified by sex) who reported average daily alcohol consumption at various levels. This information is obtained from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). The BRFSS data in ARDI are selected using the same years as both the death data and the life expectancy data used in the application. For example, if the most recent death data were for 2020–2021, then 2020–2021 BRFSS data were used as the basis for calculating the prevalence of average daily alcohol consumption.

Calculating Average Daily Alcohol Consumption

To better estimate average daily alcohol consumption, prior to the release of the 2015–2019 data in 2022, ARDI used a survey-based adjustment procedure called indexing to include self-reported information on binge drinking episodes into the calculation of average daily alcohol consumption.5 Starting with the ARDI release in 2022 (with 2015–2019 data), the ARDI application adjusts the prevalence of low, medium, and high average daily alcohol consumption to account for the underreporting of self-reported alcohol consumption in the BRFSS using per capita alcohol sales data. Individual-level average daily alcohol consumption estimates from the BRFSS are adjusted using a correction factor so that overall average daily consumption reaches 73% of national per capita sales.6 The 73% level was selected to equate with the coverage of per capita sales (based on alcohol sales data from the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System) that is achieved in epidemiological cohort studies used to derive condition-specific relative risk estimates.7,8 After adjusting the average daily alcohol consumption estimates, the weighted prevalence of low, medium, and high average daily alcohol consumption was calculated for men and women.

The low, medium, and high levels of the average number of drinks consumed per day (adjusted to 73% of per capita alcohol sales) are defined by cut-points specified in the meta-analyses used to obtain risk estimates for a given cause of death. These cut-points were typically reported as grams of alcohol per day, and then converted into drinks per day, using a 14 gram per drink conversion factor. The following cut-points were used for causes for which the categorical relative risk estimates were derived from continuous risk distributions presented by the authors of various studies, or for which varying relative risks were not presented by level of alcohol consumed. The relative risks correspond to the median within the low, medium, and high average daily alcohol consumption categories.

Standardized cut-points for assessing the prevalence of alcohol consumption.

| Alcohol Consumption | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

|

| Low | >0-≤28 | >0-≤2 | >0-≤14 | >0-≤1 |

| Medium | >28-≤56 | >2-≤4 | >14-≤28 | >1-≤2 |

| High | >56 | >4 | >28 | >2 |

*Categorical relative risks were derived from continuous risk distributions

The causes for which these cut-points were applied include the following:

-

- Acute pancreatitis.4

- Atrial fibrillation.9

- Cancers.10*

- Hypertension.11

- Infant deaths due to low birth weight, pre-term birth, and small for gestational age.12†

- Ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.13

- Pneumonia.14‡

- Unprovoked seizures, epilepsy, or seizure disorder.15

Categorical relative risks were derived from continuous risk distributions for each of these conditions except for acute pancreatitis, in which varying relative risks were not presented by level of alcohol consumed.4

*Alcohol-related deaths from esophageal cancer were calculated for the proportion of esophageal deaths due to squamous cell carcinoma only (25.6% among men and 52.7% among women), based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results in 17 states (SEER17). Other esophageal cancer deaths are not related to alcohol use and not included in ARDI. Alcohol-related deaths from stomach and pancreatic cancer were calculated among those consuming high levels of alcohol only.

† To estimate alcohol-attributable infant deaths due to low birth weight, pre-term birth, and small for gestational age, the prevalence of average daily alcohol consumption was calculated among women aged 18 to 44 years only because the alcohol consumption by other populations (e.g., males or older women) is not pertinent, and there is no available data source for calculating the prevalence of average daily alcohol consumption among only pregnant women on a state-specific basis. The prevalence estimates for women aged 18 to 44 years by level of consumption were applied to both males and females in the AAF formula in order to assess deaths by both infant boys and girls.

‡ For estimating alcohol-attributable deaths from pneumonia, the prevalence of average daily alcohol consumption was calculated among people aged 20 to 64 years only due to the high number of deaths from pneumonia among people aged 65 years and older that are not alcohol-related.

The following cut-points were used for causes for which the relative risk estimates were drawn from either Corrao16 or Corrao17:

| Alcohol Consumption | Men and Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

|

| Low | ≥1.4-<25 | ≥0.1-<1.8 |

| Medium | ≥25-<50 | ≥1.8-<3.6 |

| High | ≥50 | ≥3.6 |

The causes for which these cut-points were applied include:

- Chronic hepatitis.16

- Chronic pancreatitis.17

The following cut-points were used for gallbladder disease, for which the relative risk estimates were drawn from English3:

| Alcohol Consumption | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

|

| Low | ≥2.8-<40.6 | ≥0.2-<2.9 | ≥2.9-<19.6 | ≥0.2-<1.4 |

| Medium | ≥40.6-<60.2 | ≥2.9-<4.3 | ≥19.6-<40.6 | ≥1.4-<2.9 |

| High | ≥60.2 | ≥4.3 | ≥40.6 | ≥2.9 |

The following cut-points were used for coronary heart disease, for which the relative risk estimates were drawn from Zhao18:

| Alcohol Consumption | Men and Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Grams | Average Drinks/Day

(14g/drink) |

|

| Low | 1.3-<25 | 0.09-<1.8 |

| Medium | 25-<45 | 1.8-<3.2 |

| High* | ≥45 | ≥3.2 |

*High volume and higher volume categories from Zhao18 were combined into a single category for the purpose of ARDI

Based on the above cut-points, excessive alcohol use was defined in the ARDI application as medium or high average daily alcohol consumption because these consumption levels generally exceeded the average daily consumption levels that are used to define heavy drinking (more than 1 drink/day on average for women; more than 2 drinks/day on average for men).

Data Sources for Total Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL)

Total Deaths Data Set

To calculate alcohol-attributable deaths (AAD), the AAFs for a specific condition are multiplied by the number of deaths in a given age category. The death data were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System managed by the National Center for Health Statistics. Deaths were coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). See Alcohol Related ICD Codes. In contrast to deaths with ICD-10 codes indicating known intent (either homicide or suicide), for some acute causes of death (i.e., drowning, falls, fire injuries, firearm injuries, alcohol poisoning, poisonings (not alcohol)), ICD-10 codes for deaths of undetermined intent are included in the mechanism of death condition.

The death data were stratified by age and sex using standard 5-year age groupings. In general, ARDI assesses chronic causes of death starting at age 20 and acute causes of death starting at age 15. Deaths from pneumonia were included in ARDI for people aged 20 to 64 years only due to the high number of deaths from pneumonia among people aged 65 years and older that are not alcohol-related and the lack of relative risks that differ by age. Similarly, deaths from falls were included in ARDI for people aged 15 to 69 years only due to the high number of deaths from falls among persons aged 70 years and older that are not alcohol-related and the lack of AAFs that differ by age. In addition, death data were also included in ARDI on people who were younger than 15 years at the time of death if they died from alcohol-related causes that specifically affect children. These include fetal alcohol syndrome; fetus and newborn affected by maternal use of alcohol; child maltreatment; and infant deaths due to low birth weight, pre-term birth, and small for gestational age. Deaths due to motor vehicle traffic crashes among people younger than 15 years were also included in the system, because data on alcohol involvement in these deaths are available through FARS.

To protect confidentiality, in the reports of AADs for each state and the District of Columbia, data are suppressed in cells with an estimate of fewer than 10 deaths or in which presenting data would provide information to derive the estimate for another cell that has fewer than 10 deaths.

Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL)

YPLL are calculated by multiplying age- and sex- specific average annual estimates of alcohol-attributable deaths due to the 58 conditions included in the ARDI application by age- and sex-specific average annual estimates of years of life remaining from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Because YPLL is based on the age at death, the YPLL for a particular cause of death are directly related to the age distribution of people who typically die of that condition. As a result, YPLL generally tends to be higher for causes of death that disproportionately affect youth and young adults (e.g., motor vehicle traffic deaths) and lower for causes that primarily affect older adults (e.g., coronary heart disease).

Limitations

ARDI may underestimate the actual number of alcohol-related deaths and YPLL in the United States for several reasons. First, BRFSS prevalence estimates are based on alcohol consumption during the past 30 days. As a result, former drinkers, who may have discontinued drinking because of health problems, are not included in the calculation of AAFs for partially alcohol-attributable causes of death. In the AAF formulas used in ARDI, it is assumed that former drinkers have the same relative risk as the comparison group (that is, lifetime abstainers when calculating the AAF for any volume of alcohol consumption, and low volume drinkers when calculating the AAF for excessive alcohol consumption). Second, ARDI does not include estimates of alcohol-attributable deaths for several causes (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and hepatitis C) for which alcohol is an important risk factor, but where a suitable pooled risk estimate was not available. Third, ARDI exclusively uses the underlying cause of death to identify alcohol-related causes of death and does not consider contributing causes of death that may also be alcohol-related. Finally, age-specific estimates of AAF were only available for motor vehicle traffic deaths even though alcohol involvement is known to vary by age. In addition, because of the high rates of death from pneumonia and falls among older people that are not related to alcohol, and the inability to identify different estimates of AAF for older people compared with younger people, deaths included in ARDI for these conditions were limited to people aged 64 years and younger for pneumonia and aged 69 years and younger for falls. This results in an underestimation of alcohol-related deaths from pneumonia and falls among older adults and overall.

Scientific Work Group

Building on the work of an ARDI Scientific Work Group in 2002, the CDC convened a Scientific Work Group in 2016 including experts on alcohol and health from academia, government and private sector to assist with the ARDI scientific update.

The 2016 Work Group was tasked with reviewing a proposed list of alcohol-attributable conditions and the scientific literature identified for updating the cause-specific AAFs, with a focus on meta-analyses, when available. Members of the Work Group provided valuable input on the literature identified for updating the AAFs, ensuring the use of the best available scientific evidence on the role of alcohol and specific causes of death included in the ARDI application. The Work Group also assisted with updating the ICD-10 codes used for defining the conditions in ARDI.

- Parrish KM, Dufour MC, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Average daily alcohol consumption during adult life among decedents with and without cirrhosis: the 1986 National Mortality Followback Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(4):450-456.

- Alpert HR, Slater ME, Yoon YH, Chen CM, Winstanley N, Esser MB. Alcohol consumption and 15 causes of fatal injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63:286–300.

- English DR, Holman CDJ, Milner K, et al. The Quantification of Drug Caused Morbidity and Mortality in Australia, 1995 edition. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health; 1995.

- Alsamarrai A, Das S L, Windsor J A, Petrov, MS. Factors that affect risk for pancreatic disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1635–1644.

- Stahre M, Naimi T, Brewer R, Holt J. Measuring average alcohol consumption: the impact of including binge drinks in quantity-frequency calculations. Addiction. 2006;101:711–1718.

- Esser MB, Sherk A, Subbaraman MS, et al. Improving estimates of alcohol-attributable deaths in the United States: impact of adjusting for the underreporting of alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2022;83:134–144.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Epidemiologic Data Directory. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2022.

- Stockwell T, Zhao J, Sherk A, Rehm J, Shield K, Naimi T. Underestimation of alcohol consumption in cohort studies and implications for alcohol’s contribution to the global burden of disease. Addiction. 2018;113:2245–2249.

- Samokhvalov AV, Irving HM, Rehm, J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010a;7;706–712.

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, Pelucchi C. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:580–593.

- Taylor B, Irving HM, Baliunas D, Roerecke M, Patra J, Mohapatra S, Rehm J. Alcohol and hypertension: gender differences in dose–response relationships determined through systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction. 2009;104;1981–1990.

- Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VW, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age (SGA)-a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG. 2011;118:1411–1421.

- Patra J, Taylor B, Irving H, Roerecke M, Baliunas D, Mohapatra S, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption and the risk of morbidity and mortality for different stroke types-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010:10:258.

- Samokhvalov AV, Irving HM, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2010b;138:1789–1795.

- Samokhvalov AV, Irving H, Mohapatra S, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption, unprovoked seizures, and epilepsy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epilepsia. 2010c;51:1177–1184.

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Arico S. Exploring the dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of several alcohol-related conditions: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 1999;94:1551–1573.

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38:613–619.

- Zhao J, Stockwell T, Roemer A, Naimi T, Chikritzhs T. Alcohol consumption and mortality from coronary heart disease: An updated meta-analysis of cohort studies. Journal Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:375–386.