Understanding Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in Kazakhstan

Between 2000 and 2013, the Zhambyl region of Kazakhstan reported the second highest number of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) illnesses in people, out of all the regions in the country. Although outbreaks of CCHF happen regularly in Kazakhstan, public health officials wanted to understand why this particular region had a higher number of cases.

A local resident inspects his herd of sheep.

People can get CCHF from ticks or contact with infected animal blood. Livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep can become infected with CCHF—although many have mild or no symptoms—and are often the starting point for outbreaks in people. The virus that causes CCHF can also spread from person to person through infected body fluids. There is no cure or vaccine for CCHF, and it can kill up to half of the people it infects. About 80% of people infected with CCHF will not have symptoms, so the spread of the disease may go unnoticed in a population.

Combining study methods to maximize results

As part of CDC’s global disease detection work, CDC staff worked with Zhambyl public health and veterinary officials to design an innovative, two-pronged approach to learn about the spread of CCHF in Zhambyl.

Residents randomly selected for participation in the serosurvey line up outside the local health department to get their blood drawn by a nurse from the Zhambyl regional health department.

First, CDC staff and local officials tested blood samples to discover how many people and livestock in the region had been exposed to CCHF. Next, they deployed a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey to measure knowledge about CCHF in the community, especially among those most at risk: people who interact with livestock.

A previous CCHF serosurvey (testing blood in a population of people or animals) in the Zhambyl region was conducted over 45 years ago, and a KAP study had never been done before. Combining these two approaches would not only help establish where the virus was circulating and where it was likely to spread, but also uncover which behaviors and practices might be increasing the risk of spreading this disease.

One Health collaboration in the field

Teams doing the surveys included members from the Zhambyl region Department for Public Health Protection, Health Care Department, and Department of Veterinary Control and Surveillance. Reflecting a One Health approach, team members came from different areas and included epidemiologists, a veterinarian, nurses, and entomologists. Staff from CDC headquarters in Atlanta and CDC-Kazakhstan developed the study protocol, trained the teams on data collection methods, and oversaw the data collection.

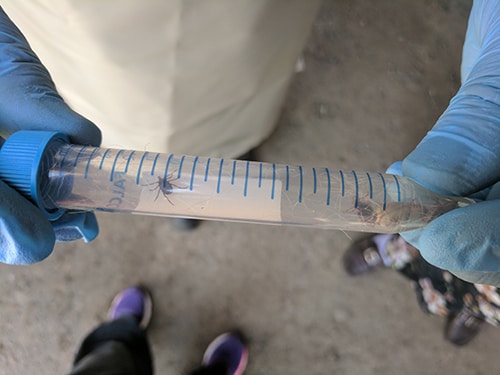

The teams visited 30 villages, sampled blood from people, sheep, and cows, and tested for evidence of past CCHF infection. They also inspected the animals and collected ticks for testing. As part of the KAP study, the teams also asked one member of each household questions to determine their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors about CCHF and its risk factors, such as being in close contact with animals and their blood and tick bites.

Embracing a One Health approach

An entomologist from the Zhambyl regional health department displays the ticks he collected from livestock for testing.

Of the nearly 1,000 people tested for CCHF, five had been infected with CCHF within the previous four months, and 14 people had been infected within the previous five or more years. The teams learned that all 14 of these people had performed some type of high-risk activity such as shearing wool, milking, slaughtering, or assisting with animal births.

Several of the CCHF cases in people were from villages where this hemorrhagic fever had never been officially reported, showing that the virus was circulating in more places than public health officials originally thought.

Only 20% of the people interviewed for the KAP study reported wearing any kind of personal protective equipment such as boots, gloves, gowns, or a face shield when slaughtering animals, which is a high-risk activity for contracting CCHF. Although the KAP also found that many community members were very aware of CCHF, there was less knowledge about prevention methods. Among those who had heard of CCHF, most knew that ticks could spread the disease but few knew the role animals could play, and some were confused about how the disease spreads from person to person.

Of the more than 1,000 sheep and cows inspected for ticks during the study, 1.2% carried a tick that tested positive for CCHF. Over 97% of the ticks collected from the animals were of the Ixodidae family, which can carry the CCHF virus.

While tick treatment was reported in the KAP to be common for animals, only Ivermectin was found to be effective based on which animals ticks were found on, suggesting that ticks in the area may have become resistant to certain insecticides.

Children ride a donkey home at the end of the day in the study region of Zhambyl Oblast.

The study helped to identify gaps in knowledge about CCHF. Officials are planning more prevention campaigns in the region to raise awareness of CCHF and teach people ways to reduce their risk when handling livestock. They also plan to increase testing of ticks, people, and livestock for additional tick-borne viruses and are interested in learning more about insecticide resistance in the region.

By using a One Health approach to address CCHF at the human-animal-environment interface, Kazakhstan hopes to improve its ability to detect, prevent, and respond to zoonotic diseases such as CCHF.