The Importance of Knowing Your Data: Diagnosis Codes Set Off Red Flags for Polio Among Older U.S. Residents

After the July 2022 diagnosis of a polio case in New York, syndromic surveillance seemed an obvious strategy to monitor for additional cases. Even though physicians were primed to look for polio symptoms and state and federal reporting systems for polio are well established, syndromic surveillance complements these efforts with additional insights from data already being collected by public health jurisdictions.

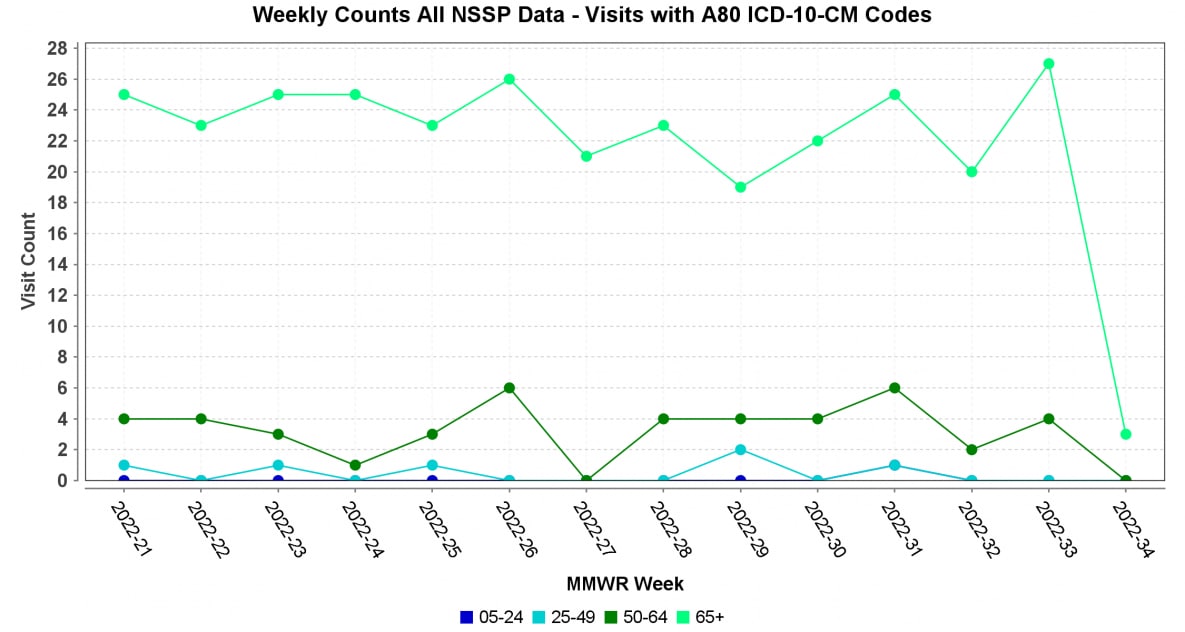

For emerging topics of interest like this—a potential resurgence of polio—our immediate queries to quickly respond tend to rely heavily on discharge diagnosis codes, like ICD-10-CM “A80 Acute poliomyelitis.” But simply searching for this code may raise unnecessary alarms and red flags. A search of A80 codes across NSSP data yields a weekly average of 26 visits over the last 90 days. So, in just 90 days, our system shows 360 visits with diagnosed ACUTE POLIO.

In fact, weekly visit counts with this code persist in our data all the way back to the ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM transition in 2015.

This is an extreme example of why we should not be too quick to react to red flags but should investigate further. Looking at these visits, we see them largely concentrated in the older age groups and in specific HHS regions (although all age groups and HHS regions have at least a few). Using text analysis tools, we see a high frequency of A80.9 Acute poliomyelitis, unspecified, coupled with terms like QUADRIPLEGIA, MUSCLE, REDUCED, MOBILITY, WEAKNESS, and FALL.

In this scenario, without further analysis, public health practitioners could be quick to believe that active polio is being diagnosed, when a history of childhood polio is being noted.

Why does this matter?

Analysts who know their community demographics and their surveillance data are in the best position to identify trends, spot anomalies, and form conclusions well-grounded in science.

Raw syndromic surveillance data—gathered directly from the source—are messy and require thoughtful use. A simplistic analysis can be misleading. Data need to be analyzed, checked, and rechecked.