Logger and Logging Supervisor Killed by Uprooted Tree

FACE 00-AK-024

Release Date: November 1, 2001

SUMMARY

An uprooted tree struck and killed a 34-year-old logging supervisor and a 33-year-old logger (the victims). The victims were part of a six-man crew using a crane to move cut timber from a slope to a road. The mobile crane, known as a “yarder,” was located on the road above the slope. It was anchored by a single guyline to an uncut tree on the hillside above the road. At the time of the incident, the yarder was attempting to pull a set of logs up the slope. During two previous attempts or “turns,” the logs had become hung-up on a stump. The two victims were standing near the yarder when a third “turn” was started. The logs hung-up again. The tree that was anchoring the yarder uprooted and fell toward the yarder.

A co-worker working on the slope below the road (the witness) saw the tree fall toward the yarder. He yelled to a co-worker to radio for help and climbed up the slope to the road where other workers met him. Both victims were found under the uprooted tree. CPR was performed but stopped when there was no detectable response. Alaska State Troopers were notified and the bodies recovered. The victims were pronounced dead at the scene.

Based on the findings of the investigation, to prevent similar occurrences, employers should:

- Ensure that all crewmembers are capable of recognizing hazardous conditions and are authorized to stop work so that work procedures can be modified in accordance with safe logging and timber harvesting methods.

- Ensure that all skylines and guylines are anchored to stumps;

- Ensure that all personnel involved in rigging of cable yarding systems are trained in selecting and rigging anchor stumps;

INTRODUCTION

At approximately 10:30 A.M. on July 31, 2000, a 34-year-old male logging supervisor (Victim #1) and a 33-year-old male logger (Victim #2) were fatally injured when a tree, used as a guyline anchor, uprooted and struck them. On July 31, 2000, Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development (AKDOLWD) notified the Alaska Division of Public Health, Section of Epidemiology. An investigation involving an Injury Prevention Specialist for the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Section of Epidemiology ensued on the same day. The incident was reviewed with AKDOLWD officials. AKDOLWD, Alaska State Troopers, and Medical Examiner reports were requested. An inspection of the site was completed on August 1, 2000.

The company involved in this incident was a privately owned logging operation contracted to fell and harvest marked stands of timber. The company has been in business since 1967 and currently employed 200 workers at two operating locations in Alaska. Victim #1 had worked for the company since 1984 with a few intermittent breaks. He was initially hired as a carpenter’s assistant and had worked in many logging occupations including chokersetter [1] and chaser [2] during his tenure with the company. At the time of the incident, he was employed as one of three logging supervisors (siderods). Victim #2 had 5-7 years experience as a chaser and chokesetter. He had also worked as a chase supervisor (chase rod) for other operations.

The company had a written safety and health plan. At the time of hire, employees received training that included orientation to company safety and health policies and practices. Employees were required to have current CPR and first aid cards and were provided training for certification, if necessary. In addition, individual skills and knowledge were assessed by a siderod before an employee was given an assignment. Intermittent observations were made while working in their assigned areas to provide recommendations and corrective actions. Safety meetings were held weekly.

INVESTIGATION

The incident occurred in southeast Alaska, approximately 8 miles from the main camp and 25 miles from the nearest town. The land was privately owned where the logging company was contracted to cut and harvest timber. Workers traveled to worksites by truck. Each truck was equipped with a radio. Some individual workers, such as timber cutters, carried two-way radios. Each worker was required to use personal protective equipment including, but not limited to, hard hat, gloves, and chalked boots.

The primary type of timber harvesting undertaken by the logging operation was clear-cut. The stands of timber were marked for felling or as “no-cut” areas. The terrain varied in slope, altitude, and ground condition. Roads used to access the stands were flat to moderate in grade and consisted of crushed rock and dirt. The incident site was on a road above an area of cut timber. The road had an approximate 10% grade at the incident site and was backcut into the hillside. The hillside above and below the road at the incident site had a 15- to 30-degree slope. Ground conditions were composed of light to moderate brush and slash with occasional areas of heavier growth; unharvested logs and numerous stumps were present on the lower slope. The day prior to the incident, the weather was rainy, which varied from moderate to heavy. At the time of the site inspection, slopes above and below the road appeared moderately saturated with water. Many areas adjacent to the road had visible run-off and puddling.

Sections of the road were used as landings [3] for yarding [4] activities on the adjacent slope (below the road). Each new yarding/landing site was selected by the siderod after completion of a site survey. Selection was based on road condition, road grade (dictating the amount of bracing necessary to level the yarder), the line of vision for observation of rigging crew and the turn [5], and suitable guyline anchors.

The company used a cable yarding system to partially lift and/or drag (skid) logs from their felled location to a landing area. The system was made up of a single cable that was drawn from a crane, through two blocks, and back to the crane. The layout was usually triangular in shape, with the crane was the apex, and the mainline and haulback line composing the sides of the triangle (Figure 1). These lines were of relatively equal length to equalize the stress placed on them. The base of these triangular logging systems was typically shorter than the sides. The system required a minimum of three anchors: two for the lines and one for the yarder. Stumps used for anchorage were selected for their ability to withstand stresses or pull of the yarding lines. Secure anchors are essential in any arrangement to ensure that the stresses on the lines and boom are shared. In this arrangement, the boom of the crane was supported by a single guyline. This line also needed to be positioned to counter the force from the mainline and haulback line.

The logs (felled timber) were attached to the mainline line by a choker and skidded to the landing. A yarding engineer alternately applied and released a brake on the mainline drum and the haulback drum to move the choker up and down the slope. Some partial lift, to move around a hang-up, could be accomplished by drawing the slack out of the lines. This was done sparingly due to the additional stress on the lines and the loss of braking efficiency. For the most part, logs were dragged along the ground; consequently, hang-ups often occurred.

The company used a mobile swing yarder (Figure 2). The unit has two sections. The bottom section is a crawler (tracked) base. The upper section of the yarder consists of an operator compartment, a lattice boom crane, and a counterweight on a turntable mount (verses a fixed mount), which allows the upper section to pivot or “swing” 360 degrees on its base. The yarder had been in-service for 6-8 weeks before the incident. While the yarder was not used continuously, it incurred heavy use during yarding periods. Maintenance and repair normally expected for this type of equipment were reported in company records.

The two victims were part of a six-man crew assigned to land and yard felled timber. Besides the victims, the crew included a hooktender [6], a rigging slinger [7], a shovel operator, and a yarder engineer. Two days prior to the incident, the crew moved the yarder approximately 50 feet along the road to the incident site. This road site was selected for its flatter grade, which would require less bracing. Anchor selection was not done. The tracks of the yarder were blocked to level and brace the unit. Work at the site was stopped and not resumed until the day of incident.

On the day of the incident, as part of their normal duties to ready the cable system, a crewmember selected the cable and guyline anchors. Normally, this is a duty of the hooktender, however the company rotated this duty between the hooktender, the rigging slinger, and the yarder engineer. Stumps had been consistently used to anchor the cable at all previous sites. However, the stand of trees on the hillside above the road was designated as a “no cut” contingency unit by the landowner and scheduled for harvesting at another time (possibly one or two years later). No stumps either on the edge or within the “no cut” unit were in position to anchor the boom of the yarder. An uncut tree within the “no cut” unit, approximately 50 feet uphill from the yarder, was selected to anchor the boom. The tree was approximately 125 feet tall and 20-22 inches in diameter. The crew stated that uncut trees were rarely used. Except for the single guyline connected to the yarder, no other lines were attached to the tree. Both the tree and the stumps appeared to be notched properly to prevent movement of the line along the trunk of the tree.

Prior to the start of the yarding and landing activities, a company mechanic was called to adjust the friction brakes on the yarder. As described by the crew, turns seemed to remain hung-up (as they were pulled up the slope) more often, and the brake adjustment would help increase the force to move over stumps and other obstacles. The crew then worked 3-3½ hours setting and landing turns. At approximately 10:30 A.M., the hooktender and rigging slinger were working about 400 feet down the slope. They had initiated a turn (consisting of two logs) twice but were stopped both times by a stump that hung-up the logs. The rigging slinger (the witness) saw the victims standing near the right side of the yarder; the landing area was on the left side. They were looking down the slope as the witness initiated a third turn. It was speculated that the victims were watching to determine if another brake adjustment needed to be done or if the landing/yarding site needed to be moved. The witness saw the line go slack and then saw the tree fall toward the right side of the yarder.

As the witness climbed up the slope toward the yarder, he yelled to his co-worker to radio for help. The yarding engineer had exited the operator’s compartment and was not aware of the victims’ position near the yarder until he heard the witness calling to him. Victim #1 was found lengthwise under the uprooted tree. No signs of breathing or pulse were found. Victim #2 was on his back with the tree across his body. Co-workers performed CPR on Victim #2 and stopped when no signs of breathing or pulse were found. Alaska State Troopers were notified and the bodies recovered. The victims were pronounced dead at the scene.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The medical examiner’s report listed the cause of both deaths as massive crush injuries, [due to being] struck by a falling tree.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Employers should ensure that all crewmembers are capable of recognizing hazardous conditions and are authorized to stop work so that work procedures can be modified in accordance with safe logging and timber harvesting methods.

Discussion: In this case, several aspects of the company’s safety program failed. While it is the responsibility of a siderod to know, convey, and enforce logging safety regulations and company safety policies, it is essential that all employees take action when others fail to see potential hazards. The workers’ right to a safe work environment is promulgated by their responsibility to promote safety individually and collectively. If there is doubt about planning, rigging, location or layout, the best approach is to stop and review the practice or setting.

Recommendation #2: Employers should ensure that all skylines and guylines are anchored to stumps.

Discussion: In this case, the crew’s intent was to anchor the yarder securely and still abide by the “no cut” designation. However, uncut trees used as anchors are inherently more hazardous than stumps due to the above ground stress placed on the root system. The hazard is amplified by additional conditions such as, but not limited to, deterioration or physical damage to the root system and the direction and lean of the tree. Any tree that is a hazard to employees is a “danger tree,” which necessitates its removal. By removing the “danger tree,” leaving it cut and on the ground, and then using the stump as the anchor, the crew would not have compromised the “no cut” designation. If the “no-cut” designation included leaving trees health and alive, the process of notching a tree does irreparable damage that would have killed it.

[Note: Alaska Logging Standard, 8AAC61.1060(m)(13)(L), states that only stumps may be used as anchors for guylines and skylines.]

Recommendation #3: Employers should ensure that all personnel involved in rigging of cable yarding systems are trained in selecting and rigging anchor stumps.

Discussion: In this case, moderate to heavy rain had occurred one day prior to the incident. The slopes above and below the landing and yarding areas appeared moderately saturated. The visible run-off and puddling of water indicated that the ground may be less stable particularly where the upper slope was cut back and vegetation was disturbed during road construction. In addition, many trees in Alaska have shallow root systems due to cold soil and excessive moisture. Steve Conway, author of Logging Practices: Principle of Timber Harvesting Systems, outlines the following general rules for selecting and rigging anchor stumps:

- A stump in deep soil has more holding power that a stump in shallow soil.

- A 48-inch stump has roughly 4x the holding power of a 24-inch stump.

- Stumps have a greater holding capacity with an uphill pull, because of the heavier root structure on the uphill side.

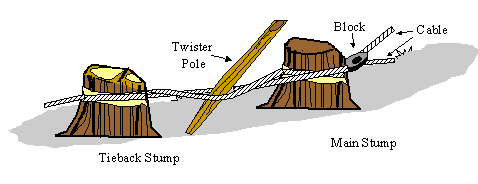

- In wet weather or in areas with relatively shallow soil, use a tieback stump with a main stump to reduce the tension on the root system of the main stump (Figure 3).

- All stumps should be notched to prevent lines from slipping off.

Where an uncut tree is used as a tail hold, multiple anchors, such as a series of tiebacks, should be used. This would have provided decreased the tension on the root system. In addition, an extended safety zone, incorporating the tree height, must be used to prevent the tree from entering the work area.

References

- Alaska Department of Labor, Division of Labor Standards and Safety: Occupational Safety and Health Standards, Additional Logging Standards, 8 Alaska Administrative Code 61.1060. Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Department of Labor, 1995.

- Conway S. Logging practices: principles of timber harvesting systems. Rev. ed. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Publications, 1982.

- Fallers’ and buckers’ handbook, 9th Ed. Vancouver, Canada: Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 1990.

- Logging from felling to first haul. Criteria document for a recommended standard. US Dept of Health, Education and Welfare publication no. (NIOSH) 76-188, 1976.

- Logging safe practices guide, Alaska Timber Insurance Exchange.

- Office of the Federal Register: Code of Federal Regulations, Labor 29 Part 1910. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996.

- United States Forest Service. Alaska Forest Health; Hazard Tree Management. “Hazard tree management in Alaska.” http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r10/forest-grasslandhealth/?cid=fsbdev2_038341 (Link updated 3/27/2013)

Figure 1. Schematic of cable yarding system (Not to scale).

Figure 2. View of swing yarder on access road.

Figure 3. Schematic of anchorage using tieback and main stumps.

Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) Project

The Alaska Division of Public Health, Section of Epidemiology performs Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) investigations through a cooperative agreement with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Division of Safety Research (DSR). The goal of these evaluations is to prevent fatal work injuries in the future by studying the working environment, the worker, the task the worker was performing, the tools the worker was using, the energy exchange resulting in fatal injury, and the role of management in controlling how these factors interact.

To contact Alaska State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.

[1] A person who sets a wire rope (choker) around a log and pulls it tight

[2] A person who unhooks logs at the landing

[3] A landing is an area where a yarder and loader is placed and where cut timber/logs are placed during yarding.

[4] Skidding (pulling) or lifting cut timber to a landing.

[5] A turn is one or more logs moved from their position on the slope to a landing area.

[6] A person who selects and sets up the yarding operation site and may also be responsible for the yarding/loading crew.

[7] A person who assists the hooktender, plans the order of logs to be moved, and supervises the chokesetters.