Notes from the Field: Increase in Human Cases of Tularemia — Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, January–September 2015

Please note: An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here.

, MD1,2; , DVM3; , MPH1,3; , PhD3; , MPH4; 5; , PhD5; , PhD6; , PhD6; , MD6; MD2; DVM2,7

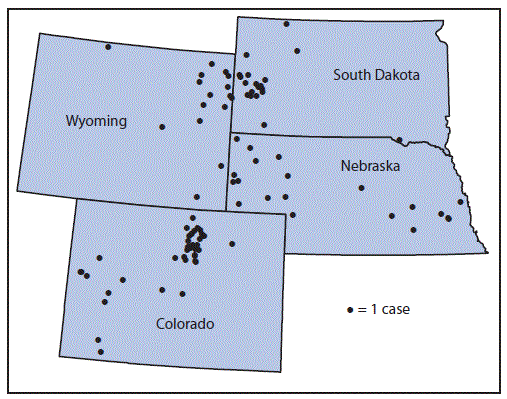

Tularemia is a rare, often serious disease caused by a gram-negative coccobacillus, Francisella tularensis, which infects humans and animals in the Northern Hemisphere (1). Approximately 125 cases have been reported annually in the United States during the last two decades (2). As of September 30, a total of 100 tularemia cases were reported in 2015 among residents of Colorado (n = 43), Nebraska (n = 21), South Dakota (n = 20), and Wyoming (n = 16) (Figure). This represents a substantial increase in the annual mean number of four (975% increase), seven (200%), seven (186%) and two (70%) cases, respectively, reported in each state during 2004–2014 (2).

Patients ranged in age from 10 months to 89 years (median = 56 years); 74 were male. The most common clinical presentations of tularemia were respiratory disease (pneumonic form, [n = 26]), skin lesions with lymphadenopathy (ulceroglandular form, [n = 26]), and a general febrile illness without localizing signs (typhoidal form, [n = 25]). Overall, 48 persons were hospitalized, and one death was reported, in a man aged 85 years. Possible reported exposure routes included animal contact (n = 51), environmental aerosolizing activities (n = 49), and arthropod bites (n = 34); a total of 41 patients reported two or more possible exposures.

Clinical presentation and severity of tularemia depends on the strain, inoculation route, and infectious dose. Tularemia can be transmitted to humans by direct contact with infected animals (e.g., rabbits or cats); ingestion of contaminated food, water, or soil; inhalation from aerosolization (e.g., landscaping, mowing over voles, hares, and rodents, or other farming activities); or arthropod bites (e.g., ticks or deer flies) (1,3). Human-to-human transmission has never been demonstrated (1,3).

Infected persons can develop a range of symptoms that display several clinical forms. These include fever and chills with muscle and joint pain (typhoidal), cough or difficulty breathing (pneumonic), swollen lymph nodes with or without skin lesions (ulceroglandular or glandular), conjunctivitis (oculoglandular), pharyngitis (oropharyngeal), or abdominal pain with vomiting and diarrhea (intestinal) (2,3). Symptoms typically begin within 3–5 days of exposure, but can take up to 14 days to appear. Case fatality rates range from <2%–24%, depending on the strain (1–3). Streptomycin is considered the drug of choice on the basis of historical use and Food and Drug Administration approval; however, it sometimes can be difficult to obtain and is associated with frequent ototoxicity (3). Gentamicin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin are also used (2,3).

F. tularensis is commonly isolated in culture or detected by polymerase chain reaction from patients' blood specimens, but can also be identified in specimens from skin lesions, spinal fluid, lymph nodes, and respiratory secretions (2). In addition, a serologic diagnosis can be made by demonstrating a fourfold increase between immunoglobulin G titers from patients in the acute and convalescent stages of infection. Specimens suspected of containing F. tularensis should be handled at biosafety level 2 at a minimum. Biosafety level 3 containment is recommended when handling live cultures (2,3).

Although the cause for the increases in tularemia cases in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unclear, possible explanations might be contributing factors, including increased rainfall promoting vegetation growth, pathogen survival, and increased rodent and rabbit populations. Increased awareness and testing since tularemia was reinstated as a nationally notifiable disease in January 2000 is also a possible explanation for the increase in the number of cases in these four states (4). Health care providers should be aware of the elevated risk for tularemia within these states* and consider a diagnosis of tularemia in any person nationwide with compatible signs and symptoms. Residents and visitors to these areas should regularly use insect repellent, wear gloves when handling animals, and avoid mowing in areas where sick or dead animals have been reported. Additional information is available at http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia.

1Epidemic Intelligence Service, Division of Scientific Education and Professional Development, CDC; 2Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services; 3Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment; 4Wyoming Department of Health; 5South Dakota Department of Health; 6Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 7Division of State and Local Readiness, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, CDC.

Corresponding author: Caitlin Pedati, CPedati@cdc.gov, 402-471-9148.

References

- Penn RL. Francisella tularensis (tularemia) [Chapter 229]. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- CDC. Tularemia—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:963–6.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on tularemia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/resources/whotularemiamanual.pdf.

- CDC. Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;47 (No. 53).

* As part of this investigation, all bordering states were contacted, and no others reported a similar twofold to threefold increase above baseline for tularemia cases in 2015.

FIGURE. Geographic distribution of reported tularemia cases —Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming,* January–September, 2015

Source: Map of local health departments in Nebraska from Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (available at http://dhhs.ne.gov/publichealth/Documents/LHDMap.pdf).

* Dots indicating cases in Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming are assigned randomly within zip codes; dots indicating cases in Nebraska are assigned randomly within local health department jurisdiction.

Alternate Text: The figure above is a map showing the geographic distribution of reported tularemia cases in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, during January- September, 2015.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.