Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Health of Resettled Iraqi Refugees --- San Diego County, California, October 2007--September 2009

Please note: An erratum

has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please

click here.

In recent years, Iraqi refugees have been resettling in the United States in large numbers, with approximately 28,000 arrivals during October 2007--September 2009 (federal fiscal years [FYs] 2008 and 2009). All refugees undergo a required medical examination before departure to the United States to prevent importation of communicable diseases, including active tuberculosis (TB), as prescribed by CDC Technical Instructions (1). CDC also recommends that refugees receive a more comprehensive medical assessment after arrival, which typically occurs within the first 90 days of arrival. To describe the health profile of resettled Iraqi refugees, post-arrival medical assessment data were reviewed for 5,100 Iraqi refugees who underwent full or partial assessments at the San Diego County refugee health clinic during FYs 2008 and 2009. Among 4,923 screened refugees aged >1 year, 692 (14.1%) had latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI); among 3,047 screened adult refugees aged >18 years, 751 (24.6%) were classified as obese; and among 2,704 screened adult refugees, 410 (15.2%) were hypertensive. Although infectious illness has been the traditional focus of refugee medical screening (2), a high prevalence of chronic, noninfectious conditions that could lead to serious morbidity was observed among Iraqi refugees. Public health agencies should be aware of the potentially diverse health profiles of resettling refugee groups. Medical assessment of arriving refugee populations, with timely collection and review of health data, enables early detection, treatment, and follow-up of conditions, and can help public health agencies develop and set priorities for population-specific health interventions and guidelines.

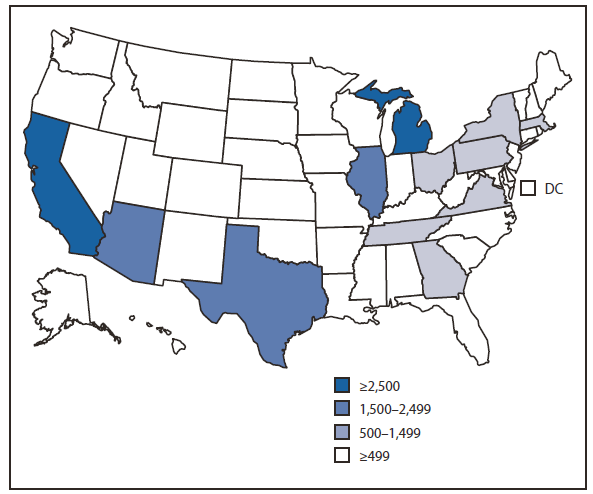

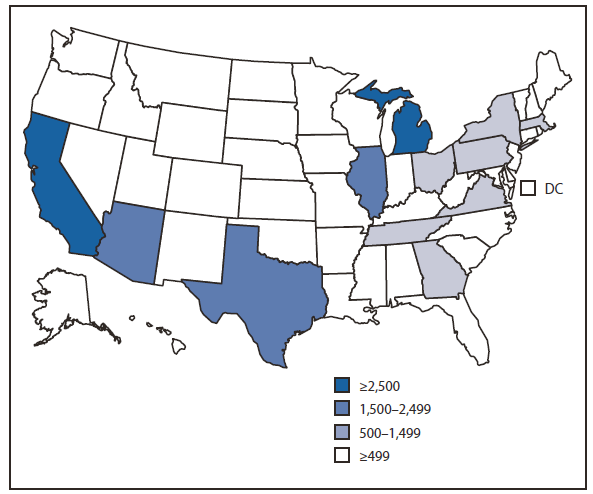

During FYs 2008 and 2009, California received 24% (6,626) of all U.S.-bound Iraqi refugees, the largest proportion of any state (Figure). The California Refugee Health Program provides comprehensive, standardized medical assessments for all refugees within 90 days of arrival. Based on those assessment results, refugees are referred to primary-care providers and, if needed, for specialized care. This initial assessment, based partially on CDC guidelines for arriving refugees (1), includes a history, physical exam, mental health screening, and laboratory screening for infectious conditions such as intestinal parasites, TB, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis B. Depending on age, medical history, and other risk factors, the refugees also are assessed for noninfectious conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anemia, and lead poisoning. This report describes prevalences for selected infectious and noninfectious conditions among Iraqi refugees in California, based on data from those assessments.

San Diego County received 5,397 (81%) of the 6,626 Iraqi refugees who resettled in California during FYs 2008 and 2009 (Table 1). Of these, 5,100 (94.5%) completed at least part of a medical assessment (Table 2), with a median time between arrival and assessment of 76 days (range: 1--159 days). Denominators varied for different components of the medical assessment because of screening criteria (e.g., age) and missing data. Although mental health screening was performed, the data captured were limited and are not presented here.

LTBI was identified in 692 (14.1%) of 4,923 of Iraqi refugees aged >1 year (Table 2). Within the subset of this group aged ≥65 years, the prevalence of LTBI was 52.3%. The only pathogenic intestinal parasites identified by stool examination were Giardia intestinalis in 40 (3.1%)and Entamoeba histolytica in 55 (1.2%) of 4,520 screened refugees; no helminths were identified. All other identified species were of little or indeterminate clinical significance (e.g., Endolimax nana and Blastocystis hominis, respectively) (3). Only 21 (0.7%) of 2,957 refugees of any age were hepatitis B surface antigen-positive, an indication of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Most resettled Iraqi refugees were screened for syphilis and HIV during the required overseas examination. Of 28,366 U.S.-bound Iraqi refugees screened overseas during FYs 2008 and 2009, 27 (0.1%) had syphilis, and only three (<0.1%) were HIV-infected (CDC, unpublished data, 2010). Among 323 Iraqi refugee arrivals in San Diego County who had not been screened overseas for syphilis, eight (2.5%) were found to have the disease. Among 274 arrivals who had not been screened overseas for HIV, only one was found to be infected (Table 2). Among refugees aged >18 years, the most frequently diagnosed noninfectious conditions were obesity in 751 (24.6%) of 3,047 persons and hypertension in 410 (15.2%) of 2,704 persons.* Among those aged ≥65 years, 83 (64.3%) of 129 were hypertensive (Table 2). Of refugees aged ≥40 years who were screened for hyperlipidemia, 114 (39.9%) of 286 had dyslipidemia.† Of children aged <5 years with available anthropometric data, 23 (7.1%) of 322 were acutely malnourished and 348 (29.6%) of 1,175 women of childbearing age were anemic.§

Reported by

M Ramos, PhD, P Orozovich, MPH, California Dept of Public Health, Refugee Health Section. K Moser, MD, San Diego County Dept of Public Health. CR Phares, PhD, W Stauffer, MD, Div of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; T Mitchell, MD, EIS Officer, CDC.

Editorial Note

During the past 3 decades, the United States has received approximately 3 million refugees from diverse countries and regions of the world (4). During FYs 2008 and 2009, Iraqi refugees were the largest group to resettle in the United States, accounting for approximately 21% of all U.S.-resettled refugees.The traditional focus of refugee medical screening has been on communicable diseases (2), and the overseas refugee medical examination emphasizes transmissible illness such as active TB. However, Iraqi refugees were displaced from a middle-income country, where the health profile combines some infectious diseases prevalent in low-income countries (e.g., TB) with chronic conditions seen in the United States (e.g., obesity) (5). The prevalence of obesity among Iraqi adults (24.6%), for example, nearly equaled the prevalence of adult obesity (24.8%) among adult California residents (6). Medical screening after arrival provides an opportunity to identify important causes of morbidity among resettled refugees that might not have been discovered previously, and enables early referral for treatment and follow-up care.

This report highlights key clinical findings among Iraqi refugees in San Diego and provides screening considerations. Chronic, noninfectious conditions were prevalent in this population. This finding is supported by outside data; for example, in a 2009 survey of Iraqi refugees in Jordan and Syria, 41%--51% of refugees aged ≥18 years reported a diagnosis of chronic illness such as hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease (S. Doocy, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, personal communication, 2010). The epidemiology of some infectious diseases in Iraqi refugees also might differ from other refugee groups. For example, although the prevalence of LTBI in Iraqi refugees aged ≥65 years was comparable to rates in other refugee populations (7), recent data from the overseas medical examination indicate that prevalences of abnormal chest radiograph (0.7%) and culture-confirmed TB (0%) among 28,366 Iraqi refugees resettling to the United States during FYs 2008 and 2009 were much lower than those in other recently resettled refugee populations (8). Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection also was lower (0.7%) than country estimates (9) for Iraq (2%--7%) and substantially lower than prevalences seen in some sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian refugee populations, which have been as high as 15% (10).

Few screened Iraqi refugees had evidence of pathogenic intestinal parasites on stool examination (G. intestinalis in 3.1% and E. histolytica in 1.2%). Although Iraqi refugees resettling to the United States from Jordan and Iraq routinely receive presumptive antihelminthic treatment with albendazole (1), none of the Iraqi refugees assessed in San Diego County during FYs 2008 and 2009 (including those from Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, and other countries without presumptive therapy) had evidence of intestinal helminths on stool microscopy. In contrast, other resettling refugee populations have had rates of pathogenic intestinal helminths (e.g., Ascaris spp., Trichuris spp., Ancylostoma spp., and Necator americanus) (3) as high as 24% (2). However, a recent serologic study of 200 Iraqi refugees found that up to 10% were infected with strongyloides and 3.5% with Schistosoma haematobium (CDC, unpublished data, 2009). Stool examination is not a sensitive tool for detection of these parasites, which can cause infection leading to serious health consequences, including death (3).

The health profile described in this report can help local, state, federal, and international public and refugee health agencies identify public health needs of Iraqi refugees resettling in the United States, and provide clinicians with information about relevant medical needs. Considerations for state public health agencies and clinicians include the importance of evaluation for obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia during state medical assessments, with careful screening for diabetes and heart disease among those with risk factors, followed by appropriate referral. Culturally appropriate programs should be implemented to promote obesity prevention and control among Iraqi refugees.

Testing for LTBI should be encouraged and treatment offered to persons with positive test results. Immunization programs in Iraq include bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination, but CDC guidelines state that prior immunization should not be considered in the interpretation of a positive tuberculin skin test or interferon gamma release assay for TB infection (1). In addition, clinicians should consider presumptive treatment or serologic screening for strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis (3), recognizing that the single albendazole dose provided during presumptive treatment in Iraq and Jordan would not eradicate either parasite.

Although rates of chronic malnutrition appear low among Iraqi refugee children aged <5 years, some young children might be acutely malnourished, perhaps because of sudden changes in food availability. In addition to routine assessment of nutritional status with anthropometric measurements and screening for anemia, clinicians should evaluate children aged <5 years for clinical signs of acute malnutrition, such as wasting or bilateral edema.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the medical assessment was limited to the screening described in this report, the results of which might lead to referral for further workup. Therefore, diagnosis of other conditions anecdotally reported in this group of refugees by overseas health-care providers, such as cancers, ischemic heart disease, specific mental health diagnoses, and familial Mediterranean fever, is beyond the scope of the initial assessment. Past medical and family histories, and screening results for some sexually transmitted diseases (i.e., gonorrhea, chlamydia), also were not captured in these data. Second, Iraqi asylees were included in this group of refugees, and their profiles might differ slightly because they sought asylum after arrival in the United States and therefore did not receive predeparture medical examinations. Finally, many refugees were assessed >90 days after arrival; therefore, the original severity of certain conditions might not be reflected (e.g., degree of lead poisoning or presence of intestinal parasitic infections). Delays in medical assessment occurred because the health department was not prepared for the marked increase in Iraqi refugee arrivals during FYs 2008 and 2009 (U.S. arrivals increased from approximately 200 in FY 2007 to approximately 10,000 in FY 2008).

CDC and state public health departments should continue to collaborate to improve collection, review, and sharing of health data for arriving refugee populations. Timely data collection is a corollary of timely medical assessment. Improved planning for and communication regarding sudden increases in refugee arrival could help reduce the time to assessment and allow for earlier detection and referral of important medical conditions. A comprehensive and evidence-based understanding of the unique health profile of each incoming refugee population ultimately would allow development of beneficial, population-specific, and cost-effective screening and therapeutic guidelines for refugees.

Acknowledgments

This report is based, in part, on contributions by L Scott, MD, C Zavala, and Refugee Health Section staff members, California Dept of Public Health; San Diego County Refugee Health Program staff members; R Moser, PhD, San Diego Catholic Charities; and H Burke, MPH, C Godwin, Z Wang, MS, M Weinberg, MD, and E Yanni, MD, Div of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC.

References

- CDC. Medical examination of immigrants and refugees [Internet site]. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/medical-examination.html. Accessed April 30, 2010.

- Barnett ED. Infectious disease screening for refugees resettled in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:833--41.

- CDC. Domestic intestinal parasite guidelines [Internet site]. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/intestinal-parasites-domestic.html#table2. Accessed August 17, 2010.

- US Department of State. FY 2010 cumulative summary of refugee admissions. Washington, DC: US Department of State, Refugee Processing Center; 2010. Available at http://www.wrapsnet.org/reports/archives/tabid/215/language/en-us/default.aspx. Accessed April 29, 2010.

- Arredondo A. Costs and financial consequences of the changing epidemiological profile in Mexico. Health Policy 1997;42:39--48.

- CDC. U.S. obesity trends, 2009. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html#state. Accessed December 13, 2010.

- Varkey P, Jerath AU, Bagniewski SM, Lesnick TG. The epidemiology of tuberculosis among primary refugee arrivals in Minnesota between 1997 and 2001. J Travel Med 2007;14:1--8.

- Liu Y, Weinberg MS, Ortega LS, Painter JA, Maloney SA. Overseas screening for tuberculosis in U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2406--15.

- CDC. The pre-travel consultation: hepatitis B. In: Health information for international travel 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2009. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-2/hepatitis-b.aspx. Accessed April 29, 2010.

- Rein RB, Lesesne SB, O'Fallon A, Weinbaum CM. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen among refugees entering the United States between 2006 and 2008. Hepatology 2010;51:431--4.

What is already known on this topic?

Iraqi refugees are now the largest refugee group resettling to the United States; although they receive a standard medical exam overseas before resettlement and a recommended, more comprehensive health assessment after arrival, information about the health status of Iraqi refugees from these assessments had not been summarized previously.

What is added by this report?

Some infectious conditions that have been the traditional focus of refugee health assessment, such as latent tuberculosis, are prevalent in Iraqi refugees, but noninfectious, chronic conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia, also are prevalent and important concerns in this population.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Refugee populations resettling to the United States might have diverse health profiles; population-specific health information will assist local, state, and federal public health agencies develop more focused screening, prevention, treatment, and referral efforts aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality.

FIGURE. Number of Iraqi refugee arrivals --- United States, October 2007--September 2009

Alternate Text: The figure above shows Iraqi refugee arrivals, by state in the United States during October 2007-September 2009. During that period, California received 24% (6,626) of all U.S.-bound Iraqi refugees, the largest proportion of any state.

|

|

Arrivals*

|

|

Characteristic

|

No.

|

(%)†

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

Male

|

2,781

|

(51.5)

|

|

Female

|

2,616

|

(48.5)

|

|

Age group (yrs)

|

|

|

|

<5

|

509

|

(9.4)

|

|

5--18

|

1,451

|

(26.9)

|

|

19--25

|

822

|

(15.2)

|

|

26--45

|

1,664

|

(30.8)

|

|

46--65

|

777

|

(14.4)

|

|

≥65

|

174

|

(3.2)

|

|

Most recent country of residence§

|

|

|

|

Iraq

|

249

|

(4.6)

|

|

Jordan

|

1,082

|

(20.0)

|

|

Lebanon

|

855

|

(15.8)

|

|

Syria

|

1,101

|

(20.4)

|

|

Turkey

|

1,803

|

(33.4)

|

|

Other

|

307

|

(5.7)

|

|

Highest level of education (yrs)¶

|

|

|

|

None

|

146

|

(4.8)

|

|

Elementary (1--6)

|

485

|

(15.9)

|

|

Junior high school (7--8)

|

274

|

(9.0)

|

|

High school (9--12)

|

1,130

|

(37.0)

|

|

Some college (13--16)

|

804

|

(26.3)

|

|

College graduate (>16)

|

213

|

(7.0)

|

|

Conditions

|

Definition

|

Screened groups*

|

No. screened refugees†

|

Positive

|

|

No.

|

(%)

|

|

Noninfectious

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anemia

|

Children aged <2 yrs: capillary Hgb <11.0 g/dL

|

>9 mos

|

5,100

|

457

|

(9.0)

|

|

|

<5 yrs

|

540

|

89

|

(16.5)

|

|

Females aged ≥2 yrs: capillary Hgb <12.0 g/dL

|

Females aged 19--45 yrs

|

1,175

|

348

|

(29.6)

|

|

Males aged ≥2 yrs: capillary Hgb <13.0 g/dL

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dyslipidemia

|

Elevated fasting LDL-C or TG or low HDL-C

|

≥40 yrs

|

286

|

114

|

(39.9)

|

|

Glucosuria

|

Urine dipstick glucose results ≥50 mg/dL

|

≥4 yrs

|

4,755

|

69

|

(1.5)

|

|

|

>18 yrs

|

3,245

|

61

|

(1.9)

|

|

Hypertension

|

Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on two separate measurements

|

≥3 yrs

|

2,805

|

415

|

(14.8)

|

|

|

≥65 yrs

|

129

|

83

|

(64.3)

|

|

Lead poisoning

|

Blood lead level ≥10 µg/dL

|

1--5 yrs

|

372

|

5

|

(1.3)

|

|

Malnutrition, acute

|

Weight-for-height z-score <-2

|

<5 yrs

|

322

|

23

|

(7.1)

|

|

Malnutrition, chronic

|

Height-for-age z-score <-2

|

<5 yrs

|

329

|

14

|

(4.3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obesity

|

BMI ≥30 kg/m2

|

All

|

4,734

|

793

|

(16.8)

|

|

|

≤18 yrs

|

1,687

|

42

|

(2.5)

|

|

|

>18 yrs

|

3,047

|

751

|

(24.6)

|

|

Infectious

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hepatitis B

|

HBsAg positive

|

≥12 yrs

|

2,957

|

21

|

(0.7)

|

|

|

>18 yrs

|

2,475

|

19

|

(0.8)

|

|

HIV

|

ELISA followed by Western blot

|

Asylees only§

|

274

|

1

|

(0.4)

|

|

Intestinal parasites (any)¶

|

At least one positive sample from three stool ova and parasites tests

|

All

|

4,520

|

2,091

|

(46.3)

|

|

|

<5 yrs

|

400

|

88

|

(22.0)

|

|

B. hominis

|

|

All

|

|

1,450

|

(32.1)

|

|

E. nana

|

|

All

|

|

218

|

(4.8)

|

|

D. fragilis

|

|

All

|

|

169

|

(3.7)

|

|

G. intestinalis

|

|

All

|

|

140

|

(3.1)

|

|

E. histolytica

|

|

All

|

|

55

|

(1.2)

|

|

Latent tuberculosis

|

Positive tuberculin skin test on children aged <12 yrs; positive IGRA on persons aged ≥12 yrs

|

≥1 yrs

|

4,923

|

692

|

(14.1)

|

|

|

≥65 yrs

|

153

|

80

|

(52.3)

|

|

Syphilis

|

Positive RPR and TP-PA or FTA-ABS

|

≥12 yrs (patients not already screened overseas)§

|

323

|

8

|

(2.5)

|

|

|

>18 yrs

|

304

|

8

|

(2.6)

|

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.