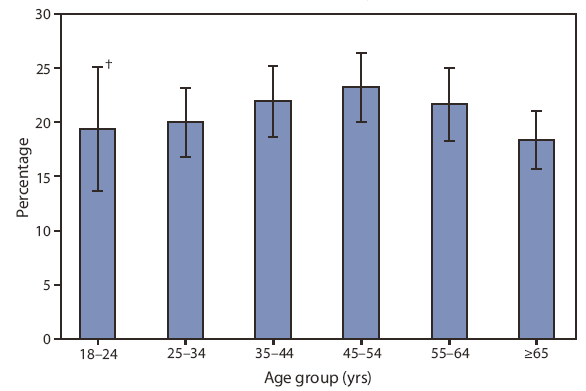

FIGURE. Percentage of respondents aged ≥18 years* who reported receiving a prescription opioid medication in the preceding 12 months, by type of pain and age group --- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Utah, 2008

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Adult Use of Prescription Opioid Pain Medications --- Utah, 2008

Fatal and nonfatal overdoses from prescription pain medications have increased in recent years in Utah and throughout the nation (1,2). In 2008, the Utah Department of Health added 12 questions to the state's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey to better understand how state residents obtain and use prescription pain medication. Findings from the survey indicated that an estimated 20.8% of Utah adults aged ≥18 years had been prescribed an opioid pain medication during the preceding 12 months. Of those prescribed an opioid pain medication, 3.2% reported using their medication more frequently or in higher doses than had been directed by their doctor; 72.0% reported having leftover medication, and 71.0% of those with leftover medication reported that they had kept the medication. Approximately 1.8% of all adults reported using prescription opioids that had not been prescribed to them. In 2009, the Utah Department of Health published a set of guidelines to reduce morbidity, mortality, and disability associated with misuse or abuse of prescription drugs, especially narcotics. The guidelines include recommendations that providers 1) counsel patients to dispose of unused medication properly once the pain has resolved and 2) prescribe no more than the number of doses needed based on the usual duration of pain severe enough to require opioids for that condition (3).

BRFSS conducts state-based, random-digit--dialed telephone surveys of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged ≥18 years, collecting data on health conditions and health risk behaviors. The Utah BRFSS is conducted in the state's 12 health districts; rural health districts with smaller populations are sampled at higher rates than urban health districts with larger populations (4). This oversampling of less populated districts is intended to produce reliable estimates for commonly used measures within each district. In 2008, the Utah Department of Health added 12 questions regarding use of prescription pain medications to the state BRFSS survey.* For this analysis, only responses regarding opioid pain medications are included in the results. In 2008, a total of 5,330 respondents were interviewed for the Utah BRFSS. The overall Council of American Survey Research Organizations response rate for Utah in 2008 was 63.8%. Percentages were weighted by age, race, and sex to mirror the Utah adult population aged ≥18 years. Statistical significance of differences was determined by chi-square test.

In 2008, 20.8% of participants reported using at least one prescribed opioid medication during the preceding 12 months.† Of those who reported being prescribed an opioid, 71.0% said they were prescribed the drug for short-term pain, 14.7% said they were prescribed the drug for long-term pain, and 14.4% said they were prescribed the drug for both short-term and long-term pain.§ Receiving prescription opioids was more common among adults aged 35--64 years and most common among those aged 45--54 years (Figure).

Of respondents prescribed at least one opioid during the preceding 12 months, 72.0% had leftover medication¶ from their most recently filled prescription. Of those with leftover medication, 71.0% reported that they had kept the medication,** 25.2% had disposed of the medication, and 2.3% had given the medication to someone else (Table). Among respondents, 3.2% of those who had received a prescription opioid reported using the medication more frequently or in higher doses than directed by their doctor.††

In 2008, 1.8% of BRFSS respondents reported using prescription opioid medication that had not been prescribed for them. Of those respondents, 97.0% said they obtained the medication from a friend or relative, and 72.4% said they obtained it to relieve pain. When asked how the medication was obtained, 85.2% said the medication was given to them, 9.8% said the medication was taken without the knowledge or permission of the owner, and 4.1% said it was purchased (Table).§§ Persons aged 35--44 years were most likely to report using opioid medication that was not prescribed for them. The percentages of males and females reporting this behavior were approximately the same for all age groups with no statistically significant differences by sex.

Of respondents who reported they had been prescribed an opioid pain medication in the preceding 12 months, hydrocodone was the opioid most often prescribed (69.3% [95% confidence interval {CI} = 65.4%--73.0%]), followed by oxycodone (27.5% [CI = 23.7%--31.4%]). Of respondents who said their opioid prescription was for short-term pain, 71.0% (CI = 66.4%--75.6%) reported being prescribed hydrocodone, compared with 60.1% (CI = 51.7%--68.4%) of persons who said their prescription was for long-term pain (p = 0.01).

Reported by

CA Porucznik, PhD, Univ of Utah; BC Sauer, PhD, Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Center; EM Johnson, MPH, J Crook, J Wrathall, MPH, JW Anderson, MPH, RT Rolfs, MD, Utah Dept of Health.

Editorial Note

The findings in this report indicate that use of prescription pain medications is common in Utah, with 20.8% of respondents reporting they had been prescribed an opioid pain medication during the preceding 12 months. This percentage is comparable to the 18.4% of insured persons aged ≥18 years who reported receiving a prescription for opioids in a national study in 2002 (5). The findings in this report also indicate that a small percentage of persons (1.8%) obtained prescription opioids that had not been prescribed for them, and the most common reason reported for using prescription opioids not prescribed to these persons was to relieve pain (72.4%). This report appears to be the first of its kind to use pain medication questions added to BRFSS, although Kansas added a module of questions regarding chronic pain in 2005 and 2007 with one follow-up question asking how the pain was treated. Additional studies can provide further understanding of the complexities of pain medication prescription practices and usage in other states. Because prescription practices might vary among states, such information likely will be valuable in formulating state and federal policies on opioid pain medication prescription and use.

During 1999--2007, deaths in Utah attributed to poisoning by prescription pain medications increased nearly 600%, from 39 in 1999 to 261 in 2007. Although the extent to which leftover medications contribute to overdose deaths is unknown, the 1.8% of respondents who reported using prescription opioids that had not been prescribed to them extrapolates to approximately 35,000 adults in Utah engaged in illegal and risky behavior (6,7). The findings from this survey also suggest that providers commonly prescribe more doses than are used by patients. Of respondents who received opioid pain prescriptions, 72.0% indicated they had leftover medication from their last refill, and 71.0% of those persons kept their medication. In 2009, the Utah Department of Health recommended that, when opioid medications are prescribed for treatment of acute pain, the number dispensed should be no more than the number of doses needed based on usual duration of pain severe enough to require opioids for that condition (3). Prescribing more medication than the amount likely to be needed can make unused medication available for misuse and abuse. However, the Utah Department of Health guidelines also acknowledge that undertreatment of pain is a serious public health problem and emphasizes the importance of balance in treating pain appropriately (3).

Despite the fact that sharing controlled substances is a felony in Utah (7), such sharing occurs. However, nearly all respondents who used someone else's medication received it from a friend or relative (97.0%), and when asked how the medication was obtained, 85.2% said they were given it without charge. These findings correspond with data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) showing that 56.5% of persons who used prescription pain medications nonmedically obtained them for free from family members or friends (8). One area for public health action is to educate patients to properly dispose of leftover medication (9). Disposing of leftover medication will prevent accidental use by children, pets, or anyone else (9) as well as prevent theft for misuse.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, BRFSS data are self-reported, and therefore subject to recall and social desirability bias. Second, interviews are conducted by landline telephone, and households without a landline telephone are excluded from the survey. Third, sample sizes for certain subgroups were small, and those results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, certain questions inquired into activities that respondents might be reluctant to discuss (e.g., using a prescription medication that had not been prescribed to them), which could result in social desirability bias and an underestimate.

Leftover opioid medications represent a potential danger that might be reduced with different prescribing practices and closer prescription monitoring (Box). Identifying and publicizing acceptable options for patients with leftover medications (e.g., mixing pills with an undesirable substance and throwing them in the garbage, or utilizing law enforcement drop boxes) also might increase frequency of proper disposal (9).

References

- CDC. Increase in poisoning deaths caused by non-illicit drugs---Utah, 1991--2003. MMWR 2005;54:33--6.

- Fingerhut LA. Health e-stats. Increases in poisoning and methadone-related deaths: United States, 1999--2005. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/poisoning/poisoning.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Sundwall DN, Rolfs RT, Johnson E. Utah clinical guidelines on prescribing opioids for treatment of pain. Utah Department of Health; 2009. Available at http://health.utah.gov/prescription/pdf/guidelines/final.04.09opioidguidlines.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2010.

- Utah Department of Health Office of Public Health Assessment. Utah Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Available at http://health.utah.gov/opha/opha_brfss.htm. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Williams RE, Samson TJ, Kalilani L, Wurzelmann JI, Janning SW. Epidemiology of opioid pharmacy claims in the United States. J Opioid Manag 2008;4:145--52.

- Utah Department of Health. Population estimates query module selection configuration. Available at http://ibis.health.utah.gov/query/selection/pop/PopSelection.html. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Utah State Legislature. Utah code, Title 58, Chapter 37, Section 8: Prohibited acts---penalties. Available at http://le.utah.gov/~code/title58/htm/58_37_000800.htm. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2007 national survey on drug use and health: national findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2008. Available at http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k7nsduh/2k7results.cfm#2.16. Accessed February 12, 2010.

- Food and Drug Administration. Disposal by flushing for certain unused medicines: what you should know. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA. Revised 2009. Available at http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/ensuringsafeuseofmedicine/safedisposalofmedicines/ucm186187.htm. Accessed February 12, 2010.

* Available at http://health.utah.gov/opha/publications/brfss/questionnaires/08utbrfss.pdf.

† In response to the questions, "In the past year, did you use any pain medications that were prescribed to you by a doctor?" and "In the past year, what pain medications were prescribed to you by a doctor?" All reported pain medications were noted. For this analysis, only prescription opioids were included.

§ Percentages do not add to 100.0% because of rounding.

¶ In response to the question, "The last time you filled a prescription for pain medication was there any medication left over?"

** In response to the question, "What did you do with the leftover prescription medication?"

†† In response to the question, "The last time you filled a prescription for pain medication, did you use any of the pain medication more frequently or in higher doses than directed by a doctor?"

§§ In response to the question, "How did you obtain the prescription pain medication from this source [given to you, purchased, or taken without the person's knowledge or permission]?"

What is already known on this topic?

In 2005, Utah had the highest rates in the nation of reported nonmedical use of pain relievers, as well as an increase in prescription opioid--related deaths.

What is added by this report?

An estimated 72% of respondents who were prescribed an opioid had leftover medication, and 71% of those with leftover medication kept it; during the same period, 97% of those who used opioids that were not prescribed to them said they received them from friends or relatives.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Utah has recommended that providers counsel patients to dispose of unused medication properly once the pain has resolved, and prescribe no more than the number of doses needed based on the usual duration of pain severe enough to require opioids for that condition.

* N = 5,330.

† 95% confidence interval.

Alternative Text: The figure above shows the percentage of respondents aged ≥18 years who reported receiving a prescription opioid medication in the preceding 12 months, by type of pain and age group in Utah in 2008. Receiving prescription opioids was more common among adults aged 35-64 years and most common among those aged 45-54 years.

|

BOX. Measures to prevent misuse of opioid prescription medications |

|

Providers can reduce the amount of opioid medication available for nonmedical use by • Using opioid medications for acute or chronic pain only after determining that alternative therapies do not deliver adequate pain relief. The lowest effective dose of opioids should be used. • Reserving use of long-acting or sustained-release opioids (e.g., OxyContin or methadone) for the treatment of long-term pain. • Seeking specialty consultation if patients continue to experience severe pain without functional improvement despite treatment with opioids. • Periodically requesting a report on the prescribing of opioids to their patients by other providers. Such reports generally are available from the state prescription drug monitoring program. State and federal agencies can reduce the risks resulting from misuse of opioid analgesics by • Making substance abuse treatment services widely available. • Monitoring Medicaid prescription claims information for signs of inappropriate use of opioid medication (e.g., multiple prescriptions for the same medication from different physicians), and notifying the physicians that the patient might be misusing the medication. • Proactively using state prescription drug monitoring programs to identify patients and providers with signs of inappropriate use, prescribing, or dispensing of opioid medications. SOURCES: Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al; American Pain Society---American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10:113--30. Washington State Agency Medical Directors' Group. Interagency guideline on opioid dosing for chronic non-cancer pain: an educational pilot to improve care and safety with opioid treatment. Available at http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov. Accessed February 16, 2010. Sundwall DN, Rolfs RT, Johnson E. Utah clinical guidelines on prescribing opioids for treatment of pain. Utah Department of Health; 2009. Available at http://health.utah.gov/prescription/pdf/guidelines/final.04.09opioidguidlines.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2010. |

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.