Summary of Possible Multistate Enteric (Intestinal) Disease Outbreaks in 2017–2020

CDC’s Investigations of Possible Multistate Outbreaks Caused by Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, and Listeria monocytogenes

Possible Multistate Outbreaks

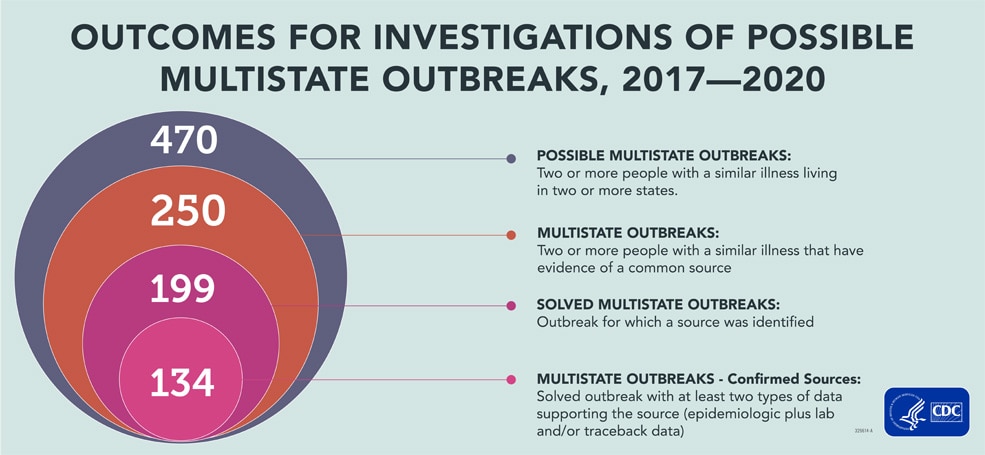

This analysis includes 470 possible multistate outbreak investigations during 2017–2020. Some possible outbreaks were excluded from this summary because they were determined to be single state or because they were linked to international travel. After investigation, 250 (53%) of these were determined to be multistate outbreaks, and investigators solved 199 (80%) of these outbreaks. Among solved outbreaks, there was enough information to confirm the source for 134 (67%) outbreaks.

Multistate Outbreaks

The number of multistate outbreaks investigated each year ranged from 47 to 82; the numbers increased from 2017 to 2019. The increase in investigated outbreaks, especially between 2018 and 2019, may have been a result of implementing whole genome sequencing in PulseNet. The number of investigated outbreaks fell in 2020, driven by a reduction in the number of Salmonella and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) outbreaks investigated. The COVID-19 pandemic likely contributed to the decrease in 2020 by decreasing resources at local, state, and federal public health agencies for enteric disease outbreak detection and investigation. It also likely decreased the ability or willingness of people to seek medical care, which might have decreased the number of illnesses and outbreaks identified. A true decrease in foodborne illnesses during this time might also have played a role, given the impact of the pandemic on eating and grocery shopping patterns.

Figure 1. Number of Multistate Outbreaks Investigated, by Year and Pathogen

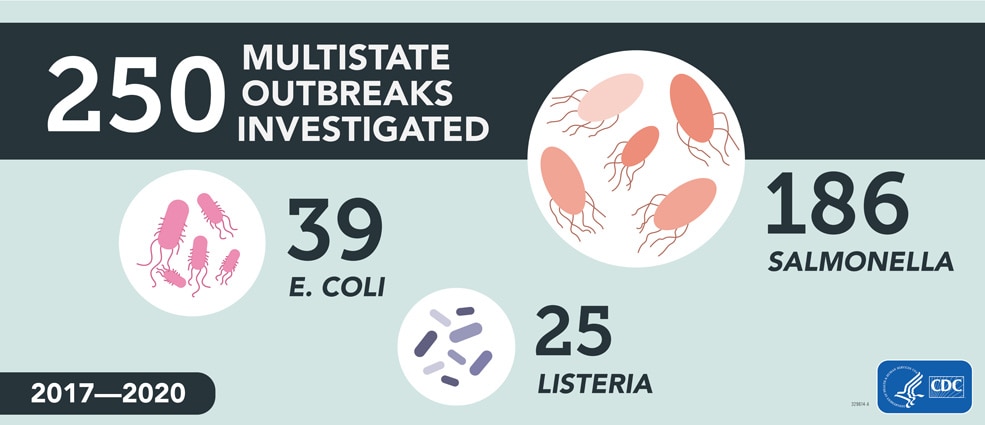

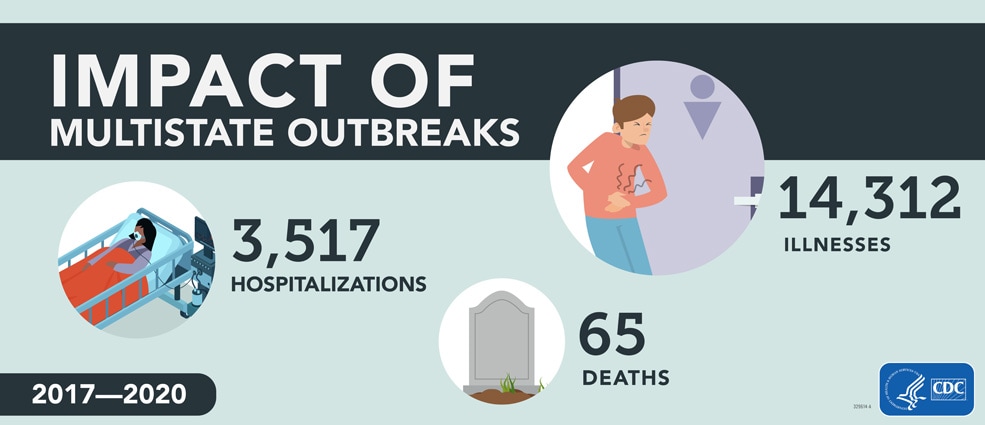

The 250 investigated multistate outbreaks resulted in 14,312 illnesses, 3,517 hospitalizations, and 65 deaths. These numbers substantially underrepresent the true number of illnesses caused by these outbreaks because many people do not seek medical care or do not get tested to see what bacteria could be causing their illness. Without testing, illnesses cannot be identified as being part of a multistate outbreak. Consistent with what was reported in the 2016 summary [PDF – 56 pages], Salmonella caused the highest number of outbreaks and illnesses, comprising about three-quarters (74%) of the possible outbreaks and the overwhelming majority (89%) of illnesses.

Solved Multistate Outbreaks

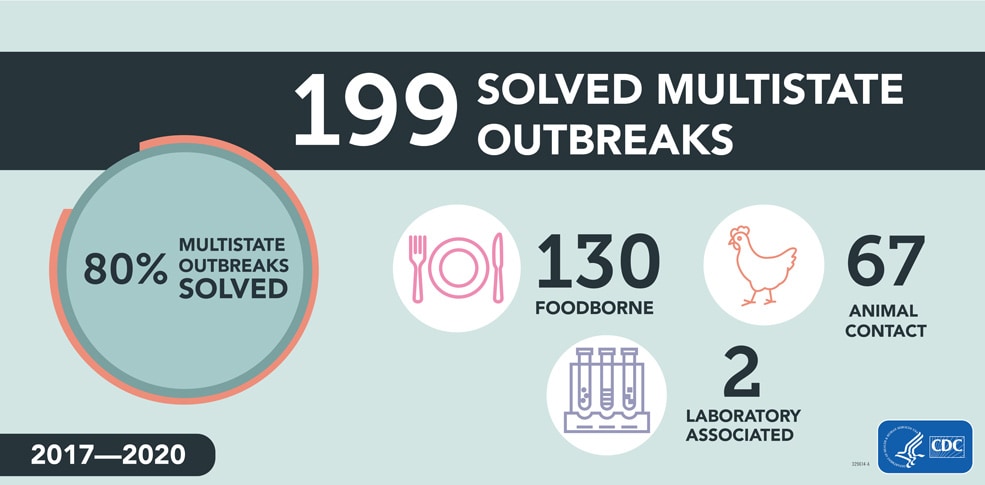

Among the 250 investigated multistate outbreaks, 199 (80%) were solved, including 134 outbreaks with confirmed sources and 65 with suspected sources. Among the 199 solved multistate outbreaks, 130 (65%) were linked to contaminated foods, 67 (34%) were linked to animal contact, and 2 (1%) were linked to exposure to a Salmonella strain used in microbiology laboratories.

Figure 2. Solved Multistate Foodborne and Animal Contact Outbreaks by Year

During 2017–2020, investigators solved 20–50 multistate foodborne outbreaks and 11–23 multistate animal contact outbreaks each year. Solved multistate outbreaks linked to contaminated food caused between 838 and 2,940 known illnesses each year. Solved multistate outbreaks linked to animal contact caused between 408 and 1,897 known illnesses each year.

Figure 3. Illness in Multistate Foodborne and Animal Contact Outbreaks during 2017–2020, by Year

Public Health Actions

When investigators find the food or animal source of a multistate outbreak, they can take actions, such as recalling foods, closing facilities, and issuing outbreak notices. Warning consumers quickly about contaminated foods or animal contact outbreaks can prevent illnesses and save lives. Not every multistate outbreak with a confirmed source results in product actions or outbreak notices. Outbreaks may end by the time the source is confirmed, or investigators may determine that the contaminated food is no longer on the market.

From 2017 through 2020, CDC issued 65 outbreak notices, including 52 linked to contaminated foods, and 13 linked to animal contact. Not every multistate outbreak notice was linked to a confirmed source; CDC also issues multistate outbreak notices when a source is unknown or suspected, depending on the severity of the public health concern. Among the 134 multistate outbreaks with a confirmed source, 43 resulted in product recalls or withdrawing the contaminated product from the market. CDC notified approximately 4,000 reporters and news outlets of multistate outbreak investigations. CDC used social media to deliver information about multistate outbreaks and public health recommendations to a wide audience. In 2018 and 2019, CDC Facebook posts for foodborne outbreaks were among the top three performing posts out of all CDC posts in those years. These three Facebook posts had over 11 million impressions combined.

2018

- Romaine Lettuce E. coli outbreak, April (3,057,116 impressions)

- Romaine Lettuce E. coli outbreak, November (6,777,484 impressions)

2019

- Pre-cut melon Salmonella outbreak (1,173,300 impressions)

More information about CDC’s framework for making risk communication decisions during foodborne outbreaks can be found on the Issuing Foodborne Outbreak Notices web page.

Salmonella and Ground Beef

Why were these outbreaks notable?

Ground beef was the source of two large multistate Salmonella outbreaks caused by the same outbreak strain. During a 2016–2017 outbreak, the strain causing illnesses was also found in cattle. In 2018, the same strain caused one of the largest ground beef–associated outbreaks in decades, resulting in the recall of 12.1 million pounds of beef. In both outbreaks, investigators traced ground beef to several slaughter/processing establishments, but could not identify the farms that supplied cattle to the establishments, limiting the ability to determine what caused illnesses from the same strain over many years.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

These outbreaks highlighted the need for improved traceability of cattle to facilitate root cause investigations and to identify food safety gaps. CDC identified Salmonella and ground beef as one of its prevention priorities aimed at promoting effective interventions. Although not a result of these outbreaks, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) has proposed updated Salmonella performance standards for ground beef and beef trim.

STEC O157 and Leafy Greens

Why were these outbreaks notable?

The largest multistate STEC O157 outbreak in decades occurred in spring 2018 and was linked to romaine lettuce from multiple farms in the Yuma, Arizona, growing region. Another strain of STEC O157 caused reoccurring fall outbreaks, including outbreaks in 2018 and 2019 linked to romaine from growing regions in the Central Coast of California. Environmental assessments suggested agricultural water, and possibly cattle, may have contributed to the contamination of leafy greens with STEC O157 in these outbreaks.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

CDC identified STEC and leafy greens as a prevention priority. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released the FDA Leafy Greens STEC Action Plan, calling for action to improve the safety of leafy greens, and has proposed amendments to agriculture water requirements for produce safety. The leafy greens industry began voluntarily labeling prepackaged leafy greens to help identify where they were grown. The California [PDF – 103 pages] and Arizona Leafy Green Marketing Agreements [PDF – 90 pages] issued updated recommendations to producers to help them reduce the risk of contamination during leafy green production.

Listeria and Deli Meats and Cheeses

Why were these outbreaks notable?

In 2018, investigators linked a multistate Listeria outbreak to ready-to-eat (RTE) deli ham, the first time since 2005 that a multistate listeriosis outbreak was linked to a USDA-FSIS-regulated product. In 2019, deli-sliced meats or cheeses were the suspected source of another listeriosis outbreak. The outbreak strain was found in environmental samples collected from multiple deli locations, and patients reported consuming a variety of deli meats and cheeses, suggesting that cross-contamination was occurring in delis. These outbreaks demonstrate that RTE meats and cheeses remain a risk for listeriosis. In particular, RTE meats and cheeses sliced in a retail deli may pose a risk due to the potential for cross-contamination.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

USDA-FSIS updated FSIS Directive 10,240.3, FSIS Ready-to-Eat Sampling [PDF – 23 pages], and FSIS Directive 10,240.4, Listeria Rule Verification Activities [PDF – 20 pages], on March 25, 2022. FSIS added a related study to its Food Safety Research Priorities and updated its Appendix A cooking guidance for meat and poultry products.

Salmonella and Raw Turkey and Chicken Products

Why were these outbreaks notable?

During 2017–2019, two multistate outbreaks of Salmonella linked to raw poultry products sickened 487 people: Salmonella Infantis infections linked to raw chicken products and Salmonella Reading infections linked to raw turkey products. During both investigations, outbreak strains were found in a variety of raw poultry products, raw pet food, and live poultry. No common food product or supplier was identified in either outbreak. The variety of products and sources identified indicated widespread contamination throughout the chicken and turkey industries. These outbreaks both occurred following the release of more stringent Salmonella performance standards for poultry products by USDA-FSIS in 2016.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

The Salmonella Reading outbreak resulted in recalls of ground turkey and raw turkey pet food products. After the outbreaks, CDC and FSIS shared findings with the turkey and chicken industries and encouraged industry to implement strategies to reduce these strains of Salmonella throughout the production chain. In 2021, USDA-FSIS initiated efforts to reduce Salmonella illnesses linked to poultry.

Salmonella and Contact with Small Mammals

Why were these outbreaks notable?

During 2018–2020, three multistate Salmonella outbreaks were linked to contact with small mammals, demonstrating the continued risk of Salmonella transmission from contact with pets such as guinea pigs and hedgehogs. These investigations highlighted how animal care, transportation, and housing (e.g., crowding) can contribute to the burden of Salmonella in small mammals.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

CDC worked with small mammal breeders, distributors, and pet stores to revise best husbandry practices to reduce Salmonella, consult with a veterinarian to perform testing in their breeding populations, and educate new pet owners about risk of Salmonella transmission.

Salmonella and Pig Ear Pet Treats for Dogs

Why were these outbreaks notable?

This was the first multistate outbreak of Salmonella in the United States linked to pig ear pet treats. Multiple strains of Salmonella were detected, many of which were multidrug resistant (MDR), from pig ear pet treats imported from several countries. The outbreak highlighted the risk of illness associated with feeding pets pig ear treats and possibly other pet treats. It highlights the interconnectivity of human health with companion animal ownership and the need for improved surveillance for imported pet food products.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

In July 2019, FDA posted answers to frequently asked questions from members of the pig ear pet supply chain (manufacturers, suppliers, importers, distributors, retailers) regarding Salmonella control in these products. Several firms recalled pig ear treats. No single supplier, distributor, or common brand of pig ear treats was identified. An import alert was issued for imported pig ear pet treats.

Salmonella and Contact with Cattle

Why were these outbreaks notable?

Between 2015 and 2018, Salmonella sickened 68 people who reported contact with dairy calves, the first multistate outbreak of MDR Salmonella Heidelberg linked to cattle exposure. The outbreak strain was found in sick people, sick cattle, and environmental samples from a livestock market. Infection likely spread from infected calves to humans, although not all infected calves were obviously sick. This outbreak emphasized the importance of a “One Health” approach when handling livestock to prevent illness transmission between animals and people.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

CDC, several states, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) provided advice for livestock handlers, veterinarians, and healthcare providers to prevent illness when handling livestock, report laboratory-confirmed Salmonella Heidelberg to their state animal health official, and consider MDR Salmonella Heidelberg infection in differential diagnosis of patients with exposure to cattle, farms, or farm workers.

Salmonella and Contact with Backyard Poultry

Why were these outbreaks notable?

During 2020, Salmonella illnesses linked to backyard poultry surpassed the numbers seen in previous years. In 2020, backyard poultry outbreaks were caused by 12 Salmonella serotypes, resulting in 1,737 illnesses, 333 hospitalizations, and 2 deaths. Illnesses were reported from all 50 states. This was both the highest number of backyard poultry–associated Salmonella outbreaks and the highest total number of outbreak-associated illnesses in a one-year period on record for the United States. An increase in live poultry purchases during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic might have contributed to the number of illnesses.

What happened as a result of these outbreaks?

CDC worked with hatcheries and stores that sell poultry to educate new poultry owners and control the spread of Salmonella at hatcheries. Increased capacity at CDC led to improved investigation processes to examine the rise in Salmonella linked to backyard poultry, information on consumer attitudes and behaviors of new poultry owners during the COVID-19 pandemic, and expanded prevention education. However, there are still capacity needs at the state level to investigate these yearly outbreaks.

Figure 4: Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks During 2017–2020, By Year and Pathogen

Of the 199 solved multistate outbreaks, 130 were confirmed or suspected to be linked to contaminated foods.

Among all illnesses related to solved foodborne outbreaks, 9% occurred in children under 5, and 20% occurred among adults over 65 years, age groups at higher risk for severe illness.

These multistate outbreaks were associated with 7,659 illnesses, 2,044 hospitalizations, and 41 deaths. Ill people in these outbreaks ranged in age from less than 1 year to 105 years, with a median age of 39; 57% were female. Among all illnesses related to solved multistate foodborne outbreaks, 9% occurred in children under 5, and 20% occurred among adults over 65 years, age groups at higher risk for severe illness. When compared with Salmonella and STEC infections, a higher proportion of Listeria infections occurred in adults over 65 years (56%).

Salmonella caused the most multistate outbreaks (83 outbreaks, 64%), followed by STEC (29 outbreaks, 22%), then Listeria (18 outbreaks, 14%). Among multistate foodborne outbreaks, Salmonella outbreaks tended to be larger (median: 30 illnesses, range: 2–1,132) compared to those caused by STEC (median: 21 illnesses, range: 6–239) and Listeria (median: 7.5 illnesses, range: 2–36).

Figure 5: Illnesses in Solved Foodborne Outbreaks

Table 1: Hospitalizations in Solved Foodborne Outbreaks

| Pathogen | Number of Hospitalizations |

|---|---|

| STEC | 419 |

| Listeria | 136 |

| Salmonella | 1,489 |

However, illnesses in multistate Listeria outbreaks were more severe: overall, 94% of people were hospitalized and 16% died, compared to 33% of people hospitalized and 0.3% of people who died in multistate Salmonella outbreaks and 39% of people hospitalized and 0.65% of people who died in multistate STEC outbreaks.

Figure 6: Percent of Ill People Hospitalized in Solved Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks, by Pathogen

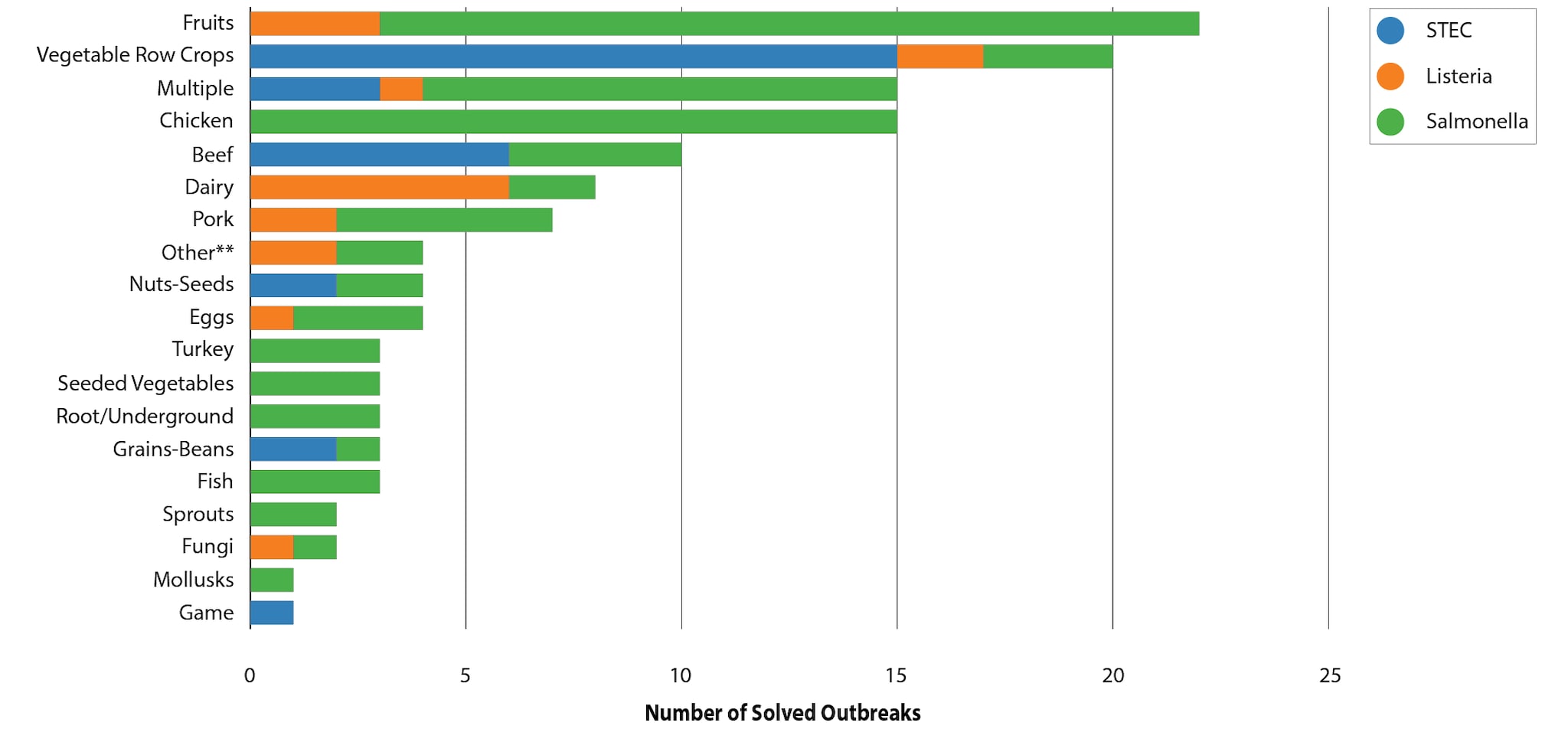

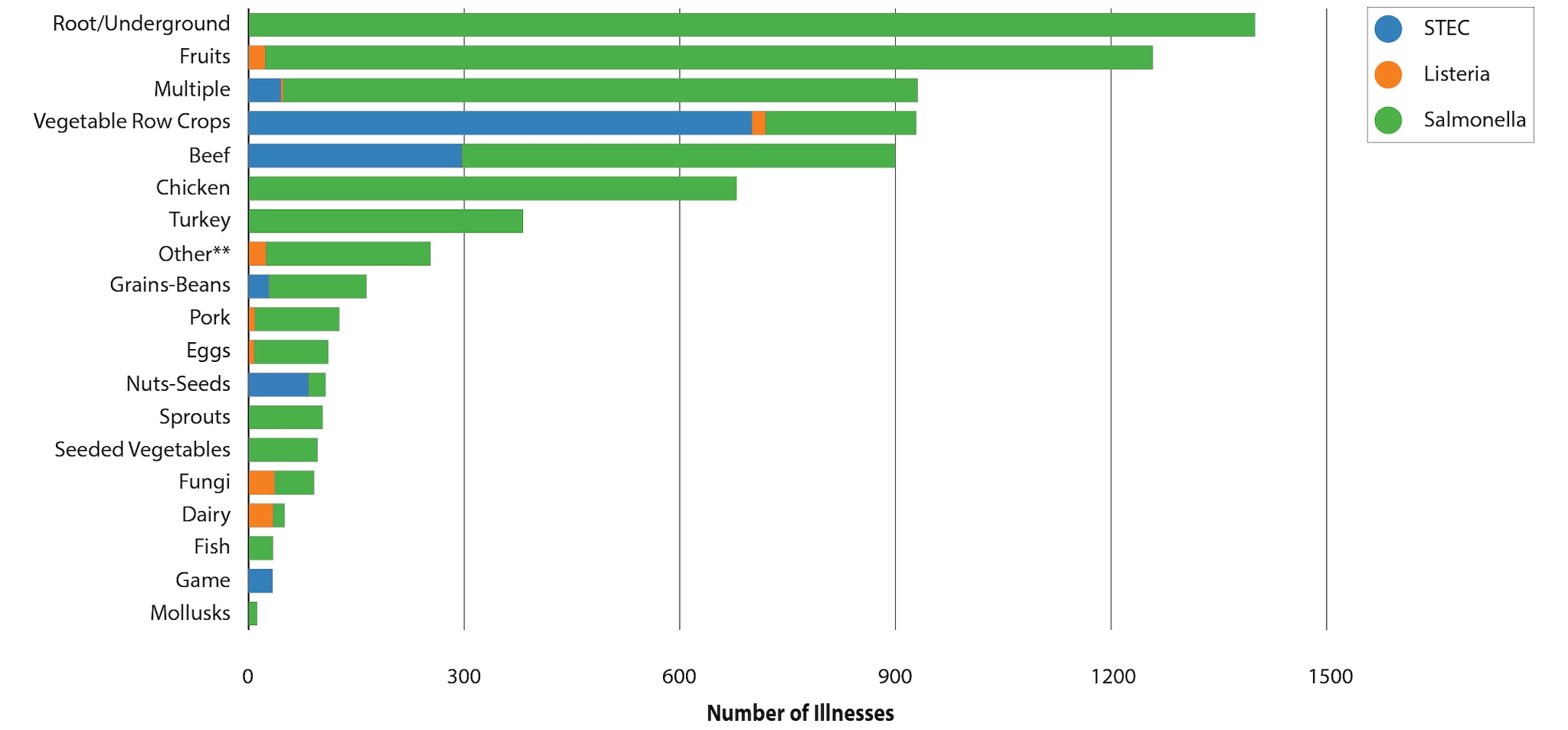

Specific foods linked to outbreaks were grouped into general food categories based on the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (IFSAC) categorization scheme. Fruits were identified as the source of the most solved multistate foodborne outbreaks (22) during 2017–2020. The fruits most linked to multistate outbreaks were papayas (6) and melons (6). Vegetable row crops, such as leafy green vegetables, were the second most common source of multistate foodborne outbreaks (20); romaine was the most common specific leafy green implicated in multistate outbreaks (7). Although root/underground vegetables were the source of just three multistate outbreaks, all confirmed or suspected to be linked to onions, these outbreaks resulted in the most outbreak-associated illnesses (1,400) of any food category. At least one multistate outbreak linked to beef, chicken, dairy, fruits, and vegetable row crops occurred every year during 2017–2020.

Figure 7: Solved Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks by Food Category, 2017–2020

**The “Other” category includes foods or other items (such as dietary supplements) that do not fit into one of the other categories listed.

Figure 8: Number of Illnesses Associated with Solved Multistate Foodborne Outbreaks, by Food Category, 2017–2020

**The “Other” category includes foods or other items (such as dietary supplements) that do not fit into one of the other categories listed.

Multistate Outbreaks Linked to Animal Contact

Of the 199 solved multistate outbreaks, 67 were linked to contact with animals. These multistate outbreaks were associated with 5,081 illnesses, 1,057 hospitalizations, and 8 deaths. Salmonella caused all but one multistate outbreak, which was caused by STEC. During 2017–2020, investigators solved 11–23 animal contact–associated multistate outbreaks each year.

The proportion of sick children younger than 5 was higher for solved multistate animal contact outbreaks (25%) than for solved multistate foodborne outbreaks (9%).

Sick people in multistate outbreaks linked to animal contact ranged in age from less than 1 to 101 years, with a median age of 31 years; 25% of illnesses occurred in children younger than 5, and 14% occurred in adults aged 65 and older. The proportion of sick children younger than 5 was higher for solved multistate animal contact outbreaks (25%) than for solved multistate foodborne outbreaks (9%). Fifty-seven percent were female. Among all multistate animal contact outbreaks, the median percentage of people hospitalized per outbreak was 28%, with a range of 0 to 179 people hospitalized.

Figure 10: Total Number of Illnesses from Multistate Animal Contact Outbreaks Linked to Backyard Poultry 2017–2020

Specific animals linked to outbreaks were grouped into general categories based on the Animal Contact Outbreak Surveillance System (ACOSS). Multistate outbreaks, illnesses, and hospitalizations linked to contact with backyard poultry outnumbered those linked to all other animal sources combined. Contact with backyard poultry caused 50 outbreaks, 4,411 outbreak-associated illnesses, and 870 hospitalizations during 2017–2020. Backyard poultry, such as chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys, can carry Salmonella even if they look healthy, appear clean, and show no signs of illness. Contact with backyard poultry is an established risk factor for transmission of Salmonella due to direct contact with birds or contact with their environment.

Figure 11: Proportion of Solved Multistate Salmonella Animal Contact Outbreaks, by Animal Contact Category

Figure 12: Proportion of Illnesses in Solved Multistate Salmonella Animal Contact Outbreaks, by Animal Contact Category

Turtles were the source of five multistate animal contact outbreaks, causing the second highest number of outbreak-associated illnesses (232) and hospitalizations (76). Children under the age of five years accounted for 34% of the illnesses associated with these outbreaks. All five outbreaks were linked specifically to small turtles (shell length <4 inches). People can get sick from Salmonella by eating food or touching their mouth after touching turtles or the areas where they live and roam. Small turtles are illegal to sell in the United States because they are likely to cause Salmonella infection and because of the number of illnesses they cause and the risk to children who are most likely to have severe Salmonella infections.

Figure 13: Animal Contact Category Dashboard, 2017–2020

Table 3: Confirmed and Suspected Sources and Pathogens by Animal Category

Outbreaks Linked to Other Sources

Two multistate outbreaks were linked to exposure to a Salmonella strain used in various clinical, commercial, and teaching microbiology laboratories. These outbreaks are a reminder of the need to follow biosafety practices while working in laboratories, including not eating or drinking while in the laboratory and use of proper handwashing.

Methods

The data sources and methods used for the analyses in this summary have been previously described in detail in the MMWR report “Summary of Possible Multistate Enteric (Intestinal) Disease Outbreaks in 2016.” The methods used to classify a possible multistate outbreak, outbreak strain, outbreak-related case, outbreak, solved outbreak, suspected source, and confirmed source are unchanged since that report. Briefly, CDC maintains an internal tracking database (known as the Outbreak Management System, OMS) of investigations coordinated by CDC of possible multistate outbreaks caused by Salmonella, STEC, and L. monocytogenes. These analyses were based on data in OMS, with additional information from PulseNet (for patient age information), the Animal Contact Outbreak Surveillance System (ACOSS) for outbreaks of human enteric illness linked to contact with animals or their environments, and the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System (FDOSS), which supplied food category information when a confirmed or suspected food source was identified.

Several changes affecting this summary compared to the MMWR report covering 2016 investigations are as follows:

- An investigation of a possible multistate outbreak was included in this report if it began on or after January 1, 2017, and ended on or before March 31, 2021, or if it began before 2017 but ended during April 1, 2017–March 31, 2021.

- The investigation was considered to have occurred in the year it was identified if it began during that year and ended on or before March 31 of the following year; otherwise, if the investigation ended after March 31 of the following year, it was categorized as occurring in the year that the investigation ended.

- Before July 2019, PulseNet used pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) for detection of possible outbreaks of Salmonella and STEC. In July 2019, PulseNet transitioned to using whole genome sequencing for cluster detection for Salmonella and STEC. WGS has been the primary method of cluster detection for Listeria since late 2013. Implementation of WGS in 2019 likely supported CDC’s ability to continue to detect possible outbreaks despite the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on public health surveillance.

- One limitation of this summary is that the number of Listeria investigations reported may be an underestimate, as investigations of certain Listeria strains were re-opened more than once before a vehicle was identified. Data reported in OMS for listeriosis outbreaks, including case counts and duration, represent the status of the outbreak at the time the most recent investigation was closed.

- The number of outbreaks reported here may differ from the number of outbreaks reported in FDOSS, which includes both single state and multistate outbreaks and a larger group of pathogens. In rare circumstances the year assigned to an outbreak might differ between FDOSS and this report.

- For a detailed description of the definitions, data sources, methods used, and additional limitations, please see the MMWR for the 2016 summary .

Acknowledgements

This work would not be possible without the collaboration and critical work of many partners, including local, state, and territorial health and agriculture departments; the PulseNet database team, CDC; the Outbreak Response and Prevention Branch (ORPB), CDC; Food and Drug Administration Coordinated Outbreak Response and Evaluation Network, Washington, DC; and U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Office of Public Health Science, Applied Epidemiology Staff, Washington, DC. We would like to also acknowledge Kaylea Nemechek, Maria Sanchez, Kate Marshall, and Karen Neil (ORPB) for their efforts on this summary.