Racism

Indicator Profile

Race is a social construct that divides people into categories based on nationality, ethnicity, phenotype, or other markers of social differences.1 Racism, defined as an organized social system that devalues and disempowers racial groups regarded as inferior; reduces access to resources and opportunities such as employment, housing, education, and health care; and increases exposure to risk factors.2,3 Research has consistently shown that racism drives racial/ethnic inequities in cardiovascular disease (CVD).4,5 According to the American Heart Association (AHA), people of color—including people who are Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian—experience varying degrees of social disadvantage that puts these groups at increased risk of CVD and contributes to inequities in CVD outcomes.6

Indicators

This document provides guidance for measuring six indicators related to racism that influence inequities across various social and environmental factors, leading to differential risks for developing CVD or differential access to and receipt of health care. The six racism indicators are measured at different levels of analysis, including individual, census tract, city, county, metropolitan area, and state.

Immigration Status

Why is this indicator relevant?

Immigration status, which refers to the way in which a person resides in the United States or has the authority to reside in the United States, has been linked to health inequities.7 Although immigration status does not equate to race, non-White immigrants are susceptible to racial profiling, discrimination, and anti-immigrant sentiment, which in turn contributes to psychological stress and increases the risk of negative health outcomes.8 Immigrant families, especially those who lack documentation, often lack health care resources such as insurance or a primary care physician; this may be related to attempts to avoid negative interactions with federal agencies.9 Immigrants often struggle with discrimination, language barriers, low income, and other socioeconomic challenges.

Studies suggest that foreign-born adults who reside in the United States have lower prevalence of CVD risk factors, lower incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease, and lower CVD mortality rates than those born in the United States.10,11 However, evidence also suggests that the protective effect of foreign birthplace on cardiovascular health decreases with increasing length of residency in the United States.12,13,14

Acculturation, or the adoption of behavioral and social norms, is associated with poorer health behaviors and social isolation due to erosion of cultural and familial ties. Undocumented individuals face challenges in accessing care due to exclusion from public insurance programs and employer-based insurance, challenges that may affect CVD prevention, treatment, and management.15 Immigrants are also prone to higher levels of acculturative stress and chronic stress, which are risk factors for CVD.16,17

South Asians (people from Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) comprise one-quarter of the world’s population and are one of the fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States. Compared with other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, South Asians have a higher atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk and higher proportional mortality rate from ischemic heart disease.18 The risk, treatment, and outcomes of ASCVD among South Asians also vary by country of residence. Despite sharing the same genetic risk factors as South Asians living in their native countries, South Asians in the United States have different CVD outcomes, likely due to acculturation’s impact on health behaviors and to variations in socioeconomic status, education, health attitudes, and health insurance.19

Although studies have shown that recent Hispanic/Latino immigrants have better CVD outcomes than U.S.-born Hispanic/Latino adults, increasing duration of residency is associated with worsening CVD risk factors among Hispanic/Latino immigrants due to increased exposure to poorer diets, sedentary lifestyle, and increased stress and substance use.20,21 Hispanic/Latino noncitizens face systemic barriers to accessing care, including difficulty in obtaining essential medications such as statins (lipid-lowering agents) that are critical for CVD prevention. A study examining the relationship between noncitizen concentration at the neighborhood level and statin nonadherence found that individuals living in neighborhoods with high noncitizen concentrations were more nonadherent to statins than those in Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods with fewer noncitizens.22

This indicator can be assessed by the following measure. Click on the measure to learn more:

Race-Consciousness

Why is this indicator relevant?

Race-consciousness reflects awareness and consciousness of stereotypes associated with one’s race/ethnicity, which may also result in heightened stress associated with the anticipation of experiencing racial bias, prejudice, or discrimination. Studies suggest that experiencing discrimination may be associated with greater race consciousness and that the anticipatory vigilance of race-consciousness has been linked to negative health outcomes such as lower self-reported overall health, poorer self-reported medication adherence, less sleep, and hypertension.23,24

Several studies document that Black/African American patients report more race-consciousness than White patients. Among Black/African American persons, race-consciousness was associated with higher diastolic blood pressure and hypertension.25,26

Race-consciousness reflects awareness and consciousness of stereotypes associated with one’s own race/ethnicity, which may also result in heightened stress associated with the anticipation of experiencing racial bias, prejudice, or discrimination. This indicator can be assessed by the following measures. Click on each measure to learn more:

Racial Income Gap

Why is this indicator relevant?

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, it became illegal for employers to discriminate based on race.28 Although the Civil Rights Act eliminated many legally sanctioned (de jure) forms of discrimination, many persist, including in hiring and promotion practices. Such experiences contribute to racial/ethnic inequities in income, particularly the racial income gap (RIGap), which is the difference in median income between racial and ethnic groups.29

The United States has seen a rise in racial income inequality in recent decades, with wealth inequality following a similar trend.30 For instance, in 2019, the median income for Black/African American households was roughly 60% of the median income for White households. Furthermore, the median White family had eight times the wealth of the median Black/African American family and five times the wealth of the median Hispanic/Latino family.31 Another study found that Black/African American persons earned about 38% less than White persons did.32 Research suggests that factors such as educational inequality, unemployment differences, and government policies contribute to the RIGap.33 Furthermore, racial income inequality has had adverse societal and health consequences, including racial disparities in health care and homeownership, as well as increases in violent crime and suicide.34 One study observed that higher levels of RIGap at the ZIP-code level were associated with high levels of perceived discrimination, behavioral avoidance, and anxiety.35 Other studies reported that aggregated measures of income equality demonstrated a relationship with health outcomes such as mortality, self-rated health, and risk of coronary heart disease, with the strongest effects observed between county and state levels of income inequality and individual health.36,37

Several studies suggest that substantial disparities in CVD prevalence exist between the highest-resourced groups and the remainder of the population.38,39,40 County-level measures of median income and income inequality are also associated with county- and individual-level CVD mortality rates.41,42 Racial income inequality may affect CVD risk through several pathways, including environmental, occupational, and neighborhood exposures affecting psychosocial, metabolic, and behavioral risk factors for CVD.43,44,45,46 The chronic stress due to social dysfunction in unequal communities may result in heightened blood pressure (BP), leading to the adoption of unhealthy coping behaviors (e.g., smoking, unhealthy eating, alcohol consumption), which can affect cardiovascular and other chronic diseases.47,48,49,50 Additionally, income inequality is associated with increased crime.51,52 Perceived lack of safety from increased crime may lead to reduced outdoor physical activity, leading to increased body mass index, increased BP, and other risk factors for CVD.53 Moreover, income disparities are linked to poor access to care, and people in lower-income groups are less likely to utilize preventive services for CVD.54

The racial income gap refers to the differences in median income between racial and ethnic groups. This indicator can be assessed by the following measures. Click on each measure to learn more:

Racial Residential Segregation

Why is this indicator relevant?

Racial residential segregation refers to the physical separation of races in residential settings and serves as a proxy for structural racism due to the systematic disinvestment of neighborhoods among historically marginalized groups that occurs along with segregation.60,61 Racial residential segregation and its systematic disinvestments have negative economic, educational, employment, and environmental consequences that lead to systematic discrimination in housing and lending and ultimately affect downstream health outcomes. On average, individuals from historically marginalized groups—particularly Black/African American persons, Hispanic/Latino persons, and American Indian/Alaska Native persons, are more likely to have lower high school graduation rates, to have individual and household incomes below the federal poverty level (annual income thresholds set by the federal government to determine financial eligibility criteria62), and to lack insurance and regular access to quality primary care due to structural racism resulting from residential segregation.63

Research suggests that concentrated poverty, poor housing environments, and inequitable access to health care and education are key pathways through which racial residential segregation affects cardiovascular outcomes and that the socioeconomic factors associated with segregation can explain more of the disparities in CVD mortality than traditional cardiovascular risk factors can.64 Using data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Kershaw et al. found that Black/African American people living in neighborhoods (defined by census tracts) segregated from other racial/ethnic groups are at greater risk for CVD than Black/African American persons living in more racially/ethnically integrated neighborhoods. Kershaw et al. found the reverse relationship for White persons—that is, White persons living in less integrated neighborhoods had better cardiovascular outcomes.65 However, this effect disappeared after adjusting for neighborhood poverty.66 No effects were observed for Hispanic/Latino Americans. In a later review of the literature, Kershaw and Albrecht reported that this pattern held among most studies examining the effects of neighborhood (census-tract) and metropolitan-level segregation on CVD risk, especially among Black/African American individuals.67

Racial residential segregation refers to the physical separation of races in residential settings and serves as a proxy for structural racism due to the systematic disinvestment of neighborhoods among historically marginalized groups that occurs along with segregation. This indicator can be assessed by the following measures. Click on each measure to learn more:

Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Trauma

Why is this indicator relevant?

Racial/ethnic discrimination is defined as any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on race, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, or any other field of public life.75 The anticipation and experience of racial/ethnic discrimination have been linked to negative health behaviors and outcomes such as increased substance use and abuse, elevated stress, less sleep, and increased depressive symptoms.76,77,78

Relating to cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes, past research has found robust and consistent associations between reports of discrimination and ambulatory blood pressure (BP).79 For example, exposure to racial/ethnic discrimination across the life course is associated with elevated BP in Black/African American persons and Hispanic/Latino adults.80 One probable pathway is that racial discrimination can lead to both acute and chronic stress responses within multiple physiological systems. Specifically, exposure to discrimination results in increases in heart rate and BP that, with repeated exposure over time, can result in increased risk for hypertension and coronary artery calcification.81 However, findings in this area of research have been inconsistent; other studies find no association between racial/ethnic discrimination and CVD outcomes.

Racial trauma, or race-based traumatic stress, refers to the mental and emotional injury caused by encounters with racial bias and ethnic discrimination, racism, and hate crimes.82 Trauma is distinct from experiences of discrimination in that it captures events that are extreme, overwhelming, and horrific in impact.83 Victims of trauma can experience both short- and long-term adverse physiological effects, because the brain has been shown to react to and sometimes retain the resulting emotions and trauma.84 For instance, racial trauma has been shown to affect individuals’ health behaviors and psychosocial factors, such as the amount of stress and sleep health, which directly affect neurobiological mediators, such as the cardiovascular system, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis, brain systems, and the immune system. These neurobiological mediators ultimately lead to an increased risk for CVD.85

Racial/ethnic discrimination is defined as any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on race, descent, or national or ethnic origin with the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, or any other field of public life. This indicator can be assessed by the following measures. Click on each measure to learn more:

Redlining

Why is this indicator relevant?

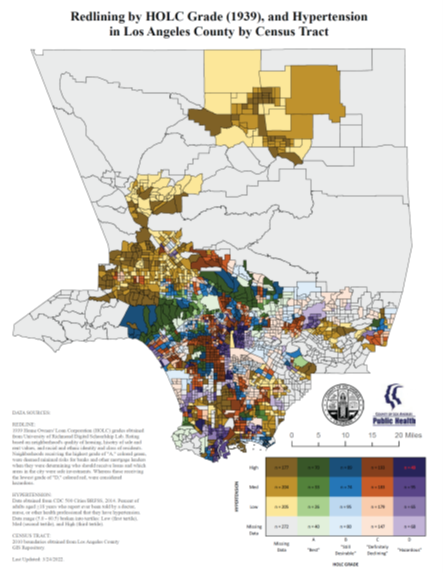

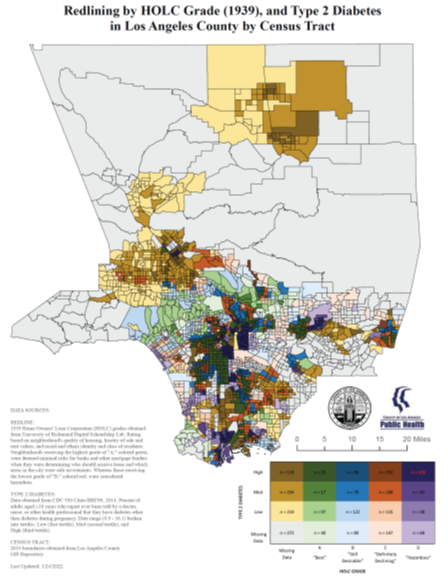

Historical redlining was the practice of systematically designating areas with higher numbers of Black/African American persons, immigrants, and working-class residents as “hazardous.”92 This practice was enacted by the Federal Housing Administration in the 1930s and led to institutionalized discriminatory lending practices that denied mortgages in diverse and working-class neighborhoods.92 Ultimately, historical redlining resulted in disinvestment, poverty concentration, White flight, and further racial residential segregation. Since its inception, the definition of redlining has evolved to encapsulate discriminatory housing practices more broadly. The contemporary definition of redlining refers to the systematic denial of services to residents of certain neighborhoods or communities associated with a certain racial/ethnic group.93

Although the historical practice of redlining was abolished in 1968, communities in historically redlined areas are still socioeconomically disadvantaged and more likely to have a higher concentration of Blacks/African American residents. Historical redlining has also had a measurable impact on health outcomes. Residence in historically redlined areas is associated with worse physical and mental health, as well as higher prevalence of adverse outcomes after inpatient hospitalization, post-operative mortality, pre-term births, gunshot-related injuries, asthma, heat-related illness (i.e., urban heat island effect), and chronic conditions.94

According to ecosocial theory, which describes how multiple levels of influence impact the distribution of disease in populations, redlining may drive disparities in CVD risk and outcomes.95,96,97 Social, environmental, economic, and biologic factors interact to affect physiological, metabolic, and cardiovascular systems.98 Indeed, a recent study finds that Black/African American adults residing in historically redlined areas are more likely to have lower cardiovascular health scores across seven CVD risk factors.99

The contemporary definition of redlining refers to the systematic denial of services to residents of certain neighborhoods or communities associated with a certain racial/ethnic group. This indicator can be assessed by the following measures. Click on each measure to learn more:

Case Example

This case example was developed from the Health Equity Indicators (HEI) Pilot Study. Seven health care organizations participated in the HEI Pilot Study from January 2022 to April 2022 to pilot-test a subset of HEIs in order to assess the feasibility of gathering and analyzing data on these indicators within health care settings. The pilot case examples document participating sites’ experiences with data collection and lessons learned from piloting the HEIs.

Field Note

These field notes showcase other examples of health equity measurement and evaluation at health care organizations, such as health departments. It is important to note that the examples in the field notes are not derived from the HEI Pilot Study and therefore may reflect slightly different uses or definitions of HEIs. In some cases, the HEIs presented in the field notes may not perfectly align with the measurement definition and guidance provided in the HEI Profiles.

References

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

- Brewer LC, Cooper LA. Race, discrimination, and cardiovascular disease. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(6):270–4. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.06.stas2-1406

- Mody P, Gupta A, Bikdeli B, Lampropulos JF, Dharmarajan K. Most important articles on cardiovascular disease among racial and ethnic minorities. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(4):e33–41. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967638

- Javed Z, Haisum Maqsood M, Yahya T, Amin Z, Acquah I, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15(1):e007917. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.007917

- Esperanza United. What Is Immigration Status? Accessed July 21, 2022. https://esperanzaunited.org/en/knowledge-base/content-type/what-is-immigration-status/

- Skolarus LE, Sharrief A, Gardener H, Jenkins C, Boden-Albala B. Considerations in addressing social determinants of health to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in stroke outcomes in the United States. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3433–9.

- Cabral J, Cuevas AG. Health inequities among Latinos/Hispanics: Documentation status as a determinant of health. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(5):874–9. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00710-0

- Lê-Scherban F, Albrecht SS, Bertoni A, Kandula N, Mehta N, Diez Roux AV. Immigrant status and cardiovascular risk over time: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(6):429–35.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.04.008

- Fang J, Yuan K, Gindi RM, Ward BW, Ayala C, Loustalot F. Association of birthplace and coronary heart disease and stroke among U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006 to 2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(7):e008153. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008153

- Lê-Scherban F, Albrecht SS, Bertoni A, Kandula N, Mehta N, Diez Roux AV. Immigrant status and cardiovascular risk over time: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(6):429–35.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.04.008

- Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(7):593–625. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071

- Shaw PM, Chandra V, Escobar GA, Robbins N, Rowe V, Macsata R. Controversies and evidence for cardiovascular disease in the diverse Hispanic population. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(3):960–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.111

- Cabral J, Cuevas AG. Health inequities among Latinos/Hispanics: Documentation status as a determinant of health. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(5):874–9. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00710-0

- Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(7):593–625. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071

- Volgman AS, Palaniappan S, Aggarwal NT, Gupta M, Khandelwal A, Krishnan AV, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 138(1):e1–34.

- Volgman AS, Palaniappan S, Aggarwal NT, Gupta M, Khandelwal A, Krishnan AV, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 138(1):e1–34.

- Volgman AS, Palaniappan S, Aggarwal NT, Gupta M, Khandelwal A, Krishnan AV, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in South Asians in the United States: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatments: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 138(1):e1–34.

- Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(7):593–625. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071

- Shaw PM, Chandra V, Escobar GA, Robbins N, Rowe V, Macsata R. Controversies and evidence for cardiovascular disease in the diverse Hispanic population. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(3):960–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.111

- Guadamuz JS, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Daviglus ML, Calip GS, Nutescu EA, Qato DM. Statin nonadherence in Latino and noncitizen neighborhoods in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, 2012–2016. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(4):e263–78. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2021.01.032

- James D. The seemingly ‘protective’ effect of internalised racism on overall health among 780 Black/African Americans: The serial mediation of stigma consciousness and locus of control. Psychol Health. 2021;36(4):427–43.

- Orom H, Sharma C, Homish GG, Underwood W, Homish DL. Racial discrimination and stigma consciousness are associated with higher blood pressure and hypertension in minority men. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017;4(5):819–26. doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0284-2

- Orom H, Sharma C, Homish GG, Underwood W, Homish DL. Racial discrimination and stigma consciousness are associated with higher blood pressure and hypertension in minority men. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2017;4(5):819–26. doi:10.1007/s40615-016-0284-2

- Brewer LC, Carson KA, Williams DR, Allen A, Jones CP, Cooper LA. Association of race consciousness with the patient–physician relationship, medication adherence, and blood pressure in urban primary care patients. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(11):1346–52. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpt116

- Clark R, Benkert RA, Flack JM. Large arterial elasticity varies as a function of gender and racism-related vigilance in black youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(4):562-569. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.012

- National Archives. Civil Rights Acts (1964). Updated February 8, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/civil-rights-act

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- National Archives. Civil Rights Acts (1964). Updated February 8, 2022. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/civil-rights-act

- Bhutta N, Andrew CC, Lisa JD, and Joanne WH. Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. FEDS Notes. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; September 28, 2020.

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:78–91. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxh003

- Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Gilman SE. U.S. state-level income inequality and risks of heart attack and coronary risk behaviors: Longitudinal findings. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(5):573–88. doi:10.1007/s00038-015-0678-7

- Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:78–91. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxh003

- He J, Zhu Z, Bundy JD, Dorans KS, Chen J, Hamm LL. Trends in cardiovascular risk factors in U.S. adults by race and ethnicity and socioeconomic status, 1999–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1286–98. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.15187

- Abdalla SM, Yu S, Galea S. Trends in cardiovascular disease prevalence by income level in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2018150. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18150

- Khatana SAM, Venkataramani AS, Nathan AS, Dayoub EJ, Eberly LA, Kazi DS, et al. Association between county-level change in economic prosperity and change in cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged U.S. adults. JAMA. 2021;325(5):445–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26141

- Massing MW, Rosamond WD, Wing SB, Suchindran CM, Kaplan BH, Tyroler HA. Income, income inequality, and cardiovascular disease mortality: relations among county populations of the United States, 1985 to 1994. South Med J. 2004;97(5):475–84. doi:10.1097/00007611-200405000-00012

- Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:78–91. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxh003

- Kim D, Kawachi I, Hoorn SV, Ezzati M. Is inequality at the heart of it? Cross-country associations of income inequality with cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1719–32. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.030

- Diez-Roux AV, Link BG, Northridge ME. A multilevel analysis of income inequality and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:673–87. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00320-2

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and social dysfunction. Ann Rev Sociol. 2009;35:493–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115926

- Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Gilman SE. U.S. state-level income inequality and risks of heart attack and coronary risk behaviors: Longitudinal findings. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(5):573–88. doi:10.1007/s00038-015-0678-7

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo K, Kawachi I. Use of the Yitzhaks index as a test of relative deprivation for health outcomes: A review of recent literature. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:129–37. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.004

- Diez Roux AV. Residential environments and cardiovascular risk. J Urban Health. 2003;80:569–89. doi:10.1093/jurban/jtg065

- Kubzansky LD, Seeman TE, Glymour MM. Biological pathways linking social conditions and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2014:512–61.

- Elgar FJ, Aitken N. Income inequality, trust, and homicide in 33 countries. Eur J Pub Health. 2011;21:241–6. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq068

- Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Harper S, Hillemeier M, Ross N, Kaplan GA, Wolfson M. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q. 2004;82:5–99. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00302.x

- Diez-Roux AV, Link BG, Northridge ME. A multilevel analysis of income inequality and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:673–87. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00320-2

- Shahu A, Okunrintemi V, Tibuakuu M, Khan SU, Gulati M, Marvel F, et al. Income disparity and utilization of cardiovascular preventive care services among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021;8:100286. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100286

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302955

- Krieger N, Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Coull BA, Hemenway D. Local residential segregation matters: Stronger association of census tract compared to conventional city-level measures with fatal and non-fatal assaults (total and firearm related), using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for racial, economic, and racialized economic segregation, Massachusetts (US), 1995–2010. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):244–58. doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0116-z

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16. doi:10.1093/phr/116.5.40

- Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, et al. Call to Action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–68. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936

- HealthCare.gov. Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Accessed June 21, 2022. https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/

- Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, et al. Call to Action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–68. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936

- Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, et al. Call to Action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(24):e454–68. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936

- Kershaw KN, Osypuk TL, Do DP, De Chavez PJ, Diez Roux AV. Neighborhood-level racial/ethnic residential segregation and incident cardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2014;131(2):141–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011345

- Kershaw KN, Osypuk TL, Do DP, De Chavez PJ, Diez Roux AV. Neighborhood-level racial/ethnic residential segregation and incident cardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2014;131(2):141–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011345

- Kershaw KN, Albrecht SS. Racial/ethnic residential segregation and cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2015;9(3):10.

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302955

- Krieger N, Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Coull BA, Hemenway D. Local residential segregation matters: Stronger association of census tract compared to conventional city-level measures with fatal and non-fatal assaults (total and firearm related), using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for racial, economic, and racialized economic segregation, Massachusetts (US), 1995–2010. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):244–58. doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0116-z

- Krieger N, Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Coull BA, Hemenway D. Local residential segregation matters: Stronger association of census tract compared to conventional city-level measures with fatal and non-fatal assaults (total and firearm related), using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for racial, economic, and racialized economic segregation, Massachusetts (US), 1995–2010. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):244–58. doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0116-z

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, et al. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi:10.1002/mpr.177

- United Nations. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. Accessed June 3, 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-elimination-all-forms-racial

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

- Jackson CL, Powell-Wiley TM, Gaston SA, Andrews MR, Tamura K, Ramos A. Racial and ethnic disparities in sleep health and potential intervention among women in the United States. J Women’s Health. 2020;29(3):435–42.

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

- Lewis TT, Williams DR, Tamene M, Clark CR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8(1):365. doi:10.1007/s12170-013-0365-2

- Beatty M, DL, Waldstein SR, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Schwartz JC, Brondolo E. Lifetime racial/ethnic discrimination and ambulatory blood pressure: The moderating effect of age. Health Psychology. 2016;35(4):333–42. doi:10.1037/hea0000270

- Lockwood KG, Marsland AL, Matthews KA, Gianaros PJ. Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular health disparities: A multisystem review and health neuroscience perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1428(1):170–207.

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, Green CE. Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional training. Traumatology. 2010;16(4):53–62. doi:10.1177/1534765610389595

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Chapter 3: Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Treatment Improvement Protocol Series, No. 57. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, Green CE. Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional training. Traumatology. 2010;16(4):53–62. doi:10.1177/1534765610389595

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

- Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health: How much does stress really matter? Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):95–113. doi:10.1017/S1742058X11000087

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–96.

- Michaels E, Thomas M, Reeves A, Price M, Hasson R, Chae D, Allen A. Coding the Everyday Discrimination Scale: Implications for exposure assessment and associations with hypertension and depression among a cross section of mid-life African American women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(6):577–84.

- Waelde LC, Pennington D, Mahan C, Mahan RB, Kabour M, Marquett RM. Psychometric properties of the Race-Related Events Scale. Psychol Trauma. 2010;2(1):4–11.

- Daniels KP, Valdez Z, Chae DH, Allen AM. Direct and vicarious racial discrimination at three life stages and preterm labor: Results from the African American Women’s Heart & Health Study. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24:1387–95. doi:10.1007/s10995-020-03003-4.

- Richard R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright; 2017.

- Corporate Finance Institute. Redlining. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 2, 2022. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/other/redlining/

- Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, Gill I, Yamoah O, Roche A, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114696. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696

- Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–44. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544

- Lynch EE, Malcoe LH, Laurent SE, Richardson J, Mitchell BC, Meier HCS. The legacy of structural racism: Associations between historic redlining, current mortgage lending, and health. SSM Popul Health. 2021;14:100793. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100793

- Diaz A, O’Reggio R, Norman M, Thumma JR, Dimick JB, Ibrahim AM. Association of historic housing policy, modern day neighborhood deprivation and outcomes after inpatient hospitalization. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):985–91. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005195

- Mujahid MS, Gao X, Tabb LP, Morris C, Lewis TT. Historical redlining and cardiovascular health: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(51):e2110986118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110986118

- Mujahid MS, Gao X, Tabb LP, Morris C, Lewis TT. Historical redlining and cardiovascular health: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(51):e2110986118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110986118

- Rothstein R. The Color of Law A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright; 2017.

- Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, Gill I, Yamoah O, Roche A, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114696. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696

- Gordils J, Sommet N, Elliot AJ, Jamieson JP. Racial income inequality, perceptions of competition, and negative interracial outcomes. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(1):74–87. doi:10.1177/1948550619837003

- Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Income inequality and health: what have we learned so far? Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26(1):78–91. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxh003

- Kim D, Kawachi I, Hoorn SV, Ezzati M. Is inequality at the heart of it? Cross-country associations of income inequality with cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1719–32. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.030

- Diez-Roux AV, Link BG, Northridge ME. A multilevel analysis of income inequality and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(5):673–87. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00320-2

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and social dysfunction. Ann Rev Sociol. 2009;35:493–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115926

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302955

- Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Coull BA, Krieger N. Spatial social polarisation: using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes jointly for income and race/ethnicity to analyse risk of hypertension. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(12):1199–1207. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205728

- Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy004

- U.S. Census Bureau. Historical Income Tables: Households. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html