Facts about Truncus Arteriosus

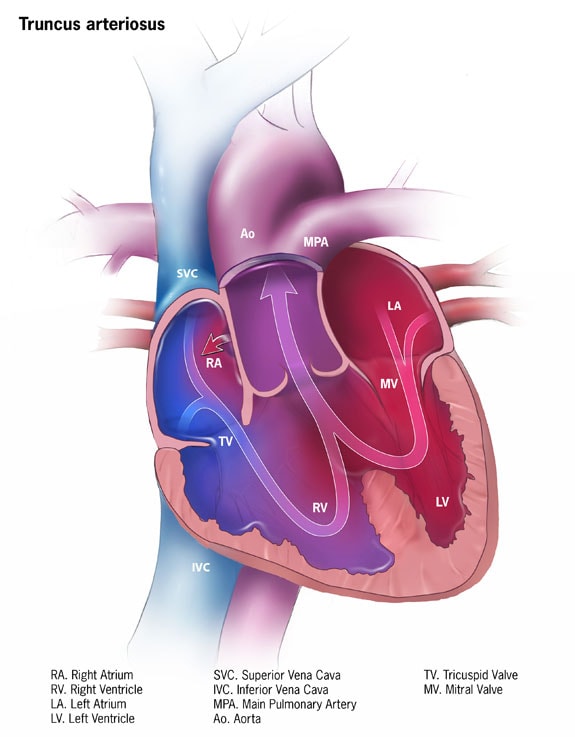

Truncus arteriosus pronounced TRUNG-kus ahr-teer-e-O-sus), also known as common truncus, is a rare defect of the heart in which a single common blood vessel comes out of the heart, instead of the usual two vessels (the main pulmonary artery and aorta).

What is Truncus Arteriosus

Truncus arteriosus is a birth defect of the heart. It occurs when the blood vessel coming out of the heart in the developing baby fails to separate completely during development, leaving a connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery. There are several different types of truncus, depending on how the arteries remain connected. There is also usually a hole between the bottom two chambers of the heart (ventricles) called a ventricular septal defect. Because a baby with this defect may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth, truncus arteriosus is considered a critical congenital heart defect (CCHD). Congenital means present at birth.

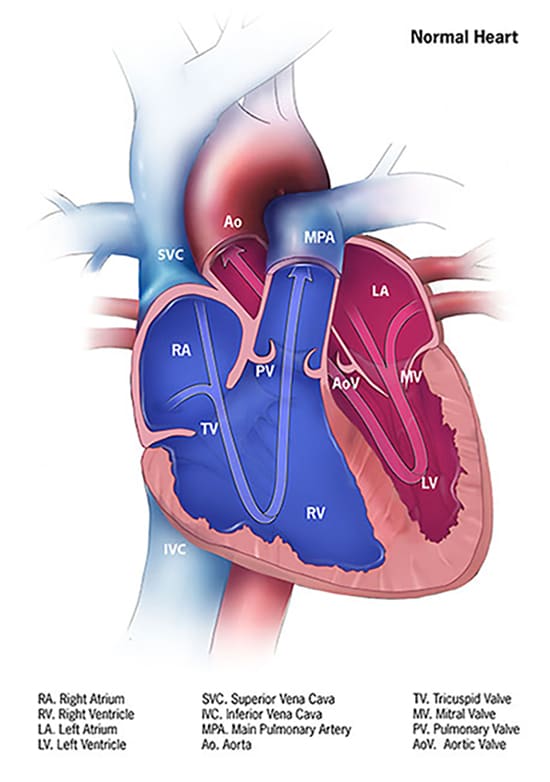

In a baby without a congenital heart defect, the right side of the heart pumps oxygen-poor blood through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. The left side of the heart pumps oxygen-rich blood through the aorta to the rest of the body.

In babies with a truncus arteriosus, oxygen-poor blood and oxygen-rich blood are mixed together as blood flows to the lungs and the rest of the body. As a result, too much blood goes to the lungs and the heart works harder to pump blood to the rest of the body. Also, instead of having both an aortic valve and a pulmonary valve, babies with truncus arteriosus have a single common valve (truncal valve) controlling blood flow out of the heart. The truncal valve is often abnormal. The valve can be thickened and narrowed, which can block the blood as it leaves the heart. It can also leak, causing blood that leaves the heart to leak back into the heart across the valve.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Occurrence

Truncus arteriosus occurs in less than one out of every 10,000 live births. It can occur by itself or as part of certain genetic disorders. There are about 250 cases of truncus arteriosus per year in the United States.1

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of heart defects, such as truncus arteriosus, among most babies are unknown. Some babies have congenital heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. Congenital heart defects are also thought to be caused by the combination of genes and other risk factors such as things the mother comes in contact with in her environment, or what the mother eats or drinks, or certain medications she uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors »

Diagnosis

Truncus arteriosus may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after the baby is born.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, there are screening tests (also called prenatal tests) to check for birth defects and other conditions. Some heart defects might be seen during an ultrasound (which creates pictures of the body). If a health care provider suspects a baby might have truncus arteriosus, the health care provider can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis. A fetal echocardiogram is a more detailed ultrasound of the baby’s heart. This test can show problems with the structure of the heart, like a single large vessel coming from the heart, and how the heart is working with this defect.

After a Baby is Born

Infants with truncus arteriosus usually are in distress in the first few days of life because of the high amount of blood going to the lungs which makes the heart work harder. Infants with truncus arteriosus can have a bluish looking skin color, called cyanosis, because their blood doesn’t carry enough oxygen. Infants with truncus arteriosus or other conditions causing cyanosis can have symptoms such as:

- Problems breathing

- Pounding heart

- Weak pulse

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding

- Extreme sleepiness

If a health care provider suspects a baby might have truncus arteriosus, the health care provider can request an echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis. An echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart, like the single large vessel coming from the heart or misshapen truncal valve. It can also show how the heart is working (or not) with this defect, like if the blood is leaking back into the heart or if it is moving through a hole between the ventricles. Echocardiograms are also useful for helping the doctor follow the child’s health over time.

Truncus arteriosus is a critical congenital heart defect (CCHD) that may be detected with newborn pulse oximetry screening (also known as pulse ox). Pulse oximetry is a simple bedside test to determine the amount of oxygen in a baby’s blood. Low levels of oxygen in the blood can be a sign of a CCHD. Newborn screening using pulse oximetry can identify some infants with a CCHD, like truncus arteriosus, before they show any symptoms.

Treatment

Medications

Some babies with truncus arteriosus also will need medicines to help strengthen the heart muscle, lower their blood pressure, and help their body get rid of extra fluid.

Nutrition

Some babies with truncus arteriosus might become tired while feeding and might not eat enough to gain weight. To make sure babies have a healthy weight gain, a special high-calorie formula might be prescribed. Some babies become extremely tired while feeding and might need to be fed through a feeding tube.

Surgery

Surgery is needed to repair the heart and blood vessels. This is usually done in the first few months of life. Options for repair depend on how sick the child is and the specific structure of the defect. The goal of the surgery to repair truncus arteriosus is to create a separate flow of oxygen-poor blood to the lungs and oxygen-rich blood to the body. Usually, surgery to repair this defect involves the following steps:

- Close the hole between the bottom chambers of the heart (ventricular septal defect) usually with a patch.

- Use the original single blood vessel to create a new aorta to carry oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle out to the body.

- Use an artificial tube (conduit) with an artificial valve to connect the right ventricle to the arteries going to the lungs in order to carry oxygen-poor blood to the lungs.

Most babies with truncus arteriosus survive the surgical repair, but may need more surgery or other procedures as they get older. For example, the artificial tube doesn’t grow, so it will need to be replaced as the child grows. There also may be blockages to blood flow which may need to be relieved, or problems with the truncal valve. Thus, a person born with truncus arteriosus will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist (a heart doctor) to monitor their progress and avoid complications or other health problems.

Reference

- Cara T. Mai, Jennifer L. Isenburg, Mark A. Canfield, Robert E. Meyer, Adolfo Correa, Clinton J. Alverson, Philip J. Lupo, Tiffany Riehle‐Colarusso, Sook Ja Cho, Deepa Aggarwal, Russell S. Kirby. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. BDR Oct 2019.