Facts about Pulmonary Atresia

Pulmonary atresia is a birth defect (pronounced PULL-mun-airy ah-TREE-sha) of the heart where the valve that controls blood flow from the heart to the lungs doesn’t form at all. In babies with this defect, blood has trouble flowing to the lungs to pick up oxygen for the body.

What is Pulmonary Atresia?

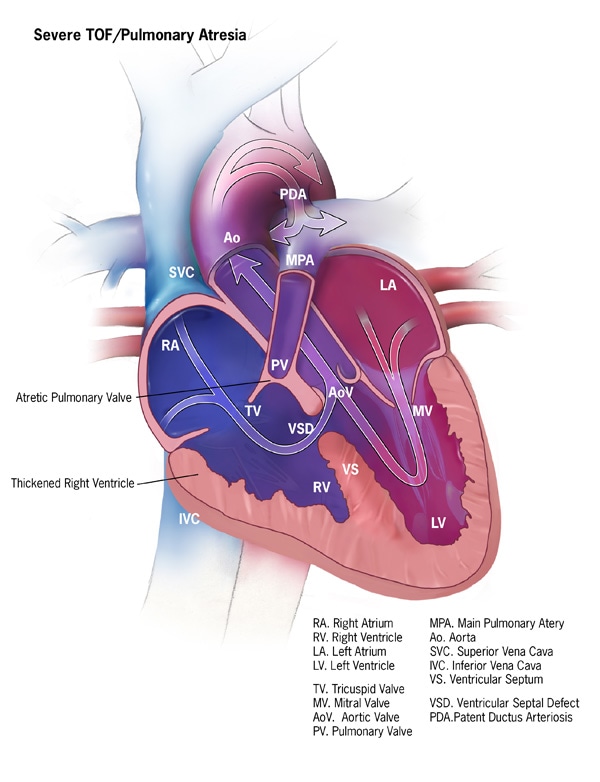

Pulmonary atresia is a birth defect of the pulmonary valve, which is the valve that controls blood flow from the right ventricle (lower right chamber of the heart) to the main pulmonary artery (the blood vessel that carries blood from the heart to the lungs). Pulmonary atresia is when this valve didn’t form at all, and no blood can go from the right ventricle of the heart out to the lungs. Because a baby with pulmonary atresia may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth, this birth defect is considered a critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD). Congenital means present at birth.

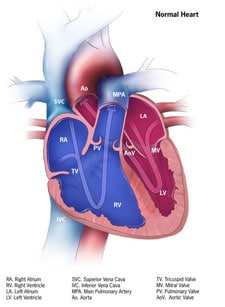

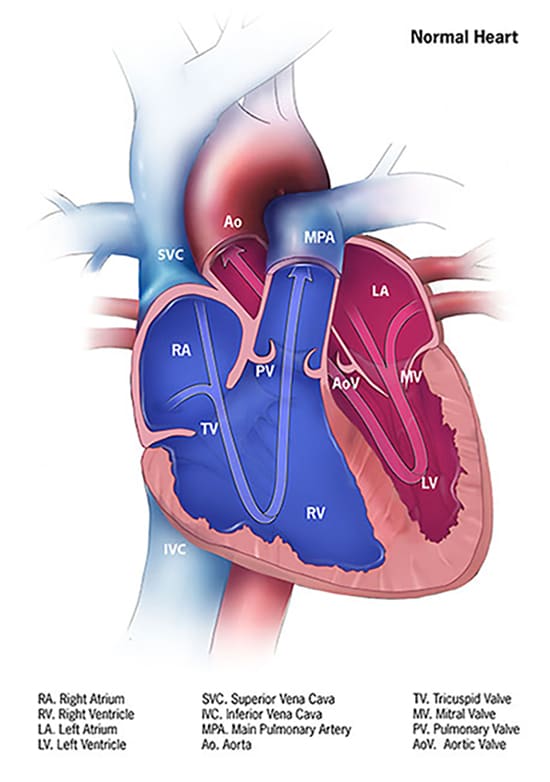

In a baby without a congenital heart defect, the right side of the heart pumps oxygen-poor blood from the heart to the lungs through the pulmonary artery. The blood that comes back from the lungs is oxygen-rich and can then be pumped to the rest of the body. In babies with pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve that usually controls the blood flowing through the pulmonary artery is not formed, so blood is unable to get directly from the right ventricle to the lungs.

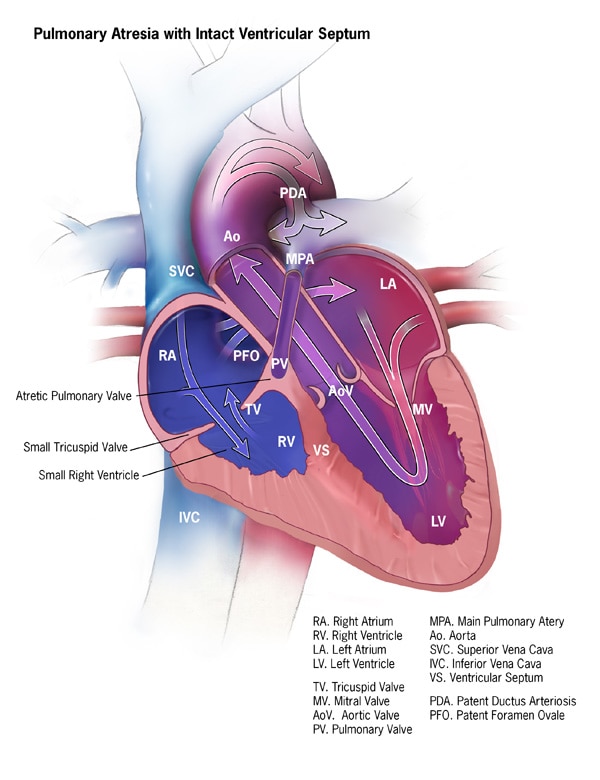

In pulmonary atresia, since blood cannot directly flow from the right ventricle of the heart out to the pulmonary artery, blood must use other routes to bypass the unformed pulmonary valve. The foramen ovale, a natural opening between the right and left upper chambers of the heart during pregnancy that usually closes after the baby is born, often remains open to allow blood flow to the lungs. Additionally, doctors may give medicine to the baby to keep the baby’s patent ductus arteriosus open after the baby’s birth. The patent ductus arteriosus is the blood vessel that allows blood to move around the baby’s lungs before the baby is born and it also usually closes after birth.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Types of Pulmonary Atresia

There are typically two types of pulmonary atresia, according to whether or not a baby also has a ventricular septal defect (a hole in the wall that separates the two lower chambers, or ventricles, of the heart):

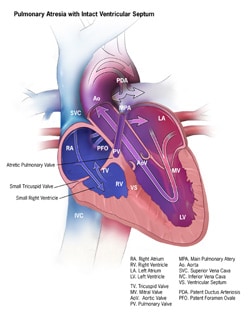

- Pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum: In this form of pulmonary atresia, the wall, or septum, between the ventricles remains complete and intact. During pregnancy when the heart is developing, very little blood flows into or out of the right ventricle (RV), and therefore the RV doesn’t fully develop and remains very small. If the RV is under-developed, the heart can have problems pumping blood to the lungs and the body. The artery which usually carries blood out of the right ventricle, the main pulmonary artery (MPA), remains very small, since the pulmonary valve (PV) doesn’t form.

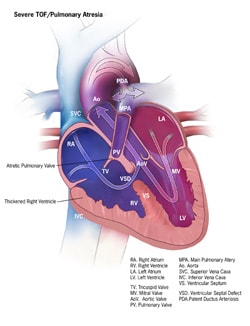

- Pulmonary atresia with a ventricular septal defect: In this form of pulmonary atresia, a ventricular septal defect (VSD) allows blood to flow into and out of the right ventricle (RV). Therefore, blood flowing into the RV can help the ventricle develop during pregnancy, so it is typically not as small as in pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum. Pulmonary atresia with a VSD is similar to another condition called tetralogy of Fallot. However, in tetralogy of Fallot, the pulmonary valve (PV) does form, although it is small and blood has trouble flowing through it – this is called pulmonary valve stenosis. Thus, pulmonary atresia with a VSD is like a very severe form of tetralogy of Fallot.

Occurrence

A 2019 study using 2010-2014 data from birth defects surveillance systems across the United States, researchers estimated that each year about 550 babies in the United States are born with pulmonary atresia. In other words, about 1 in every 7,100 babies born in the United States each year are born with pulmonary atresia.1

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of heart defects, such as pulmonary atresia, among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. Heart defects also are thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other factors, such as the things the mother comes in contact with in the environment, or what the mother eats or drinks, or certain medicines she uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors »

Diagnosis

Pulmonary atresia may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after a baby is born.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, there are screening tests (also called prenatal tests) to check for birth defects and other conditions. Pulmonary atresia might be seen during an ultrasound (which creates pictures of the body). Some findings from the ultrasound may make the healthcare provider suspect a baby may have pulmonary atresia. If so, the healthcare provider can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis. A fetal echocardiogram is an ultrasound specifically of the baby’s heart and major blood vessels that is performed during the pregnancy. This test can show problems with the structure of the heart and how well the heart is working.

After the Baby is Born

Babies born with pulmonary atresia will show symptoms at birth or very soon afterwards. They may have a bluish looking skin color, called cyanosis, because their blood doesn’t carry enough oxygen. Infants with pulmonary atresia can have additional symptoms such as:

- Problems breathing

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding

- Extreme sleepiness

During a physical examination, a doctor can see the symptoms, such as bluish skin or problems breathing. Using a stethoscope, a doctor will check for a heart murmur (an abnormal “whooshing” sound caused by blood not flowing properly). However, it is not uncommon for a heart murmur to be absent right at birth.

If a doctor suspects that there might be a problem, the doctor can request one or more tests to confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary atresia. The most common test is an echocardiogram. This test is an ultrasound of the baby’s heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart, like holes in the walls between the chambers, and any irregular blood flow. Cardiac catheterization (inserting a thin tube into a blood vessel and guiding it to the heart) also can confirm the diagnosis by looking at the inside of the heart and measuring the blood pressure and oxygen levels. An electrocardiogram (EKG), which measures the electrical activity of the heart, and other medical tests may also be used to make the diagnosis.

Pulmonary atresia is a critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD) that may be detected with newborn screening using pulse oximetry (also known as pulse ox). Pulse oximetry is a simple bedside test to estimate the amount of oxygen in a baby’s blood. Low levels of oxygen in the blood can be a sign of a critical CHD. Newborn screening using pulse oximetry can identify some infants with a critical CHD, like pulmonary atresia, before they show any symptoms.

Treatments

Most babies with pulmonary atresia will need medication to keep the ductus arteriosus open after birth. Keeping this blood vessel open will help with blood flow to the lungs until the pulmonary valve can be repaired.

Treatment for pulmonary atresia depends on its severity.

- In some cases, blood flow can be improved by using cardiac catheterization (inserting a thin tube into a blood vessel and guiding it to the heart). During this procedure, doctors can expand the valve using a balloon or they may need to place a stent (a small tube) to keep the ductus arteriosus open.

- In most cases of pulmonary atresia, a baby may need surgery soon after birth. During surgery, doctors widen or replace the pulmonary valve and enlarge the passage to the pulmonary artery. If a baby has a ventricular septal defect, the doctor also will place a patch over the ventricular septal defect to close the hole between the two lower chambers of the heart. These actions will improve blood flow to the lungs and the rest of the body. If a baby with pulmonary atresia has an underdeveloped right ventricle, he or she might need staged surgical procedures, similar to surgical repairs for hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Most babies with pulmonary atresia will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist (a heart doctor) to monitor their progress and check for other health conditions that might develop as they get older. As adults, they may need more surgery or medical care for other possible problems.

References

- Cara T. Mai, Jennifer L. Isenburg, Mark A. Canfield, Robert E. Meyer, Adolfo Correa, Clinton J. Alverson, Philip J. Lupo, Tiffany Riehle‐Colarusso, Sook Ja Cho, Deepa Aggarwal, Russell S. Kirby. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. BDR Oct 2019.