Facts about Ventricular Septal Defect

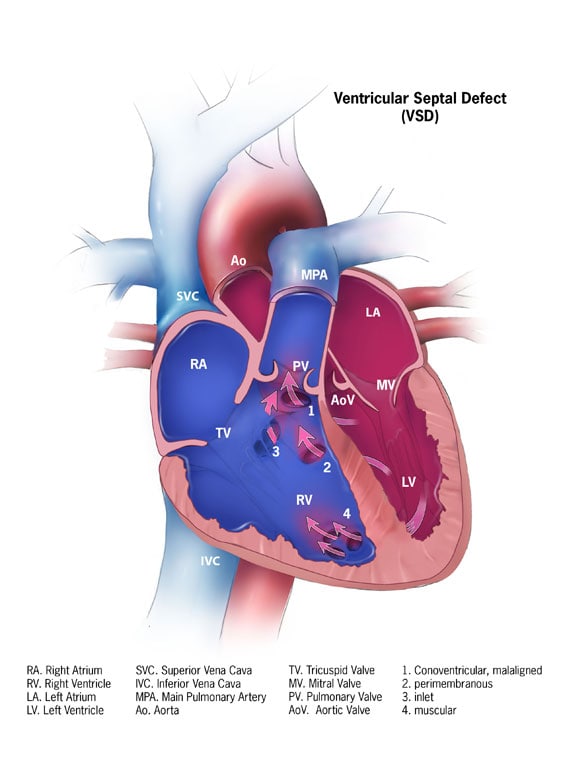

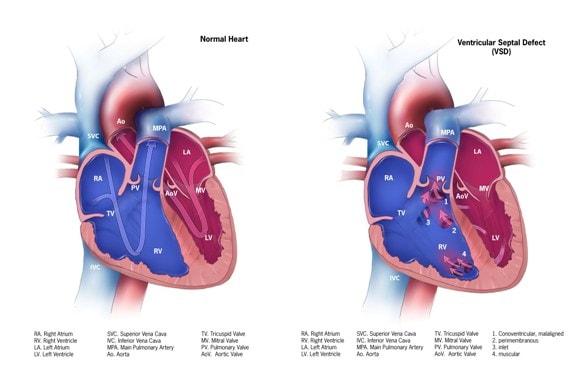

A ventricular septal defect (pronounced ven·tric·u·lar sep·tal de·fect) (VSD) is a birth defect of the heart in which there is a hole in the wall (septum) that separates the two lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart. This wall also is called the ventricular septum.

What is a Ventricular Septal Defect

A ventricular septal defect happens during pregnancy if the wall that forms between the two ventricles does not fully develop, leaving a hole. A ventricular septal defect is one type of congenital heart defect. Congenital means present at birth.

In a baby without a congenital heart defect, the right side of the heart pumps oxygen-poor blood from the heart to the lungs, and the left side of the heart pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body.

In babies with a ventricular septal defect, blood often flows from the left ventricle through the ventricular septal defect to the right ventricle and into the lungs. This extra blood being pumped into the lungs forces the heart and lungs to work harder. Over time, if not repaired, this defect can increase the risk for other complications, including heart failure, high blood pressure in the lungs (called pulmonary hypertension), irregular heart rhythms (called arrhythmia), or stroke.

Learn more about how the heart works »

Types of Ventricular Septal Defects

An infant with a ventricular septal defect can have one or more holes in different places of the septum. There are several names for these holes. Some common locations and names are (see figure):

- Conoventricular Ventricular Septal Defect

In general, this is a hole where portions of the ventricular septum should meet just below the pulmonary and aortic valves. - Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defect

This is a hole in the upper section of the ventricular septum. - Inlet Ventricular Septal Defect

This is a hole in the septum near to where the blood enters the ventricles through the tricuspid and mitral valves. This type of ventricular septal defect also might be part of another heart defect called an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). - Muscular Ventricular Septal Defect

This is a hole in the lower, muscular part of the ventricular septum and is the most common type of ventricular septal defect.

Occurrence

In a study in Atlanta, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 42 of every 10,000 babies born had a ventricular septal defect.1 This means about 16,800 babies are born each year in the United States with a ventricular septal defect. In other words, about 1 in every 240 babies born in the United States each year are born with a ventricular septal defect.

Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of heart defects (such as a ventricular septal defect) among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. Heart defects also are thought to be caused by a combination of genes and other risk factors, such as the things the mother comes in contact with in the environment or what the mother eats or drinks or the medicines the mother uses.

Read more about CDC’s work on causes and risk factors »

Diagnosis

A ventricular septal defect usually is diagnosed after a baby is born.

The size of the ventricular septal defect will influence what symptoms, if any, are present, and whether a doctor hears a heart murmur during a physical examination. Signs of a ventricular septal defect might be present at birth or might not appear until well after birth. If the hole is small, it usually will close on its own and the baby might not show any signs of the defect. However, if the hole is large, the baby might have symptoms, including:

- Shortness of breath,

- Fast or heavy breathing,

- Sweating,

- Tiredness while feeding, or

- Poor weight gain.

During a physical examination the doctor might hear a distinct whooshing sound, called a heart murmur. If the doctor hears a heart murmur or other signs are present, the doctor can request one or more tests to confirm the diagnosis. The most common test is an echocardiogram, which is an ultrasound of the heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart, show how large the hole is, and show how much blood is flowing through the hole.

Treatments

Treatments for a ventricular septal defect depend on the size of the hole and the problems it might cause. Many ventricular septal defects are small and close on their own; if the hole is small and not causing any symptoms, the doctor will check the infant regularly to ensure there are no signs of heart failure and that the hole closes on its own. If the hole does not close on its own or if it is large, further actions might need to be taken.

Depending on the size of the hole, symptoms, and general health of the child, the doctor might recommend either cardiac catheterization or open-heart surgery to close the hole and restore normal blood flow. After surgery, the doctor will set up regular follow-up visits to make sure that the ventricular septal defect remains closed. Most children who have a ventricular septal defect that closes (either on its own or with surgery) live healthy lives.

Medicines

Some children will need medicines to help strengthen the heart muscle, lower their blood pressure, and help the body get rid of extra fluid.

Nutrition

Some babies with a ventricular septal defect become tired while feeding and do not eat enough to gain weight. To make sure babies have a healthy weight gain, a special high-calorie formula might be prescribed. Some babies become extremely tired while feeding and might need to be fed through a feeding tube.

References

- Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Defects in Metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. J Pediatr. 2008;153:807-13.