Hookahs

Hookahs are water pipes that are used to smoke specially made tobacco that comes in different flavors, such as apple, mint, cherry, chocolate, coconut, licorice, cappuccino, and watermelon.1

Although many users think it is less harmful, hookah smoking has many of the same health risks as cigarette smoking.1

Hookah is also called narghile, argileh, shisha, hubble-bubble, and goza.1

Hookahs vary in size, shape, and style.1

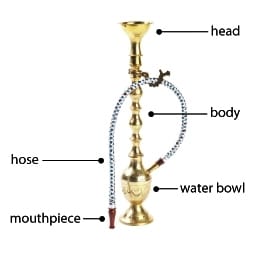

A typical modern hookah has a head (with holes in the bottom), a metal body, a water bowl, and a flexible hose with a mouthpiece.2,3

Hookah smoking is typically done in groups, with the same mouthpiece passed from person to person.1,2,3

Hookah smoking is NOT a safe alternative to smoking cigarettes.1

People who use tobacco should quit all tobacco products to reduce health risks.

- Hookah use began centuries ago in ancient Persia and India.1,2,3

- In 2018, the Monitoring the Future survey found that—4,5

- Nearly 1 in every 13 (7.8%) high school students in the United States had used a hookah to smoke tobacco during the previous year.

- About 1 in every 8 (12.3%) young adults aged 19-30 years had used a hookah to smoke tobacco during the previous year.

- Among 12th graders, annual hookah use increased from nearly 1 in 6 students (17.1%) in 2010 to about 1 in 4 students (22.9%) in 2014, but since that time has decreased sharply to nearly 1 in 13 students (7.8%) in 2018.4

- Monitoring the Future also shows variations in hookah use by region and population density. In 2018, the highest prevalence of use was observed in the Northeast, where 1 in 6 (15.0%) young adults aged 19-30 years had used a hookah to smoke tobacco during the previous year, and in very large cities, where almost 1 in 5 (19.3%) young adults in this age group reported past year use.5

- Other small studies of young adults have found high prevalence of hookah use among college students in the United States. These studies show past-year use ranging from 22% to 40%.6

- New forms of electronic hookah products, including steam stones and hookah pens, have been introduced.

- These products are battery powered and turn liquid containing nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals into an aerosol, which is inhaled.7

- Limited information is currently available on the health risks of electronic tobacco products, including electronic hookahs.7,8

Using a hookah to smoke tobacco poses serious health risks to smokers and others exposed to the smoke from the hookah.

Hookah Smoke and Cancer

- The charcoal used to heat the tobacco can raise health risks by producing high levels of carbon monoxide, metals, and cancer-causing chemicals.1,3

- Even after it has passed through water, the smoke from a hookah has high levels of these toxic agents.3

- Hookah tobacco and smoke contain several toxic agents known to cause lung, bladder, and oral cancers.1,3

- Tobacco juices from hookahs irritate the mouth and increase the risk of developing oral cancers.3,9

Other Health Effects of Hookah Smoke

- Hookah tobacco and smoke contain many toxic agents that can cause clogged arteries and heart disease.1,3

- Babies born to people who smoked water pipes every day while pregnant weigh less at birth (at least 3½ ounces less) than babies born to those who do not smoke.6,10

- Babies born to people who use hookah are also at increased risk for respiratory diseases.9

Hookah Smoking Compared With Cigarette Smoking

- Although many users think it is less harmful, studies have shown that hookah smoke contains many of the same harmful components found in cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, tar, and heavy metals.11,12

- Water pipe smoking delivers nicotine—the same highly addictive drug found in other tobacco products.1

- The tobacco in hookahs is exposed to high heat from burning charcoal, and the smoke is at least as toxic as cigarette smoke.1

- The heat sources used to burn hookah tobacco release other dangerous substances, like carbon monoxide. This may put hookah users at additional risk. 13,14

- Because of the way a hookah is used, people who smoke hookah may absorb more of the toxic substances also found in cigarette smoke than people who smoke cigarettes do.1

- In a typical 1-hour hookah smoking session, users may inhale 100–200 times the amount of smoke they would inhale from a single cigarette. In a single water pipe session, users are exposed to up to 9 times the carbon monoxide and 1.7 times the nicotine of a single cigarette.11,13

- The amount of smoke inhaled during a typical hookah session is about 90,000 milliliters (ml), compared with 500–600 ml inhaled when smoking a cigarette.3

- People who smoke hookah may be at risk for some of the same diseases as cigarette smokers. These include:2,3

- Oral cancer

- Lung cancer

- Stomach cancer

- Cancer of the esophagus

- Reduced lung function

- Decreased fertility

Hookahs and Secondhand Smoke

- Secondhand smoke from hookahs can be a health risk for people who don’t smoke. It contains smoke from the tobacco as well as smoke from the heat source (e.g., charcoal) used in the hookah.1,6,13

Nontobacco Hookah Products

- Some sweetened and flavored nontobacco products are sold for use in hookahs.15

- Labels and ads for these products often claim that users can enjoy the same taste without the harmful effects of tobacco.16

- Studies of tobacco-based shisha and “herbal” shisha show that smoke from both preparations contain carbon monoxide and other toxic agents known to increase the risks for smoking-related cancers, heart disease, and lung disease.16,17

- American Lung Association. Facts About Hookah Washington: American Lung Association, 2007 [accessed 2021 Apr 22].

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The Effects of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Epidemiology 2010;39:834–57 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- Cobb CO, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: An Emerging Health Crisis in the United States. American Journal of Health Behavior 2010;34(3):275–85 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- Johnston DL, Miech RA, O’Malley PM et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975-2018: Overview of Key Findings on Adolescents Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2019 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- Shulenberg JE, Johnston DL, O’Malley PM et al. Monitoring the Future National Survey on Drug Use 1975-2018: Volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19–60. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2019 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2016 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- El-Hakim Ibrahim E, Uthman Mirghani AE. Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Keratoacanthoma of the Lower Lips Associated with “Goza” and “Shisha” Smoking. International Journal of Dermatology 1999;38:108–10 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- Nuwayhid, I, Yamout, B., Ghassan, and Kambria, M. Narghile (Hubble-Bubble) Smoking, Low Birth Weight and Other Pregnancy Outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology 1998;148:375–83 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012 [accessed 2021 Jan 29].

- Shihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2003;41(1):143–52 [accessed 2021 Feb 10].

- World Health Organization. Tobacco Regulation Advisory Note. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Health Effects, Research Needs and Recommended Actions by Regulators. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative, 2005 [accessed 2021 Feb 10].

- American Lung Association. American Lung Association Tobacco Policy Trend Alert: An Emerging Deadly Trend: Waterpipe Tobacco Use, 2007 [accessed 2021 Feb 10].

- Cobb CO, Vansickel AR, Blank MD, Jentink K, Travers MJ, Eissenberg T. Indoor Air Quality in Virginia Waterpipe Cafés. Tobacco Control 2012 Mar 24 [accessed 2021 Feb 10].

- Shihadeh A, Salman R, Eissenberg T. Does Switching to a Tobacco-Free Waterpipe Product Reduce Toxicant Intake? A Crossover Study Comparing CO, NO, PAH, Volatile Aldehydes, Tar and Nicotine Yields. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012;50(5):1494–8 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].

- Blank MD, Cobb CO, Kilgalen B, Austin J, Weaver MF, Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. Acute Effects of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Control Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2011;116(1–3):102–9 [accessed 2021 Mar 18].