Epidemiology & Risk Factors

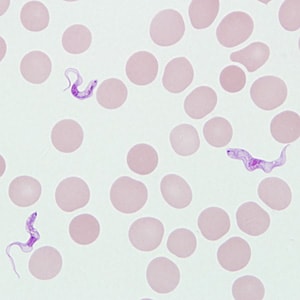

Trypomastigotes of T. brucei ssp. in a blood smear stained with Giemsa. Credit: DPDx

Two subspecies of the parasite Trypanosoma brucei, T. b. gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense, cause disease in humans, with clinical features of the infection dependent on the subspecies involved.

T. b. gambiense is endemic in western and central Africa, while T. b. rhodesiense is restricted to eastern and southern Africa. Their ranges do not overlap except in Uganda where both subspecies are co-endemic, with T. b. gambiense in the northwest corner of the country along the borders with South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and T. b. rhodesiense mostly clustered in the center of the country.

T. b. rhodesiense (East African sleeping sickness) is found in focal areas of eastern and southeastern Africa. In 2020, fewer than 100 cases of East African trypanosomiasis were reported to WHO (https://www.who.int/gho/neglected_diseases/human_african_trypanosomiasis/en/external icon). Domestic and wild animals are the main reservoir of infection. Cattle have been implicated in the spread of the disease to new areas and in local outbreaks. A wild animal reservoir is thought to be responsible for sporadic transmission to hunters and visitors to game parks. Infection of international travelers is rare, but it occasionally occurs and most cases of sleeping sickness imported into the U.S. have been in travelers who were on safari in East Africa.

T. b. gambiense (West African sleeping sickness) is found predominantly in central Africa and in limited areas of West Africa and accounts for most sleeping sickness in Africa. Although epidemics of sleeping sickness were a significant public health problem in the past, the disease is reasonably well-controlled at present, with less than 600 cases of West African trypanosomiasis reported to WHO in 2020; more than 50% of these were reported by the Democratic Republic of Congo. (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hat-tb-gambienseexternal icon). Humans are the most important reservoir of infection, although the parasite can sometimes be found in domestic animals (e.g., pigs, dogs, goats).

Close up of a tsetse fly taking a blood meal. Tsetse flies can transmit T. brucei.

Both forms of sleeping sickness are transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly (Glossina species). Tsetse flies inhabit rural areas, living in the woodlands and thickets that dot the East African savannah. In central and West Africa, they live in the forests and vegetation along streams. Tsetse flies bite during daylight hours. Both male and female flies can transmit the infection, but even in areas where the disease is endemic only a very small percentage of flies are infected. Although the majority of infections are transmitted by the tsetse fly, other modes of transmission are possible. Occasionally, a pregnant woman can pass the infection to her unborn baby (T. b. gambiense). In theory, the infection can also be transmitted by blood transfusion, sexual contact, organ transplantation and accidental laboratory exposure, but such cases are rare and poorly documented.

This information is not meant to be used for self-diagnosis or as a substitute for consultation with a health care provider. If you have any questions about the parasites described above or think that you may have a parasitic infection, consult a health care provider.