Information for Clinicians

Presentation

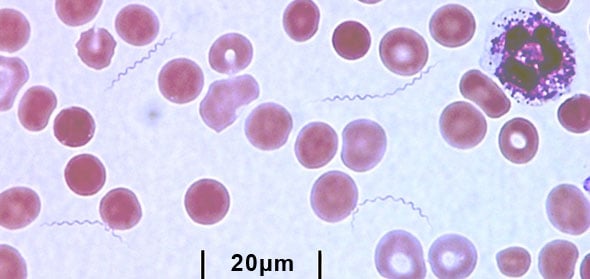

Relapsing fever is caused by certain species of Borrelia, a gram negative bacteria 0.2 to 0.5 microns in width and 5 to 20 microns in length. They are visible with light microscopy and have the cork-screw shape typical of all spirochetes. Relapsing fever spirochetes have a unique process of DNA rearrangement that allows them to periodically change the molecules on their outer surface. This process, called antigenic variation, allows the spirochete to evade the host immune system and cause relapsing episodes of fever and other symptoms. Three species cause TBRF in the United States: Borrelia hermsii, B. parkeri, and B. turicatae. The most common cause is cause is B. hermsii.

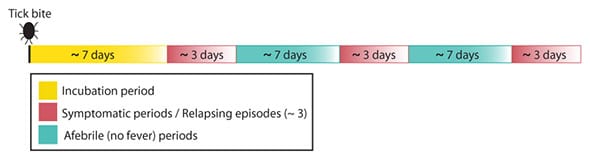

Tick-borne relapsing fever is characterized by recurring febrile episodes that last ~3 days and are separated by afebrile periods of ~7 days duration. Along with fever, patients may experience a wide range of nonspecific symptoms (Table 1). Each febrile episode ends with a sequence of symptoms collectively known as a “crisis.” During the “chill phase” of the crisis, patients develop very high fever (up to 106.7°F or 41.5°C) and may become delirious, agitated, tachycardic and tachypneic. Duration is 10 to 30 minutes. This phase is followed by the “flush phase”, characterized by drenching sweats and a rapid decrease in body temperature. During the flush phase, patients may become transiently hypotensive. Overall, patients who are not treated will experience several episodes of fever before illness resolves.

Physical Exam

Findings on physical exam vary depending on the severity of illness and when the patient seeks medical care. Regardless, there are no findings specific for TBRF. Patients typically appear moderately ill and may be dehydrated. Occasionally a macular rash or scattered petechiae may be present on the trunk and extremities. Less frequently, patients may have jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, meningismus, and photophobia (Table 1). Although less common, infection with B. turicatae is especially likely to result in neurologic involvement.

Table 1. Selected Symptoms and Signs among Patients with Tick-borne Relapsing Fever, United States*

| Symptom | Frequency of Symptom | Sign | Frequency of Sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 94% | Confusion | 38% |

| Myalgia | 92% | Rash | 18% |

| Chills | 88% | Jaundice | 10% |

| Nausea | 76% | Hepatomegaly | 10% |

| Arthralgia | 73% | Splenomegaly | 6% |

| Vomiting | 71% | Conjunctival Injection | 5% |

| Abdominal pain | 44% | Eschar | 2% |

| Dry cough | 27% | Meningitis | 2% |

| Eye pain | 26% | Nuchal rigidity | 2% |

| Diarrhea | 25% | ||

| Photophobia | 25% | ||

| Neck pain | 24% |

*Abstracted from Dworkin, M. S., et al. Tick-borne relapsing fever in the northwestern United States and southwestern Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1998; 26: 122-31.

Laboratory Testing

Spirochetemia (spirochetes in blood) in TBRF patients often reaches high concentrations (>106 spirochetes/ml). Thus, microscopy is a useful diagnostic tool for TBRF. The diagnosis of TBRF may be based on direct microscopic observation of relapsing fever spirochetes using dark field microscopy or stained peripheral blood smears. Spirochetes are more readily detected by microscopy in symptomatic, untreated patients early in the course of infection. Other bacteria, such as Helicobacter, may appear morphologically similar, so it is important to consider clinical and geographical characteristics of the case when making a diagnosis of TBRF based on microscopy. Additional testing, such as serology or culture, is recommended.

Wright-Giemsa stained peripheral blood smear. The TBRF bacteria are long and spiral-shaped. The circular objects are red blood cells. The irregular purple object in the top right corner is a white blood cell.

Serologic testing for TBRF is not standardized and results may vary by laboratory. Serum taken early in infection may be negative, so it is important to also obtain a serum sample during the convalescent period (at least 21 days after symptom onset). A change in serology results from negative to positive, or the development of an IgG response in the convalescent sample, is supportive of a TBRF diagnosis. However, early antibiotic treatment may limit the antibody response. Patients with TBRF may have false-positive tests for Lyme disease because of the similarity of proteins between the causative organisms. A diagnosis of TBRF should be considered for patients with positive Lyme disease serology who have not been in areas endemic for Lyme disease.

Speciation of the relapsing fever Borrelia is typically not done in absence of a culture. The Borrelia species is often inferred from the location of the patient’s exposure. If the exposure occurred in a western state, at high elevation (1200-8000 feet), TBRF is usually due to Borrelia hermsii. If the exposure occurred in a southern state, specifically Texas or Florida, at lower elevation, TBRF is usually due to Borrelia turicatae.

Incidental laboratory findings include normal to increased white blood cell count with a left shift towards immature cells, a mildly increased serum bilirubin level, mild to moderate thrombocytopenia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and slightly prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT).

Treatment of Tick-borne Relapsing Fever

TBRF spirochetes are susceptible to penicillin and other beta-lactam antimicrobials, as well as tetracyclines, macrolides, and possibly fluoroquinolones. CDC has not developed specific treatment guidelines for TBRF; however, experts generally recommend doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days as the preferred oral regimen. Azithromycin 500 mg daily for 10 days is an effective alternative when doxycycline is contraindicated. Parenteral therapy with ceftriaxone 2 grams per day for 10-14 days is preferred for patients with central nervous system involvement or for patients who are pregnant. In contrast to TBRF, LBRF caused by B. recurrentis can be treated effectively with a single dose of antibiotics.

When initiating antibiotic therapy, all patients should be observed during the first 4 hours of treatment for a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The reaction, a worsening of symptoms with rigors, hypotension, and high fever, occurs in over 50% of cases and may be difficult to distinguish from a febrile crisis. Cooling blankets and appropriate use of antipyretic agents may be indicated. In addition acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation has been described recently in several patients undergoing treatment for TBRF.

Complications and Prognosis

Given appropriate treatment, most patients recover within a few days. Long-term sequelae of TBRF are rare but include iritis, uveitis, cranial nerve and other neuropathies.

Tick-borne Relapsing Fever in Pregnancy

TBRF contracted during pregnancy can cause spontaneous abortion, premature birth, and neonatal death. The maternal-fetal transmission of Borrelia is believed to occur either transplacentally or while traversing the birth canal. In one study, perinatal infection with TBRF was associated with lower birth weights, younger gestational age, and higher perinatal mortality (Jongen, van Roosmalen et al. 1997).

In general, pregnant women have higher spirochete loads and more severe symptoms than nonpregnant women. Higher spirochete loads have not, however, been found to correlate with fetal outcome.

Immunity

Although there is limited information on the immunity of TBRF, there have been patients who developed the disease more than once.

Public Health Reporting Requirements

Although not a nationally notifiable condition, prompt reporting of TBRF cases is currently required in at least 12 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington. Regardless of location, health care providers should report cases to appropriate state or local health authorities. Large multistate outbreaks have been linked to rental cabins near national parks and other common vacation locations, and prompt reporting by clinicians was critical to the identification and control of these outbreaks. Without corrective action, tick-infested cabins can remain a source of human infection for many years.