Fire Fighter Dies as a Result of a Cardiac Arrest During an Apartment Fire - Louisiana

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F98-15 Date Released: August 10, 1998

SUMMARY

On November 18, 1997, a 27-year-old male fire fighter collapsed while fighting a fire in a two-bedroom apartment located on the second floor of a multi-unit apartment building. The fire involved the bed and night table in the apartment’s master bedroom and had generated a moderate amount of smoke. The fire fighter, who was wearing full turnout gear and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), was assisting an attack crew on the second floor landing in front of the apartment. According to witnesses, the fire fighter showed no signs of distress when he began to descend the stairway. Approximately, half-way down the 15-step stairway, he collapsed.

Nearby fire fighters immediately initiated cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), followed by advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) from the responding ambulance service. Seventeen minutes after his collapse, he arrived at the hospital emergency department. Care provided at the emergency department eventually stabilized his cardiovascular status, but anoxic (without oxygen) brain damage had already occurred. On November 23, 1997, life support machines were disconnected and, shortly thereafter, he died. The autopsy report listed anoxia as the immediate cause of death.

The following recommendations address health and safety issues in general, as well as problems uncovered during the NIOSH investigation. It is unlikely, however, that any of these recommendations could have prevented the sudden cardiac arrest and subsequent death of this fire fighter. These recommendations rely on a three-pronged strategy for reducing the risk of on-duty heart attacks and cardiac arrests among fire fighters proposed by other agencies. This strategy consists of: 1) minimizing physical stress on fire fighters; 2) screening to identify and subsequently rehabilitate high risk individuals; and 3) encouraging increased individual physical capacity. Steps that could be taken to accomplish these ends include:

- Provide adequate fire fighter staffing to ensure safe operating conditions.

- Implement a personnel accountability system such as one recommended by NFPA 1561, Standard on Fire Department Incident Management System, Section 2-6.

- Implement an incident management system with written procedures for all fire fighters.

- Provide fire fighters with annual medical evaluations for clearance to wear SCBA. These clearance evaluations are required for private industry employees and public employees in States operating OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) approved State plans

- All personnel entering a potentially hazardous atmosphere must wear a SCBA.

- The content and frequency of the fire fighter medical evaluations should be consistent with those required by OSHA and recommended by NFPA, and the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs.

- Reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity by implementing a wellness/fitness program for fire fighters.

- When the function of a SCBA is questioned in a fire fighter’s injury or death, NIOSH is available to perform objective, expert testing of the SCBA.

INTRODUCTION & METHODS

On November 18, 1997, a 27-year-old male fire fighter collapsed while fighting a fire. Despite immediate CPR administered by fire fighters and ACLS by the ambulance service and the emergency room, the fire fighter suffered severe anoxic brain damage. On November 23, 1997, life support machines were disconnected and, shortly thereafter, he died. NIOSH was notified of this fatality on April 3, 1998 by the deceased fire fighter’s mother. On April 6, 1997, NIOSH telephoned the affected Fire Department and City Personnel Director to initiate the investigation. On April 28, 1998, Tommy Baldwin, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, and Thomas Hales, Senior Medical Officer from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Team traveled to Louisiana to conduct an onsite investigation of the incident.

During the investigation NIOSH personnel met with and interviewed the:

- City Personnel Director;

- Fire Department Inspector;

- Local President of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF);

- Fire Department personnel involved in this incident;

- Ambulance personnel responding to this incident;

- Family members;

- Maintenance Chief responsible for investigation of the victim’s SCBA;

- Forensic Investigator from the Coroner’s Office.

During the site-visit NIOSH personnel also reviewed:

- Existing Fire Department investigative records, including incident reports, co-worker statements, dispatch records, the victim’s annual medical evaluation, SCBA inspection report, and photographs of the fire scene;

- Fire Department policies and operating procedures;

- Fire Department training records;

- Fire Department annual report for 1997;

- Past medical records of the deceased;

- Autopsy results and death certificate of the deceased;

- Ambulance dispatch records and response form;

- Hospital records related to this incident.

NIOSH personnel also:

- Visited the fire scene;

- Contacted physicians caring for the fire fighter during his hospitalization;

- Contacted the physician performing the autopsy.

INVESTIGATIVE RESULTS

Fire Scene Response. On November 18, 1997, at 0738 hours, the police department was notified by the building manager of an apartment fire. The police dispatcher notified the fire department, which ordered Engine 3, Engine 5, and Unit 200 (Acting District Chief) to respond. The victim had been relieved of duty just prior to the fire call, but was still present at the fire station when the call was received. Upon hearing the call, he responded in his personal vehicle and was the first fire fighter to arrive at the fire scene at approximately 0740 hours.

At that time, a small amount of fire was showing from the window of a second floor apartment, while a moderate amount of smoke was showing on the second floor landing. The victim donned his bunker gear, which he carried in his vehicle, and ascended the stairs to the second floor landing outside the burning apartment. Witnesses could not see the victim on the second floor landing; therefore, it is unclear whether the victim entered either the involved apartment or any of the adjacent apartments. Both Engines and Unit 200 arrived at the fire scene between 0740 and 0741 hours. The victim proceeded to descend the stairs and retrieve a SCBA from Engine 3.

The Acting District Chief arrived at 0741 hours and assumed command from the ranking Captain on Engine 3. A second Captain from Engine 3 donned his SCBA and ascended the front stairs to the second floor to search the apartments for fire spread. He noticed the door to the involved apartment was partially open. (After the occupants had exited the apartment, they told the maintenance man their apartment was on fire. The maintenance man notified other building residents to exit the building and closed the door to the involved apartment). The second Captain looked into the involved apartment and saw moderate smoke banking down to floor level. He also looked into the apartment next door but saw no fire spread.

Meanwhile, a Captain from Engine 5 donned his SCBA and advanced the 1½-inch crosslay hoseline up the rear stairs to the second floor landing. There, he was joined by the second Captain from Engine 3, and they both entered the involved apartment to begin fire extinguishment. They encountered dense smoke in the interior hallway banked down to the floor level. As they approached the seat of the fire in the back bedroom, the heat intensified. While the attack was in progress, the Acting District Chief and the apartment complex maintenance man disconnected the electric meter to the apartment.

The victim, after donning a SCBA, ascended the front stairs to the second floor landing. Moments later, he walked to the rear stairs and descended approximately six to seven steps, then he collapsed.

His collapse was witnessed by one of the Captains who caught the victim as he fell. According to the witness, the victim showed no signs of respiratory, or any other type of, distress before his collapse.

EMS Response to the Medical Emergency. The Captain who caught the victim noted that the victim was unresponsive and immediately requested an ambulance. He proceeded to carry the victim, with assistance, from the stairs to the ground, and then carried him another 100 feet from the building. During the carry, the victim’s SCBA face mask and bunker gear were removed, revealing cyanotic skin coloring and clear frothy fluid coming from his mouth. After laying him on the ground, fire fighters checked his vital signs which, were absent, and initiated CPR. The fire fighters performing CPR met resistance in delivering air to the victim’s lungs (ventilations), and the victim’s head was repositioned and a pocket face mask was used to deliver the air. Despite these maneuvers, ventilation remained difficult. Fire fighters performing CPR reported that the victim briefly regained a pulse, but slipped back into cardiac arrest prior to the arrival of the ambulance.

Two ambulances were dispatched at 0746 hours, responded at 0747 hours, and arrived on scene at 0749 hours. Each ambulance was staffed by a paramedic and an emergency medical technician. Upon arrival, ambulance personnel performed a cardiac monitor check of the victim and found him to be in ventricular fibrillation (V.Fib). Using a defibrillator, the paramedic administered a shock (200 joules) and checked the victim’s cardiac rhythm. Still in V.Fib, the victim was shocked again (300 joules). The victim was then intubated and an IV line was established. Lung sounds were checked for proper tube placement. The victim was then placed onto an ambulance cot and loaded into the ambulance. The ambulance left the scene bound for the hospital at 0758 hours. Resuscitation measures continued en-route, and the victim briefly regained a pulse for approximately 25 seconds before deteriorating into cardiac arrest. Throughout the pre-hospital resuscitation efforts, the victim remained unconscious and cyanotic. Arrival time at the hospital was 0803 hours.

Upon arrival in the hospital’s emergency department, the victim was transferred from the ambulance cot onto a hospital bed. Resuscitation measures continued while blood samples were taken and checks were made for placement of his IV line and endotrachial tube. Although the IV line was properly positioned, the endotrachial tube was found to be in the patient’s esophagus and was thought to have slipped out of the trachea during the transfer from the ambulance cot to the hospital bed. The tube was repositioned and resuscitation efforts continued. On initial examination in the emergency department, the victim was found to have a slow heart rate (30 beats/minute) with no pulse, no spontaneous respiration, no blood pressure, and no signs of life. After approximately 5-10 minutes of ACLS in the hospital’s emergency department, the victim’s cardiovascular system stabilized. However, he never regained consciousness or spontaneous respirations and required the use of a life support machine (ventilator). Subsequent neurological examinations complimented by a CT (computerized tomography) scan and serial EEGs (electroencephalograms), revealed severe anoxic (lack of oxygen) brain damage. On November 23, 1997, due to his exceedingly grave prognosis, the life support machine was disconnected and he died shortly thereafter.

Medical Findings. The death certificate was completed by the coroner. The immediate cause of death was listed as “cerebral anoxia with edema and congestion.” Blood tests in the emergency department revealed a carboxyhemoglobin level of 1.4%, indicating that the deceased was not exposed to excessive concentrations of carbon monoxide prior to his death. A blood drug screen was negative, indicating that his cardiac arrest was not due to cocaine. In addition, a blood cyanide level was normal, indicating that his cardiac arrest was not due to the inhalation of cyanide (which can be generated by the burning of certain synthetic materials).

Medical records indicated that he had history of cardiac arrhythmias (A-V node re-entrant tachycardia) diagnosed in 1994 by an electrophysiologic study for which he received therapy (radiofrequency ablation). Since the ablation procedure, the patient did not experience any subsequent episodes of fast heart beats (palpitations). He had one risk factor for coronary artery disease, but had no evidence of coronary artery disease on autopsy. Pertinent findings from the autopsy performed by the medical examiner on 11/24/98 are listed below:

- No evidence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

- No evidence of significant valvular problems.

- A small scar (1 cm) in the heart muscle, consistent with his previous ablation procedure.

- No soot in the throat (trachea-bronchial tree), consistent with no smoke inhalation

- Changes in the brain, heart, kidney, and lungs consistent with the prolonged lack of oxygen (anoxia), and subsequent maintenance on life support machines.

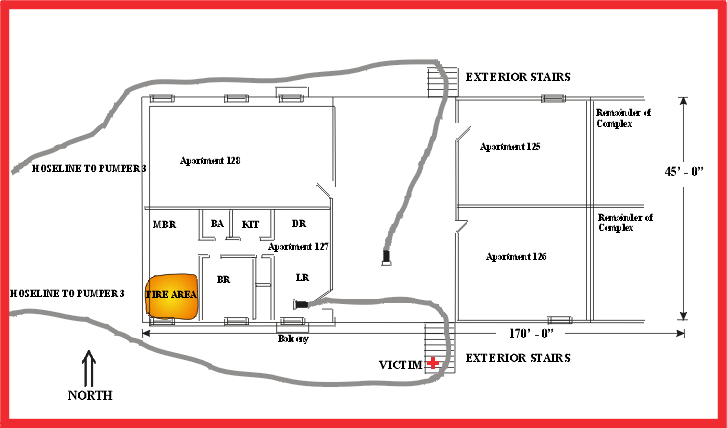

Description of the Fire Scene and Response. The site of the incident was a two-story multi-unit apartment building constructed of protected wood frame with brick veneer on the first floor, and wooden siding on the second floor. The gable roof was covered with asphalt shingles. Each two-story building contained two adjoining sections. Each floor contained two apartments on each side of the breezeway, for a total of four apartments per floor per section (see attached figure). An exterior stairway connected the second-level landing on each end of the breezeway with the ground level. The apartments did not contain a fire sprinkler system nor a fire alarm system. The involved apartment was equipped with a smoke detector, which was not operational at the time of the fire.

The origin of the fire was reported to be a cigarette on the bedding material. Materials burned included the bedding material, foam mattress, and night table. It took the fire fighters approximately five minutes to extinguish the fire before overhaul operations were initiated. Overall, 26 fire fighters were on scene, including eight on-duty, 17 off-duty, and one volunteer. Total time at the fire scene was approximately four hours.

DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT

At the time of the NIOSH investigation, the fire department was comprised of 48 fire fighters and served a population of 35,000 in a geographic area of 12 square miles. At the time of the NIOSH site-visit, there were fourteen vacancies, including the Fire Chief and Training Officer positions, which had been vacant for approximately eleven months. There are five fire stations and one central station. Fire fighters work 24 hours on duty (0800 hours to 0800 hours) and are off 48 hours. Each Engine company is staffed with 2-3 fire fighters. In 1997, the department responded to 527 calls: 155 fires/explosions; 11 overpressure/rupture; 42 emergency medical/rescue; 79 hazardous conditions; 44 service; 105 good intent; 55 false alarms; 36 mutual aid.

Training. The fire department provides all new fire fighters with the basic 240-hour recruit training required by the State of Louisiana. The department also requires 20 hours of additional on-the-job training each month. The training is provided primarily during in-services by the company officers of each engine company. The victim had 1.5 year’s of fire fighting experience, and 715 hours of fire fighter training and was a Fire Fighter First Class.

Personal equipment, such as SCBA, turnout gear, etc., is checked by each fire fighter at the beginning of their shift. Any equipment not found in working order is sent for maintenance or repaired on site. The Maintenance Chief was responsible for securing and testing the victim’s SCBA for defects. Compressor and cylinder samples were tested separately by local and national vendors. The respirator was checked by a regional vendor. All tests revealed normal gas content and operation.

Medical Clearance and Physical Fitness. All fire fighters in this department receive a pre-employment and annual medical evaluation. The evaluation consists of a medical history, vision testing, physical examination, and blood and urine tests. Other tests can be ordered at the discretion of the examining physician. The department does not have a separate medical clearance evaluation to wear a respirator. The victim had passed his annual medical evaluation approximately five months prior to his cardiac arrest.

All fire fighters in this department must pass a physical agility test at two separate times. The first required test occurs when the fire fighter converts from a temporary employee to a permanent employee (six months after being hired). The second required test is upon promotion to fire fighter first class. The physical agility test is a timed test of donning bunker gear and SCBA, unrolling and rolling a hose, laddering a building, chopping wood with an ax, entering and searching for a practice dummy in a smoke filled building, removing the dummy (approximately 150 pounds) from the building, and carrying the dummy around the outside of the building. Although physical fitness was encouraged at training sessions, there were no programs in place to enhance cardiovascular/respiratory fitness of fire fighters.

DISCUSSION

Prior to our investigation, the fire department and medical community considered this event to be a primary respiratory (lung) failure, presumably due to the inhalation of toxic smoke. We consider this to be unlikely for several reasons.

- There was no conclusive proof that the victim entered the affected apartment where the smoke was concentrated.

- If the victim entered the apartment, it could have only been for a brief period of time, given the time sequence listed above and the fact that his carboxyhemoglobin was not elevated (carboxyhemoglobin is a measure of carbon monoxide exposure – a major constituent of fire smoke).

- It would be unusual for primary respiratory failure to act in such a sudden manner, particularly without the victim showing signs of respiratory distress prior to his collapse.

- It would be unusual for primary respiratory failure to cause ventricular fibrillation in such a rapid manner.

- Chest x-rays during his hospitalization showed no signs of toxic lung damage (pneumonitis).

- In general, once his cardiovascular system stabilized, his lungs were able to adequately oxygenate his blood.

- The autopsy did not reveal any soot in his lungs (tracheobronchial tree) suggesting insignificant or no smoke inhalation.

Approximately three minutes after the victim’s collapse, paramedics found the victim in V.Fib. V.Fib is the most common type of arrhythmia associated with cardiac arrest, occurring in 65-80% of all cardiac arrests.1 In the United States, coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis) is the most common risk factor for sudden cardiac death and cardiac arrest (80%), followed by heart muscle problems (cardiomyopathies) (15%), and then a multitude of other factors (5%), including abnormal heart rhythms (structural electrophysiologic abnormalities).1 On autopsy the victim did not have coronary artery disease or heart muscle problems. However, his medical records indicated that he did have an abnormal heart rhythm (A-V node reentrant tachycardia) that was successfully treated by radiofrequency ablation in 1994. While other types of reentrant tachycardia (Wolff-Parkinson-White) have been associated with V.Fib.,2-5 his rhythm (A-V node reentrant tachycardia) has not been reported to degenerate into V.Fib. Other cases of V.Fib have been reported from electrical shock, pesticide (organophosphate) poisoning, yew leaf ingestion, or blunt trauma to the chest.6-8 There is no evidence that any of these occurred in this situation. Finally, it is possible, but exceedingly unlikely given the medical data and accounts of his activities at the scene, that toxic fumes (e.g. cyanide) from the foam mattress could have produced toxicity to the heart’s electrical system.

In a small minority of cases of V.Fib, the cause is unknown (idiopathic).9-12 Hypothesized reasons for these otherwise unexplained cases include the release of exercise-induced stress hormones (catecholamines),4, 9 coronary artery disease spasm, 13, 14 or genetics.11

Firefighting activities are strenuous and often require fire fighters to work at near maximal heart rates for long periods. The increase in heart rate has been shown to begin with responding to the initial alarm and persist through the course of fire suppression activities.15 Climbing stairs, such as the access stairs from street level to the involved apartment, in full turnout gear involves a high energy cost. For example, studies of fire fighters climbing stairs in full equipment found that the fire fighters reached 80% of their maximum oxygen consumption and 95% of their maximal heart rate.16, 17 It is possible that the physical exertion and mental strain encountered while responding to this fire caused this individual’s V.Fib. We cannot, however, explain why it happened at this particular time at this particular fire.

Our investigation has not definitively identified the cause of this fire fighter’s cardiac arrest, but we do not believe it was due to smoke inhalation. The physical stress of fire fighting activities in combination with his A-V node reentrant tachycardia condition may have contributed to his cardiac arrest. In either case, given this fire fighter’s young age, good aerobic conditioning based on his pre-employment physical agility test, lack of underlying coronary artery disease, immediate initiation of CPR, and rapid initiation of defibrillation, it is puzzling why he was so recalcitrant to resuscitation efforts.10

RECOMMENDATIONS AND DISCUSSION:

The following recommendations address health and safety generally, as well as problems uncovered during the NIOSH investigation. It is unlikely, however, that any provisions of these recommendations could have prevented the sudden cardiac arrest and subsequent death of this fire fighter. This list includes some preventive measures that have been recommended by other agencies to reduce the risk of on-the-job heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters. These recommendations have not been evaluated by NIOSH, but represent research presented in the literature or of consensus votes of Technical Committees of the National Fire Protection Association or labor/management groups within the fire service. In addition, they are presented in a logical programmatic order, and are not listed in a priority manner.

Recommendation #1: Provide adequate fire fighter staffing to ensure safe operating conditions.

Over the year preceding the incident, there had been approximately 14 vacancies within this fire department. While hiring fire fighters for these positions has been complicated by many factors, including the absence of a Chief for eleven months, these positions are needed to fight fires in a safe manner.

Recommendation #2: Implement a personnel accountability system such as one recommended by NFPA 1561, Standard on Fire Department Incident Management System, Section 2-6.

This system provides for the rapid tracking and inventory of all members operating at the incident scene.18 A large percentage of fire fighter deaths at the fire scene are due to the absence or failure of such an accountability system. 18 At this fire, the incident commander was initially unaware of this fire fighter’s presence at the fire scene. Although this was not responsible for this fire fighter’s death, it did point out the lack of such a system for this department.

Recommendation #3: Implement an incident management system with written procedures for all fire fighters.

Like accountability, poor incident management procedures may contribute to many of the fire fighter fatalities at the fire scene. A good incident command system provides a well-coordinated approach to any emergency. It not only identifies all personnel at the scene and their respective assignments, but provides up-to-the minute status, location and amount of all operational equipment. All fire fighters should be trained in every aspect of the incident command system to ensure that they understand the system and know their role during emergency operations. Although this department has an incident command procedure, it needs to be updated. We recommend a comprehensive incident management program, such as NFPA 1561, Standard on Fire Department Incident Management System.18

Recommendation #4: Provide fire fighters with annual medical evaluations for clearance to wear SCBA. These clearance evaluations are required for private industry employees and public employees in States operating OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) approved State plans.

OSHA’s revised respiratory protection standard requires employers to provide medical evaluations and clearance for employees using respiratory protection.19 Because municipal fire departments are public agencies with public employees, and because Louisiana does not operate an OSHA-approved State plan, they are not required to follow these OSHA standards. Nonetheless, we recommend voluntary compliance with this aspect of the respiratory protection standard to ensure that fire fighters can safely wear SCBA. Given the content and frequency of your current medical evaluations, compliance with this aspect of the OSHA standard would be a simple administrative procedure and not require any additional medical resources.

Recommendation #5: All personnel entering a potentially hazardous atmosphere must wear a SCBA.

SCBA must be worn when a fire fighter enters an area that is considered immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) or potentially IDLH or where the atmosphere is unknown. Smoke, vapor, or fumes from a fire or hazardous material incident may contain many toxic components. Some of these components will have immediate effects on the unprotected fire fighter (e.g. carbon monoxide poisoning) while others are cumulative, caused by years of exposure (e.g. smoke particulates). While this department maintains this policy in writing, several fire fighters reported it is not always followed in practice. At this particular incident, it is unclear if the victim (without a SCBA) actually entered the affected apartment, but he did at least reach the second floor landing where a moderate amount of smoke had accumulated.

Recommendation #6: The content and frequency of the fire fighter medical evaluations should be consistent with those required by OSHA and recommended by NFPA, and the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs.

The department’s current medical evaluation program is probably being conducted too frequently for younger employees. These evaluations are not harmful, but represent an unnecessary expense for the department. Guidance regarding the content and scheduling of periodic medical examinations for fire fighters can be found in NFPA 1582, Standard on Medical Requirements for Fire Fighters,20 and in the report of the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs wellness/fitness initiative.21 As discussed previously, the department is not legally required to follow OSHA standards.

In addition to providing guidance on the frequency and content of the medical evaluation, NFPA 1582 provides guidance on medical requirements for persons performing fire fighting tasks. Applying NFPA 1582 involves legal and economic repercussions, so it should be carried out in a nondiscriminatory manner. Appendix D of NFPA 1582 provides guidance for Fire Department Administrators regarding legal considerations in applying the standard. Economic repercussions go beyond the costs of administering the medical program. Department administrators, unions, and fire fighters must also deal with the personal and economic costs of the medical testing results. NFPA 1500 addresses these issues in Chapter 8-7.1 and 8-7.2.22 The success of medical programs may hinge on protecting the affected fire fighter. The department should provide alternate duty positions, if possible, for fire fighters in rehabilitation programs. If the fire fighter is not medically qualified to return to duty after repeat testing, supportive and/or compensated alternatives for the fire fighter should be pursued by the Department.

Recommendation #7: Reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity by implementing a wellness/fitness program for fire fighters.

NFPA 1500 requires a wellness program that provides health promotion activities for preventing health problems and enhancing overall well-being.22 In 1997, the International Association of Fire Fighters and the International Association of Fire Chiefs joined in a comprehensive Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative to improve fire fighter quality of life and maintain physical and mental capabilities of fire fighters. Ten fire departments across the United States joined this effort to pool information about their physical fitness programs and to create a practical fire service program. They produced a manual with a video detailing elements of such a program.21 Fire departments should review these materials to identify applicable elements for their department.

Recommendation #8: When the function of a SCBA is questioned in a fire fighter’s injury or death, NIOSH is available to perform objective, expert testing of the SCBA.

Given the initial thought that this was a primary respiratory collapse, the department did a very good job of securing the SCBA gear for testing. If this situation should arise again, personnel at the Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, Air Supplied Respirator Section, (304) 285-5907, are available to perform an objective evaluation of the SCBA free of charge.

REFERENCES

1. Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al. [1998]. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 14th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 222-225.

2. Klein GJ, Gallagher JJ, Smith WM, et.al. [1979]. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med 301:1080-5.

3. Peters RW, Scheinman MM, Gonzalez R [1981]. Atrial and ventricular vulnerability in a patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 4:17-22.

4. Cosio FG, Benditt DG, Kriett JM, et.al. [1982]. Onset of atrial fibrillation during antidromic tachycardia: association with sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation in a patient with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol 50:353-9.

5. Teo WS, Kim YH, Leather RA, et.al. [1991]. Multiple accessory pathways in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome as a risk factor for ventricular fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 67:889-91.

6. Cox A [1992]. Ventricular dysrhythmia secondary to select environmental hazards. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs 3:233-42.

7. von der Werth J, Murphy JJ [1994]. Cardiovascular toxicity associated with yew leaf ingestion. Br Heart J 72:92-3

8. van Amerongen R, Horwitz J, Winnik G, et al. [1997]. Ventricular fibrillation following blunt chest trauma from a baseball. Pediatr Emerg Care 13:107-10.

9. Buja G, Bellotto F, Meneghello MP [1989]. Isolated episode of exercise-related ventricular fibrillation in a healthy athlete. Int J Cardiol 24:121-3.

10. Dickey W, Adgey AA [1991]. Out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation in patients under the age of 40 years and the long-term prognosis. Q J Med 81:821-7.

11. Jordaens L, Dimmer C, Kazmierczak J, et al. [1997]. Ventricular arrhythmias in apparently healthy subjects. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 20:2692-8.

12. Kasanuki H, Hosoda S, Toyoshima Y, et al. [1997]. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation induced with vagal activity in patients without obvious heart disease. Circulation 95:2277-85

13. Behrens S, Schroder R, Bruggemann T, et.al. [1994]. Ventricular fibrillation related to coronary spasm in patients without significant coronary or other structural heart disease. Clin Investig 72:307-12.

14. Attenhofer C, Amann FW, Burkhard R, et al. [1994]. Ventricular fibrillation in a patient with exercise-induced anaphylaxis, normal coronary arteries, and a positive ergonovine test. Chest 105:620-2.

15. Barnard RJ, Duncan HW [1975]. Heart rate and ECG responses of fire fighters. J Occup Med 17:247-250.

16. Manning JE, Griggs TR [1983]. Heart rate in fire fighters using light and heavy breathing equipment: Simulated near maximal exertion in response to multiple work load conditions. J Occup Med 25:215-218.

17. Lemon PW, Hermiston RT [1997]. The human energy cost of fire fighting. J Occup Med 19:558-562.

18. National Fire Protection Association [1996]. NFPA 1561, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program. Quincy MA: NFPA.

19. 29 CFR 1910.134. Code of Federal Regulations. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Respiratory Protection. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, Office of the Federal Register.

20. National Fire Protection Association [1997]. NFPA 1582, Standard on Medical Requirements for Fire Fighters. NFPA, Quincy MA: NFPA.

21. International Association of Fire Fighters [1997]. The fire service joint labor management wellness/fitness initiative. Washington, DC: IAFF, Department of Occupational Health and Safety.

22. National Fire Protection Association. [1997]. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program. Quincy MA: NFPA.

Figure. Diagram of Fire Scene.

This page was last updated on 11/21/05