One Fire Fighter Dies and Another is Severely Injured in a Single Vehicle Rollover Crash - Georgia

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2009-08 Date Released: August 27, 2009

SUMMARY

On February 23, 2009, a 34-year-old male volunteer/paid on-call fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured and another fire fighter was severely injured in a single vehicle rollover crash. The crash occurred when the fire truck was unable to stop while crossing an intersection, swerved to avoid traffic and overturned into a utility pole. The fire truck was responding code 3 (lights and siren) to a reported brush fire on a two-lane paved road with a posted speed limit of 55 mph. The driver and the passenger (the victim) were not wearing seat belts and were found lying next to the cab on the passenger side. The victim died from his injuries at the scene and the driver was transported to the hospital with serious injuries. Key contributing factors identified in this investigation include: non-use of seatbelts, an inadequate vehicle inspection and maintenance program, inadequate driver training and inexperience with this specific apparatus, an older apparatus with minimal safety features, and “lights and siren” response with an auxiliary apparatus not designed for higher-speed on-road emergency response.

|

|

Crash Scene Photo. |

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that standard operating procedures (SOPs) regarding seatbelt use are established and enforced

- ensure that programs are in place to provide for the inspection, maintenance, testing, and retirement of automotive fire apparatus

- provide and ensure all drivers successfully complete a comprehensive driver’s training program such as NFPA 1451, Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program, before allowing a member to drive and operate a fire department vehicle

- consider replacing fire apparatus more than 25 years old

- consider downgrading the emergency response code for auxiliary fire apparatus such as brush fire support vehicles

- be aware of programs that provide assistance in obtaining alternative funding, such as grant funding, to replace or purchase fire apparatus and equipment

Additionally, federal and state departments of transportation should

- consider modifying or removing exemptions that allow fire fighters to not wear seat belts

INTRODUCTION

On February 23, 2009, a 34-year-old male volunteer/paid on-call fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured and another fire fighter was severely injured in a single vehicle rollover crash. On February 24, 2009, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this fatality. On March 9, 2009, an occupational safety and health specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program traveled to Georgia to investigate the incident. Photographs of the incident scene as well as the involved fire apparatus were taken. The NIOSH investigator met with representatives from the county administration, fire fighters and officers from the involved fire department, the county coroner, and a member of the Georgia Local Assistance State Team (LAST) from the National Fallen Fire Fighters Foundation. Interviews were conducted with the fire department district chief of the county fire departments, the chief and fire fighters from the involved fire department, and the driver of the apparatus involved in the incident. The NIOSH investigator reviewed the department’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), the victim’s and driver’s training records, fire department photographs of the incident scene, the coroner’s report, and the certificate of death. The NIOSH investigator was accompanied by a fire department representative to inspect the involved fire apparatus at a secured impound yard and to examine the incident scene. Information regarding the pumper’s original drive train was obtained by NIOSH through the vehicle identification number (VIN) and parts identification list with the assistance of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and by reviewing records located in the vehicle.

FIRE DEPARTMENT

The volunteer/paid on-call fire department involved in this incident has 6 fire stations. Each station has their own chief and membership and is organized under a county district fire chief who provides administrative and operational support. The department covers a geographical area of 178 square miles and responds to approximately 239 emergency incidents per year. A total of 47 volunteer members serve a population of about 10,000 residents.

The department has the following apparatus in service:

- 2006, 1,250 gpm commercial pumper

- 1998, 1,250 gpm commercial pumper

- 1987, 1,250 gpm commercial pumper

- 1986, 1,000 gpm commercial pumper

- 1981, 1,250 gpm custom pumper

- 1998, 2,500 gallon tanker

- 2 rescue trucks, (2006 and a 2001 commercial chassis)

- 4 fire knockers,a (Engine-4, a 1964 commercial chassis truck with a 320 gpm pump and a 1,000 gallon tank, [unit involved in this incident]; a 1973 commercial chassis with a 320 gpm pump and a 1,000 gallon tank; a 1975 commercial chassis with a 320 gpm pump and a 1,000 gallon tank; and, a 1993 commercial chassis with a 1,750 gallon tank).

The department did not have a written seatbelt policy or a written vehicle maintenance program. The department did not have a vehicle inspection policy or operational checklist for department vehicles, but did have a detailed SOP for emergency vehicle response involving both privately owned vehicles (POV) and fire apparatus. For fire apparatus responding to an emergency call, procedures include the qualifications of operators, a list of items to be checked before leaving the station, response speeds appropriate to road and weather conditions, right-of-way reminders, engaging the parking brake after arrival on scene, responding through intersections and traffic lights, and regard for the safety of responders and others.

The department did not have any other written SOPs or guidelines regarding apparatus maintenance or operation of vehicles and equipment. Procedures for vehicle maintenance were limited to verbally notifying the county district chief of any problems with apparatus or needed maintenance. Apparatus maintenance was previously performed by the county maintenance department and was contracted out after the county facility was closed in 2007. Limited maintenance records for apparatus repair and general maintenance were kept at the county facility.

a Fire knocker is a term used to describe fire fighting equipment that is part of a cooperative equipment lease between the Georgia forestry commission and the locality. The apparatus involved in this incident was included in the lease agreement.

Apparatus

The apparatus involved in this incident was a 1964 model, 320 gallon per minute (gpm) fire truck equipped with a 1,000-gallon water tank mounted on a 163-inch wheelbase commercial chassis with a maximum gross vehicle weight rating of 20,000 lbs. The 1,000-gallon (baffled) water tank was reported to be full at the time of the incident. The water in the full water tank would have weighed approximately 8,360 lbs. State police reported the empty truck weighed 10,900 lbs after the incident. The truck was equipped with a 330-cubic inch gasoline engine. The transmission was a 4-speed (split range) manual reported to be synchronized.b The NIOSH investigator was able to determine through the vehicle identification number that the original transmission was a synchronized, 4-speed manual transmission. The tires were bias ply and tread patterns on the right front tire indicated an uneven wear pattern consistent with alignment or steering assembly mechanical issues (see Photo 1). Tread depth on the left front tire and rear tires were not considered factors (4/32 inch left front, 12/32 inch rear x 4). The apparatus had a conventional cab with lap-type seat belts that appeared to function correctly. The apparatus odometer indicated 35,405 miles, although maintenance records were not available to document if the mileage was original. The brakes were hydraulic drum in the front and rear, and no records were available to verify the last mechanical inspection or replacement of the brakes. The fire department had utilized the county maintenance department to perform work on all fire apparatus and a limited number of records were found for other apparatus, but none were found for the apparatus involved in this incident. There were no vehicle check-off records for the involved apparatus. Apparatus at the main station would be checked for deficiencies approximately weekly, but no formal records of these checks were kept. The apparatus in this incident was stored in a single bay fire station approximately 2 miles from the main station and was not regularly inspected or provided with any scheduled maintenance. The state of Georgia does not require annual vehicle inspections for fire apparatus, and the truck involved in this incident had never received a state inspection.

The driver of the apparatus reported brake failure just prior to the crash. The reported brake failure involved the brake pedal going completely to the floor with no resistance. Georgia state police investigators determined that the master brake cylinder was empty of hydraulic brake fluid after the crash, but did not determine if or where the brake fluid leaked from. The driver reported that steering the truck was difficult due to the front end shaking considerably. The driver had experienced this difficulty in steering the truck on previous occasions and had attributed this shaking to flat spots on the tires from the truck sitting for extended periods.

The last documented or known movement of the truck prior to this incident was on January 1, 2009, and no problems with the apparatus were reported or noted on the incident report. No fire fighters had reported any problems with the brakes or steering. There was no evidence of brake fluid on the station bay floor on the day of the NIOSH site visit, but there was evidence of motor oil leakage from the engine area. There were no braking assist systems installed on the apparatus.

b Manual transmissions come in two basic types: nonsynchronous or sliding-mesh, where gears are spinning freely and must be synchronized by the operator using engine revolutions (and double clutching) to match road speed to prevent gear clash or grinding; and synchronized systems or constant-mesh, which eliminate this necessity while changing gears.

TRAINING/EXPERIENCE

The driver in this incident had 2 years experience as a volunteer fire fighter with this department. The driver held a valid class B commercial driver’s license from the state of Georgia and had attended a driver training program (1-day class) that required successful completion of a practical cone course. The driver also had completed the state of Georgia Basic Fire Fighter Module 1 consisting of Basic Fire Fighter Level 1 classes that met the requirements of the Georgia Fire Fighter Standards and Training Council for a volunteer fire fighter. The driver had driven the apparatus involved in this incident in an emergency response on one other occasion and a few other nonemergency situations. He had driven other fire trucks at the station on 5 or 6 emergency incidents.

The victim (passenger) in this incident had approximately 3 years experience at this department and had completed the state of Georgia Basic Fire Fighter Module 1 training consisting of Basic Fire Fighter Level 1 classes that met the requirements of the Georgia Fire Fighter Standards and Training Council for a volunteer fire fighter.

The department required that all new members successfully complete module 1 training of the Georgia Basic Fire Fighter Course for volunteer fire fighters and a live-fire course before being allowed to participate in fire fighting activities.

ROAD AND WEATHER CONDITIONS

The engine was traveling on a two-lane blacktop state highway with a posted speed limit of 55 mph. The incident occurred at an intersection with a railroad crossing and a divided four-lane highway with two traffic signals (see Photo 2). The road surface was asphalt in good condition and was dry. At the time of the crash it was daylight, the skies were clear, visibility was 10 miles, and the temperature was 55°F. Winds were 7 mph, from the north.1

SEAT BELT LAWS

The state of Georgia exempts passenger vehicles performing an emergency service from seat belt laws. Georgia State Police confirmed that fire fighters are not required by law to wear seat belts. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration [49 CFR 390.3(f)(5)] also exempts the occupants of fire trucks and rescue vehicles from wearing seat belts while involved in emergency and related operations.

INVESTIGATION

On February 23, 2009, a 34-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured and another fire fighter (the driver) was seriously injured in a fire truck rollover crash. The driver and the victim were not wearing seat belts. The victim died from his injuries at the scene, and the driver was transported to the hospital with serious injuries and was hospitalized for 5 days. The crash occurred at approximately 1558 hours as the fire truck (E-4) was responding to a reported out-of-control brush fire. The crash occurred when E-4 was unable to stop while crossing an intersection, swerved to avoid traffic, and overturned into a utility pole.

The department had been alerted to respond to a brush fire reported to be out of control. Two fire trucks were dispatched from the department, one from the main station and E-4 from a remote station approximately 2 miles away. The driver of E-4 responded in his privately owned vehicle (POV) to the fire station, opened the bay door, and started the truck. E-4 (1964 commercial chassis “fire knocker”) was reported to be very “cold natured” and required the driver to maintain pressure on the accelerator to keep the truck running. The driver then pulled E-4 out of the station and onto the ramp and noticed the victim arriving in his POV. The victim got into the passenger seat and E-4 left the station.

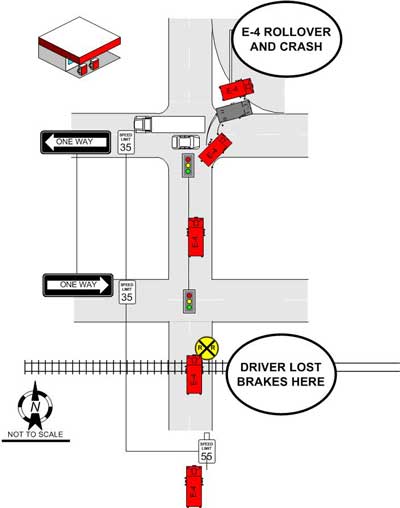

The driver stated during interviews that the truck was traveling approximately 45 mph when they approached the intersection. E-4 was responding code 3 (lights and siren) and had traveled 1½ miles when the driver attempted to apply the brakes, pushing the brake pedal all the way to the floor of the truck with no resistance. The driver told the victim that he didn’t have any brakes and the victim replied “do what you have to do” and took over activating the siren. The driver attempted to activate the brakes without success by pumping the brake pedal. He also attempted to slow the truck by down-shifting the transmission but was unable to shift into a lower gear. The driver reported that the two sets of traffic lights were turning from yellow to red in his direction. E-4 made it through the first set of lights at the crossing (see Photo 2) and noticed traffic at the next set of lights starting to move into the intersection. The driver swerved to the right of the traffic, lost control of the truck, and overturned into a utility pole (see Photos 3, 4 and Diagram).

The other responding apparatus came upon the overturned fire truck wreckage and requested assistance. The victim was pronounced dead at the scene and the driver was transported by emergency medical services to a local hospital.

There were no apparent skid marks on the roadway at the approach to the first traffic light or the second intersection. Yaw marks (see Photo 4) at the second intersection indicate the vehicle was moving in a direction to the right of center in the intersection before overturning.

Georgia state police investigators determined that the fire truck was traveling at 53 mph at the time of the crash. During an examination of the wreckage, state police investigators determined the brake master cylinder on E-4 was empty of fluid. The brakes on the front and rear axles had brake linings within the minimum requirements, and no evidence was found of wheel cylinder failure or leakage. A fire department representative performed a self-check of the brakes at the impound yard and verified that the master brake cylinder was empty and there was no resistance in the brake pedal.

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- Nonuse of seat belts. The department did not have a seat belt policy and neither the victim nor the driver were wearing their seat belts at the time of the crash.

- Inadequate programs to provide for the inspection, maintenance, and testing of fire apparatus.

- Inadequate driver training and driver inexperience with this specific fire apparatus. This incident was the second emergency response for the fire fighter driving this truck.

- An older apparatus with minimal safety features. This fire apparatus was purchased new in 1964 and did not have safety features that are standard on newer apparatus, such as automatic transmissions, disc brakes, traction control systems, and three-point seat belts.

- Emergency response code. Emergency response code 3 (lights and siren) was used when a non-emergency response should have been used considering the mechanical conditions and the designed auxiliary role of the apparatus.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The cause of death was reported by the coroner as trauma to the head.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure standard operating procedures (SOPs) regarding seatbelt use are developed and enforced.

Discussion: The fire department involved in this incident did not have a standard operating procedure (SOP) requiring the use of seat belts. The victim and the driver were not wearing seat belts at the time of the crash. Fire departments should develop and enforce SOPs on the use of seat belts. The SOPs should apply to all persons driving or riding in all emergency vehicles, and they should state that all persons should be seated and secured in an approved riding position before the vehicle is in motion.

Vehicle crashes are the second leading cause of fire fighter line-of-duty deaths. The driver/operator must always insure the safety of all personnel riding on the apparatus. Drivers should not move fire apparatus until all persons on the vehicle are seated and secured with seat belts in approved riding positions.2 Seat belts are not only important for protecting occupants in the event of a crash, but they may be useful in helping to avoid crashes. The U.S. Fire Administration’s Safe Operation of Fire Tankers states, “Some crash reconstruction specialists have speculated that particular incidents may have occurred after the unrestrained driver of a truck was bounced out of an effective driving position following the initial contact with a bump in the road or another object.”3

A seat belt policy that is not followed and/or enforced by fire department personnel does not achieve the benefit of the safety device. To increase the use of seat belts by fire fighters, the National Fire Service Seat Belt Pledge Campaign was created.4 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, United States Fire Administration, International Association of Fire Chiefs, National Volunteer Fire Council, NFPA, and National Fallen Fire Fighters Foundation all support the campaign as a method of raising awareness of the importance of mandatory use of seat belts by all fire fighters. Fire fighters wearing seat belts are an essential component of efforts to ensure the safety of fire fighters in fire apparatus and vehicles.5 Fire fighters who take the pledge and fire departments who achieve 100% pledge participation show their individual and organizational commitment to fire fighter safety.6 The International Association of Fire Chiefs has guidance on developing SOPs for emergency vehicle safety.7

Recommendation #2 Fire departments should ensure that programs are in place to provide for the inspection, maintenance, testing, and retirement of automotive fire apparatus.

Discussion: NFPA 1911, Standard for the Inspection, Maintenance, Testing, and Retirement of In-Service Automotive Fire Apparatus, states that fire apparatus should be serviced and maintained to keep them in safe operating condition and ready for response at all times.8 Maintenance schedules should be established and recorded as an integral part of a well-planned maintenance program. The maintenance program should include daily, weekly, and periodic maintenance service checks. The maintenance checks should be based on the manufacturer’s service manuals, the tire manufacturer’s recommendations, local experience, and operating conditions.

In this incident, the brakes failed while the apparatus was responding to an emergency call causing the driver to lose control, overturn, and crash into a utility pole. The department did not have a policy for inspection, maintenance, testing and retirement of the fire apparatus. It is likely that the lack of brake fluid in the master brake cylinder and the abnormal wear on the right front tire would have been detected and the truck placed out of service if an inspection and maintenance program was in place prior to the crash. The fire apparatus was over 40 years old, and lacked safety features normally found on more modern trucks. Braking systems, braking assist devices, drive trains, steering and suspension systems, and other safety systems were not present. The low volume of calls and activity and the likelihood of many different drivers responding in the vehicle increased the need for a comprehensive vehicle inspection and maintenance program.

The department did not keep records of maintenance performed on the apparatus involved in this incident. Proper record keeping provides many benefits to the safety of personnel and the ability of the fire department to estimate, predict, and fund equipment maintenance and replacement costs. Lack of proper record keeping can contribute to the inability to measure effectiveness and efficiency of maintenance programs that are designed to keep apparatus safe.

The state of Georgia does not require annual vehicle safety inspections for fire apparatus, and the fire department did not have a program for vehicle inspections. Complaints regarding vehicle performance or concerns regarding maintenance items in this department were supposed to be forwarded verbally to the county district chief who would arrange for repair. A comprehensive vehicle inspection, maintenance, and testing program should also include a formal method to place apparatus out of service and notify any potential responders of the unit’s status.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should provide and ensure all drivers successfully complete a comprehensive driver’s training program such as NFPA 1451, Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program, before allowing a member to drive and operate a fire department vehicle.

Discussion: Fire departments should provide adequate resources and training to ensure that the safe arrival (and return from) an emergency scene is their first priority. Fire departments should develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures and ensure fire fighters are thoroughly trained and qualified before being allowed to drive and operate emergency vehicles. The minimum requirements for a fire service vehicle operations training program are contained in NFPA 1451, Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program. The objective of the training program is to prevent crashes, injuries, and fatalities (both civilian and fire service) involving fire service vehicles. Fire departments must also ensure that fire fighters are familiar with all of the different models of fire apparatus that they may be expected to operate. The members should be trained to operate specific vehicles or classes of vehicles before being authorized to drive or operate such vehicles.9 A driver training program should include instruction for the driver(s) to identify mechanical issues during vehicle check offs that would necessitate taking the vehicle out of service immediately or reporting concerns through a formal process. A combination of inexperience in this class of vehicle and lack of training were factors that may have contributed to this incident.

In this incident, the driver of the truck had only 2 years of experience as a volunteer fire fighter and had only driven this truck on one other emergency response. During an interview with a NIOSH investigator, the driver noted that the truck had a very rough ride and would “shake the truck bad.” A benefit of experience and training on an apparatus is being able to differentiate between general operating characteristics of the apparatus from a symptom of a larger mechanical issue affecting steering and braking. Fire fighters had reported that the truck was hard to start, very cold natured, and required the driver to “feather the gas” to keep the engine running when first started. The driver’s potential preoccupation with keeping the engine running (“feathering the gas”) while disengaging the clutch may have resulted in his not applying the brakes on the station ramp which was his practice of checking the brakes before leaving the station. A disadvantage of a manual transmission is that the driver cannot maintain two hands on the steering wheel at all times. A manual transmission can be especially problematic for inexperienced drivers who may not adapt to changing road conditions or notice mechanical or handling characteristics because of their focus on shifting gears. Fire departments should be explicit with SOPs and driver training regarding emergency response driving and ensure operators are trained to perform a pre-trip inspection that includes checking the brakes before responding in an apparatus that has been sitting unstaffed for extended periods of time.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should consider replacing fire apparatus more than 25 years old.

Discussion: In this incident, the fire apparatus was more than 40 years old, and because of a very low department call volume, the truck was not driven regularly. Even if the driver had tested the brakes when pulling out of the station and they were found to be operating properly, the lack of a proper preventive maintenance program and extreme age of the apparatus may not have provided sufficient safeguards to insure proper braking ability or a safe emergency response. Newer apparatus have designs that improve the stopping power of the braking system. Antilock disc braking on all axles and additional braking assist devices, such as engine brakes, have made heavy fire apparatus safer for responding fire fighters.

To maximize fire fighter safety as well as the safety of the traveling public, it is important that fire apparatus be equipped with the latest safety features and operating capabilities. In the last 15 to 20 years, much progress has been made in upgrading the safety features and capabilities of fire apparatus. Significant improvements in fire apparatus safety have been the standard since 1991, and fire departments should consider the value (or risk) to fire fighters of keeping pre-1991 fire apparatus in first-line service. Apparatus manufactured prior to 1991 usually conformed to only a few of the safety standards for fire apparatus set by the NFPA.10

The length of a vehicle’s life depends on many factors, including mileage and engine hours, quality of the preventive maintenance program, quality of the driver training program, whether the fire apparatus was used within the design parameters, whether the apparatus was manufactured on a custom or commercial chassis, quality of workmanship by the original manufacturer, quality of the components used, and the availability of replacement parts, to name a few.10

Fire departments should consider upgrading older fire apparatus in accordance with NFPA 1912, Standard for Fire Apparatus Refurbishing, latest edition,11 and retire or replace older apparatus in accordance with current standards such as NFPA 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus10. Fire departments should also consider retiring apparatus sooner if the apparatus becomes obsolete or unreliable due to age or use.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should consider downgrading the emergency response code for auxiliary fire apparatus such as brush fire support vehicles.

Discussion: Fire departments should consider developing programs using a risk benefit analysis to prioritize emergency vehicle response by auxiliary or fire support vehicles. Many auxiliary apparatus do not have the same safety features as standard Class A pumpers which are built to current NFPA specifications. These apparatus include brush fire fighting apparatus and other auxiliary support function units such as tanker/tenders. The specific needs of brush fire fighting units and support units may require greater ground clearance, larger tires, four-wheel drive, and large water-carrying capacity. Many of the requirements for off-road, brush fire fighting and large water-carrying capacity also cause greater difficulty in on-road handling due to the raised center of gravity and the common handling problems associated with the specific-duty apparatus. Often, these apparatus are older, infrequently used, and not designed for higher-speed response on roadways.

In this incident, the fire apparatus was a 1964 commercial chassis with a 1,000-gallon tank and a pump with 2 hose reels on the rear. The truck was infrequently used, and although it appeared to have low mileage, it was not inspected regularly and could not be relied upon to safely respond in an emergency mode. Fire departments should develop programs that measure the risk benefit of using these apparatus in relationship to the response code to insure the safety of the fire fighters who respond on the apparatus as well as other motorists on the roadways.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should be aware of programs that provide assistance in obtaining alternative funding, such as grant funding, to replace or purchase fire apparatus and equipment.

Discussion: While it is important that fire departments seek constant improvements and upgrades to their fire apparatus and equipment, some departments may not have the resources or programs to replace or upgrade their apparatus and equipment as often as they should. Alternative funding sources, such as federal grants, are available to purchase fire apparatus and equipment. Additionally, there are organizations that can assist fire departments in researching, requesting, and writing grant applications. Useful resources include:

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Assistance to Firefighters Grant (AFG) Programexternal icon

www.firegrantsupport.com

FEMA grants are awarded to fire departments to enhance their ability to protect the public and fire service personnel from fire and related hazards. This Web site offers resources to help fire departments prepare and submit grant requests.

FEMA, Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) Grants

www.firegrantsupport.com/safer/ (Link no longer available 5/13/2015)

SAFER grants provide funding directly to fire departments and volunteer firefighter interest organizations to help them increase the number of trained, front-line fire fighters in their communities and to enhance the local fire departments’ abilities to comply with staffing, response, and operational standards established by NFPA and Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), Safer Act Grantexternal icon

www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/standards-development-process/safer-act-grant

NFPA provides excerpts from NFPA 1710 and NFPA 1720 and other online resources to assist fire departments with the grant application process. (Link updated 8/13/2013)

National Volunteer Fire Council (NVFC), Grants & Fundingexternal icon

http://www.nvfc.org/hot-topics/grants-funding (Link Updated 4/9/2013)

The NVFC provides an online resource center to assist departments applying for SAFER grants, including narratives from successful past grant applications and a listing of federal grant and funding opportunities.

FireGrantsHelp.comexternal icon

www.firegrantshelp.com

A nongovernmental group, FireGrantsHelp.com provides an extensive database of information on federal, state, local, and corporate grant opportunities for first responders.

The primary goal of the Assistance to Fire Fighters Grant (AFG) Program is to provide critically needed resources such as emergency vehicles and apparatus, equipment, protective gear, training for responders, and other needs to help fire departments protect the public and emergency workers from fire and related hazards. The Grant Programs Directorate of FEMA administers the grants in cooperation with the United States Fire Administration.

Recommendation #7: Federal and state departments of transportation should consider modifying or removing exemptions that allow fire fighters to not wear seatbelts.

Discussion: The July/August 2007 issue of NFPA Journal, Firefighter Fatalities Studies 1997–2006,12 states, “In 1987, the first edition of NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health program, was issued with requirements that all firefighters riding on fire apparatus be seated and belted any time the apparatus is in motion. That same year, a Tentative Interim Amendment to NFPA 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus, required the provision of seats and seat belts for the maximum number of persons who are going to ride on the apparatus.” The journal noted that in a 30-year study of fire fighter fatalities, the second largest share of fire fighter deaths occurred from crashes. Of the 406 victims, 76% were known not to be wearing seatbelts.

The state of Georgia exempts passenger vehicles providing emergency services from using seat belts. Georgia State Police confirmed that fire fighters are not required by law to wear seat belts. The Federal Motor Carrier Administration regulations provide exemptions for fire and emergency vehicle responders regarding seat belt use as well. Federal and state departments of transportation should consider modifying or removing the exemptions for fire fighters based on the large number of fire fighter deaths associated with non use of seatbelts, and to be more consistent with best practices. Federal and state seat belt laws should be in agreement with consensus standards such as NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, which require all fire fighters to be seated and belted while the vehicle is in motion 2.

REFERENCES

- Weather Underground [2009]. Weather history for Georgiaexternal icon, February 23, 2009. [www.wunderground.com/history/airport/KVAD/2009/2/23/DailyHistory.html] Date Accessed: June 17, 2009.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500 standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- FEMA [2004]. Safe operation of fire tankers. Emmitsburg, MD: Federal Emergency Management Agency, FA-248.

- TrainingDivision.com [2009]. NFS International seat belt pledge [www.trainingdivision.com/seatbeltpledge.asp]. (Link no longer available 1/9/2012) Date accessed: February 2009.

- FEMA [2008]. NIOSH supports seat belt use by fire fighters. Press releaseexternal icon, November 18, 2008 [www.usfa.fema.gov/media/press/2008releases/111808.shtm]. (Link Updated 1/9/2012) Date accessed: February 2009.

- USFA [2009]. Seatbelts: enough is enough. Buckle upexternal icon [www.usfa.fema.gov/about/chiefs-corner/071708.shtm]. (Link Updated 1/9/2012) Date accessed: February 2009.

- IAFC [2009]. Guide to model policies and procedures for emergency vehicle safety.external icon June 29, 2009. [www.iafc.org/Operations/content.cfm?ItemNumber=1374]. (Link Updated 1/9/2012) Date accessed: June 30, 2009.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1911 standard for the inspection, maintenance, testing, and retirement of in-service automotive fire apparatus, 2007 edition. Annex D guidelines for first-line and reserve fire apparatus. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1451 standard for a fire service vehicle operations training program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2009]. NFPA 1901 standard for automotive fire apparatus. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2006]. NFPA 1912 standard for fire apparatus refurbishing. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Fahy R, LeBlanc P, Molis J [2007]. Firefighter fatalities studies 1977–2006: what’s changed over the past 30 years? NFPA Journal. July/August 2007:4–5.

- Virginia Commonwealth University Transportation Safety Training Center [2009]. Tips: yaw mark analysisexternal icon [www.vcu.edu/cppweb/tstc/tips/index]. Date accessed: June 30, 2009.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by Stephen T. Miles, Occupational Safety and Health Specialist with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH. An expert technical review was conducted by Dr. Burton A. Clark, EFO, CFO, National Fire Academy, and Kevin Roche, Assistant to the Fire Chief, Phoenix Fire Department. Assistance with vehicle information was provided by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

PHOTOS AND DIAGRAMS

|

|

Photo 1. Right front tire tread indicating needed maintenance of steering system and replacement of the tires. |

|

|

Photo 2. Driver’s view of roadway at the railroad crossing where E-4’s brakes failed entering the intersection. Traffic began to enter the 2nd intersection from the right after E-4 passed through the 1st traffic light. (NIOSH photo) |

|

|

Photo 3. E-4 against utility pole. |

|

|

Photo 4. Road markings just before rollover. Note “yaw” marks on roadway. Marks on the right are from the front tires and marks on the left are from the rear tires just prior to the rollover. Tire yaw marks occur when a vehicle slides sideways while still moving forward. In a true yaw, where the vehicle’s rear is attempting to pass the vehicle’s front, each rear tire tracks outside the corresponding front tire.13 |

|

|

Diagram. E-4’s path of travel after driver realized he had no brakes at rail road crossing. |

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In fiscal year 1998, the Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative. NIOSH initiated the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program to examine deaths of fire fighters in the line of duty so that fire departments, fire fighters, fire service organizations, safety experts and researchers could learn from these incidents. The primary goal of these investigations is for NIOSH to make recommendations to prevent similar occurrences. These NIOSH investigations are intended to reduce or prevent future fire fighter deaths and are completely separate from the rulemaking, enforcement and inspection activities of any other federal or state agency. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the deaths in order to provide a context for the agency’s recommendations. The NIOSH summary of these conditions and circumstances in its reports is not intended as a legal statement of facts. This summary, as well as the conclusions and recommendations made by NIOSH, should not be used for the purpose of litigation or the adjudication of any claim. For further information, visit the program website at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

|

This page was last updated on 08/27/09.