Volunteer Fire Fighter is Killed and Another Volunteer Fire Fighter is Injured at a Wildland/Urban Interface Fire - Oklahoma

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2006-10 Date Released: August 7, 2007

SUMMARY

On March 1, 2006, a volunteer fire fighter (the victim) was critically injured and another volunteer fire fighter was seriously injured while fighting a wildland/urban interface fire. The two fire fighters arrived on the scene at approximately 1600 hours as the fire jumped a paved road and began to burn in a field between two homes. The fire was rapidly spreading in an easterly direction toward a large pasture when the victim drove the grass truck into the field to conduct a direct attack on the south flank of the fire. The victim drove the grass truck while the other fire fighter attacked the fire using a hose line while riding in the bed of the truck. The victim instructed the fire fighter that they had to leave the area due to the limited visibility caused by the heavy smoke conditions. The fire fighter began to secure the hose line in the bed of the truck when he felt an increase in heat from the advancing fire. The victim put the grass truck in reverse and inadvertently backed the truck into a ditch where the fire fighter fell out of the bed of the truck and became entangled in a barbed wire fence. The fire burned over their position, destroying the grass truck, critically injuring the victim, and seriously injuring the fire fighter. The fire fighter freed himself from the barbed wire, located the incapacitated victim in the thick smoke, and told him that he was going to get help. The fire fighter was walking toward the paved road when he flagged down a tender with two fire fighters inside. He told them about the victim’s condition and then sent them across the field to help him. The victim was transported in the tender back to the paved road where an ambulance was waiting to transport him to an area hospital. The victim was air lifted at 1836 hours to the State Burn Center. The injured fire fighter was transported to the regional hospital where he was treated for 2nd and 3rd degree burns to his hands, face, and lower back before being released later that same day. The victim died on March 24, 2006, as a result of the injuries he received on March 1, 2006.

|

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that wildland fire fighting crews check-in at the Incident Command Post, staging area or with the Division/Group Supervisor and obtain a briefing and assignment prior to engaging in fire fighting activities

- ensure that all fire fighters expected to participate in wildland fire fighting operations receive training equivalent to the NFPA Wildland Fire Fighter Level I

- provide fire fighters with approved fire shelters and provide training on the proper deployment of the fire shelters at least annually, with periodic refresher training

- provide fire fighters with wildland appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., Nomex® pants or coveralls) that is NFPA 1977 compliant

- ensure that personnel engaged in wildland fire fighting follow the guidelines addressed in the Fireline Handbook developed by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group

- establish, implement, and enforce procedures which include, but are not limited to, combating ground cover fires

INTRODUCTION

On March 1, 2006, a volunteer fire fighter (the victim) was critically injured and another volunteer fire fighter was seriously injured while fighting a wildland/urban interface fire. On March 28, 2006, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On May 8-10, 2006, two Safety and Occupational Health Specialists from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. Meetings were conducted with the County Fire Chief, the Fire Chief from the victim’s Career Fire Department and the Fire Chief from his Volunteer Fire Department, County Safety Officer, Regional Director of Public Safety, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Coordinator from the Oklahoma Fire Center. Interviews were conducted with the injured fire fighter, the Fire Chief from the city threatened by the advancing fire, the driver of a tender operating in the area of the fatal site, and the Fire Control Officer from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) assigned to the region where the fatal incident occurred. The investigators reviewed the victim’s training records, autopsy report and death certificate, the Incident Action Plan (IAP), the BIA wildland fire management cooperative intergovernmental agreement, the Oklahoma fire danger model produced for the day of the incident, the recorded weather data for the month of March 2006, the Fire Entrapment Report produced by the Accident Review Team, the County Fire Service Board’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), mutual-aid agreement between the two counties involved in this incident, and the list of available emergency radio frequencies. The incident site was visited and photographed.

Fire Department

This volunteer department consists of approximately 25 fire fighters operating out of 1 fire station that serves a population of about 2,500 in a geographic area of approximately 91 square miles.

Training and Experience

The victim had over 7 years of combined service. He worked as a fire fighter-paramedic with a career department. He had over 2 years of experience with this volunteer fire department and had completed an extensive list of training courses during his career which included: Fire Fighter I, Flashover Training, Emergency Medial Services, Hazardous Materials Operator, and Apparatus Operator.

Equipment and Personnel

1995 1 ton 4X4 flatbed truck modified with 400-gallon tank and class 9 pump with 100 feet of 1-inch line and 100 feet of 1 ½ inch line. (Two fire fighters – A driver (victim) and a passenger (injured)).

The fire fighters were providing mutual aid to another volunteer fire department that had made a request to “send all the help you can” through central dispatch. The request was made again over the State Fire Channel for “all available hands”.

Personal Protective Equipment

The victim was wearing bunker pants, nylon hiking boots, and a tee shirt. He was not wearing his bunker coat, helmet, fire boots, or gloves. The injured fire fighter was wearing his full bunker gear, fire boots, helmet, and nomex hood. He was not wearing any gloves. Neither fire fighter had a fire shelter.

Weather Conditions and Fire Behavior

Fire weather on March 1, 2006 was extreme. During the time of the entrapment (1600-1700 hours), the predicted rate of spread (ROS) was 196 (2.5 mph); flame length 7 feet, and spotting distance 0.3 miles. Wind gusts consistently maximized the ROS for this fuel model at 446 chains per hour (5.6 mph) with 10-foot flame lengths from the initial fire report until 1700 hours.

INVESTIGATION

On March 1, 2006, at approximately 1110 hours, two volunteer fire fighters were dispatched separately to a grass fire (not the fatal incident). The victim responded in a Grass truck and the injured fire fighter responded in a Tender. The two fire fighters arrived at the staging area where they waited until approximately 1400 hours when they were released from staging. The victim drove the grass truck and the injured fire fighter drove the tender back to their station.

At approximately 1500 hours, the two fire fighters were dispatched to provide mutual-aid assistance for a reported structure/grass fire. The victim, who was driving, responded with the injured fire fighter in the grass truck. The two fire fighters arrived at the mutual-aid department and were released without an assignment.

At approximately 1530 hours, the two fire fighters were directed by their Fire Chief to provide mutual aide to another volunteer department and respond to a reported grass fire, located approximately 25 miles to the south of their fire station. While en-route, the victim and injured fire fighter heard a dispatch message on the State Fire Channel for “all available hands” for the grass fire they were responding to (the grass fire where the fatal event occurred). Neither the victim nor the injured fire fighter acknowledged the call due to the heavy volume of radio traffic. The two fire fighters, approximately 20 miles from the incident site, could see the smoke from the fire.

The victim and injured fire fighter arrived at the fire at approximately 1600 hours where they encountered a group of fire fighters along the road. The victim asked the group of fire fighters where staging was located. One of the fire fighters informed them that it was just down the road. Another fire fighter then told them to “find some fire and fight it”. The victim and injured fire fighter couldn’t see any fire, just smoke. They assumed that the fire was spreading in an easterly direction, the same direction as the grass fire they had responded to earlier in the day.

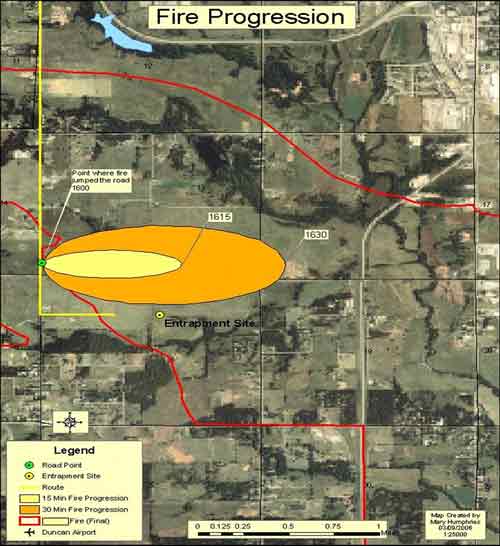

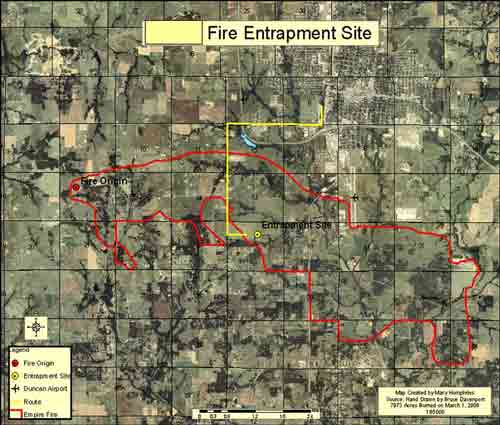

The two fire fighters proceeded down the road, heading south, where they saw a crew in the field on the east side of the road (south flank of the fire). Note: The fire had jumped the paved road, was burning in a field between two homes and was rapidly spreading in an easterly direction toward a large pasture. The two fire fighters proceeded a few hundred yards farther down the road where they encountered a private citizen who informed them that the fire fighters were accessing the field through his property, on the east side of the road. As the two fire fighters entered the field they saw a tender on the east side of the road just to the north of their position. The two fire fighters could see very heavy smoke with some fire. The victim drove the grass truck through the field (heading east) toward a gate located on a fence that ran in a north/south direction (Diagram 1). The victim drove the grass truck through the gate and into the pasture where they began to conduct a direct attack on the south flank of the fire (Photo1). The victim drove the grass truck while the other fire fighter attacked the fire using a hose line while riding in the bed of the truck. They knocked down some of the fire and the victim drove the grass truck into the “black” or area already burned. The victim instructed the fire fighter that they had to leave the area due to the limited visibility caused by the heavy smoke conditions. The fire fighter began to secure the hose line in the bed of the truck when he felt the heat from the advancing fire on his back. The victim put the grass truck in reverse and inadvertently backed the truck into a ditch (Photo 2). The fire fighter fell out of the bed of the truck from the force of the truck striking the ditch and became entangled in a barbed wire fence.

|

Photo 1. Example of fuel from same field where the incident occurred |

|

Photo 2. Re-creation of how grass truck was positioned during burn-over incident. |

The fire burned over their position, destroying the grass truck, critically injuring the victim and severely injuring the fire fighter entangled in the barbed wire. The injured fire fighter’s hand had been badly burned but he was able to free himself from the barbed wire and locate the victim who was away from the truck in the thick smoke. The fire fighter told the incapacitated victim that he was going to go get help. The fire fighter walked back toward the paved road where he saw a tender with two fire fighters inside. He flagged them down and he sent them across the field to help the victim. The victim was transported in the tender back to the paved road where an ambulance was waiting to transport him to an area hospital. The victim was air lifted at 1836 hours to the state burn center. The injured fire fighter was transported to the regional hospital where he was treated for 2nd and 3rd degree burns to his hands, face, and lower back before being released later that same day. The victim died, as a result of his burn injuries, on March 24, 2006.

|

Diagram 1. Courtesy of USDA, Forest Service |

|

Diagram 2. Courtesy of USDA, Forest Service |

Cause of Death

The victim died 21 days after the incident due to complications from the burns he received to over 45% of his body.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that wildland fire fighting crews check-in at the Incident Command Post, staging area or with the Division/Group Supervisor and obtain a briefing and assignment prior to engaging in fire fighting activities.

Discussion: Fire departments should develop guidelines and train their fire fighters to follow procedures established by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group, Fireline Handbook, for Check-in Procedures at an incident. There may be several locations for incident check-in. Check-in officially logs you in at the incident and provides important release and demobilization information. Fire fighters only check in once. Check-in records may be found at the following locations:

- Incident Command Post

- Base or Camp

- Staging Area

- Helibase

- If you are instructed to report directly to a line assignment, you should check-in with the Division/Group Supervisor.

After check-in, locate your incident supervisor and obtain your initial briefing. The items you receive in your briefing, in addition to functional objectives, will also be needed by your subordinates in the briefing. The items include:

- Identification of specific job responsibilities expected of you for satisfactory performance

- Identification of co-workers within your job function

- Definition of functional work area

- Identification of eating and sleeping arrangements

- Procedural instructions for obtaining additional supplies, services and personnel

- Identification of operational period work shifts

- Clarification of any important points pertaining to assignments that may be questionable

- Provisions for specific debriefing at the end of an operational period

- A copy of the Incident Action Plan

- Use available “waiting time” to refresh training, improve organization and communications, and check equipment.1

Recommendation #2 : Fire departments should ensure that all fire fighters expected to participate in wildland fire fighting receive training equivalent to the NFPA Wildland Fire Fighter Level I.

Discussion: In order for fire fighters to be effective and to remain safe on the fire line, adequate training is paramount. NFPA 1051, identifies requisite knowledge for wildland fire fighters including fireline safety, use, and limitations of personal protective equipment, agency policy on fire shelter use, basic wildland fire behavior, fire suppression techniques, basic wildland fire tactics, the fire fighter’s role within the local incident management system, and first aid.2

Recommendation #3 : Fire departments should provide fire fighters with approved fire shelters and provide training on the proper deployment of the fire shelters at least annually with periodic refresher training.

Discussion: According to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s Fireline Handbook, firefighting safety guidelines, fire shelters should always be carried when on the fire line. Fire shelters are crucial pieces of safety equipment for wildland fire fighting. The shelter is an effective, life saving device that allows fire fighters to protect themselves should they be overrun by a fire with no option for escape. Training should emphasize, however, that fire shelters are intended to be deployed only as a last resort to survive a fire entrapment. All other reasonable means of escaping the fire should be attempted before deploying the shelter. 1,3

Recommendation #4 : Fire departments involved in wildland fire fighting should provide fire fighters with wildland appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., Nomex® pants or coveralls) that is NFPA 1977 compliant.

Discussion: Volunteer fire fighters provide invaluable services to communities across the nation; therefore, the safety and health of fire fighters should be of overriding importance. Fire fighters involved in wildland fire-fighting activities should be provided, at a minimum, the PPE as described by NFPA 1977 to perform these activities safely. Also, if funds are unavailable within the volunteer fire department to purchase the appropriate PPE, then State and local community representatives should consider ways to secure funding necessary to equip every volunteer fire fighter with appropriate PPE (e.g., flame retardant clothing, gloves, safety glasses, leather boots, etc.). In this case, it is uncertain whether PPE would have prevented this tragic death; however, if proper PPE had been used, the victim’s chances for survival would have been greater. 1, 4-5

Recommendation #5 : Fire departments should ensure that personnel engaged in wildland fire fighting follow the guidelines addressed in the Fireline Handbook developed by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group.

Discussion: The fundamental guidelines that are covered in the handbook are the foundation to wildland fire fighting safety. Personnel who are properly trained and involved in wildland fire fighting operations should follow these guidelines such as the 10 standard fire orders, the 18 watchout situations, and also establish lookouts, communications, escape routes and safety zones (LCES). 1

Recommendation #6 : Fire departments involved in wildland fire fighting should provide fire fighters with wildland appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., Nomex® pants or coveralls) that is NFPA 1977 compliant.

Discussion: The ability to “pump and roll” is a tremendous advantage when combating ground cover fires. Vehicles with the ability to pump and roll use a separate motor or a power take-off to power the pump. This arrangement enables the apparatus to be driven and discharge water on the fire at the same time as was the case in this incident. According to the International Fire Service Training Association (IFSTA), two methods are proper for making a moving fire attack: “The first is to have firefighters use a short section of hose and walk alongside the apparatus and extinguish the fire as they go,” and “the second is to use nozzles that are remotely controlled from inside the cab.” 6 Procedures should be established, implemented and enforced which prohibit fire fighters from fighting fires while positioned inside the bed of pickup trucks or on other types of apparatus.

REFERENCES

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group [1998]. NWCG fireline handbook 3. Boise, ID: National Wildfire Coordinating Group, common responsibilities, pp 72-73.

- National Fire Protection Association [2007]. NFPA 1051, standard for wildland fire fighter professional qualifications. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group [1998]. NWCG fireline handbook 3. Boise, ID: National Wildfire Coordinating Group, firefighting safety guidelines, p 42.

- International Fire Service Training Association [2003]. Wildland Fire Fighting for Structural Firefighters. Fourth Edition. Stillwater OK: Fire Protection Publications, Oklahoma State University, p. 131.

- National Fire Protection Association [2005]. NFPA 1977, standard on protective clothing and equipment for wildland fire fighting. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group [1998]. NWCG fireline handbook 3. Boise, ID: National Wildfire Coordinating Group.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Mark McFall, and Jay Tarley Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH.

This page was last updated on 08/07/07.