Temporal Trends of Acute Chemical Incidents and Injuries — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance, Nine States, 1999–2008

Surveillance Summaries

April 10, 2015 / 64(SS02);10-17Corresponding author: Perri Zeitz Ruckart, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, CDC. Telephone: 770-488-3808; E-mail: afp4@cdc.gov.

Abstract

Problem/Condition: Widespread use of hazardous chemicals in the United States is associated with unintentional acute chemical incidents (i.e., uncontrolled or illegal release or threatened release of hazardous substances lasting <72 hours). Efforts by industries, government agencies, academics, and others aim to reduce chemical incidents and the public health consequences, environmental damage, and economic losses; however, incidents are still prevalent.

Reporting Period: 1999-2008.

Description of System: The Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance (HSEES) system was operated by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) during January 1991-September 2009 to describe the public health consequences of chemical releases and to develop activities aimed at reducing the harm. This report summarizes temporal trends in the numbers of incidents, injured persons, deaths, and evacuations from the nine states (Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in HSEES during its last 10 full years of data collection (1999-2008).

Results: A total of 57,975 incidents and 15,506 injured persons, including 354 deaths, were reported. During the surveillance period, several trends were observed: a slight overall decrease occurred in incidents for fixed facilities (R2 = 0.6) and an increasing trend in deaths (R2 = 0.7) occurred, particularly for the general public (R2 = 0.9). The number of incidents increased in the spring during March-June, and a decrease occurred in the remainder of the year (R2 = 0.5). A decreasing trend in incidents occurred during Monday-Sunday (R2 = 0.7) that was similar to that for the number of injured persons (R2 = 0.6). The highest number of incidents occurred earlier in the day (6:00 a.m.-11:59 a.m.) and then decreased as the day went on (R2 = 0.9); this trend was similar for the number of injured persons (R2 = 1.0).

Interpretation: Chemical incidents continue to affect public health and appear to be a growing problem for the general public. The number of incidents and injuries varied by month, day of week, and time of day and likely was influenced by other factors such as weather and the economy.

Public Health Implications: Public and environmental health and safety practitioners, worker representatives, emergency planners, preparedness coordinators, industries, emergency responders, and others can use the findings in this report to prepare for and prevent chemical incidents and injuries. Specifically, knowing when to expect the most incidents and injuries can guide preparedness and prevention efforts. In addition, new or expanded efforts and outreach to educate consumers who could be exposed to chemicals are needed (e.g., education about the dangers of carbon monoxide poisoning for consumers in areas likely to experience weather-related power outages). Redirection of efforts such as promoting inherently safer technologies should be explored to reduce or eliminate the hazards completely.

Introduction

Hazardous chemicals are widely used in various industries and settings across the United States, and unintentional and illegal chemical releases can cause substantial morbidity and mortality (1). Public authorities at all levels, industries, academia, and others are involved in efforts to reduce the number of chemical incidents and associated injuries. These efforts include recommendations made from Chemical Safety Board investigations (2), targeted outreach by federal public health and safety agencies (3,4), the American Chemistry Council safety initiatives (5), and resources and tools provided by the Toxic Use Reduction Institute (6).

To assess whether outreach efforts resulted in reductions over time or whether patterns were detected in the numbers of incidents, injured persons, and deaths, time trend data from the federal Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance (HSEES) system among the nine states that continuously participated in the system for 10 years were evaluated. This information can be used to develop future outreach activities.

The HSEES database provides information on the characteristics and spatial and temporal dimensions of hazardous chemical releases within the states that participated in the surveillance system (7). This report summarizes temporal trends of acute (lasting <72 hours) chemical incidents and associated injuries experienced within 24 hours occurring in selected states during 1999-2008 and is a part of a comprehensive surveillance summary (8). Public and environmental health and safety practitioners, worker representatives, emergency planners, preparedness coordinators, industries, emergency responders, and others can use the findings in this report to prepare for and prevent chemical incidents and injuries.

Methods

This report is based on data reported to HSEES by health departments in nine states (Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in HSEES during its last 10 complete calendar years of data collection, 1999-2008. Data from 2009 were not included because several states ended data collection mid-year. A detailed description of the HSEES data used in this analysis is found elsewhere (8). Case definitions, exclusion criteria, and 2006 changes in reporting guidelines used for this analysis are described (Box).

Temporal trends in the numbers of incidents, injured persons, and deaths are described. Information collected for HSEES incidents included the time and date of occurrence; type of incident (fixed facility or transportation); location where the incident occurred; industry involved; area affected; proximity to vulnerable populations; chemicals released; number and type of injured persons, injuries, and deaths; evacuation details; and contributing factors for the incident.

In the analysis of deaths, single deaths in transportation incidents were not counted because they often are the result of trauma from a motor vehicle crash or rollover and not from a chemical exposure. Descriptive statistics and the coefficient of determination (R2, which indicates how well data fit a statistical model) are presented to assess linear trends in number of incidents, number of injured persons by population group, and number of deaths. Other temporal distributions of incidents and injuries (season, day, and time) also were examined.

Results

Number of Incidents

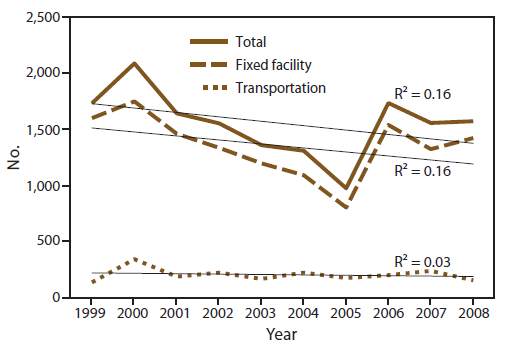

A total of 57,975 incidents occurred during 1999-2008; 41,993 (72%) occurred in a fixed facility, and 15,981 (28%) were transportation related. Incident type was missing for one incident. The total number of incidents varied, and the trend decreased overall (R2 = 0.3). This decrease was driven by fixed-facility incidents (R2 = 0.6) because of a slight upward trend that occurred in transportation incidents (R2 = 0.3) (Figure 1). The highest number of incidents occurred in 2002 (6,499), and the fewest occurred in 2005 (5,194). For each year, the percentage of incidents that occurred in fixed facilities was higher than the percentage that was transportation related.

Number of Injured Persons by Population Group

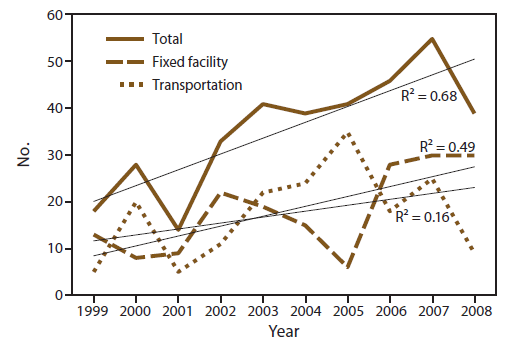

A total of 15,506 persons were injured; 13,502 were injured in fixed facilities, and 2,004 were injured in transportation-related incidents. The number of injured persons varied greatly over time, primarily because of fluctuations in fixed-facility incidents, and no overall trend was found (Figure 2). The average number of injured persons per year was 1,551. The majority of injured persons were employees (7,674), followed by members of the general public (4,737), students (1,730), and responders (1,340); the population group was unknown for 25 injured persons.

The trend for number of injured employees decreased slightly but was always higher than the other categories (R2 = 0.3) (Figure 3). The number of injured persons from the general public generally increased over time (R2 = 0.3). The number of injured responders decreased slightly (R2 = 0.5). The number of injured students was more variable.

Number of Deaths

A total of 354 deaths occurred during 1999-2008 (Figure 4); 180 deaths were in fixed facilities and 174 were transportation related. The average number of deaths per year was 35. A spike in transportation-related deaths occurred in 2006. The trend for deaths increased (R2 = 0.7), which was driven by incidents in fixed facilities (R2 = 0.5). An overall increase in deaths in the general public occurred (R2 = 0.9); no trends were found among employees or responders (Figure 5).

Trends in Month, Day, and Time of Incidents

The number of incidents increased in the spring during March-June, and a decrease occurred in the remainder of the year (R2 = 0.5) (Figure 6). The highest number of persons were injured in June (n = 1,683), and the fewest in December (n = 1,034); no trend was found. A decreasing trend in incidents occurred during Monday-Sunday (R2 = 0.7); this trend was similar for the number of injured persons (R2 = 0.6) (Figure 7). The highest number of incidents occurred earlier in the day (6:00 a.m.-11:59 a.m.) and then decreased as the day went on (R2 = 0.9) (Figure 8). Approximately half as many incidents occurred during other times of the day, which was similar for the number of injured persons as well (R2 = 1.0).

Discussion

A useful surveillance system collects and archives data that can be used to improve public health. States analyzed the collected data and developed appropriate prevention outreach activities. These activities were intended to provide various industries, responders, and the general public with information to help prevent chemical releases and to reduce morbidity and mortality should a release occur. Many different activities were conducted that were dependent on the state-identified problem areas (9).

During the surveillance period (1999-2008), the number of chemical incidents reported to HSEES varied by month, day of week, and time of day and likely was influenced by other factors such as weather and the economy. Overall, the number of incidents and injured persons have decreased slightly (primarily because of decreases in fixed-facility incidents) over the 10-year period. However, the number of fixed-facility incidents and injuries per year was always greater than the number for transportation-related incidents. Recent large incidents and the efforts of the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration and Chemical Safety Board have focused attention on worker safety (10,11). Whereas injuries and deaths among workers decreased, injuries and deaths in the general public increased. This increase might be partially attributable to an effort to obtain more notifications from medical centers, poison control centers, and the media. These sources differ from traditional HSEES notification sources and often include smaller-scale injuries that are not reported to state environmental departments, because many occur in the home to members of the public.

A seasonal trend was observed, with the number of incidents increasing during March-June, which coincides with the spring planting season in agricultural states (12). However, a seasonal trend in the number of injured persons did not occur. Although more incidents occurred and more persons were injured on weekdays than on weekends, the fewest number of weekday incidents and injured persons occurred on Mondays, the day operations normally resume or increase. The majority of incidents occurred during 6:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m., which covers the typical workday. Fewer incidents occurred and fewer persons were injured during the third shift, which might be attributed to times during which production is decreased and fewer people are working.

The fewest incidents per year occurred in 2005, the year that also had the fewest total number of injured persons, injured employees, injured responders, and injured students. More employees were injured every year than were any other population group; however, in 2005, only 16 more employees than members of the general public were injured.

The findings in this report appear to be weather related. Hurricane Katrina, which occurred on August 28, 2005, shut down oil pipelines and production facilities as well as transportation routes in the Gulf of Mexico area, causing the price of gas to increase and fewer goods to be shipped (13). One hundred and twelve fewer transportation incidents occurred in the 4 months after the hurricane than during that period in the previous year. In addition, 2005 was one of the warmest years since the United States began keeping records and included one of the deadliest tornado outbreaks in recent history, three category 5 hurricanes, and several notable snowstorms (14). The extreme weather conditions in 2005 led to facility shutdowns and transportation route disruptions (15-18).

Natural disasters can cause substantial variations in the HSEES trends for deaths because of small numbers. For example, 18 deaths occurred in the state of Washington from carbon monoxide poisoning when a harsh winter storm caused an electrical outage. During electrical outages, persons often use alternate heating and electrical sources that can cause carbon monoxide poisoning.

The results of this analysis indicate that the economy and weather measurably affect chemical spill and injury trends. Although HSEES states have recorded decreases in the number of incidents and injured persons, the number of deaths has increased. The decreases appear to be in fixed-facility incidents and employee injuries. Because the economy had been declining, discerning whether the decreases are a result of decreases in production, improved safety culture, or both is difficult. An increase in the numbers of injuries and deaths occurred among members of the general public. Many of the general public injuries are from carbon monoxide poisoning, and carbon monoxide poisoning is more common during bad weather because of the increased misuse of home generators and charcoal grills inside the home (19,20). Methamphetamine production incidents also have been increasing and are extremely dangerous to the general public (21). The number of transportation incidents fluctuated and decreased during times of high gas prices and transportation slowdowns.

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least six limitations. First, despite the attempts to make the case definition the same among states, results are not comparable between states because reporting to HSEES was voluntary and data sources varied by state. Second, the results from these nine states might not be representative of the entire United States. Third, inconsistencies within and across states likely exist because reporting capacity (e.g., staffing) or local requirements varied. Specifically, certain states and localities had more stringent reporting regulations than the federal regulations or had more resources to conduct surveillance, possibly resulting in more reported incidents. These factors might have influenced the quality and number of reports or level of detail provided about the incidents. Fourth, changes in reporting guidelines in 2006 (e.g., differences in cleanup requirements) might have affected the trend analyses, particularly because numerous smokestack incidents involving carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, and nitrogen oxides from manufacturing companies were excluded. However, the elimination of these incidents should not have had a substantial effect on the number of injured persons. Fifth, HSEES did not obtain information on all residential incidents. Finally, the category of injured students was intended to include children injured by incidents that occurred at their school. When children are injured at school by incidents that occurred elsewhere (e.g., a factory air release that affected their school), they should be coded as general public; however, in several instances, they were miscoded as students.

Conclusion

Chemical incidents continue to affect public health and appear to be a growing problem for the general public. The number of incidents and injuries varied by month, day of week, and time of day and likely was influenced by other factors such as weather and the economy. The efforts by industries, academia, government agencies, and others to promote safety should continue. New or expanded efforts and outreach to educate consumers who could be exposed to chemicals are needed (e.g., education about the dangers of carbon monoxide poisoning for consumers in areas likely to experience hurricanes). Because outreach by ATSDR and numerous other groups over this 10-year period only slightly decreased incidents and injuries, redirection of efforts such as promoting inherently safer technologies should be explored to reduce or eliminate the hazards completely.

References

- Orum P. Chemical security 101. What you don't have can't leak, or be blown up by terrorists. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress; 2008.

- US Chemical Safety Board. Recommendations. Washington, DC: US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. Available at http://www.csb.gov/recommendations/?F_All=y

.

. - Wattigney WA, Rice N, Cooper DL, Drew JM, Orr MF. State programs to reduce uncontrolled ammonia releases and associated injury using the hazardous substances emergency events surveillance system. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:356-63.

- Belke JC. Recurring causes of recent chemical accidents. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, Plant Maintenance Resource Center; 1998. Available at http://www.plant-maintenance.com/articles/ccps.shtml

.

. - American Chemistry Council. Safety. Washington, DC: American Chemistry Council; 2013. Available at http://www.americanchemistry.com/Safety

.

. - Toxic Use Reduction Institute. Green chemistry. Lowell, MA: University of Massachusetts, Lowell; 2011. Available at http://www.turi.org/Our_Work/Research/Green_Chemistry

.

. - Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance: biennial report 2007-2008. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, CDC. Available at http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HS/HSEES/annual2008.html.

- Orr MF, Sloop S, Wu J. Acute chemical incidents surveillance-Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance, nine states, 1999-2008. In: CDC. Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance, nine states, 1999-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2015;64(No. SS-2).

- Mary Kay O'Connor Process Safety Center. Developing a roadmap for the future of Hazardous Substance Incidents Surveillance. College Station, TX: Mary Kay O'Connor Process Safety Center, Texas A&M University System; 2009. Available at http://pscfiles.tamu.edu/library/center-publications/white-papers-and-position-statements/Developing%20a%20Roadmap%20for%20the%20Future%20of%20National%20Hazardous%20Substances%20Incident%20Surveillance.pdf

.

. - Occupational Safety and Health Administration. U.S. Department of Labor's OSHA issues record-breaking fines to BP. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration; 2009. Available at https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=NEWS_RELEASES&p_id=16674

.

. - US Chemical Safety Board. CSB report on 2008 Bayer CropScience explosion. Washington, DC: US Chemical Safety Board; 2011. Available at http://www.csb.gov/csb-issues-report-on-2008-bayer-cropscience-explosion-finds-multiple-deficiencies-led-to-runaway-chemical-reaction-recommends-state-create-chemical-plant-oversight-regulation

.

. - Saw L, Shumway J, Ruckart P. Surveillance data on pesticide and agricultural chemical releases and associated public health consequences in selected US states, 2003-2007. J Med Toxicol 2011;7:164-71.

- Cable News Network. CNN Money. Experts: $4 a gallon gas coming soon. New York, NY: CNN; 2005. Available at http://money.cnn.com/2005/08/31/news/gas_prices/index.htm

.

. - Shein KA, editor. State of the climate in 2005. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 2006;87:S1-102. Available at http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/bams-state-of-the-climate/2005.php

.

. - Ruckart PZ, Orr MF. 2011. Case studies and lessons learned in chemical emergencies related to hurricanes [Chapter 26]. In Lupo A, ed. Recent hurricane research-climate, dynamics, and societal impacts. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech;2011:483-500.

- Grenzeback LR, Lukmann AT. Case study of the transportation sector's response to and recovery from hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; National Research Council; 2008. Available at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/sr/sr290GrenzenbackLukmann.pdf

.

. - Schnepf R, Chite RM. CRS report for Congress: U.S. agriculture after hurricanes Katrina and Rita: status and issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2005. Available at http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL33075.pdf

.

. - Kumins L, Bamberger R. CRS report for Congress: oil and gas disruption from hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress; 2006. Available at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/rl33124.pdf

.

. - Iqbal S, Clower JH, Hernandez SA, Damon SA, Yip FY. A review of disaster-related carbon monoxide poisoning: surveillance, epidemiology, and opportunities for prevention. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1957-63.

- Lutterloh EC, Iqbal S, Clower J, et al. Carbon monoxide poisoning after an ice storm-Kentucky. 2009. Public Health Rep 2011;126:S(1):108-15.

- Melnikova N, Welles WL, Wilburn RE, Rice N, Wu J, Stanbury M. Hazards of illicit methamphetamine production and efforts at reduction: data from the hazardous substances emergency events surveillance system. Public Health Rep 2011;126(Suppl 1):116-23.

FIGURE 1. Number of chemical incidents, by incident type — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,* 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing numbers of and trends in chemical incidents, by type, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. A total of 57,975 incidents occurred during 1999-2008; 41,993 (72%) occurred in a fixed facility, and 15,981 (28%) were transportation related. Incident type was missing for one incident. The total number of incidents varied, and the trend decreased overall (R2 = 0.3). This decrease was driven by fixed-facility incidents (R2 = 0.6) because of a slight upward trend that occurred in transportation incidents (R2 = 0.3).

FIGURE 2. Number of persons injured in chemical incidents, by incident type — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,* 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in persons injured in chemical incidents, by incident type, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. A total of 15,506 persons were injured; 13,502 were injured in fixed facilities, and 2,004 were injured in transportation-related incidents. The average number of injured persons per year was 1,551. The majority of injured persons were employees (7,674), followed by members of the general public (4,737), students (1,730), and responders (1,340); the population group was unknown for 25 injured persons.

FIGURE 3. Number of persons injured in chemical incidents, by category of injured person* — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,† 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Category missing for 25 injured persons.

† Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in persons injured in chemical incidents, by incident type, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. The trend for number of injured employees decreased slightly but was always higher than the other categories of general public, students, and responders (R2 = 0.3). The number of injured persons from the general public generally increased over time (R2 = 0.3). The number of injured responders decreased slightly (R2 = 0.5). The number of injured students was more variable.

FIGURE 4. Number of deaths from chemical incidents, by incident type — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,* 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in deaths from chemical incidents, by incident type, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. A total of 354 deaths occurred during 1999-2008; 180 deaths were in fixed facilities and 174 were transportation related. The average number of deaths per year was 35. A spike in transportation-related deaths occurred in 2006. The trend for deaths increased (R2 = 0.7), which was driven by incidents in fixed facilities (R2 = 0.5).

FIGURE 5. Number of deaths from chemical incidents, by category of injured person — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,* 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in deaths from chemical incidents, by category of injured person, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. An overall increase in deaths in the general public occurred (R2 = 0.9); no trends were found among employees or responders.

FIGURE 6. Number of incidents and injured persons,* by month — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,† 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Summed over entire period.

† Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Summed over entire period.

† Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text: The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in persons injured by chemical incidents and number of and trends in chemical incidents, by month, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. The number of incidents increased in the spring during March-June, and a decrease occurred in the remainder of the year (R2 = 0.5). The highest number of persons were injured in June (n = 1,683), and the fewest in December (n = 1,034); no trend was found.

FIGURE 7. Number of incidents and injured persons,* by day of the week — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,† 1999–2008

Alternate Text:The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in persons injured by chemical incidents and number of and trends in chemical incidents, by day of the week, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. A decreasing trend in incidents occurred during Monday- Sunday (R2 = 0.7); this trend was similar for the number of injured persons (R2 = 0.6).

FIGURE 8. Number of incidents and injured persons,* by time of day — Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system, nine states,† 1999–2008

Abbreviation: R2 = coefficient of determination.

* Summed over entire period.

† Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Alternate Text:The figure is a line graph showing number of and trends in persons injured by chemical incidents and number of and trends in chemical incidents, by time of day, reported in the nine states (Iowa, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) that participated in the Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance system during 1999-2008. The highest number of incidents occurred earlier in the day (6:00 a.m.-11:59 a.m.) and then decreased as the day went on (R2 = 0.9). Approximately half as many incidents occurred during other times of the day, which was similar for the number of injured persons (R2 = 1.0).

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents.

This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version.

Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr)

and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.

Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371;

telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

**Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to

mmwrq@cdc.gov.