Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Associated Health-Care Resource Use — North Carolina, 2007 and 2009

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including emphysema and chronic bronchitis, is a progressive condition in which airflow becomes limited, making it difficult to breathe. Chronic lower respiratory diseases, primarily COPD, are the third leading cause of death in the United States (1), and 5.1% of U.S. adults report a diagnosis of emphysema or chronic bronchitis (2). Smoking is the primary cause of COPD, and at least 75% of COPD deaths are attributable to smoking in the United States (3). Information on state-specific prevalence of COPD is sparse (4), as are data on the use of COPD-related health-care resources. To understand how COPD affects adults in North Carolina and what resources are used by persons with COPD, 2007 and 2009 data from the North Carolina COPD module of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were analyzed. Among 26,227 respondents, 5.7% reported ever having been told by a health professional that they had COPD. Most adults with COPD reported ever having had a diagnostic breathing test (76.4% in 2007 and 82.4% in 2009). Among adults with COPD, 43.0% reported having gone to a physician and 14.9% visited an emergency department (ED) or were admitted to a hospital (2007) for COPD-related symptoms in the previous 12 months. Only 48.1% of persons reported daily use of medications for their COPD (2007). These results indicate that many adults with COPD might not have had adequate diagnostic spirometry, and many who might benefit from daily medications, such as long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids, are not taking them. Continued and expanded surveillance is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs and support efforts to educate the public and physicians about COPD symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

BRFSS is a state-based, random-digit–dialed telephone survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population aged ≥18 years that is conducted annually by state health departments in collaboration with CDC.* This report summarizes unique state-specific data collected by the North Carolina Division of Public Health in 2007 and 2009. Council of American Survey and Research Organizations (CASRO) response rates† for the state were 55.4% in 2007 and 62.5% in 2009. Cooperation rates§ were 74.8% in 2007 and 80.5% in 2009.

All respondents were asked, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis?" Respondents who answered "yes" to this question were asked a series of follow-up questions about health-care resource use and quality of life related to their COPD.¶ Crude and age-adjusted (5) prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for groups defined by selected characteristics. Statistical significance (p<0.05) was determined by t-test. Follow-up questions were analyzed separately if they were not identical in the 2 years that the COPD module was administered.

Among respondents, 5.7% reported having been told by a health professional that they had COPD, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis (Table). The prevalence of self-reported COPD increased with age, from a low of 3.1% for adults aged 18–44 years, to >10% for adults aged ≥65 years. Respondents with less than a high school diploma were more likely to report COPD (11.1%) than those with a high school diploma (6.7%) or at least some college education (4.2%). No significant differences were observed by sex or race. Current smokers were more likely to report COPD (11.7%) than either former smokers (5.6%) or never smokers (3.0%).

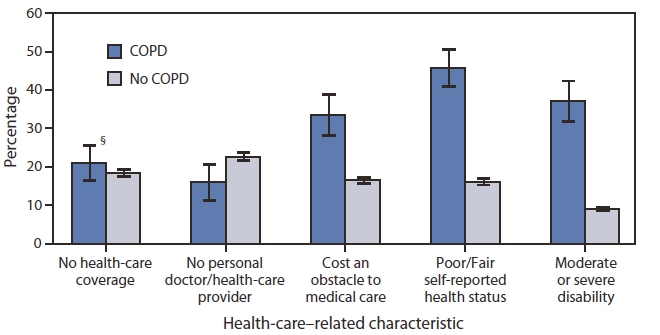

Respondents who reported COPD were less likely to report having no personal doctor or health-care provider (16.0%) than respondents without COPD (23.0%) (Figure). However, persons with COPD were more likely to report cost as an obstacle to medical care (34.0% versus 17.0%), poor or fair health status (46.0% versus 16.0%), or moderate or severe disability (37.0% versus 9.1%), compared with persons without COPD. No statistically significant differences were observed in having health-care coverage based on COPD status.

Among respondents who reported having ever been diagnosed with COPD, 76.4% reported having had a diagnostic breathing test in 2007 and 82.4% in 2009. A doctor's visit for COPD-related symptoms (including shortness of breath, bronchitis, and COPD or emphysema flare) in the past 12 months was reported by 43.0%. More than two thirds of respondents with COPD (70.7%) reported that shortness of breath affected their quality of life. An ED visit or hospital admission for COPD-related symptoms in the past 12 months was reported by 14.9% of respondents with COPD in 2007. In 2009, 13.8% of adults with COPD reported an overnight hospital stay for COPD-related symptoms in the past 12 months. In 2007, 48.1% of respondents with COPD reported use of at least one daily medication for COPD, and in 2009, 28.7% said they had been prescribed prednisone. Adults who reported a physician visit for COPD symptoms, a visit to an ED or hospital admission for COPD, or impaired quality of life because of COPD symptoms were more likely to be using daily COPD medications compared with those without (56.3% versus 28.0%, 71.7% versus 34.8%, and 48.0% versus 25.5%, respectively). Those adults also were more likely to have been prescribed prednisone compared with those without such reports (50.1% versus 11.4%, 69.5% versus 21.7%, and 33.7% versus 13.9%, respectively).

Among respondents who reported a COPD diagnosis, those aged 18–44 years in 2007 were less likely to report having had a breathing test for the diagnosis of their COPD (59.1%; CI = 44.7%–73.4%) compared with all other age groups. In 2009, those aged 18–44 years were less likely to report having had a diagnostic breathing test (70.8%; CI = 58.3%–83.3%) compared with those aged 65–74 years (92.0%; CI = 88.5%–95.4%). No significant differences were observed between groups defined by sex, race, educational level, smoking status, health-care coverage status, having a personal physician or health-care provider, restricted access to doctor because of cost, or self-rated health status. In 2007, those who had visited an ED or had been admitted to the hospital because of COPD were more likely to report a diagnostic breathing test (90.0%; CI = 81.1%–99.0%) compared with those without such a hospital visit (66.8%; CI = 58.3%–75.2%). In 2009, nearly all (99.4%; CI = 98.7%–100.0%) the adults who reported an overnight stay at the hospital for COPD reported a diagnostic breathing test compared with 77.3% (CI = 70.2%–84.3%) of those who did not report an overnight hospital stay. In 2007, 82.9% (CI = 75.6%–90.2%) of adults taking at least one COPD medication daily reported a diagnostic breathing test compared with 61.4% (CI = 51.3%–71.5%) of those not taking any COPD medications.

Reported by

Harry Herrick, MSPH, MSW, MEd, North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics; Roy Pleasants, PharmD, Duke Univ School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina. Anne G. Wheaton, PhD, Yong Liu, MD, Earl S. Ford, MD, Letitia R. Presley-Cantrell, PhD, Janet B. Croft, PhD, Div of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. Corresponding contributor: Anne G. Wheaton, awheaton@cdc.gov, 770-488-5362.

Editorial Note

North Carolina has used the 2007 BRFSS data to identify counties with high COPD prevalence and has implemented public awareness activities for local community and education programs for health-care providers. Most recently, 2007 and 2009 BRFSS data formed the basis for community-based programs that targeted persons with low incomes who used free clinics as their primary source of health care. These programs are taking place through a network of free clinics in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia.

Prevalence of self-reported, physician-diagnosed COPD was 5.7% among adults in North Carolina. More than 20% of respondents with COPD had not been given a breathing test when diagnosed with COPD. Although COPD has no cure, medications are used to improve health status and quality of life by controlling symptoms, reducing the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations, and improving exercise tolerance. A significant proportion of persons who likely suffer from more severe COPD, as suggested by physician visits for COPD symptoms, hospital visits for COPD, and impaired quality of life because of shortness of breath, were not using daily medications to control their COPD. This discrepancy might reflect an underuse of medications to control symptoms. Many respondents also indicated that COPD symptoms resulted in physician and hospital visits in the previous 12 months. These results suggest that COPD is not well-controlled in North Carolina.

The prevalence of COPD in this report is similar to national, self-reported data from 1998–2009 (2). The annual average prevalence of COPD in the U.S. Census division that includes North Carolina (South Atlantic) was 5.8% for 2007–2009 (2). However, if spirometry measures are used as the criterion, data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show that self-reported COPD only identifies half of persons with COPD (6). Therefore, prevalence estimates based on self-report likely are underestimates.

Although most respondents with COPD reported having been given a breathing test to diagnose their COPD, >20% did not report a diagnostic breathing test. Spirometry is important to distinguish between COPD and other conditions, primarily asthma. The specificity that was added to the breathing test question in 2009 (i.e., "...which measures how much air you can breathe out through a tube...") might have aided respondent recall, resulting in a greater number of respondents reporting having had a breathing test compared with 2007 responses. This has implications for future use of this question. Age-adjustment also affected breathing test rates, because young adults are less likely to have the test. This, in turn, argues for the need for younger adults (18–44 years) with COPD symptoms to have a diagnostic breathing test, particularly because COPD is more difficult to diagnosis in its early stages. Conducting spirometry after administration of a bronchodilator also is helpful in predicting how well a patient will respond to treatment. New clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Physicians (7) recommend that "spirometry should be obtained to diagnose airflow obstruction in patients with respiratory symptoms." These respiratory symptoms include chronic cough, wheezing, sputum production, and shortness of breath. Respondents who had visited a hospital for COPD symptoms in the previous 12 months were more likely to have had a diagnostic breathing test. Determining whether this finding was a result of breathing tests being administered to persons with more severe symptoms and possibly more advanced COPD was beyond the scope of the survey.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, BRFSS only surveyed households with landline telephones in 2007 and 2009. The proportion of cellular telephone–only households (no landline, but accessible by cellular telephone) has increased substantially in recent years, which results in a larger segment of the younger, single or never married, Hispanic, or unemployed adult populations not being included in landline samples (8). Because COPD is observed more commonly in older populations, this limitation might not be important. Second, institutionalized persons are not surveyed by BRFSS. Because this category includes older persons in nursing facilities, the actual prevalence of COPD in North Carolina might be higher than it was in the BRFSS sample. Third, the response rates (55.4% in 2007 and 62.5% in 2009) also might limit the generalizability of the results if the characteristics of the respondents and nonrespondents differ. Finally, the BRFSS North Carolina estimates are based on self-report and not on physiologic measures, such as spirometry, and thus might underestimate the actual prevalence of COPD and burden of disease.

Although some data on COPD prevalence on a national or regional level are available, only a few states had undertaken efforts to collect COPD prevalence data before 2011. North Carolina was the first to collect data regarding use of diagnostic breathing tests, physician visits, hospital admissions, and use of COPD medications as part of an existing surveillance system. High quality surveillance data are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs such as the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's "COPD Learn More Breathe Better" campaign** and to improve public and physician awareness of symptoms of COPD, diagnosis, and treatment. In addition to these benefits of expanded surveillance, the public health community can help to reduce the burden of COPD by reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, dust, and other indoor and outdoor air pollutants through tobacco-control and other policies, and by continuing to support and expand smoking cessation programs. Physicians should encourage smoking cessation among all smoking patients. Clinical interventions have been shown to increase motivation to quit and improve abstinence rates (9). Furthermore, smoking cessation decreases the rate in lung function decline among COPD patients (10).

References

- Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Miniño AM, Kung HC. Deaths: preliminary data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2011;59(4). Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_04.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2012.

- Akinbami LJ, Liu X. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS data brief no. 63. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db63.htm. Accessed February 21, 2012.

- CDC. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. MMWR 2008;57:1226–8.

- Brown DW, Pleasants R, Ohar JA, el al. Health-related quality of life and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in North Carolina. North Am J Med Sci 2010;2:60–5.

- Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People Stat Notes. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2012.

- Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance—United States, 1971–2000. Respir Care 2002;47:1184–99.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:179–91.

- Link MW, Battaglia MP, Frankel MR, Osborn L, Mokdad AH. Reaching the U.S. cell phone generation: comparison of cell phone survey results with an ongoing landline telephone survey. Public Opin Q 2007;71:814–39.

- Hopkins DP, Husten CG, Fielding JE, Rosenquist JN, Westphal LL. Evidence reviews and recommendations on interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: a summary of selected guidelines. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(2 Suppl):67–87.

- Lee PN, Fry JS. Systematic review of the evidence relating FEV1 decline to giving up smoking. BMC Med 2010;8:84.

What is already known on this topic?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of death and disability in the United States, but information on state-specific prevalence has been sparse.

What is added by this report?

Among adults in North Carolina, 5.7% reported having been told by a health professional that they had COPD. A majority of persons with COPD had been given a diagnostic breathing test, but less than half were using daily COPD medications.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Physicians should conduct spirometry to diagnose COPD and prescribe appropriate medications to control symptoms and reduce exacerbations. Clinicians and the public health community also should support smoking cessation efforts.

|

Characteristic

|

No. of respondents†

|

No. with COPD†

|

%

|

(95% CI)

|

|

Total*

|

26,227

|

2,187

|

5.7

|

(5.3–6.1)

|

|

Year*

|

|

2007

|

13,990

|

1,195

|

6.0

|

(5.5–6.6)

|

|

2009

|

12,237

|

992

|

5.4

|

(4.8–6.0)

|

|

Age group (yrs)

|

|

18–44

|

7,395

|

256

|

3.1

|

(2.5–3.7)

|

|

45–54

|

5,202

|

361

|

6.4

|

(5.3–7.6)

|

|

55–64

|

5,587

|

570

|

8.6

|

(7.7–9.5)

|

|

65–74

|

4,579

|

608

|

11.7

|

(10.6–12.9)

|

|

≥75

|

3,464

|

392

|

10.4

|

(9.1–11.7)

|

|

Sex*

|

|

Men

|

9,622

|

693

|

5.3

|

(4.7–6.1)

|

|

Women

|

16,605

|

1,494

|

6.0

|

(5.5–6.5)

|

|

Race*

|

|

White

|

20,823

|

1,830

|

5.7

|

(5.2–6.1)

|

|

Black

|

3,668

|

244

|

4.9

|

(3.7–6.1)

|

|

Other§

|

1,606

|

106

|

6.7

|

(5.0–8.5)

|

|

Educational level*

|

|

Less than high school diploma or GED

|

3,521

|

547

|

11.1

|

(9.4–12.8)

|

|

High school diploma or GED

|

7,766

|

766

|

6.7

|

(5.7–7.6)

|

|

At least some college

|

14,914

|

873

|

4.2

|

(3.7–4.6)

|

|

Smoking status*

|

|

Current smoker

|

5,015

|

791

|

11.7

|

(10.4–13.1)

|

|

Former smoker

|

7,948

|

877

|

5.6

|

(4.9–6.3)

|

|

Never smoked

|

13,175

|

513

|

3.0

|

(2.5–3.5)

|

FIGURE. Age-adjusted* percentage of selected health-care–related characteristics† by COPD status — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, North Carolina, 2007 and 2009

Alternate Text: The figure above shows the age-adjusted percentages of selected health-care-related characteristics by chronic obstructive pulmonary (COPD) status of persons in North Carolina during 2007 and 2009, according to data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Respondents who reported COPD were less likely to report having no personal doctor or health-care provider (16.0%) than respondents without COPD (23.0%). However, persons with COPD were more likely to report cost as an obstacle to medical care (34.0% versus 17.0%), poor or fair health status (46.0% versus 16.0%), or moderate or severe disability (37.0% versus 9.1%), compared with persons without COPD. No statistically significant differences were observed in having health-care coverage based on COPD status.