Key points

- Each year, 1.4 million Americans receive healthcare for a possible rabies exposure, 100,000 receive post-exposure prophylaxis, and fewer than 10 die from rabies due to robust prevention efforts.

- CDC houses the only U.S. reference laboratory for diagnosing rabies and provides support to U.S. laboratories, health departments, and hospitals.

- CDC's National Rabies Surveillance System tracks cases to monitor changes in the spread of rabies.

- Raccoons, skunks, and foxes continue to pose significant rabies threats to 75% of Americans.

Public health importance of rabies

Rabies is a rare but serious public health concern in the United States. Before 1960, several hundred people died of rabies each year. Thanks to the coordinated efforts of human and animal health experts, fewer than 10 human deaths are reported each year in the U.S. While rabies is uncommon in humans, three out of four Americans live in a community where raccoons, skunks, or foxes carry this deadly disease.

In the U.S., around 4,000 animal rabies cases are reported each year, with more than 90% occurring in wildlife like bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes. This is a big change from the 1960s, when domestic animals, mainly dogs, represented most of the rabies cases.

The decrease in human deaths from rabies is directly related to:

- Successful vaccination of pets and animal control programs

- Public health tracking and testing of human and animal rabies cases

- The availability and use of rabies-related medical care, called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Even though rabies is well-controlled in the U.S., more than 6 million Americans report animal bites each year, 1.6 million seek medical attention, and around 100,000 get PEP. Rabies vaccines are complex, expensive, and limited. Public health programs can assess each person who may have been exposed to rabies to determine if they need rabies-related medical care, including the vaccine.

Sometimes, people still die from rabies, usually because they didn't get medical help soon enough after being scratched or bitten. It's important to be aware of the risk, especially with bat bites, which can be easy to ignore because they don't always leave obvious marks.

Animal rabies surveillance in the U.S.

Every year, the CDC collects and analyzes data on rabies cases in animals and people from state health departments. The latest report, Rabies Surveillance in the United States, gives a detailed look at the current rabies landscape in the United States:

- Wildlife rabies surveillance: Wild animals account for more than 90% of reported cases, with bats (35%), raccoons (29%), skunks (17%), and foxes (8%) most often exposing Americans to rabies.

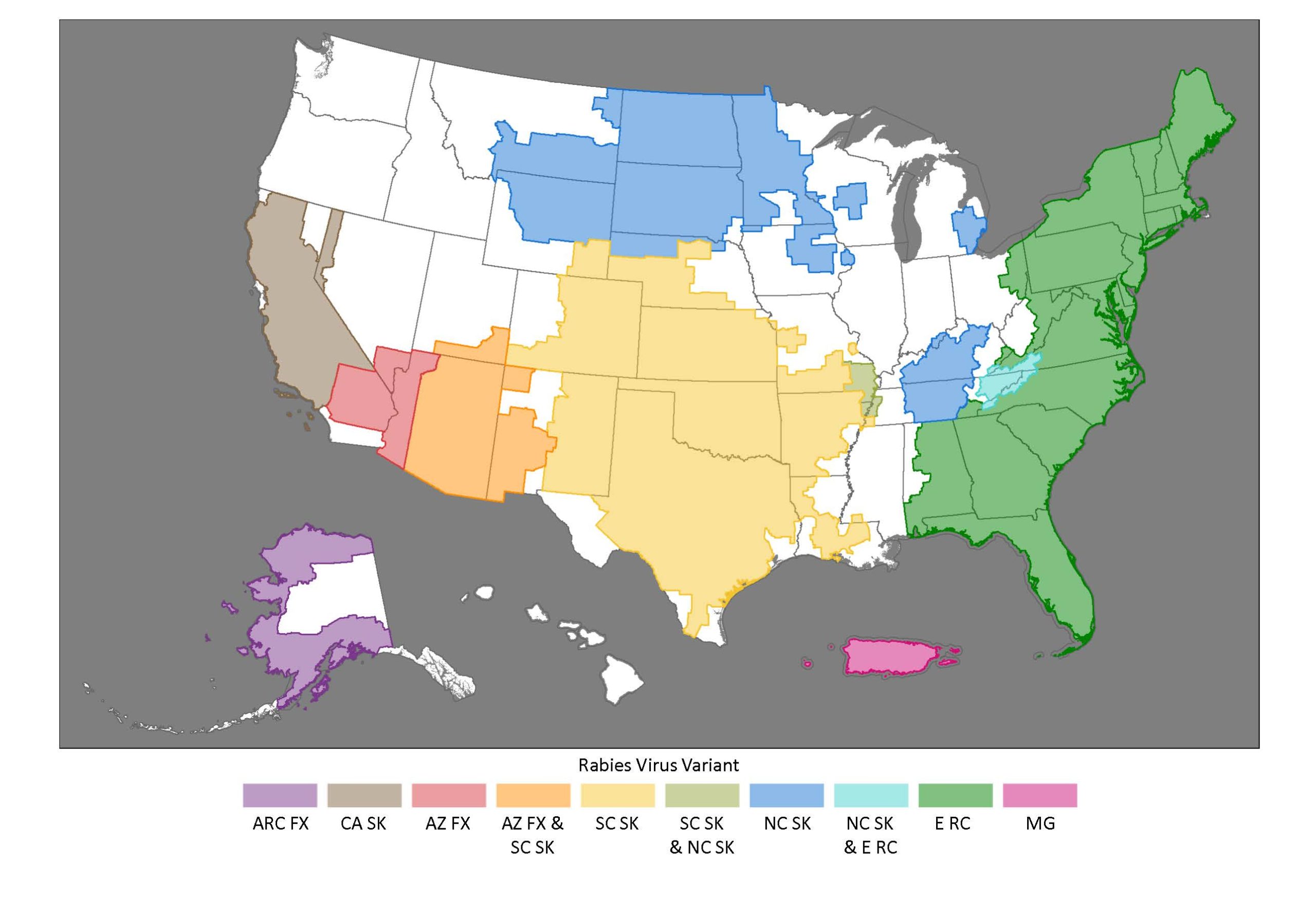

- Rabies virus variants: The rabies virus has adapted to specific animal reservoir hosts (like raccoons, bats, skunks, and foxes), and these variants can be found in specific parts of the U.S.

Confirmed animal rabies cases in the United States

Rabies animal reservoirs in the U.S.

Bats: Rabid bats are found in all U.S. states, except for Hawaii. While certain bats are more commonly diagnosed with rabies, all bat species are susceptible and any direct contact with a bat should be reported to a medical provider or your public health department.

Raccoons: Raccoons are a rabies reservoir in the eastern United States, extending from Canada to Florida and as far west as the Appalachian Mountain range. Within these areas, 10% of raccoons that expose people or pets have rabies, making them one of the highest rabies-risks in the United States. However, rabid raccoons are rarely reported outside of the eastern U.S., highlighting the importance of considering the local patterns of rabies when assessing a patient's rabies exposure risk.

Skunks: Skunks are a rabies reservoir across most states in the Midwest and Western parts of the United States. While exposures to rabid skunks are uncommon, when they do occur, more than 20% of skunks that expose people or pets have rabies. This means that skunks are the highest risk for rabies in the U.S., if they bite or scratch a person or pet. Even skunks found in states where raccoons are the reservoir are considered high-risk.

Foxes: Foxes are a reservoir for rabies in the Southwestern United States (Gray Foxes) and Alaska (Arctic Foxes). Like skunks, more than 20% of foxes that bite or scratch people or pets have rabies. While the risk is highest in the U.S. Southwest and Alaska, rabid foxes have been reported in many parts of the country and should be considered a high-risk exposure. Since 2023, rabies outbreaks in foxes have been reported in Arizona, California, and Alaska.

Mongoose: Mongoose are a rabies reservoir in Puerto Rico, and they often infect unvaccinated, stray dogs. More than 80% of mongooses that expose people or pets have rabies, making them the highest risk rabies exposure on the island. In Puerto Rico, dogs are also often reported with rabies, and exposure to unfamiliar or strange-acting dogs should always be regarded as high-risk.

Other mammals do get rabies in the U.S., despite not being reservoirs for this disease. Any contact with unfamiliar and strange acting animals should be reported to health authorities, who can determine if you need further medical care.

Rabies Virus Variant territories in the United States. Abbreviations: ARC FX = Arctic Fox, CA SK = California Skunk, AZ FX = Arizona Gray Fox, SC SK = South Central Skunk, NC SK = North Central Skunk, E RC = Eastern Raccoon, MG = Mongoose

Prevention efforts

Human rabies cases in the United States are rare because of comprehensive efforts across sectors:

- Wildlife vaccination: Wildlife professionals distribute more than 10 million oral vaccines to wild animals annually through baits.

- Pet vaccination: Veterinary professionals vaccinate more than 91million cats and dogs each year, keeping pets and families safe.

- Animal re-homing: Humane societies and shelters find new homes for stray animals, lowering the risk of rabies being contracted or spread.

- Research and development: Scientists continuously work to improve vaccines and find new treatments for rabies.

Wildlife rabies management

The United States National Wildlife Rabies Management Program is a collaboration of more than 50 U.S. animal and human health organizations to implement a coordinated, cost-effective, evidence-based program to control rabies in wildlife. Under this plan, each year more than 7 million wildlife vaccine baits are distributed to prevent rabies spread. CDC's National Rabies Reference Laboratory provides diagnostic testing expertise to help maintain accurate testing at more than 130 U.S. laboratories. CDC's National Rabies Surveillance System works with 54 public health jurisdictions to analyze rabies patterns.

Response measures

Veterinary professionals, animal control officers, and public health workers play an important role in responding to a potential rabies exposure by determining the risk of rabies. Specifically, they conduct:

- Assessments: Veterinary evaluations and public health interviews help determine exposure risk.

- Testing: More than 130 labs test nearly 100,000 animals for rabies annually. In a typical year, more than 3,500 animals test positive for rabies.

Human rabies surveillance in the U.S.

From 2015 to 2024, 17 cases of human rabies were documented, 2 of which were contracted outside of the United States.

Even though human rabies cases are rare, each year hundreds of thousands of animals are observed or tested for rabies, and 100,000 people require PEP. Ongoing potential for animal exposure and the deadly nature of rabies drive home the need to track disease patterns and continue programs to help avoid exposures to rabies.

Rabies-related Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) features rabies case reports, investigations, analyses, treatment recommendations, and more.

- Human Rabies Deaths — Minnesota and California, 2024

- Imported Human Rabies — Kentucky and Ohio, 2024

- Rabies Cluster Among Steers on a Dairy Farm — Minnesota, 2024

- Human-to-Human Rabies Transmission via Solid Organ Transplantation from a Donor with Undiagnosed Rabies — United States, October 2024–February 2025

- Rabies Outbreak in an Urban, Unmanaged Cat Colony — Maryland, August 2024

- Notes from the Field: Enhanced Surveillance for Raccoon Rabies Virus Variant and Vaccination of Wildlife for Management — Omaha, Nebraska, October 2023–July 2024

- Notes from the Field: Heightened Precautions for Imported Dogs Vaccinated with Potentially Ineffective Rabies Vaccine — United States, August 2021−April 2024

- Human Rabies — Texas, 2021

- Rabies in a Dog Imported from Azerbaijan — Pennsylvania, 2021

- Use of a Modified Preexposure Prophylaxis Vaccination Schedule to Prevent Human Rabies: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022

- Translocation of an Anteater (Tamandua tetradactyla) Infected with Rabies from Virginia to Tennessee Resulting in Multiple Human Exposures, 2021

- Notes from the Field: Three Human Rabies Deaths Attributed to Bat Exposures — United States, August 2021

- Rabies in a Dog Imported from Egypt — Kansas, 2019

- Evaluation of Online Risk Assessment To Identify Rabies Exposures Among Health Care Workers — Utah, 2019

- Human Rabies — Utah, 2018

- Notes from the Field: Rabies Exposures from Fox Bites and Challenges to Completing Postexposure Prophylaxis After Hurricane Irma — Palm Beach County, Florida, August–September 2017

- Notes from the Field: A Multipartner Response to Prevent a Binational Rabies Outbreak — Anse-à-Pitre, Haiti, 2019

- Notes from the Field: Rabies Outbreak Investigation — Pedernales, Dominican Republic, 2019

- Vital Signs: Trends in Human Rabies Deaths and Exposures — United States, 1938–2018

- Human Rabies — Virginia, 2017

- Rabies in a Dog Imported from Egypt — Connecticut, 2017

- Translocation of a Stray Cat Infected with Rabies from North Carolina to a Terrestrial Rabies-Free County in Ohio, 2017

- Notes from the Field: Identification of Tourists from Switzerland Exposed to Rabies Virus While Visiting the United States — January 2018

- Notes from the Field: Assessing Rabies Risk After a Mass Bat Exposure at a Research Facility in a National Park — Wyoming, 2017

- Notes from the Field: Assessment of Rabies Exposure Risk Among Residents of a University Sorority House — Indiana, February 2017

- Potential Confounding of Diagnosis of Rabies in Patients with Recent Receipt of Intravenous Immune Globulin

- Notes from the Field: Postexposure Prophylaxis for Rabies After Consumption of a Prepackaged Salad Containing a Bat Carcass — Florida, 2017

- Announcement: Release of National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians' 2016 Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control

- Human Rabies — Puerto Rico, 2015

- Human Rabies — Wyoming and Utah, 2015

- Assessment of Health Facilities for Control of Canine Rabies — Gondar City, Amhara Region, Ethiopia, 2015

- Human Rabies — Missouri, 2014