Logger Killed When Stuck by Rebounding Tree

FACE 99AK021

Release Date: July 13, 2000

SUMMARY

A logger (the victim) was killed while cutting a tree that rebounded after it became lodged in the fork of two trees. The victim was one of three cutters assigned to a work site on a steep forested hillside. There were no witnesses to the incident, but the evidence indicated that the victim was felling trees as he ascended the slope. His intended lay for the tree was across the slope of the hillside. The tree fell slightly uphill and became lodged in the fork of two trees. As the weight of the cut tree was held by the fork, the top of the cut tree broke off. The release of counterweight caused the lower portion of the tree to rebound up the slope and to strike the cutter.

After the victim’s coworkers met at an agreed upon meeting spot, they hiked back to his last sighted location. The victim was found next to his chainsaw, without pulse or respiration. The victim’s coworkers hiked back to their truck and reported the incident by radio. Alaska State Troopers were notified and the body was recovered. The victim was pronounced dead at the scene.

Based on the findings of this investigation, to prevent similar occurrences, employers should:

- Ensure that all cutters are capable of casing trees for internal rot so that they can modify their cutting procedures, if necessary;

- Ensure that all cutters working on steep terrain fell trees according to safe methods in accordance with 29 CFR 1919.266.

INTRODUCTION

At approximately 1:30 P.M. on July 19, 1999, a 50-year-old male timber cutter (the victim) was fatally struck by the butt of a tree he was felling. On July 20, 1999, Alaska Department of Labor (AKDOL) notified the Alaska Division of Public Health, Section of Epidemiology. An investigation involving an injury prevention specialist for the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Section of Epidemiology, ensued on July 21, 1999. The incident was reviewed with AKDOL and the Alaska State Trooper investigators. AKDOL, Alaska State Trooper, and Alaska Medical Examiner reports were requested. An inspection of the site was completed on July 23, 1999.

The company in this incident was a privately owned logging operation that had been timber harvesting for 28 years. The company had more than 700 employees nationwide, of which 100 were employed in Alaska. Thirty to 35 employees, including 10 timber cutters, resided at the work site location. The victim was an experienced cutter and had been employed by the company since 1997 and had worked at various sites around the United States.

The company had a written safety and health plan that specifically addressed timber cutting and timber harvesting issues. At the time of hire, employees received safety and health training. The company trainer used a checklist and placed it in the employee’s permanent personnel-training file. All employees were required to attend an initial hire orientation and to receive CPR and first aid training, if necessary, for current certification. In addition, employees were assessed for individual skills and knowledge by a cutting supervisor. Intermittent observations were made while working in their assigned areas to provide recommendations and corrective actions. If necessary, employees were reassigned if they could not safely perform their assigned tasks.

INVESTIGATION

The incident occurred on a steep remote hillside in southeast Alaska, approximately 15 miles (14 logging road miles plus 1 mile by foot) from the main camp. Cutters traveled to their assigned site first by truck and then foot. Each cutter was required to carry a small emergency first aid packet, personal protection equipment, and cutting equipment. Cutters normally worked in pairs (double jacking) or in teams of three. They were assigned individual stands but were required to stay within voice and visual contact. Individual cutters did not carry two-way radios, however each transport vehicle was equipped with a radio.

The primary type of harvesting undertaken by the logging operation was clear-cut. The terrain of the harvest area varied in slope, altitude, and ground conditions. The incident site was located on a 30-40 degree slope, less than 1000 feet in elevation. Ground conditions consisted of light to moderate brush and slash with occasional areas of heavier brush. Forest composition consisted of conifers. The timber stands were naturally occurring and were marked for cutting. Weather at the time of the incident was rain with variable winds. Visibility was not affected. Weather was not considered a factor in this incident.

Upon completion of a site survey, the cutting supervisor assigned stands of timber to the individual cutters. The three marked stands assigned to the team were adjacent to each other on the slope at the end of a ridge. The first and third stands were on opposing sides of the ridge. Due to the arrangements of the stands, the cutters could not maintain continuous visual contact with each other. They could hear each other working and yell back and forth. The last voice contact with the victim was at approximately 1:30 P.M. The victim and one cutting partner were shouting their current positions and indicated that there were no problems. During the dialogue, the victim had communicated some concern to his partner that he had not heard that partner run his chainsaw for a period of time. He wanted to make sure the partner was not near any of the trees the victim was intending to fell.

Since the incident was not witnessed, it was surmised from the evidence that the victim had intended to fell a tree across the slope below the remaining trees. Some brush, but not all, had been cut in the direction opposite the intended lay (the intended direction of the falling tree), possibly for an escape route. The height of the tree was approximately 140 feet. The stump diameter of the felled tree was approximately 48 inches by 36 inches. The upslope side of the stump was folded, having a pleated appearance. The top of the stump showed a significant area of rot in a triangular shape, measuring 24 inches by 16 inches (Figure 1). The rot was more extensive in the area of the holding wood near the folded trunk surface. The victim had made two cuts to fell the tree, a Humboldt undercut followed by a back cut (Figure 2). A larger than normal width of holding wood was left on the stump. The tree appeared to have pulled away prematurely and fell uphill from the intended lay. A fork created by a 140-foot tree and a 50-foot windfall stump were upslope of the intended lay, approximately 50 feet from the stump (Figure 3). The falling tree lodged in the fork (Figure 4), causing the top 40 feet of the felled tree to break off. The remaining log pivoted in the fork, and the butt rebound upslope. The butt of the log struck the victim’s upper back.

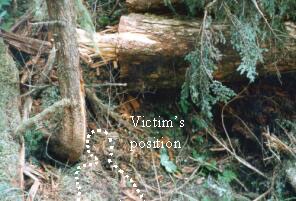

At 2:00 P.M., the agreed upon time to quit work, the victim’s partners walked to their agreed upon meeting spot. The victim did not return, and an idling chainsaw could be heard. Company policy dictated that cutters turn off their chainsaws when not in use. The sound of an idling chainsaw meant there might be a problem. The victim’s partners walked back to the victim’s last known location and found him 13 feet up slope from the stump. His cutting equipment was near by. He was lying facing into the slope in a slightly bent over position. The butt end of a log was directly uphill from the victim (Figure 5). Smudge marks were apparent on the victim’s back, indicating that the tree butt had struck the victim as it swung. It could not be determined if the victim was moving toward his escape route at the time of the incident. The victim’s cutting partners hiked back to the truck on the logging road and radioed the camp. Alaska State Troopers were notified. The victim was pronounced dead at the scene, and the company was given permission to recover the body.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The death certificate listed the cause of death as impact injuries due to being struck by a falling tree.

|

|

|

Figure 1. View of holding wood |

Figure 2. View of holding wood |

|

|

|||

|

Figure 3. View of trees upslope of intended lay |

Figure 5. Victim’s position below log |

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Employers should ensure that all cutters are capable of casing trees for internal rot so that they can modify their cutting procedures, if necessary.

Discussion: Examination of the scene indicated that the victim had some safe felling techniques—

- The intended lay was across the slope, providing an area where the log could be safely bucked (or limbed and sawed into sections);

- A possible escape route was cleared of some, but not all, brush; and

- A clean, uniform undercut and level backcut were completed.

However, the undercut penetrated an area of heart rot. Heart rot is more common is older trees and is usually caused by damage or injury to the trunk at an earlier stage of growth. The core can continue to degrade while the external wood heals around the original injury. This seriously compromises the holding wood that acts as a hinge to help control the tree’s fall. Examination of the wedge or shavings from the undercut may have shown signs of discoloration or rot and indicated the wood within the core was substantially weaker than the peripheral wood of the trunk.

Recommendation #2: Employers should ensure that all cutters working fell trees according to safe methods in accordance with 29 CFR 1919.266(d)(6).

Discussion: In this incident, the team members were working individually in adjacent stands. However, the stands were located 1 mile from the logging road and went around the tip of a ridge, which caused the cutting team to lose visual and potentially audible contact with each other. 29 CFR 1919.266(d)(6) requires that at least two tree lengths separate a felling area from an adjacent work area and that cutters maintain visual or audible contact with other workers. At many logging sites in Alaska, the terrain including slope, altitude, and the lay of the land (rigs, gullies, outcroppings, etc.) of assigned timber stands result in greater distances between timber workers and brief interruptions in contact between cutters during the workday. Employers should consider providing all cutters with two-way radios to maintain contact when terrain may potentially prevent visual and audible contact. In addition to the CFR, the State of Alaska, Occupational Safety and Health Standards adopted state-based logging standards. For medical and first aid purposes, 8 AAC 61.1060(c)(1) requires employers to provide radio communication within ½ mile of working timber crews.

REFERENCES

Alaska Department of Labor, Division of Labor Standards and Safety: Occupational Safety and Health Standards, Additional Logging Standards, 8 Alaska Administrative Code 61.1060. Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Department of Labor, 1995.

Conway S. Logging practices: principles of timber harvesting systems. Rev. ed. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Publications, 1982.

Fallers’ and Buckers’ handbook, 9th Ed. Vancouver, Canada: Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 1990.

Logging from felling to first haul. Criteria document for a recommended standard. US Dept of Health, Education and Welfare publication no. (NIOSH) 76-188, 1976.

Logging safe practices guide, Alaska Timber Insurance Exchange.

Office of the Federal Register: Code of Federal Regulations, Labor 29 Part 1910. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996.

Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) Project

The Alaska Division of Public Health, Section of Epidemiology performs Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation (FACE) investigations through a cooperative agreement with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Division of Safety Research (DSR). The goal of these evaluations is to prevent fatal work injuries in the future by studying the working environment, the worker, the task the worker was performing, the tools the worker was using, the energy exchange resulting in fatal injury, and the role of management in controlling how these factors interact.

To contact Alaska State FACE program personnel regarding State-based FACE reports, please use information listed on the Contact Sheet on the NIOSH FACE web site Please contact In-house FACE program personnel regarding In-house FACE reports and to gain assistance when State-FACE program personnel cannot be reached.