Hispanic Painter Electrocuted When The Ladder He Was Carrying Contacted a 13,200 Volt Overhead Powerline - North Carolina

NIOSH In-house FACE Report 2003-08

February 27, 2004

Summary

On February 24, 2003, a 32-year-old Hispanic painter (the victim) was electrocuted when the metal ladder he was carrying contacted an overhead powerline. Prior to the incident, the victim and his co-workers had been painting a private residence. As the workers were beginning to clean up the job site at the end of the work day, the victim picked up a metal ladder to carry it to the work van. While the victim was carrying the ladder upright to the van, the foreman and several co-workers verbally warned him about the overhead powerline. Several seconds later, the victim’s ladder made contact with the overhead powerline and the victim fell to the ground. The foreman and co-workers ran to assist the victim. After a co-worker made several unsuccessful attempts to call for assistance, the foreman went to a nearby home to call 911. When the foreman returned, he performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on the victim who had no pulse and was not breathing. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and police personnel responded to the scene. The victim was transported via ambulance to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead in the emergency room.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to help prevent similar occurrences, employers should

- eliminate the use of conductive ladders in proximity to energized overhead powerlines

- conduct a jobsite survey to identify potential hazards and develop and implement appropriate control measures for these hazards

- develop, implement and enforce a comprehensive safety program and training in language(s) and literacy level(s) of workers which includes training in hazard recognition and the avoidance of unsafe conditions.

- ensure that employees are provided with a means for emergency communication and are also trained in first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when worksites are in remote locations

Additionally, ladder manufacturers should

- consider affixing dual language labels with graphics to provide hazard warnings and instructions for safe use of equipment

Introduction

On February 24, 2003, a 32-year-old Hispanic painter (the victim) was electrocuted when the metal ladder he was carrying contacted an overhead powerline. On April 1, 2003, officials of the North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Administration (NCOSHA) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Division of Safety Research (DSR), of the incident. On April 15, 2003, two DSR safety and occupational heath specialists met with the NCOSHA safety compliance officer who had investigated the incident to discuss the case and to review information collected and photographs taken during the course of the NCOSHA investigation. A review of the county police report was also conducted. The DSR investigators visited the site, interviewed the employer and workers, and took photographs. The official cause of death was obtained from the death certificate.

Employer. The victim’s employer was a painting contractor. The business had been owned by a father and his son. The son became the present owner of the business in 1990. The company employed 10 full-time workers; 7 of the workers were of Hispanic origin. The foreman on the job site had been in his position for approximately 10 months, and was a family member to the company owner. The company had the foreman and a crew of four painters working on this jobsite at the time of the incident. The employer and crew had been working at the site sporadically for 1 month, coordinating with other jobs. The employer visited the incident site regularly to assess progress. Three of the four painters on the job were Hispanic. The crew foreman spoke only English. The police interviewed the foreman and the crew following the incident, and provided written statements to NCOSHA. The police used an interpreter to obtain and translate statements from two of the Hispanic crew members. This was the company’s first workplace fatality.

Victim. The 32-year-old male victim had moved from Mexico to the United States approximately 18 years prior to the incident, and he had been working for the company as a painter for 2 years. The victim’s primary language was Spanish; however he also reportedly spoke English. While working together on the job site, the Hispanic workers spoke only Spanish to each other. However, when the employer and the foreman addressed all the workers, English was the language used. During DSR witness interviews, only one of the Hispanic co-workers was available. The interview with the Hispanic co-worker proved to be difficult, due to the limited use of the English language and a lot of communication through hand and body gestures.

Training. The company had no written comprehensive safety program. On-the-job training was provided on an as-needed basis by the foreman or the owner to warn the workers of potential worksite hazards. This training was not documented by the company. The victim had no training beyond on-the-job task training.

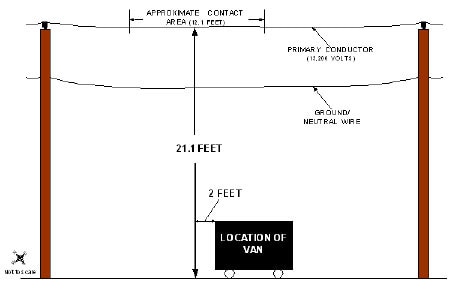

Incident Scene. The employer was contracted to re-paint a 100-year-old, 2-story wood-frame house (approximately 2,000 square feet) that had been moved from its original location to the cleared property where the incident occurred (Photo 1). The house was occupied, however the homeowner was not present when the incident occurred. An energized 13,200-volt overhead powerline was located approximately 26 feet in distance from the front of the house. The primary conductor (top line) was approximately 21 feet above the ground level and the neutral/ground wire (bottom line) was approximately 17 feet above the ground (Diagram).

|

|

Diagram. The overhead powerlines layout at the incident scene

|

Ladder. The victim was using a 40-foot aluminum, two-section, Type I-Heavy Duty/Commercial use ladder at the time of the incident. The ladder sections had been retracted to approximately 20-feet when the ladder made contact with the powerline.

Weather. It was daylight at the time of the incident, with sunny and clear conditions, and the temperature was in the 60’s.

Back to Top

Investigation

Prior to beginning the job, the home owner reportedly verbally warned the painting contractor and the workers of the nearby overhead powerline. The foreman and crew arrived on site at approximately 8:00 a.m. on the day of the incident and parked a work van under the overhead powerlines in front of the house (Photo1). The workers unloaded equipment and ladders from racks on top of the van. The foreman and the crew placed ladders and equipment at various locations around the house and began painting.

At approximately 12:00 p.m., the foreman and workers stopped painting for lunch. The van was moved to a driveway area, which was located approximately 30 feet from the front of the house, because the owner of the company was due to arrive at the site with some additional painting materials. Following lunch, the owner left the site and the foreman and crew resumed painting. Towards the end of the work day, the victim began cleaning up the job site. Knowing that the ladders and equipment needed to be loaded back into the van, a co-worker moved the van back to the front of the house under the 13,200-volt overhead powerline (Diagram). At approximately 3:50 p.m., the foreman was in the process of picking up his aluminum ladder which had been shortened to approximately 20 feet in length to carry it to the van. As he attempted to move his ladder, the foreman stumbled and the victim, standing nearby, grabbed the ladder. The victim told the foreman that he had the ladder and he proceeded to carry the ladder in an upright vertical position approximately 15 feet toward the van. As he approached within approximately three feet from the rear of the van, the foreman and a co-worker both shouted to the victim to watch for the overhead powerline. Moments later, the ladder made contact with the overhead powerline.

The foreman and two workers standing in front of the house observed the ladder touch the powerlines and the victim gripping the ladder while in a “frozen” position. Seconds later, the neutral/ground wire(bottom line) burned through and fell, and the victim lost grip of the ladder and fell to the ground. The foreman and co-workers ran over to the victim lying on the ground with his left pant leg and shoe on fire. After the foreman patted the fire out with his hands, he checked the victim for vital signs, and found that he had a slight pulse and labored breathing. The foreman told a co-worker to go to a neighboring house to call 911. Several minutes later, the foreman observed the worker running back towards him and yelling that he was unable to call for help, because there was no one home. The foreman ran to another home where he called 911 requesting medical assistance at 4:07 p.m. After calling for help, the foreman ran back to the victim, found him not breathing, and began cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

At approximately 4:16 p.m., Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and police arrived on the scene. EMS assessed the victim and found that he had an entrance wound on his right hand and an exit wound on his left foot. After not being able to locate any vital signs, they administered an external defibrillator several times. The victim was transported via ambulance to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead in the emergency room.

Back to Top

Cause of Death

The medical examiner’s report indicated that the cause of death was high voltage electrocution.

Back to Top

Recommendations/Discussion

Recommendation #1: Eliminate the use of conductive ladders in proximity to energized overhead powerlines.1,2

Discussion: Energized overhead powerlines in proximity to a work area constitute a safety hazard. Extra caution must be exercised when working near energized powerlines. A safe distance between powerlines and ladders, tools, and work materials should be maintained at all times. Metal ladders should not be used for electrical work or where they may contact electrical conductors. Ladders made of non-conductive materials, e.g., fiberglass, should be substituted for work near energized electrical conductors. The powerlines in this incident were approximately 26 feet from the front of the structure.

Recommendation #2. Conduct a jobsite survey to identify potential hazards and develop and implement appropriate control measures for these hazards. 3

Discussion: Before beginning work at any site, a competent persona should evaluate the site to identify any potential hazards and ensure appropriate control measures are implemented. The jobsite had identifiable hazards (i.e., a 13,200-volt overhead powerline close to the structure where the work was being performed and the work van).

In this incident, appropriate control measures may have included using non-conductive ladders at the site and designating a safe area at the work site where the work van would be positioned for loading, unloading and parking. Equipment, material, and supplies should be loaded, transported, and unloaded in a manner which does not create a hazard at the jobsite. An area should be designated and marked (perhaps with barricades) at the worksite to provide the safest route for the required job duties.

Recommendation #3: Develop, implement and enforce a comprehensive safety program and training in language(s) and literacy level(s) for all workers which includes training in hazard recognition and the avoidance of unsafe conditions. 4

Discussion: The comprehensive training plan should identify required safety training, ( i.e., working around electricity and overhead powerlines, and ladder safety). Overcoming language and literacy barriers is crucial to providing a safe work environment for a multilingual workforce. Companies that employ workers who do not understand English should identify the languages spoken by their employees, and design, implement, and enforce a multilingual safety program. The safety program and training should be developed at a literacy level that corresponds with the literacy level appropriate for the company’s workforce.

Employers should ensure that employees who do not speak English or have limited use of English are afforded an interpreter who can clearly convey instructions, and ensure that employees clearly understand the instructions given. The program, in addition to being multilingual, should include a competent interpreter to explain worker rights to protection in the workplace, safe work practices workers are expected to adhere to, specific safety protection for all tasks performed, ways to identify and avoid hazards, and whom they should contact when safety and health issues arise. A method to ensure comprehension of information could be to provide testing to ensure that the information conveyed was understood.

Recommendation #4. Ensure that employees are provided with a means for emergency communication and are also trained in first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when worksites are in remote locations.5

Discussion: In this incident, the employees did not have a means of emergency communication on the worksite. An estimated 15 minutes was spent by the foreman and the crew attempting to locate a nearby telephone to call for emergency assistance. Employers should contact a cellular phone or 2-way radio company for methods to ensure communication to either the company’s designee, or to emergency response personnel. If a company relies on cellular telephones as a means for communications, the phone should be tested at each work site to determine if a signal can be obtained, before the telephone is relied upon for emergency communication.

When an injury-producing incident occurs at a worksite, timely emergency care provided to the victim may reduce the consequences of the injury. Although first aid and/or CPR may not have affected the outcome of this case, such training could help save lives in similar future events.

Additionally, ladder manufacturers should

Consider affixing dual language labels with graphics to provide hazard warnings and instructions for safe use of equipment.6-9

Discussion: Over the past several years, the United States has seen a dramatic increase in its population of Hispanic, Spanish-speaking citizens who are entering the work force. According to the United States Bureau of the Census, in 1996, Hispanics comprised 10.5 percent of the total population in the U.S. By 2005, their population share is projected to be 12.6 percent. According to The Center To Protect Workers’ Rights, in 2000, about 14.7 million Hispanics were employed in the U.S., making up 10.9% of the U.S. workforce.

Having employees who speak limited or no English presents unique challenges. It is important for Spanish-speaking employees to be able to interpret instruction and warning labels on work equipment, such as ladders. While some equipment is bought or shipped with manufacturers’ documentation in at least one other language other than English, many instruction and warning labels are only in English (Photo 2). A dual language label with a graphic or picture label could offer an additional warning to workers of potential hazards.

a Competent person is defined by OSHA as one who is capable of identifying existing and predictable hazards in the surroundings or working conditions which are unsanitary, hazardous, or dangerous to employees, and who has the authorization to take prompt corrective measures to eliminate them.

|

|

Photo 2. Hazard warning on the ladder used in this incident

|

Back to Top

References

- NIOSH [2002]. Electrical Safety, Safety and Health Electrical Trades Student Manual. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2002-123.

- NIOSH [1998]. Worker Deaths by Electrocution, A Summary of NIOSH Surveillance and Investigative Findings. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 98-131.

- Code of Federal Regulations 2003 edition. 29 CFR 1926.32(f). General Safety and Health Provisions. U.S. Printing Office, Office of the Federal Register, Washington, D.C.

- Code of Federal Regulations 2003 edition. 29 CFR 1926.21(b)(2). Safety Training and Education. U.S. Printing Office, Office of the Federal Register, Washington, D.C.

- Code of Federal Regulations 2003 edition. 29CFR 1926.50 (c) Medical Services and First Aid. U.S. Printing Office, Office of the Federal Register, Washington, D.C.

- Anonymous. Labels in English Pose Risk in Multilingual Nation. New York: NY ; The New York Times, May 20, 2001.

- Kelly Langdon [2003] Making the workplace safe for Spanish-speaking employees. Contributing writer Metal Fabricating Source, Thefabricator.com, June 26, 2003. Fabricators & Manufacturers Association, Rockford, IL.

- Lopez M., University of Maryland, School of Public Affairs and Mora M., New Mexico State University, Department of Economics & International Business [1998]. The Labor Market Effects of Bilingual Education Among Hispanic Workers.

- The Center to Protect Workers’ Rights [2002]. The Construction Chart Book, 3rd Edition, Hispanic Workers in Construction and Other Industries. Silver Spring, MD: The Center to Protect Workers’ Rights.

Back to Top

Investigator Information

This investigation was conducted by Nancy T. Romano and Doloris N. Higgins, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation Team, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research.