Key points

- Kawasaki disease (KD) is a severe illness with very specific signs and symptoms.

- It occurs mostly in children younger than 5 years old and affects boys more often than girls.

- KD can cause heart and blood vessel damage, and it is the #1 cause of acquired heart disease in children in the US

- Most children recover with treatment.

- Speak with a healthcare provider if your child has symptoms of KD.

Overview

Kawasaki disease (KD), also known as Kawasaki syndrome, is a disease that can cause damage to the heart and blood vessels, mostly in children younger than 5 years old. It affects boys more often than girls. The cause of KD is not known.

In the continental United States, KD occurs in about 9 to 20 per 100,000 children under 5 years of age.

In 2019, there were more than 5,000 children under 18 years of age who were hospitalized with KD in the United States. Of these children, nearly 3,700 were under 5 years of age.

Signs and symptoms

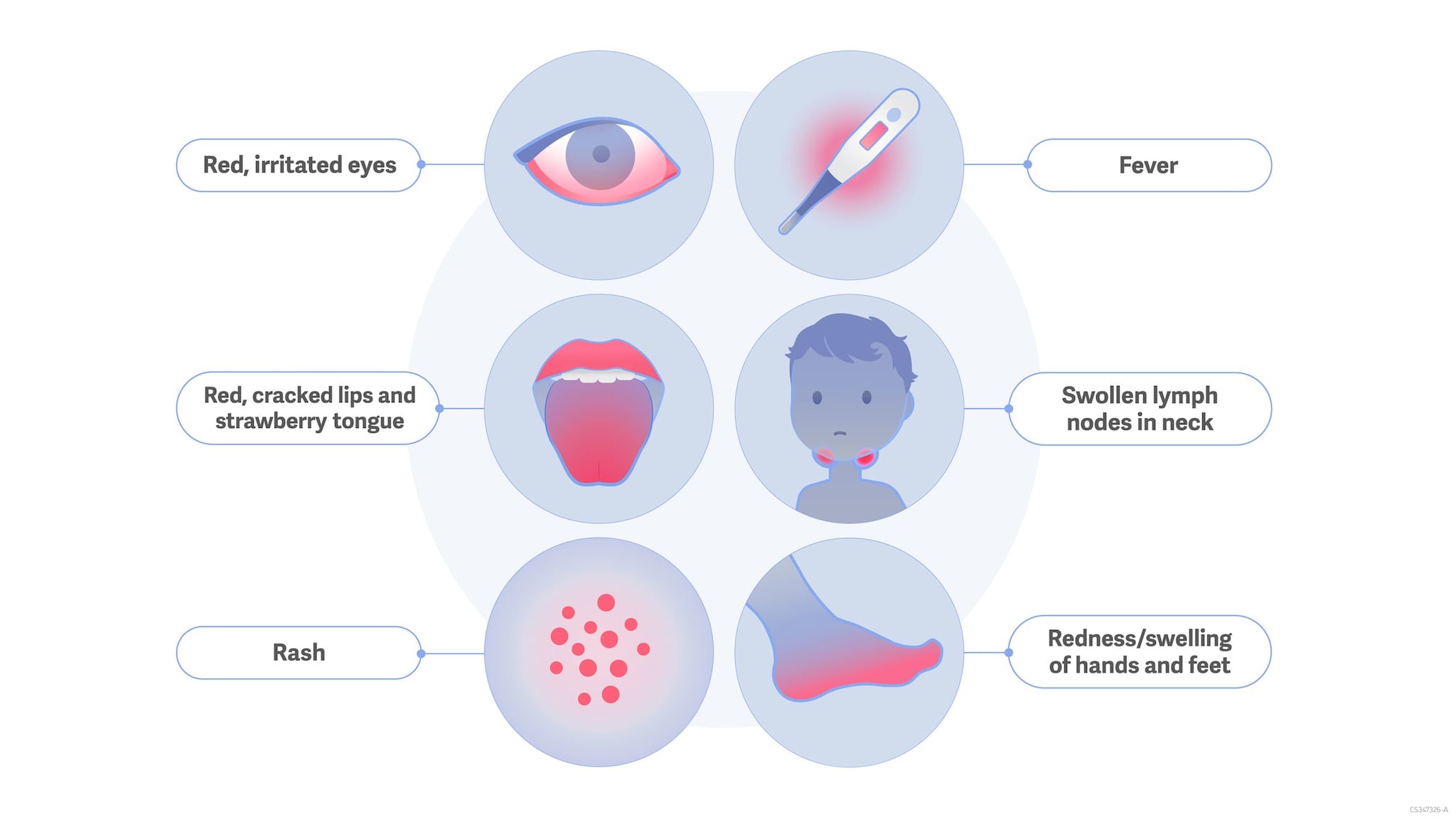

Children with KD have a fever that typically lasts for 5 days or longer. They may also have some or all of the following symptoms:

- Rash

- Swelling and redness of their hands and feet

- Irritation and redness of the whites of their eyes

- Swollen lymph glands in their neck

- Irritation and inflammation of their mouth, lips, and throat

KD can cause serious complications, including swelling of parts of the heart and other blood vessels. When this happens, the heart doesn't work as well to pump blood to the body and could burst (coronary artery dilation and aneurysms).

Atypical Kawasaki disease

Patients whose illness does not meet the criteria for KD but have fever and abnormal coronary artery concerns are classified as having atypical or incomplete KD.

Treatment and recovery

Treatment for KD is available, and it must be given at the hospital. It typically combines a mixture of antibodies given through your veins (intravenous immunoglobulin) and aspirin. The treatment can help make symptoms less severe and reduce the risk of serious complications. Healthcare professionals may recommend additional treatments.

Most children recover with proper treatment.

- McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, Kobayashi T. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-99.

- Maddox RA, Person MK, Kennedy JL, Leung J, Abrams JY, Haberling DL, Schonberger LB, Belay ED. Kawasaki Disease and Kawasaki Disease Shock Syndrome Hospitalization Rates in the United States, 2006-2018. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021 Apr 1;40(4):284-288. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002982. PMID: 33264213.

- Ae R, Makino N, Kuwabara M, Matsubara Y, Kosami K, Sasahara T, Nakamura Y. Incidence of Kawasaki disease before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Results of the 26th Nationwide Survey, 2019 to 2020. JAMA pediatrics. 2022 Dec 1;176(12):1217-24.

- Patel A, Holman RC, Callinan LS, Sreenivasan N, Schonberger LB, Fischer TK, Belay ED. Evaluation of clinical characteristics of Kawasaki syndrome and risk factors for coronary artery abnormalities among children in Denmark. Acta Paediatr. 2013 Apr;102(4):385-390. doi: 10.1111/apa.12142. Epub 2013 Jan 21.

- Callinan LS, Tabnak F, Holman RC, Maddox RA, Kim JJ, Schonberger LB, Vugia DJ, Belay ED. Kawasaki syndrome and factors associated with coronary artery abnormalities in California. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 Sep;31(9):894-898.

- Holman RC, Christensen KY, Belay ED, Steiner CA, Effler PV, Miyamura J, Forbes S, Schonberger LB, Melish M. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Incidence of Kawasaki Syndrome among Children in Hawaii. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2010;69:194-197.

- Holman RC, Curns AT, Belay ED, Steiner CA, Effler PV, Yorita KL, Miyamura J, Forbes S, Schonberger LB, Melish M. Kawasaki syndrome in Hawaii. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(5):429-433.

- Belay ED, Maddox RA, Holman RC, Curns AT, Ballah K, Schonberger LB. Kawasaki syndrome and risk factors for coronary artery abnormalities, United States, 1994-2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(3):245-249.

- Belay ED, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, DeStefano F, Shahriari A, Davis RL, Rhodes PH, Thompson RS, Black SB, Shinefield HR, Marcy SM, Ward JI, Mullooly JP, Chen RT, Schonberger LB. The incidence of Kawasaki syndrome in West Coast health maintenance organizations.Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:828-832.

- Bronstein DE, Dille AN, Austin JP, Williams CM, Palinkas LA, Burns JC. Relationship of climate, ethnicity and socioeconomic status to Kawasaki disease in San Diego County, 1994 through 1998. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1087-1091.

- Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Kawasaki syndrome. Clin Microbiol. Rev 1998;11:405-414.

- Melish ME, Hicks RM, Larson EJ. Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome in the United States.Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:599-607.

- Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271-276.