Treatment of Plasmodium Infections in Nonhuman Primates Imported under 42 CFR § 71.53

Date: January 20, 2023

Subject

CDC policy statement: Treatment of Plasmodium infections in nonhuman primates (NHPs) imported under 42 CFR § 71.53

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Global Migration Health (DGMH) administers regulations governing the importation of nonhuman primates (NHPs) into the United States.

Authority

Under the authority of section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. § 264), the Secretary of Health and Human Services is authorized to make and enforce regulations to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the United States and from one U.S. state or territory into any other U.S. state or territory. Federal quarantine regulations (42 CFR § 71.53) restrict the importation of NHPs into the United States. Under these regulations, importers of NHPs must register with CDC and implement infection control measures. They may only import and distribute NHPs for bona fide scientific, educational, or exhibition purposes, as defined in the regulations.

Background

CDC has received inquiries from CDC-registered importers regarding screening imported NHPs for malaria, using tests (e.g., PCR or blood smears) that detect the presence of parasites in the Plasmodium genus, during the CDC-mandated quarantine period. Please note that, other than tuberculosis, CDC does not currently require screening tests to be performed in apparently healthy NHPs during the CDC-mandated quarantine period. If importers choose to screen apparently healthy animals for Plasmodium infection during the quarantine period, positive results must be reported to CDC. Although testing apparently healthy animals for Plasmodium infection during quarantine is optional, importers are reminded that NHPs that develop clinical signs of malaria during quarantine MUST undergo appropriate diagnostic testing to identify the cause of illness.

Due to concerns over the introduction of Plasmodium parasites that may cause malaria in humans, treatment to eliminate the infection will be required before infected animals are released from CDC-mandated quarantine. CDC has developed a protocol for treating NHPs identified to be infected with Plasmodium during quarantine. The protocol considers what is currently known about the biological behavior of Plasmodium species (including simian species), presence of vector species in the U.S., potential for drug resistance, zoonotic potential, and availability of validated tests. Currently, of the simian Plasmodium species, Plasmodium knowlesi, P. cynomolgi, P. coatneyi, and P. inui have been reported to cause disease in humans. Other species are suspected to have zoonotic potential, but validated laboratory methods have not yet been developed to reliably identify these species.

If an NHP is identified as having a Plasmodium infection, ideally the species of the parasite should be identified to guide treatment decisions. In humans and NHPs, P.vivax, P. ovale, and P. cynomolgi are currently known to produce hypnozoite liver stages in addition to the blood stages of the parasite. If the liver stages aren’t adequately treated, the infected individual is prone to relapsing disease, especially if the individual becomes immunocompromised. In most parts of the world, P. falciparum and, in select countries, P. vivax have shown resistance to the antimalarial drug chloroquine. In some parts of Southeast Asia, P. falciparum is resistant to mefloquine, so other antimalarials are required to treat these infections.

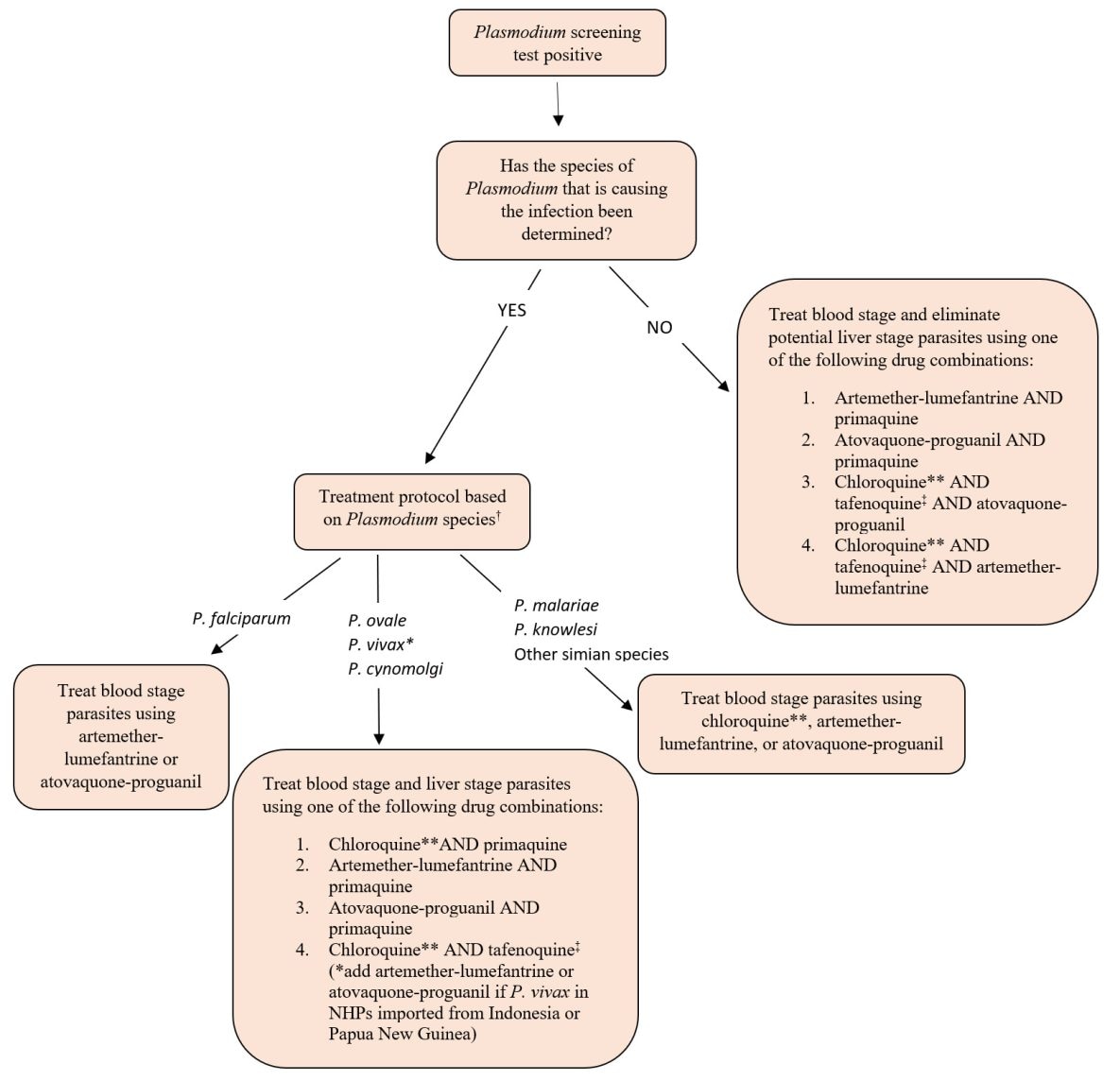

Unfortunately, a validated diagnostic test to speciate both human and simian Plasmodium isn’t currently readily available. Until such a test becomes widely available, infected NHPs should be treated using an antimalarial protocol that considers the potential for antimalarial resistance and the need to eliminate BOTH blood stages AND potential liver stages of Plasmodium. An algorithm is provided below that guides treatment decisions based on diagnostic test results available to the treating veterinarian.

Policy statement

CDC-registered importers who choose to screen apparently healthy animals for malaria during the CDC-mandated quarantine period must report positive results to CDC within 24 hours.

Importers reporting Plasmodium-positive NHPs during the CDC-mandated quarantine period will be required to adhere to the following treatment algorithm before the infected animals will be released from quarantine. If NHP dosing regimens aren’t available in animal drug formularies or peer reviewed literature, the treating veterinarian may consider extrapolating from published human pediatric doses off-label (see https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/resources/pdf/Malaria_Treatment_Table_202306.pdf [PDF – 10 pages]) [1]. Please note that, in most cases, CDC will not require animals to be retested after treatment.

For additional information regarding treatment of Plasmodium infections or to report positive test results in NHPs in CDC-mandated quarantine, contact CDC Division of Global Migration Health by emailing NHPImporters@cdc.gov. For information regarding treatment of ill NHPs with malaria, contact the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria by calling the malaria hotline at 770-488-7788 (M-F 9a-5p) or the Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100 (24/7; ask for the on-call malaria clinician).

[1] NOTE that tafenoquine is not approved for human pediatric use.

Treatment Algorithm for NHPs Identified with Plasmodium Infections During CDC-mandated Quarantine

† A validated test for simian Plasmodium speciation isn’t currently available.

* Use artemether-lumefantrine or atovaquone-proguanil to treat blood stage of P. vivax in NHPs imported from Indonesia or Papua New Guinea. P. vivax in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea have resistance to the antimalarial drug chloroquine.

** Hydroxychloroquine can be used as an alternative to chloroquine.

‡ Dow et al. Malaria Journal 2011, 10:212. http://www.malariajournal.com/content/10/1/212