Social Determinants of Health among Adults with Diagnosed HIV Infection in the United States and Puerto Rico, 2021: Special Focus Profiles

The Special Focus Profiles section highlights disparities in rates of HIV diagnoses by SDOH variables, including income inequality, and factors for special consideration in addressing health disparities that may be of particular interest to HIV prevention programs in state and local health departments.

Health Disparities

Health disparities are systematic, plausibly avoidable differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and causes of a disease and the related adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups [5]. Reducing health disparities, achieving health equity, and improving the health of all U.S. population groups are major goals of public health.

Most health disparities are related to SDOH, the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age [4]. Identification and awareness of differences among population health determinants and health outcomes are essential steps toward reducing health disparities. Recent CDC reports show disparities by selected characteristics in many of the indicators for the EHE and NHAS initiatives [20, 21]. Success in achieving the goals of these initiatives will be determined to some extent by how effectively federal, state, and local agencies and private organizations work with communities to eliminate health disparities among populations experiencing a disproportionate burden of disease, disability, and death.

See Technical Notes for additional information on disparity measures and how the disparities were calculated.

Disparities—Poverty/Wealth, by Assigned Sex at Birth and Race/Ethnicity

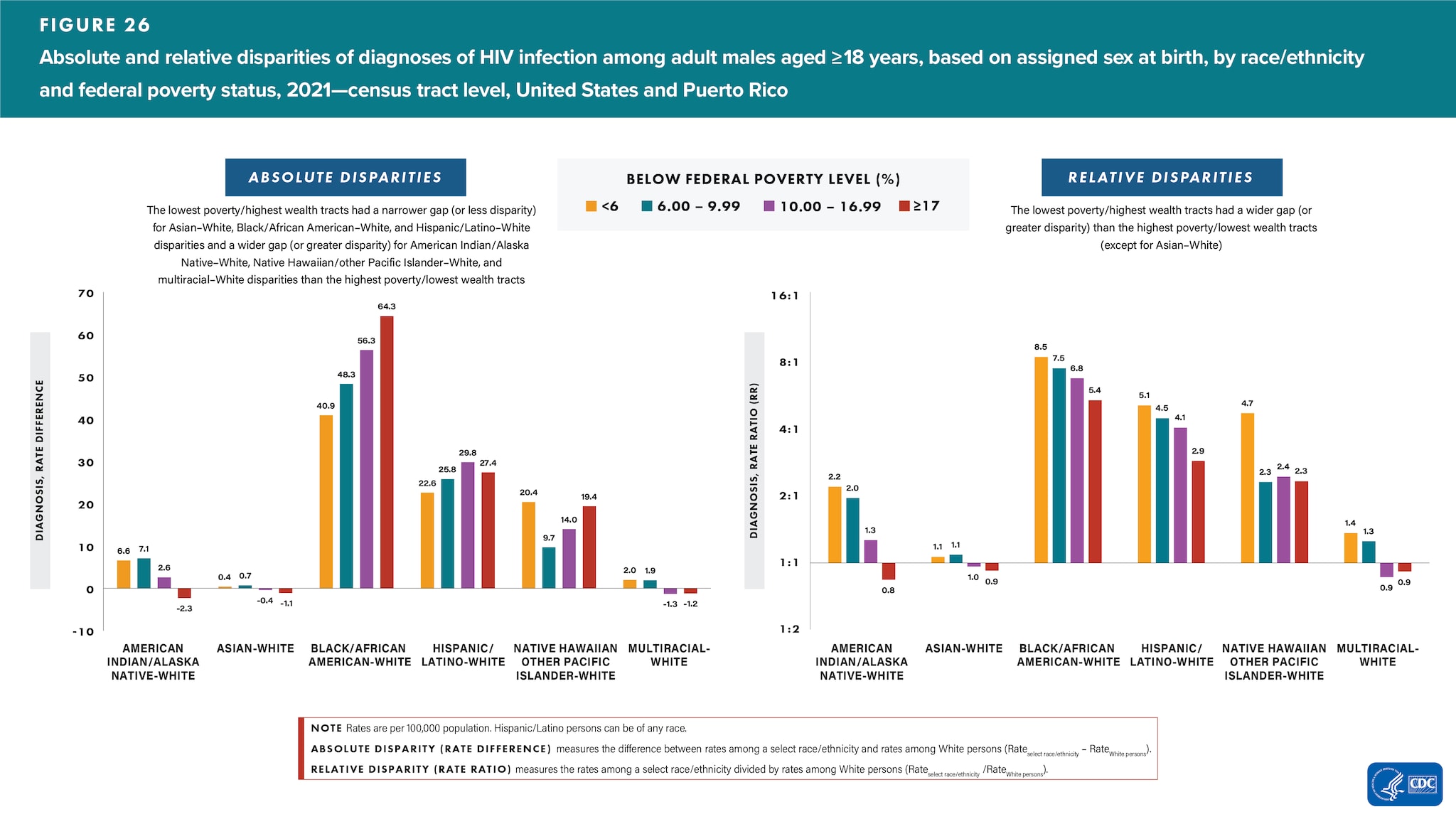

Male

Highest poverty/lowest wealth―Among males residing in tracts with the highest poverty/lowest wealth, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 5.4 times, Hispanic/Latino 2.9 times, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 2.3 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.2 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native and 1.1 times as high as the rate for both Asian and multiracial males (Figure 26 and Table 2).

Lowest poverty/highest wealth―Among males residing in tracts with the lowest poverty/highest wealth, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 2.2 times, Asian 1.1 times, Black/African American 8.5 times, Hispanic/Latino 5.1 times, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 4.7 times, and multiracial males 1.4 times as high as the rate for White males (Figure 26 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White males were as follows: the lowest poverty/highest wealth tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) for Asian–White, Black/African American–White, and Hispanic/Latino–White disparities and a wider gap (or greater disparity) for American Indian/Alaska Native–White, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander–White, and multiracial–White disparities than the highest poverty/lowest wealth tracts (Figure 26).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White males were as follows: the lowest poverty/highest wealth tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than the highest poverty/lowest wealth tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 26).

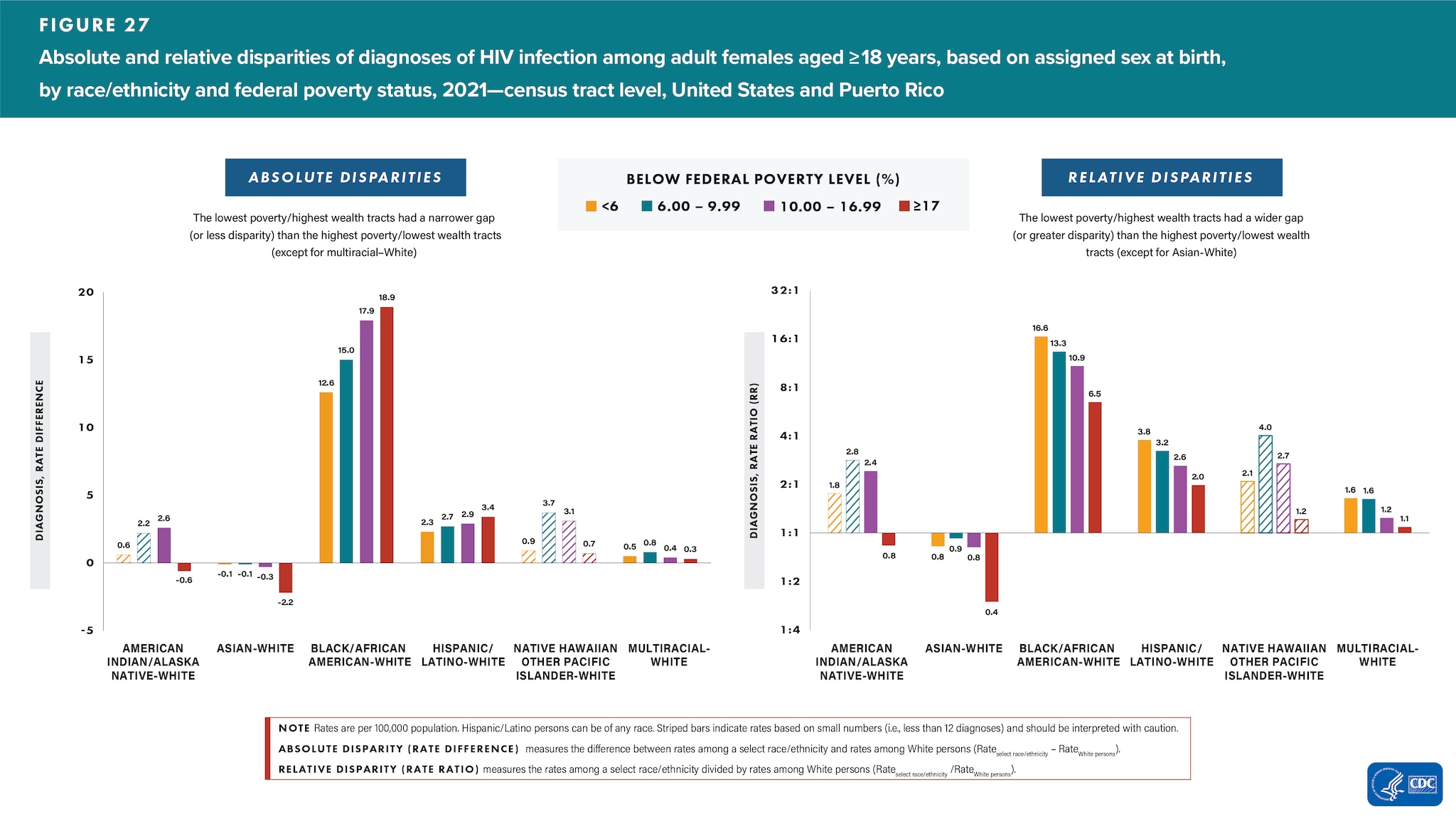

Female

Highest poverty/lowest wealth―Among females residing in tracts with the highest poverty/lowest wealth, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 6.5 times, Hispanic/Latino 2.0 times, and multiracial females 1.1 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.2 times and 2.7 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian females, respectively (Figure 27 and Table 2).

Lowest poverty/highest wealth―Among females residing in tracts with the lowest poverty/highest wealth, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 16.6 times, Hispanic/Latino 3.8 times, and multiracial females 1.6 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.2 times as high as the rate for Asian females (Figure 27 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White females were as follows: the lowest poverty/highest wealth tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than the highest poverty/lowest wealth tracts (except for multiracial–White) (Figure 27).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White females were as follows: the lowest poverty/highest wealth tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than the highest poverty/lowest wealth tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 27).

Disparities—Education, by Assigned Sex at Birth and Race/Ethnicity

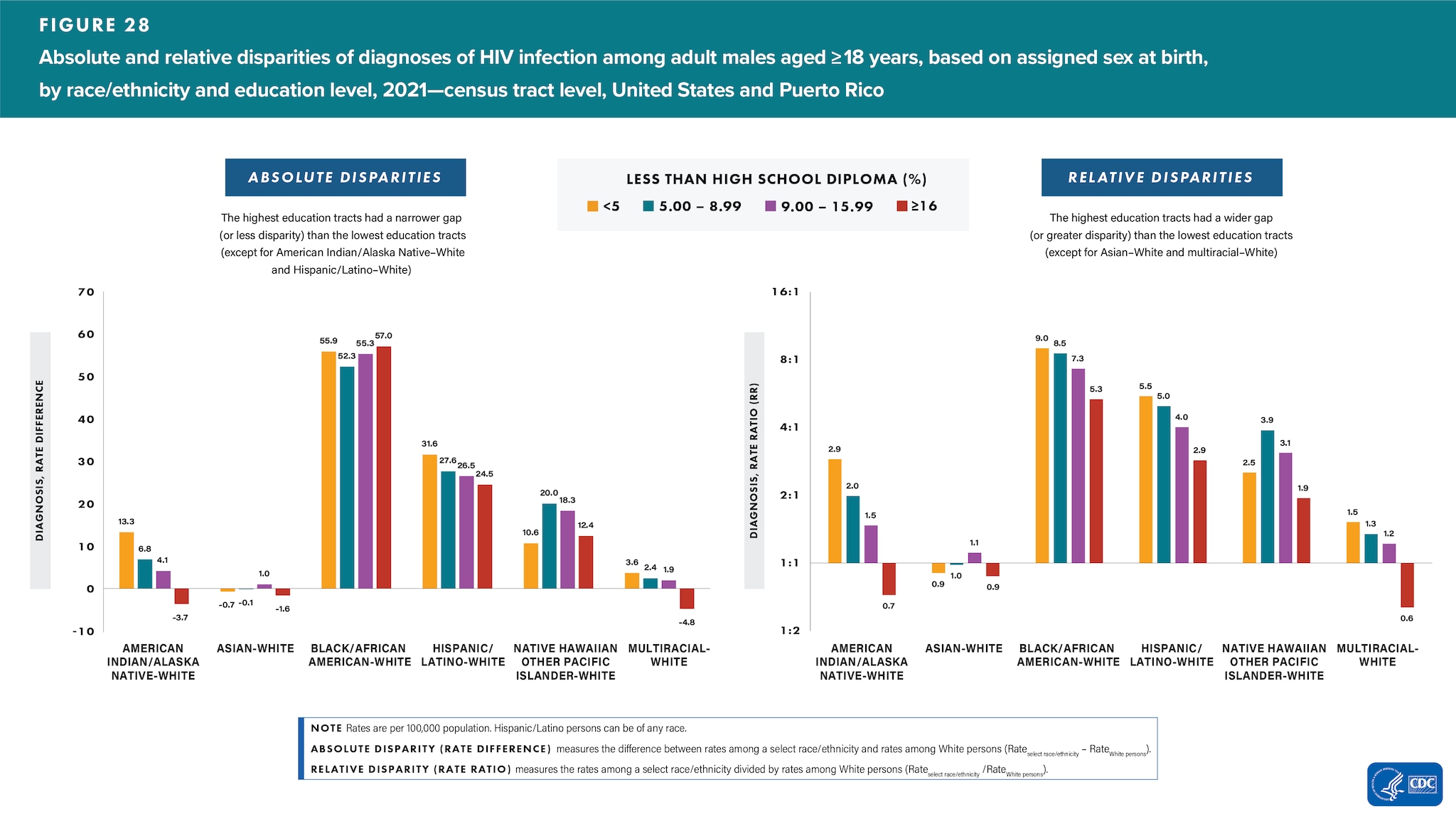

Male

Lowest education―Among males residing in tracts with the lowest education, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 5.3 times, Hispanic/Latino 2.9 times, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander males 1.9 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.4 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native, 1.1 times for Asian, and 1.6 times for multiracial males (Figure 28 and Table 2).

Highest education―Among males residing in tracts with the highest education, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 2.9 times, Black/African American 9.0 times, Hispanic/Latino 5.5 times, Native American/Alaska Native 2.5 times, and multiracial males 1.5 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.1 times as high as the rate for Asian males (Figure 28 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White males were as follows: the highest education tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the lowest education tracts (except for American Indian/Alaska Native–White and Hispanic/Latino–White) (Figure 28).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White males were as follows: the highest education tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the lowest education tracts (except for Asian–White and multiracial–White) (Figure 28).

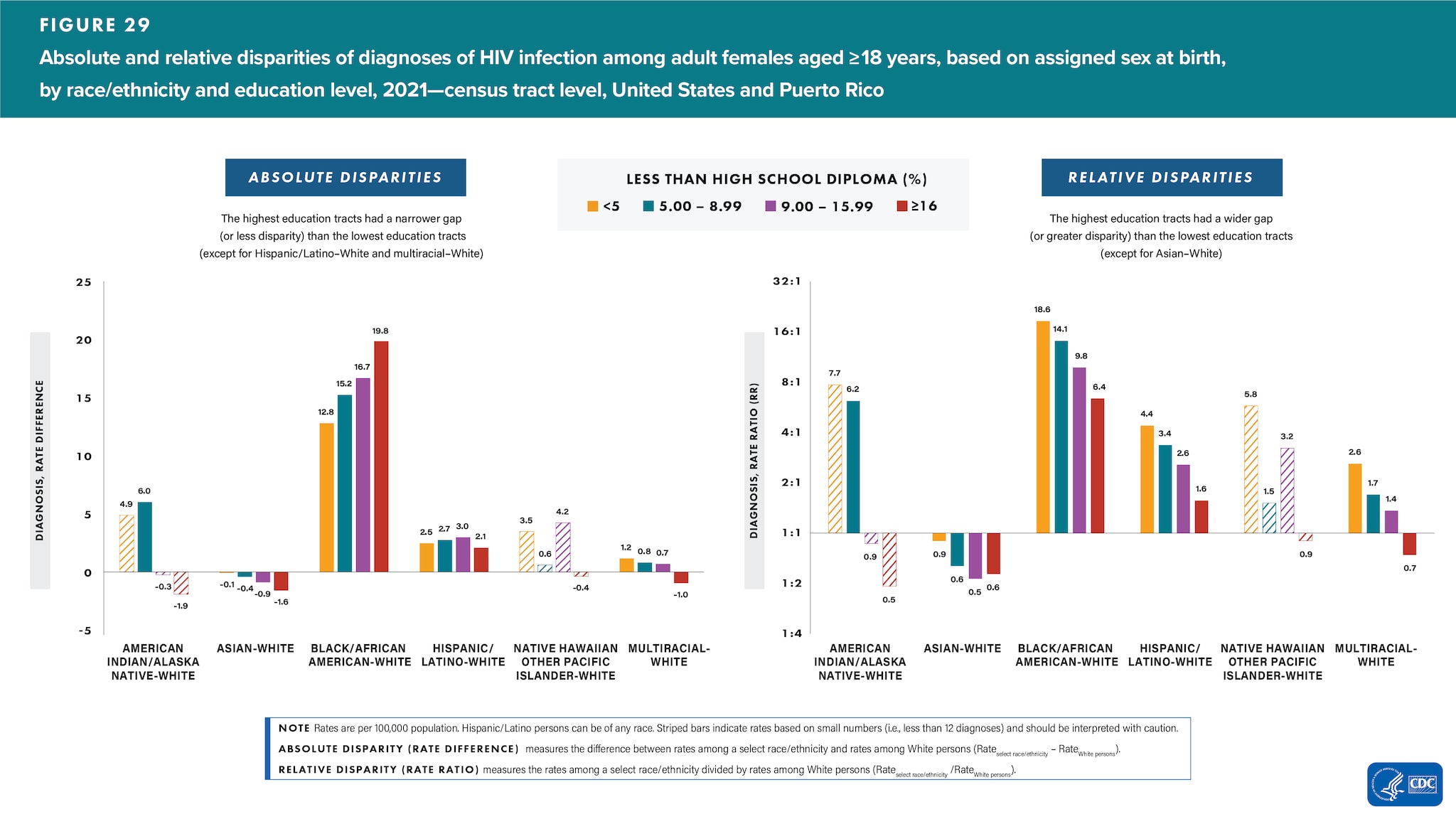

Female

Lowest education―Among females residing in tracts with the lowest education, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 6.4 times and Hispanic/Latino 1.6 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.8 times and 1.4 times as high as the rate for Asian and multiracial females, respectively (Figure 29 and Table 2).

Highest education―Among females residing in tracts with the highest education, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 18.6 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.4 times, and multiracial females 2.6 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.1 times as high as the rate for Asian females (Figure 29 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White females were as follows: the highest education tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the lowest education tracts (except for Hispanic/Latino–White and multiracial–White) (Figure 29).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White females were as follows: the highest education tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the lowest education tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 29).

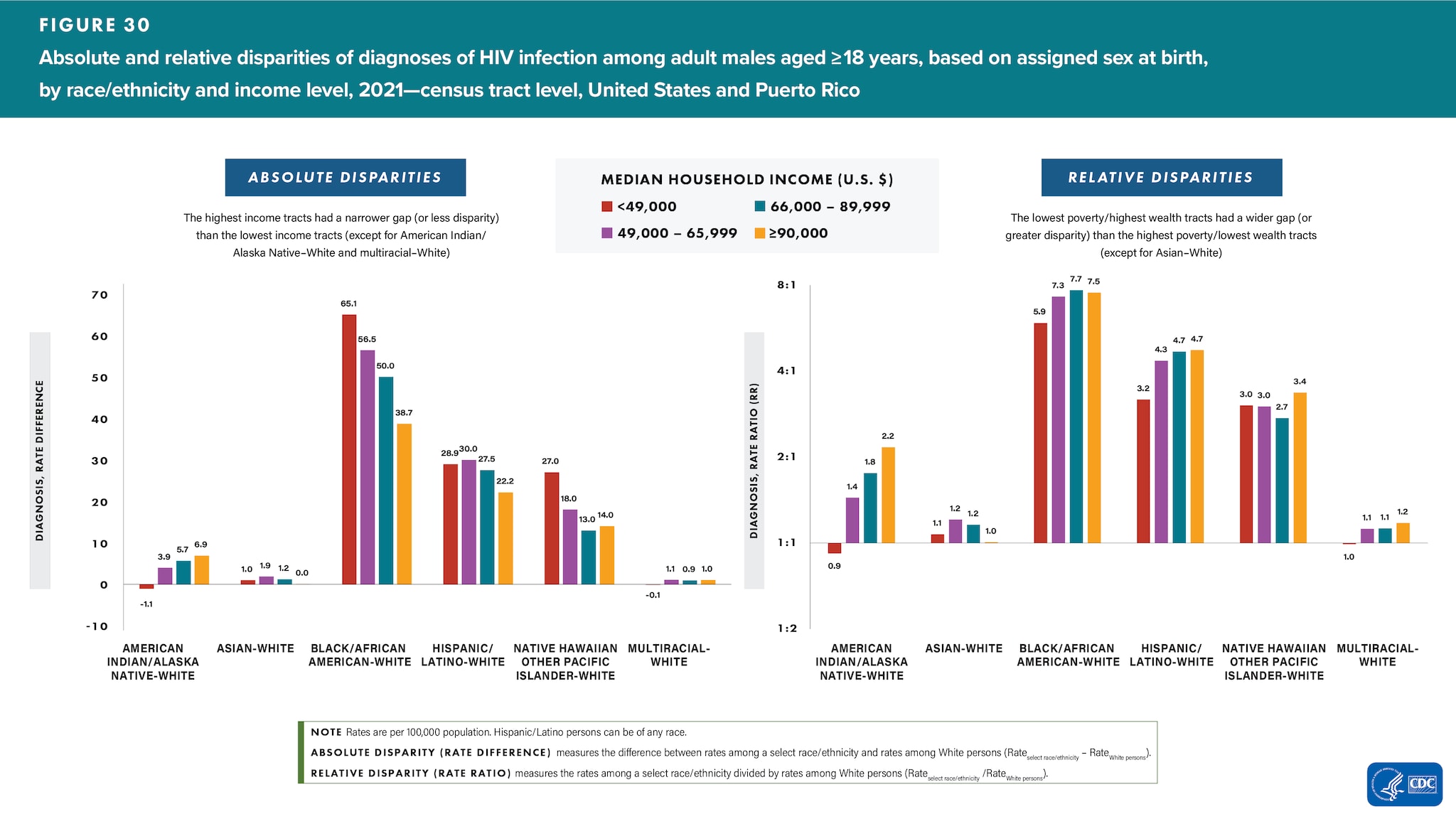

Disparities—Income, by Assigned Sex at Birth and Race/Ethnicity

Male

Lowest income―Among males residing in tracts with the lowest income, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Asian 1.1 times, Black/African American 5.9 times, Hispanic/Latino 3.2 times, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander males 3.0 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.1 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native males; and White and multiracial males had similar rates (Figure 30 and Table 2).

Highest income―Among males residing in tracts with the highest income, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 2.2 times, Black/African American 7.5 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.7 times, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 3.4 times, and multiracial males 1.2 times as high as the rate for White males; White and Asian males had similar rates (Figure 30 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White males were as follows: the highest income tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the lowest income tracts (except for American Indian/Alaska Native–White and multiracial–White) (Figure 30).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White males were as follows: the highest income tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the lowest income tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 30).

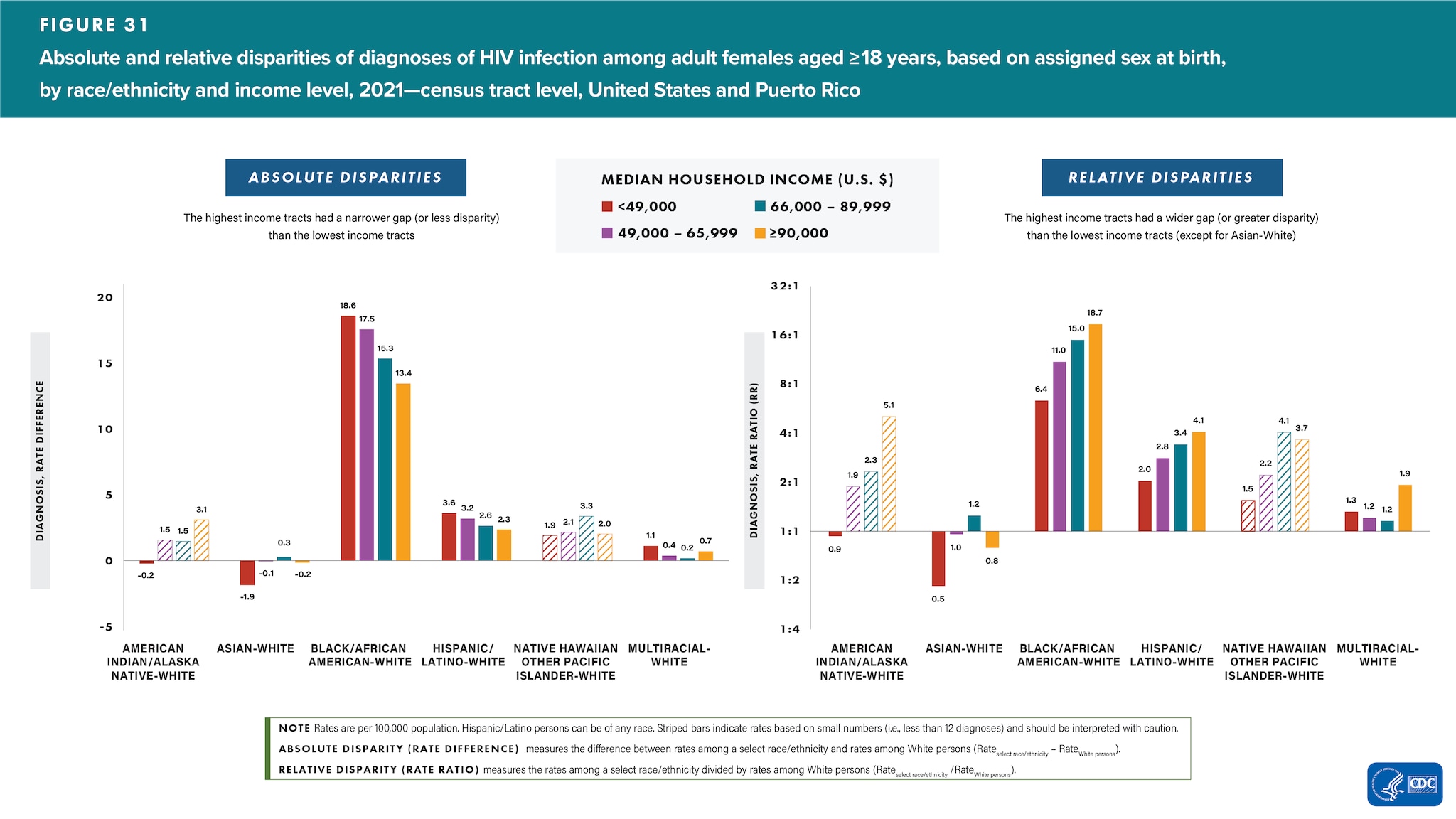

Female

Lowest income―Among females residing in tracts with the lowest income, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 6.4 times, Hispanic/Latino 2.0 times, and multiracial females 1.3 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.1 times and 2.2 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian females, respectively (Figure 31 and Table 2).

Highest income―Among females residing in tracts with the highest income, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 18.7 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.1 times, and multiracial females 1.9 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.3 times as high as the rate for Asian females (Figure 31 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White females were as follows: the highest income tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the lowest income tracts (Figure 31).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White females were as follows: the highest income tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the lowest income tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 31).

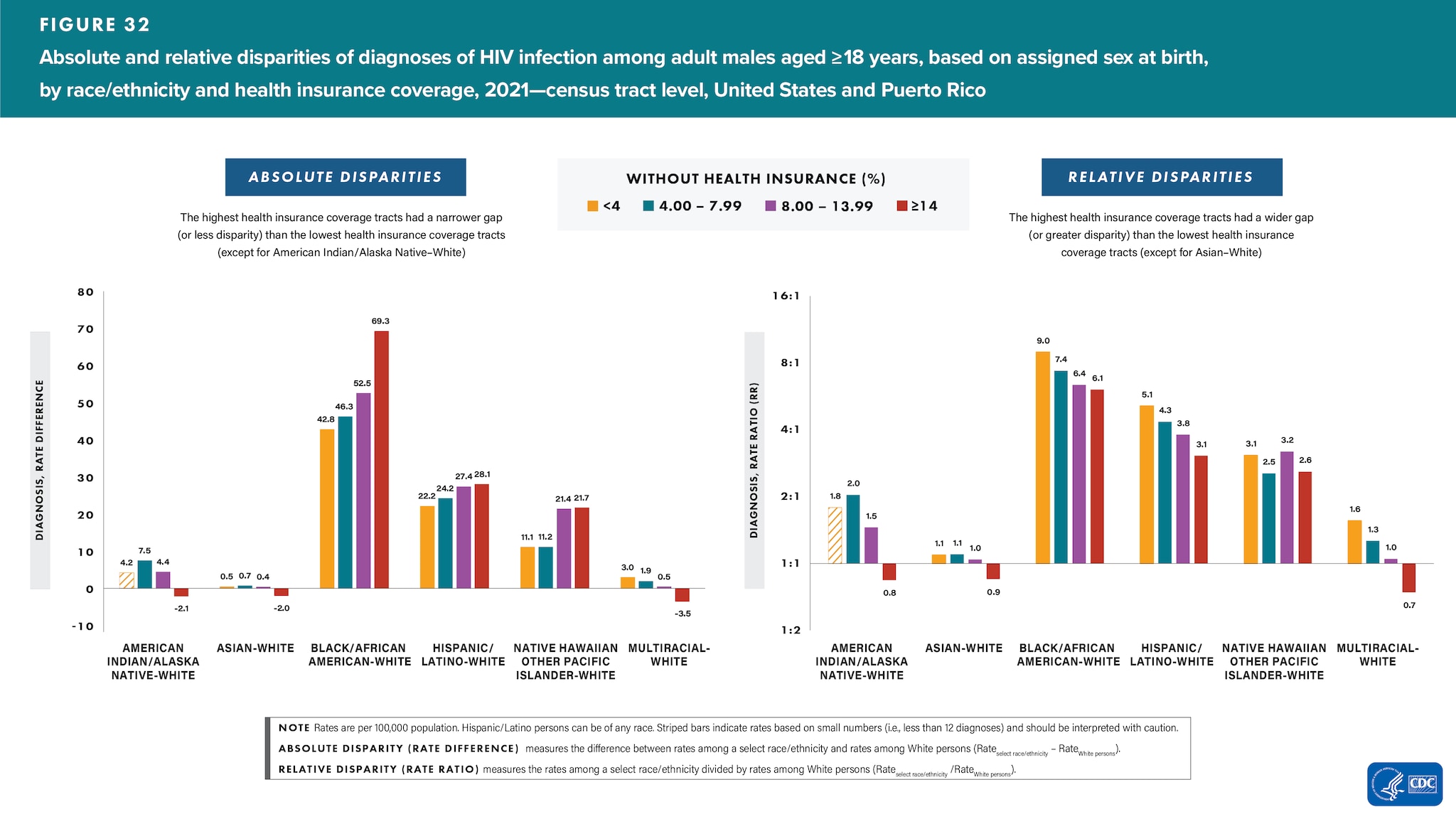

Disparities—Health Insurance Coverage, by Assigned Sex at Birth and Race/Ethnicity

Male

Lowest health insurance coverage―Among males residing in tracts with the lowest health insurance coverage, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 6.1 times, Hispanic/Latino 3.1 times, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander males 2.6 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.2 times as high as the rates for both American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian males and 1.3 times as high as the rates for multiracial males (Figure 32 and Table 2).

Highest health insurance coverage―Among males residing in tracts with the highest health insurance coverage, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Asian 1.1 times, Black/African American 9.0 times, Hispanic/Latino 5.1 times, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 3.1 times, and multiracial males 1.6 times as high as the rate for White males (Figure 32 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White males were as follows: the highest health insurance coverage tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the lowest health insurance coverage tracts (except for American Indian/Alaska Native–White) (Figure 32).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White males were as follows: the highest health insurance coverage tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the lowest health insurance coverage tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 32).

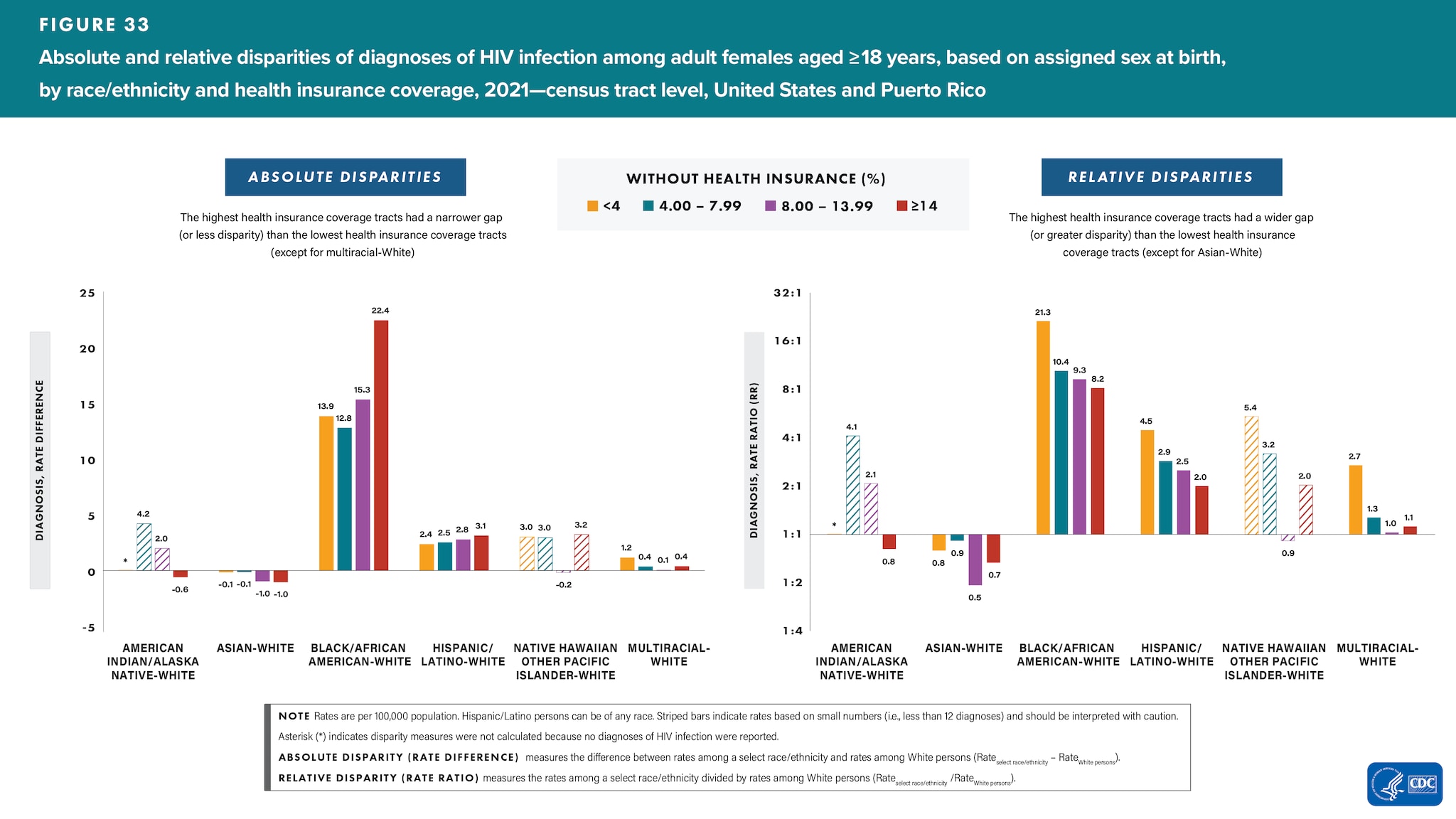

Female

Lowest health insurance coverage―Among females residing in tracts with the lowest health insurance coverage, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 8.2 times, Hispanic/Latino 2.0 times, and multiracial females 1.1 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.2 times and 1.5 times as high as the rate for American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian females, respectively (Figure 33 and Table 2).

Highest health insurance coverage―Among females residing in tracts with the highest health insurance coverage, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 21.3 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.5 times, and multiracial females 2.7 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.3 times as high as the rate for Asian females (Figure 33 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White females were as follows: the highest health insurance coverage tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than the lowest health insurance coverage tracts (except for multiracial-White) (Figure 33).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White females were as follows: the highest health insurance coverage tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than the lowest health insurance coverage tracts (except for Asian–White) (Figure 33).

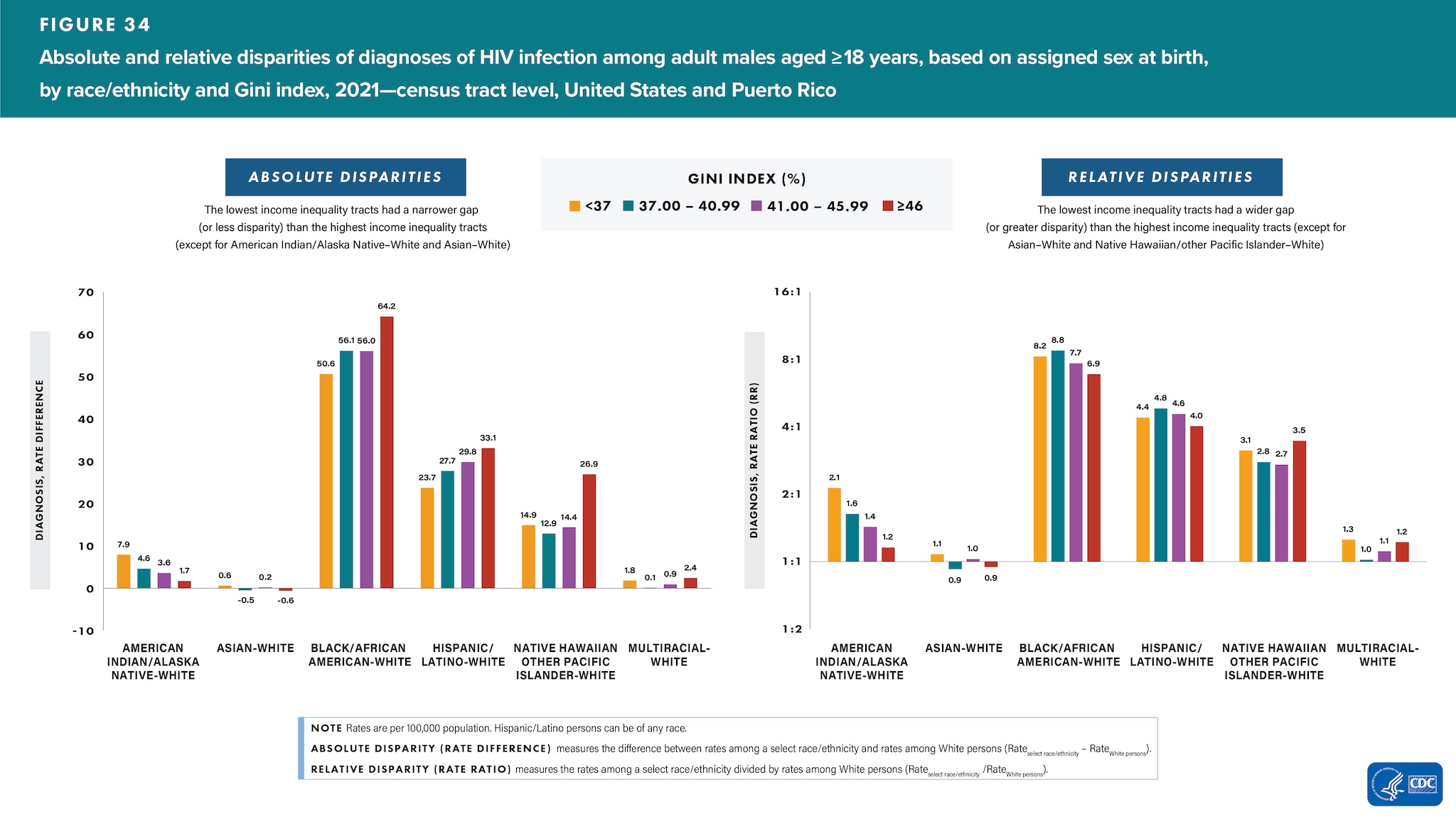

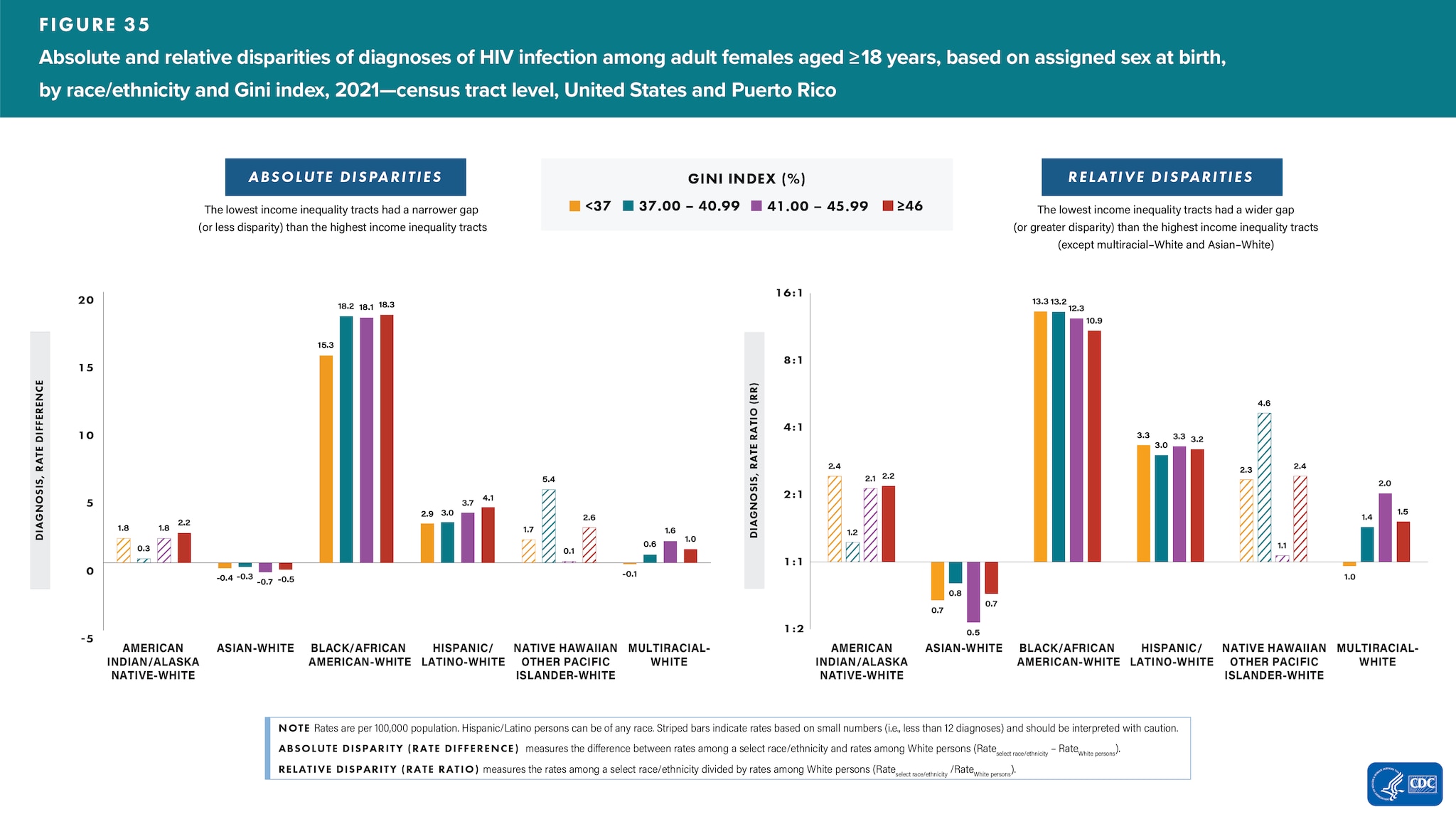

Disparities—Income Inequality, by Assigned Sex at Birth and Race/Ethnicity

Male

Highest income inequality―Among males residing in tracts with the highest income inequality, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 1.2 times, Black/African American 6.9 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.0 times, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 3.5 times, and multiracial males 1.2 times as high as the rate for White males; the rate for White males was 1.1 times as high as the rate for Asian males (Figure 34 and Table 2).

Lowest income inequality―Among males residing in tracts with the lowest income inequality, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 2.1 times, Asian 1.1 times, Black/African American 8.2 times, Hispanic/Latino 4.4 times, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander 3.1, and multiracial males 1.3 times as high as the rate for White males (Figure 34 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White males were as follows: the lowest income inequality tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than in the highest income inequality tracts (except for American Indian/Alaska Native–White and Asian–White) (Figure 34).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White males were as follows: the lowest income inequality tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than in the highest income inequality tracts (except for Asian–White and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander–White) (Figure 34).

Female

Highest income inequality―Among females residing in tracts with the highest income inequality, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native 2.2 times, Black/African American 10.9 times, Hispanic/Latino 3.2 times, and multiracial females 1.5 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.4 times as high as the rate for Asian females (Figure 35 and Table 2).

Lowest income inequality―Among females residing in tracts with the lowest income inequality, the relative disparities (rate ratios) in HIV diagnosis rates were as follows: Black/African American 13.3 times and Hispanic/Latino 3.3 times as high as the rate for White females; the rate for White females was 1.5 times as high as the rate for Asian females; White and multiracial females had similar rates (Figure 35 and Table 2).

Changes in disparities

- For absolute disparities, the difference between rates among a select race/ethnicity and rates among White females were as follows: the lowest income inequality tracts had a narrower gap (or lesser disparity) than the highest income inequality tracts (Figure 35).

- For relative disparities, the rates among a select race/ethnicity divided by rates among White females were as follows: the lowest income inequality tracts had a wider gap (or greater disparity) than the highest income inequality tracts (except multiracial–White and Asian–White) (Figure 35).

Health Disparities Special Considerations

Accurate and timely assessment and monitoring of the magnitude and direction of change of health disparities and their determinants are necessary for evaluation of progress toward the Healthy People 2030 goals of eliminating health disparities, achieving health equity, and attaining health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all [22]. Overall, disparities in HIV are not improving for select populations in the United States [23]. While both downstream and upstream interventions are important, evidence from systematic reviews suggests that downstream prevention interventions (directed at individual-level factors) are more likely than upstream interventions (directed at social- or policy-level factors) to increase health disparities [24].

Below are some important upstream factors, which can lead to downstream and upstream interventions, for special consideration when addressing and reducing health disparities related to poverty, education, income, and health care status among adults aged ≥18 years with diagnosed HIV infection.

Residential Segregation

The persistence of racial differences in health, for which individual differences in socioeconomic status (SES) are known, may reflect the role that residential segregation and neighborhood quality can play in racial disparities in health. As a result of segregation, higher-income Black/African American persons live in lower-income areas than White persons of similar economic status, and lower-income White persons live in higher-income areas than Black/African American persons of similar economic status [24]. Other racial/ethnic groups experience less residential segregation than Black/African American persons, and although residential segregation is inversely related to income for Hispanic/Latino and Asian persons, the segregation of Black/African American persons is high at all levels of income [24]. Black/African American persons with the highest levels of income experience more residential segregation than Hispanic/Latino and Asian persons with the lowest levels of income [24]. In addition to other SDOH variables, residential segregation may play a role in racial disparities in HIV diagnoses by isolating individuals from access to important resources and affecting neighborhood quality, with lower income and isolated areas being more vulnerable [25].

Medical Treatment

Hispanic/Latino persons account for one of the largest uninsured groups in the United States [26, 27], and about one-quarter of Hispanic/Latino adults do not have a primary care provider [26]. Additionally, Black/African American persons typically have the lowest linkage to HIV medical care [21]. Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino persons are less likely than White persons to receive high-quality medical treatment after they gain access to medical care [27, 28]. These patterns exist across a broad range of medical procedures and institutional contexts, and they are further compounded by factors like stigma, immigration status, and discrimination, all of which may contribute to disparities in HIV infections [28].

Psychosocial Stress

Exposure to psychosocial stressors (i.e., stress that may result from poverty, crime, racial discrimination, or other persistent difficulties) may explain the link between SES, race/ethnicity, and poor health outcomes. Chronic exposure to stress is associated with altered physiological functioning, which may increase risks for a broad range of health conditions. Individuals in lower income areas are more likely to report elevated levels of stress and may be more susceptible to the negative effects of stressors [28]. In addition, the subjective experience of discrimination is a neglected stressor that can adversely affect the health of some racial/ethnic populations. Discrimination may contribute to the elevated risk of disease that is sometimes observed among Black/African American persons [28]. Psychosocial stress may play a role in racial disparities in HIV diagnoses by altering physiological functions due to chronic exposure to stress among individuals living in lower income areas and experiencing discrimination [28].