Appendix B: Guiding Principles for Implementing Health Equity into CDC’s Global Work

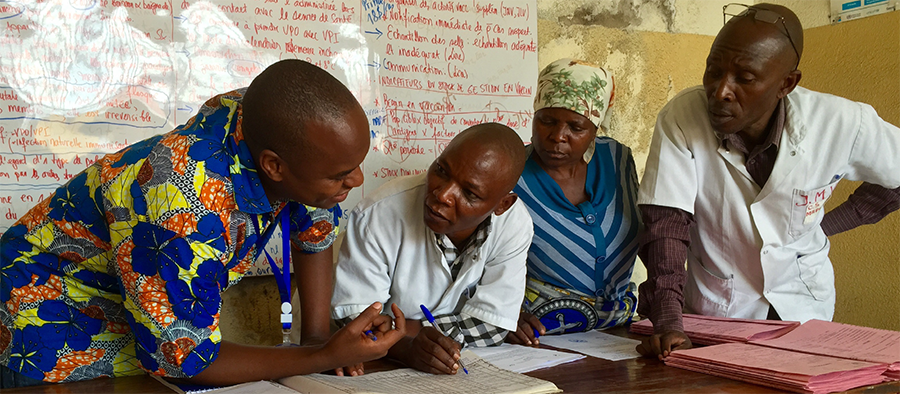

A CDC health worker (left) trains local healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A health equity (HE) strategy requires clear principles to guide scientific research, programs/interventions, and policies to not lose its focus. CDC is committed to the following principles:

- Prioritize the needs of people who are most disadvantaged – A HE approach requires that we prioritize populations/groups with the greatest needs first, with the aim towards greater equity recognizing that achieving greater equity benefits all of society [8]. For example, GID’s Global Immunization Strategic Framework Goal 1 is to “Strengthen immunization services to achieve high and equitable coverage”. GID’s approach focuses on populations with the highest burdens of vaccine-preventable diseases.” [23]. DGHT, through PEPFAR, supports countries that have been disproportionately impacted by HIV and TB and focuses on populations who are disproportionately impacted, including but not limited to, women, girls, orphans, men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, people who inject drugs, transgender people, and people in prison settings [26]. DPDM programs focus on malaria and other parasitic diseases among populations who are socio-economically disadvantaged. [24]. Since 1980, DGHP’s Field Epidemiology Training Program helped train over 18,000 disease detectives and develop capacities and capabilities in over 80 countries, many of which have among the poorest health indicators [28].

- Engage affected populations – It is very important that community members and relevant stakeholders are involved in the overall decision-making, ownership, and program and research design, planning, implementation, and evaluation process. This will ensure community acceptance of the program and help identify community resources that could potentially benefit the populations. Informed consent from every community member is impractical for some public health programs, such as water fluoridation. An alternative to obtaining informed consent would be to obtain the community’s consent. This can be done by engaging with representatives of the community through a town hall meeting or other forum where representatives of the community can participate in the public health decision-making. Formative research can be conducted before developing an intervention. This may include a literature review, community engagement, rapid ethnographic assessment, or focus group sessions, with the aim to clearly identify the health problem, develop clear goals and objectives, identify the appropriate target population, and the most effective strategy in dealing with the problem. Meaningfully engaging with communities ensures that our global work reflects the lived experiences of groups who have experienced historical and contemporary injustices. Maintaining community ownership, involvement, and participation throughout the life of the project is essential to program success.

- Collaboration with partners, including non-traditional and local partners, is essential to achieving sustainable health equity. An open letter from a group of African scientists, policy analysts, public health practitioners, and academics published in Nature Medicine criticizes a recent announcement of a $30 million grant awarded by the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) to fund activities related to improved use of data for decision-making to control and eliminate malaria in Africa [29]. Seven institutions from the US, UK, and Australia were funded as part of a consortium, but none were from Africa. The authors called for more equality and inclusion and advocate that such partnerships should be led by an African institution by African scientists. The principle of engaging affected populations is critical to the success and sustainability of programs. As noted by the authors of the open letter, engaging local partners benefits the programs because programs would be informed by their lived experiences and accumulated knowledge. Individuals living in a community have insights about their community that outsiders normally do not. The American Public Health Association (APHPA) Public Health Code of Ethics emphasizes the importance of the “community” and the interdependence of people [31]. An example of CDC’s global program that directly engaged local partners is DGHT global HIV funding through PEPFAR to health systems strengthening, providing nearly one billion US$ to over 40 countries [25]. This activity strengthens availability, accessibility, and acceptability of an array of health care and health-related services. CDC supports the transition of HIV services to local partners, with 70% of PEPFAR funding going to local partners by the end of 2020 [25]. Partners should be considered for their good standing with the community, good public health and human rights record, have qualified staff, good internal policies to protect privacy and confidentiality and other basic human rights, and network with other community organizations that provide various types of service to the community.

- Ensure programs do not heavily burden human rights – The late Jonathan Mann believed that “Public health practice is heavily burdened by the problem of inadvertent discrimination […] Indeed, inadvertent discrimination is so prevalent that all public health policies and programs should be considered discriminatory until proven otherwise, placing the burden on public health to affirm and ensure its respect for human rights”. Furthermore, Mann believed that “Public health has lacked a conceptual framework for identifying and analyzing the essential societal factors that represent the conditions in which people can be healthy” [30]. These beliefs inspired Mann to lead the global Health and Human Rights movement in the late 1980s to the 1990s. Particularly, Mann advocated incorporating international human rights language as a guiding framework for public health as it tries to address social determinants of health. According to Mann, “Modern human rights, […] seek to articulate the societal preconditions for human well-being, seem a far more useful framework, vocabulary, and form of guidance for public health efforts to analyze and respond directly to the societal determinants of health than any inherited from the past biomedical or public health tradition” [30]. Public health professionals often lack the knowledge and skills necessary to incorporate human rights into their work. They risk backlash if their programs and policies are implemented without serious human rights considerations. For example, a public health program that is unnecessarily too restrictive of human rights runs the risk of harming people, who in turn may become uncooperative and ultimately may lead to the program failure. Human rights respect and protection can help ensure programs’ success in many ways including: building a trusting relationship between the public and the public health practitioners; creating a more effective and conscientious public health workforce; and improving the effectiveness of public health programs.

- Ensure good and ethical public health practice – Not all public health programs are created equal. As stewards of the public funds, we must ensure that our research and programs build the evidence base and achieve greater health equity that is based on sound science and ethical principles [31]. We need to assess the program effectiveness in a given population, the cost and feasibility of implementation, the appropriateness and acceptability of the intervention in a given population, and whether the proposed strategies are culturally and ethically appropriate. The program must also take into consideration community-defined evidence, available community resources, other locally prioritized disease burdens, including social conditions affecting the community, and assess whether incorporating equity measures into existing program activities is feasible.

- Ensure ethical and knowledgeable staff – It is considered unethical for an unqualified/untrained person to practice medicine. Likewise, it is considered unethical to conduct public health programs and research if one lacks the skills and expertise to do so without guidance from a more experienced senior professional. We must ensure that knowledgeable, qualified, and respected individuals are involved in planning and implementation of programs. Individuals from the community, with considerations on background and perspective, must also be involved in these processes and should be considered for recruitment to build a diverse and equitable workforce.