National Networks Come Together to Help Prevent HPV-Related Cancers

The easiest way to fight cancer is to stop it before it starts. With this idea in mind, three national networks have come together to lower people’s risk of getting cancer in seven states.

The SelfMade Health Network, the Geographic Health Equity Alliance, and Nuestras Voces (Our Voices) networks are part of a consortium supported by CDC’s Networking2Save program. These networks launched the Tri-Network HPV Vaccination Learning Collaborative in September 2020 to help states learn how to increase HPV vaccine coverage.

An Opportunity to Work Together on the “Ultimate Cancer Prevention”

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the United States. HPV vaccination could prevent more than 90% of cancers caused by HPV. CDC recommends adolescents aged 11 to 12 get vaccinated against HPV and that everyone through age 26 get vaccinated if they haven’t yet. HPV vaccine may be given to adults age 27 through 45, based on discussions between the patient and health care provider. HPV causes about 36,000 cases of cancer in men and women every year, most commonly cervical cancer.

Each network in the Collaborative has experience working with populations with high rates of HPV-related cancers—

- The SelfMade Health Network focuses on people who have a low socioeconomic status (generally, a low income and less education).

- The Geographic Health Equity Alliance serves populations that face poor health outcomes related to where they live, work, and play.

- Nuestras Voces works with Hispanic people.

Together, the networks bring their knowledge of the problems these populations face, and resources specifically developed for them.

“We were three very different networks looking for opportunities to collaborate,” said Shonta Chambers, MSW, principal investigator for the SelfMade Health Network. “We wanted a project where we could come together as a group and support each other’s work and support states in addressing the populations that each network represents. We know that vaccination coverage is low among people experiencing poverty and we know that HPV vaccination can help prevent cervical cancer. That is why we must increase uptake of HPV vaccination.”

Nuestras Voces has also made cervical cancer prevention a priority. “Hispanic women are the most affected by cervical cancer here in the US, so it is an area of focus for us,” said Marcela Gaitán, Program Director for Nuestras Voces.

“Tobacco control advocates have always focused on big, scary, audacious goals,” said Andrew Romero, Director of the Geographic Health Equity Alliance. “We wanted to see how we could apply those learnings to other areas of cancer prevention. Could we work on HPV vaccination as ultimate cancer prevention?”

Helping States Focus on People Most in Need

The networks wanted to work with states that had shown a commitment to preventing HPV-related cancers. They were particularly interested in states that were working to improve health in the populations the networks serve. Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, and Tennessee were selected to participate in the Collaborative.

Some of the networks were already working with these states and were excited that they joined the Collaborative. “We were thrilled that Georgia was participating in this Collaborative and wanted to focus on outreach to Hispanic populations,” Ms. Gaitán said. “We had been working with them for cervical cancer prevention among Hispanic populations. Now we can build upon that work and expand our reach within the Hispanic community to provide them with accurate information for cervical cancer prevention.”

Creating Action Plans That Work

Teams from the participating states were shown examples of successful HPV vaccination plans and activities from other states. The teams were then asked to develop their own action plans. The states also had to choose the specific population they wanted to reach through the planned activities.

After reviewing the first action plans the states submitted, the networks realized that the plans were too broad. “There is always the pressure to do too much in public health,” said Mr. Romero. “We wanted the states to focus on what they were trying to achieve. What problem were they trying to address? How? What specific populations did they want to reach? What activities would help them move towards that objective?”

The networks then worked with each state team to refine their action plans. The states had to specify their goals and describe activities they would do in a specified period of time to achieve those goals.

Teams Attend Learning Sessions

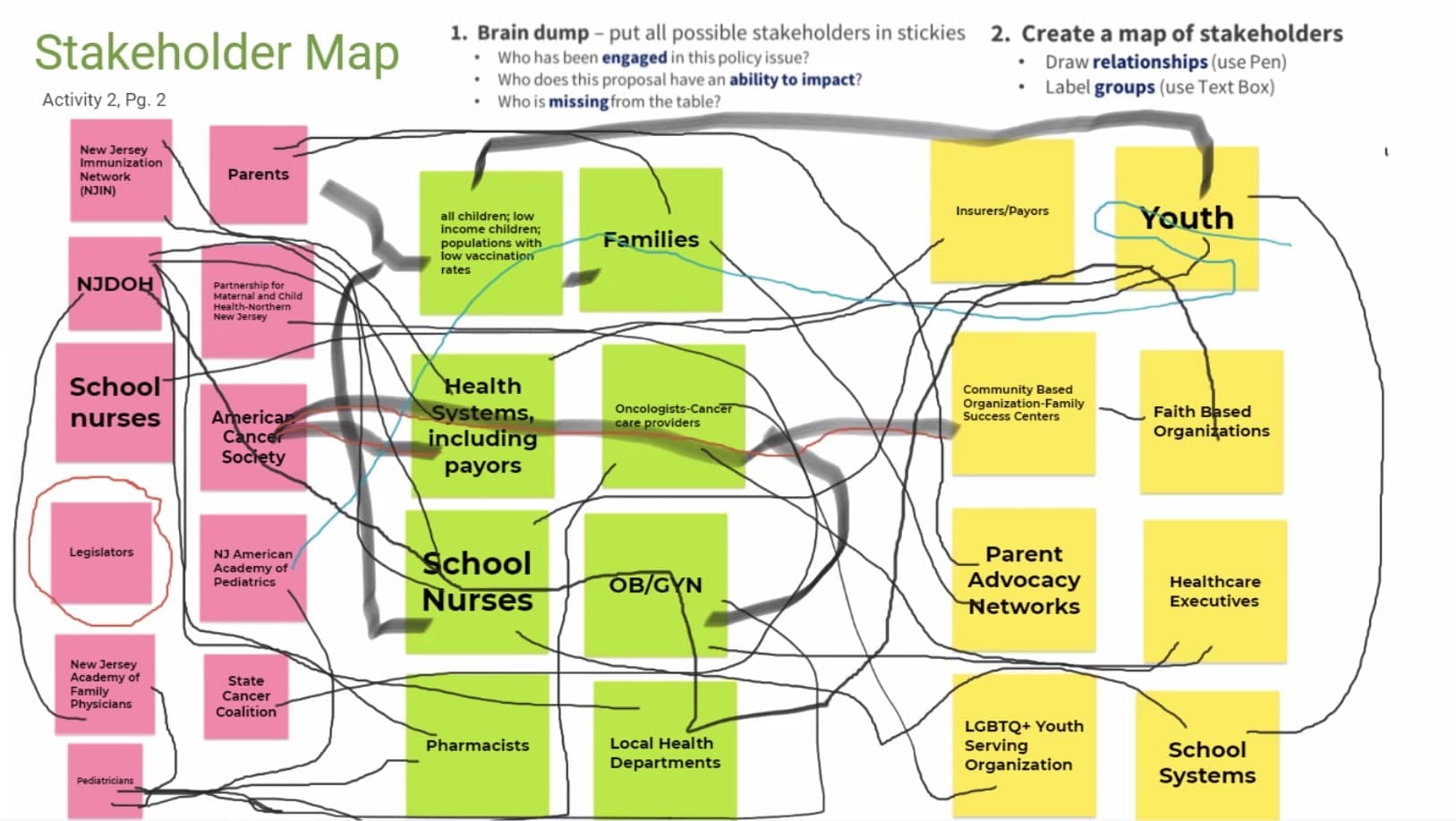

State teams created stakeholder maps during the closeout meeting in September 2020; the team from New Jersey created the map shown. A stakeholder map lists groups and organizations that can help make the changes needed or will be affected by the changes made by a public health program or policy. School system stakeholders are listed on the pink squares on the left; the green squares in the middle are health system stakeholders; and the yellow squares on the right are community stakeholders. The lines show relationships between the stakeholders.

After the action plans were revised, the networks held learning sessions about communications, program development, and policy changes. The sessions were based on the activities the states selected in their action plans. Because of the pandemic, all the sessions were held online. The learning sessions helped the state teams—

- Identify and adopt activities that have proven to improve HPV vaccination coverage among specific populations. For example, some states educate health care providers on the best ways to recommend HPV vaccines to parents.

- Explore policies that could increase HPV vaccination coverage. State teams have informed policy makers about the importance of the HPV vaccine as cancer prevention.

- Plan communication campaigns to improve knowledge about HPV vaccination. State teams have developed culturally appropriate materials to increase awareness that the HPV vaccine can prevent many cancers.

“We wanted to create a model that works through this Collaborative,” said Ms. Chambers. “To show that communities can prevent cancer more successfully when they have the right partners, plans, and solutions. We will share our learnings from this project with CDC, which can help guide states on HPV interventions in the future.”