Truck Driver and Company President Electrocuted After Crane Boom Contacts Powerline--West Virginia

FACE 93-14

SUMMARY

On March 31, 1993, a 20-year-old male truck driver (victim #1) and a 70-year-old male company president (victim #2) were electrocuted when the boom of a truck-mounted crane contacted an energized 7,200-volt conductor of a 3-phase overhead powerline while the driver was unloading concrete blocks at a residential construction site. The driver had backed the truck up the steeply sloped driveway at the residential construction site and was using the truck-mounted crane to unload a cube of concrete blocks while the company president and a masonry contractor watched. The driver, operating the crane by a hand-held remote control unit, was having difficulty unloading the cube of blocks because the truck was parked at a steep angle. While all three men watched the blocks, the tip of the crane boom contacted one of the conductors of the energized overhead powerline and completed a path to ground through the truck, the remote control unit, and the driver. The company president immediately attempted to render assistance and apparently contacted the truck, also completing a path to ground through his body. A passing motorist witnessed the incident, left the scene to summon help, and then returned to render assistance. The motorist successfully used a length of lumber to break the remote control unit tether from the crane, interrupting the path to ground through the driver. The motorist then provided first aid to the driver until relieved by local firemen and EMS personnel who responded within 16 minutes of notification. The driver was airlifted to a nearby burn center where he later died. The company president was pronounced dead at the scene.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to prevent similar occurrences, employers should:

- ensure that employees comply with the relevant standards of 29 CFR 1926.550(a)(15) for safe use of cranes proximate to overhead powerlines

- ensure that pre-work site surveys include evaluation of alternative work procedures addressing site-specific hazards

- consider retrofitting truck-mounted cranes with electrically isolated crane control systems.

INTRODUCTION

On March 31, 1993, a 20-year-old male truck driver (victim #1) and the 70-year-old male president (victim #2) of a small concrete products company were electrocuted when the boom of a truck-mounted crane contacted a 7,200-volt conductor of a 3-phase overhead powerline at a residential building site. On April 1, 1993, the county medical examiner contacted the Division of Safety Research (DSR) and requested technical assistance. On April 1, 1993, a DSR safety engineer investigated the incident at the site. The DSR representative interviewed the investigating officer from the county sheriff’s office, the plant manager for the concrete products company, the masonry contractor, and the passing motorist. The DSR representative photographed the incident site and the truck, obtained measurements of the incident site and requested the medical examiner’s report.

The employer was a concrete products company that had been in business for approximately 11 years, employing 14 workers, 3 of whom were truck drivers. Safety responsibilities were assigned to the plant manager as a collateral duty. The company had a written safety program which included general policies for truck drivers. Victim #1, the truck driver, had been driving for eight months; before that he had been employed in the company’s concrete block plant. When first assigned as a truck driver, he received training from an experienced driver, which included supervised practice unloading trucks in the plant yard. The driver was accompanied by an experienced driver on several deliveries until he was judged knowledgeable to work alone. He made his first delivery to the construction site on the day of the incident. Victim #2, the company president, had about 11 years’ experience in the concrete products industry and had been associated with the construction and mining industries during his entire working career. These were the first fatalities experienced by the company.

INVESTIGATION

The residential building site in this incident, located on a hillside, was accessed from a state road by a steeply pitched (15% grade) rough-cut driveway. The state road was 17½ feet wide and protected by a guardrail about 5 feet from the road edge opposite the entrance to the driveway. The energized overhead powerlines were located 25 feet above ground and 6 to 8 feet from the edge of the state road. Several days before the incident, the plant manager had examined the site because the company was aware of the limited operating space available for delivery trucks. The plant manager cautioned drivers, who were assigned to deliver to the site, including victim #1, about the limited space available for parking delivery trucks, the steep grade of the driveway, and the proximity to the overhead powerlines.

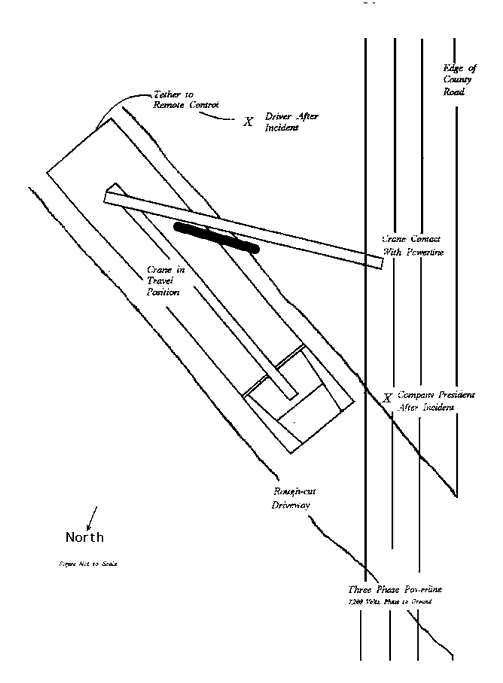

On the day of the incident, the company president arrived at the site shortly after 2:30 p.m. to meet with the masonry contractor and to observe the delivery. The driver, who had been dispatched to the site at 2:15 p.m. with 28,490 pounds of concrete blocks, arrived at about 2:45 p.m. The driver, directed into the driveway by the company president, backed the truck up the driveway until the rear wheels reached the upper end. He set the crane outriggers, positioned himself 20 to 30 feet from the truck’s left side, and operated the crane by the tethered remote control unit. The company president and the masonry contractor walked to the rear of the truck to watch the driver unload the blocks. Because the truck was parked on the steeply sloped drive, when the driver lifted the first cube of blocks (i.e., a quantity of concrete blocks stacked so that they can be readily removed from the truck by the crane), it swung forward against an adjacent cube. The driver had difficulty maneuvering the cube of blocks away from the truck bed because the truck was parked at an angle on the steep slope causing the cube to contact an adjacent cube. The driver, the company president, and the masonry contractor were focusing their attention on the cube of blocks. While the driver attempted to unload the cube, the masonry contractor saw a ball of fire travel down the remote control tether and ignite the driver’s clothing in his chest area. As the driver fell backward in flames, the masonry contractor saw the company president run to the driver’s assistance. Approaching the driver, the company president slid down the steep bank then climbed to his feet and ran toward the open door of the truck cab (Figure). Because the masonry contractor was standing behind the truck, he did not see the company president contact the truck.

During the incident, a motorist driving on the state road, approached the site and saw arcing between the powerlines and the crane boom. According to the motorist, he stopped his car some distance from the site, waited until the arcing stopped, then drove by the site. As he drove by, the masonry contractor called to him to summon help. The motorist drove to a nearby office and asked the workers to call 911 for emergency help. He then returned to the site where he simultaneously noticed a small fire at the rear of the truck, the driver about 20 feet away from the truck holding the remote control unit, and the masonry contractor shoveling dirt on the fire. He stopped his vehicle and called to both men to abandon the area. At that instant, another arc occurred between the crane boom and the 7,200-volt powerline and the motorist saw flame travel down through the tether to the driver. The grass and brush around the driver caught fire, and the motorist called again to the masonry contractor to leave the area. The motorist then climbed the bank towards the truck. Picking up a length of 2 by 4 lumber, he approached the truck from uphill until he was close enough to break the remote control tether connection to the crane with the 2 by 4 board. While the masonry contractor shoveled dirt on the fire, the motorist picked up a water hose used at the site and doused the fire. Once the fire was extinguished, the motorist went to the driver, who was on the ground gasping for air. The local fire department arrived within 16 minutes of being notified and took charge of the scene, followed shortly by the EMS. The driver was airlifted from the site to a burn center approximately 70 miles away where he later died. The company president was pronounced dead at the scene.

The masonry contractor stated during interviews that when he first observed the flame traveling along the tether, he thought the truck’s electrical system had malfunctioned. He last observed the company president running toward the open door of the truck cab, but because the company president was out of his line of sight, the masonry contractor did not see him contact the truck.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The medical examiner’s office determined the cause of death for the company president as electrocution. The driver died as a result of 98% total body burns, third degree electrical.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation No. 1: Employers should ensure that employees comply with the relevant standards of 29 CFR 1926.550(a)(15) for safe use of cranes proximate to overhead powerlines.

Discussion: Of particular importance in this incident are the provisions of 29 CFR 550(a)(15)(i) which require that for power lines rated at 50 kV or less, 10 feet of clearance be maintained between the lines and the equipment and any part of the load. Additionally, 29 CFR 550(a)(15)(iv) requires that a person be designated to observe the clearance between the lines and the equipment, and to give timely warning for all operations where it is difficult for the operator to maintain desired clearance by visual means. The powerline in this incident, part of a 3-phase distribution system of 7,200-volts phase to ground, ran parallel to the county road with the center conductor 6 to 8 feet from the road’s edge and 25 feet above ground level. During the incident the crane boom contacted the field (or site side) conductor which was located 10 to 12 feet from the road edge. The truck boom was 10½ feet above ground level when in the transport position, and accounting for the 15% grade on which the truck was parked, would have been about 12 to 14 feet below and about 6 feet away from the field side conductor before being elevated to unload the cube of blocks (Figure). To unload the blocks, the crane had to be raised out of its cradle and swung to the side, placing it under the field conductor and eliminating safe clearance between the crane boom and the energized conductor. The driver experienced difficulty unloading the blocks, and had to divide his attention on the clearance between the lines and the boom, and the movement of the cube of blocks, which was taking place in another direction and at a lower elevation. Designating a person to monitor the clearance between the boom and the energized lines, and to give timely warnings, provides equipment operators with additional assistance in maintaining safe line clearances.

Recommendation No. 2: Employers should ensure that pre-work site surveys include evaluation of alternative work procedures addressing site-specific hazards.

Discussion: Several days before the incident, a worksite survey was conducted which revealed several potential hazards that might affect the safe delivery of the building materials. All drivers assigned to deliver to the site had been cautioned about the hazards. Such pre-work site surveys can also include evaluation of work procedures other than delivering the materials directly to the site. One alternative might have been to unload the materials at another location and transfer them to a smaller vehicle for delivery to the site. Although such an operation may have been more labor intensive and time consuming than direct delivery using the truck-mounted crane, use of a smaller vehicle at the site could have provided additional space for maintenance of safe clearance between the unloading operation and the energized powerlines. Another alternative could have been to request the utility company to de-energize or insulate the overhead powerlines. De-energization and visible grounding of the powerlines would eliminate the source of hazardous energy. Where it is not possible or desirable to interrupt power transmission, overhead lines could be temporarily insulated to provide additional protection during crane use. While temporary insulation of powerlines using line hose or blankets cannot be viewed as an alternative to maintaining safe clearance, such insulation could provide redundant protection when energized powerlines are inadvertently contacted during difficult maneuvering of crane booms and loads.

Recommendation No. 3: Employers should consider retrofitting truck-mounted cranes with electrically isolated crane control systems.

Discussion: The remote control unit used on the crane was electrically connected to the crane. This unit provided a path to ground when held by the driver. A system which is isolated electrically could protect the crane operator in the event of inadvertent contact with energized electrical conductors. Such a system might employ the use of radio or fiber optics to transmit control signals, eliminating the path to ground through electrical conductors.

REFERENCE

29 CFR 1926.550(15) Code of Federal Regulations, U.S. Government Printing Office, Office of Federal Register, page 204, July 1, 1990.

Figure. Location of Truck Relative to Powerline