Partnerships and Community Engagement Key to Policy, Systems, and Environmental Achievements for Healthy Eating and Active Living: a Systematic Mapping Review

CME ACTIVITY — Volume 19 — August 25, 2022

Leslie Cunningham-Sabo, PhD, RDN1,2; Angela Tagtow, MS, RD, LD3; Sirui Mi, MA, MS, RDN1; Jessa Engelken, MPH, RDN, LD4; Kiaya Johnston1; Dena R Herman, PhD, MPH, RD5,6 (View author affiliations)

Suggested citation for this article: Cunningham-Sabo L, Tagtow A, Mi S, Engelken J, Johnston K, Herman DR. Partnerships and Community Engagement Key to Policy, Systems, and Environmental Achievements for Healthy Eating and Active Living: a Systematic Mapping Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2022;19:210466. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210466.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and Preventing Chronic Disease. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 1.0 MOC points in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. Participants will earn MOC points equivalent to the amount of CME credits claimed for the activity. It is the CME activity provider’s responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit.

Release date: August 25, 2022; Expiration date: August 25, 2023

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

- Distinguish characteristics of research into healthy living

- Assess actions in healthy living research

- Analyze the most successful components of healthy living research

- Evaluate lessons learned from healthy living research

EDITOR

Rosemarie Perrin

Editor

Preventing Chronic Disease

Atlanta, GA

CME AUTHOR

Charles P. Vega, MD

Health Sciences Clinical Professor of Family Medicine

University of California, Irvine School of Medicine

Irvine, California

Charles P. Vega, MD, has the following relevant financial relationships:

Advisor or consultant for: GlaxoSmithKline; Johnson & JohnsonAUTHORS

AUTHORS

Leslie Cunningham-Sabo, PhD, RDN

Colorado State University, Food Science and Human Nutrition; Colorado School of Public Health, Community and Behavioral Health, Fort Collins, CO

Angie Tagtow, MS, RD, LD

Äkta Strategies, LLC, Elkhart, IA

Sirui Mi, MS, RDN

Colorado State University, Food Science and Human Nutrition, Fort Collins, Colorado

Jessa Engelken, MPH, RDN

University of Washington Seattle Campus, Public Health, Seattle, Washington

Kiaya Johnston

Colorado State University, Food Science and Human, Nutrition, Fort Collins, Colorado

Dena Herman, PhD, MPH, RD

University of California Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health; California State University Northridge, Nutrition, Los Angeles, California, and Northridge, California

PEER REVIEWED

What is already known on this topic?

Policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) change approaches are frequently used for healthy eating and active living (HEAL) initiatives. Results are often difficult to determine, however, because of their multicomponent designs and insufficient evaluation.

What is added by this report?

We used the Individual + PSE Conceptual Framework for Action to map HEAL initiatives and related evaluation efforts. Evaluation gaps were prevalent for assessing the strength of community and partnership engagement.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Frameworks that plan for and evaluate community engagement and partnerships, such as I+PSE, can support achievement of initiative goals.

Abstract

Introduction

Policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) change approaches frequently address healthy eating and active living (HEAL) priorities. However, the health effects of PSE HEAL initiatives are not well known because of their design complexity and short duration. Planning and evaluation frameworks can guide PSE activities to generate collective impact. We applied a systematic mapping review to the Individual plus PSE Conceptual Framework for Action (I+PSE) to describe characteristics, achievements, challenges, and evaluation strategies of PSE HEAL initiatives.

Methods

We identified peer-reviewed articles published from January 2009 through January 2021 by using CINAHL, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CAB Abstracts databases. Articles describing implementation and results of PSE HEAL initiatives were included. Activities were mapped against I+PSE components to identify gaps in evaluation efforts.

Results

Independent reviewers examined 437 titles and abstracts; 52 peer-reviewed articles met all inclusion criteria. Twenty-four focused on healthy eating, 5 on active living, and 23 on HEAL. Descriptive analyses identified federal funding of initiatives (typically 1–3 years), multisector settings, and mixed-methods evaluation strategies as dominant characteristics. Only 11 articles reported on initiatives that used a formal planning and evaluation framework. Achievements focused on partnership development, individual behavior, environmental or policy changes, and provision of technical assistance. Challenges included lack of local coalition and community engagement in initiatives and evaluation activities and insufficient time and resources to accomplish objectives. The review team noted vague or absent descriptions of evaluation activities, resulting in questionable characterizations of processes and outcomes. Although formation of partnerships was the most commonly reported accomplishment, I+PSE mapping revealed a lack of engagement assessment and its contributions toward initiative impact.

Conclusion

PSE HEAL initiatives reported successes in multiple areas but also challenges related to partnership engagement and community buy-in. These 2 areas are essential for the success of PSE HEAL initiatives and need to be adequately evaluated so improvements can be made.

Introduction

Obesity prevention and other public health initiatives emphasize policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) change in addition to traditional approaches that focus on individuals (1,2). Federal PSE initiatives include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) State Physical Activity and Nutrition Program, High Obesity Program, and Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health program and the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) and Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP).

Evidence is lacking for the health impact of PSE initiatives because of their complex nature, insufficient capacity and resources for program implementation (3,4), and absence of robust evaluation strategies (5). Several theory-based models and frameworks have informed PSE initiatives, including the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) model (6), a systems thinking framework (7), a collective impact framework (8), a policy adoption model (2), and SNAP-Ed (9), along with an emphasis on health equity (10,11). A new framework is the Individual Plus Policy, Systems, and Environmental Conceptual Framework for Action (I+PSE) (12), informed by CDC’s Social–Ecological Model (13) and the Contra Costa Health Services Spectrum of Prevention (14). I+PSE is unique in that it views determinants of health through social, commercial, and political lenses. It guides users to examine a range of tactics to produce sustainable and synergistic effects through 7 action components (Table 1).

- Strengthen individual knowledge and skills

- Promote community engagement and education

- Activate intermediaries and service providers

- Facilitate partnerships and multisector collaborations

- Align organizational policies and practices

- Foster physical, natural, and social settings

- Advance public policy and legislation

I+PSE then addresses the necessity of complex evaluation strategies at multiple levels to identify outcomes and effects intended by these coordinated action components. The cyclical processes of assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation are supported by systems thinking and reflection.

Our review characterizes activities implemented and evaluated in PSE HEAL (healthy eating and active living) initiatives by using I+PSE’s 7 action components to answer 5 questions:

- What are the key characteristics of PSE HEAL initiatives?

- How are the 7 I+PSE components represented in these initiatives?

- How are achievements and challenges described?

- How are initiative activities evaluated?

- Are there gaps in evaluation, and if so, where?

Methods

Data sources

We chose a systematic mapping review approach because of its relevance for addressing our research questions. Mapping reviews categorize and map existing literature and are based on questions rather than topics (15,16). This type of review is the most appropriate design for assessing an abundance of diverse research. Such reviews can identify gaps in the area of interest and can act as a first step toward a traditional systematic review (17).

Criteria for articles included in our review were that they were published in English from January 2009 through January 2021, reported the implementation and evaluation of a HEAL initiative, and discussed PSE activities. Conference abstracts, reviews, and commentaries were excluded. We used Mendeley Reference Manager software, version 1.19.8 (Mendeley Ltd) for storage and sorting of retrieved documents and followed the criteria outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (18).

After consultation with a research librarian, authors completed the literature search by using these terms: “policy, systems, and environmental” OR “policy, systems, and environment” OR “policy, systems, environment” OR “policy, systems, environmental” OR “policy and environmental” AND evaluat* OR assess* OR initiative OR intervention OR framework. We searched CINAHL, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CAB Abstracts databases. An initial search was conducted in January 2020, and results were updated with a search in January 2021 following the same procedures.

Study selection

After removing duplicate records, we reviewed search results in 3 phases. In the first phase, 1 researcher reviewed each record’s title and abstract. Records passed this phase if they contained any mention of PSE and dealt with a topic related to public health. All remaining documents were sorted into either “pass” or “fail” electronic folders.

In the second phase, the same researcher completed a more detailed review of the title and abstract records that passed the first review phase. During this step, articles were divided into 7 folders: 1) those eligible for full text review because their primary focus was PSE and HEAL, 2) those that did not specifically deal with PSE and HEAL, 3) those that described a PSE HEAL initiative’s protocol or methods but no intervention results, 4) those that discussed a PSE evaluation framework that did not include application to a specific initiative, 5) conference abstracts, 6) reviews, and 7) commentaries. Meetings between the lead author and research coder confirmed appropriate sorting of the initial 20 articles and operational definitions for the 7 I+PSE components. Notes were written in the Mendeley annotations function for each article that was related to PSE and HEAL, providing the rationale for their folder assignment.

For the final review phase, 2 researchers were trained to independently examine the full text of articles describing PSE HEAL initiatives to determine if they included implementation and evaluation activities for any of the 7 I+PSE components. This training consisted of 2 coders and the lead researcher (L.C.S.) reviewing and coding the same 5 articles individually and then comparing their results. If any disagreements were noted, activities and components were discussed to determine final categorization. No reliability testing was done. For the remainder of the articles, coders noted any description of the 7 I+PSE components, whether or not specific activities were evaluated, and what evaluation frameworks and methods, if any, were used. Over several meetings, the 2 coders reviewed their coding for each article and reached consensus for either inclusion or exclusion. In instances of uncertainty, they consulted the lead researcher for a final decision. Additional notes were made to provide the rationale for these decisions.

Data extraction

One coder extracted and entered data into a results table (Table 2). A second coder compared the articles’ content with table entries to confirm the accuracy of all content. The lead author reviewed all table content for consistency of descriptions. This table included the last name of the first author and publication date, funder(s) of the research described in the article, name and purpose of the initiative, study setting, and length of study. The table also indicated which of the 7 components of I+PSE were addressed in intervention activities, which were evaluated and how, accomplishments and challenges noted by the article authors, and comments from our coders on the extent of evaluations. This approach is an appropriate strategy for mapping reviews, rather than applying a more formal quality assessment tool (eg, Cochrane) (17). We used quantitative counts and qualitative content analysis strategies to summarize data and reveal themes as recommended by Miles et al (73). Themes from each column (eg, funding source, I+PSE components described) were inductively determined by first reviewing the content and subsequently creating categories. The same 2 researchers who entered and confirmed these data and the lead researcher determined the themes and categories together over several meetings. Counts were then generated for each category and summarized in narrative, table, or figure format. We did not attempt a meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of initiatives and measured outcomes.

Results

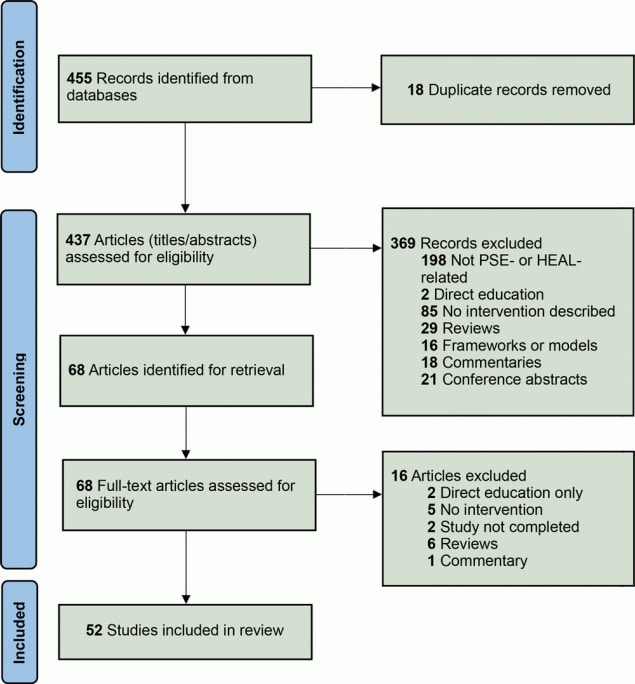

We developed a PRISMA flowchart (18) (Figure 1) noting reasons for inclusion and exclusion of articles through our 3-step review. We identified 455 articles and removed 18 duplicates. Of the remaining 437, most (n = 369) were removed because they were not PSE- or HEAL-related or because they did not describe an intervention. For articles undergoing full-text review, 16 were excluded because they described direct education, did not describe an intervention, the study was not complete, or the articles were reviews or commentaries. Of these, 52 initiatives met all inclusion criteria: 24 focused solely on healthy eating, 5 on active living, and the remaining 23 on a combination of both.

![]()

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram for identification of 52 studies included in a systematic mapping review of initiatives dealing primarily with policy, systems, and environmental achievements for healthy eating and active living. [A text version of this figure is available.]

Initiative characteristics

The most common funding sources for selected studies were federal government agencies, with CDC (n = 23), the National Institutes of Health (n = 8), and USDA (n = 7) the most prominent (Table 2). Other funding sources included foundations (n = 12) and state governments (n = 5). Some initiatives received funding from several sources. Only 2 of the 52 initiatives, both in Australia, were from researchers outside the US. Often initiatives took place in multiple settings, the most common being schools, businesses, and community organizations (Table 3). Some studied specific groups, such as people with incomes below the federal poverty level or people with high rates of obesity, and some studied racial or ethnic communities. Most initiatives (73%) were funded for 1 to 3 years.

Methods for evaluating interventions included surveys, interviews, observations, photographs, and document reviews. Seven initiatives used only surveys, 2 used only individual or group interviews, and 6 used only reviews of documents such as reports, action plans, and meeting minutes. Most (n = 34) interventions used a mixed-methods approach, and 3 reported no evaluation activities at all. Only 11 of the 52 initiatives reported using a planning or evaluation framework, 3 of which used Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) (19,32,46). All other frameworks mentioned were used for a single initiative (20,29,31,36,38,39,62,72).

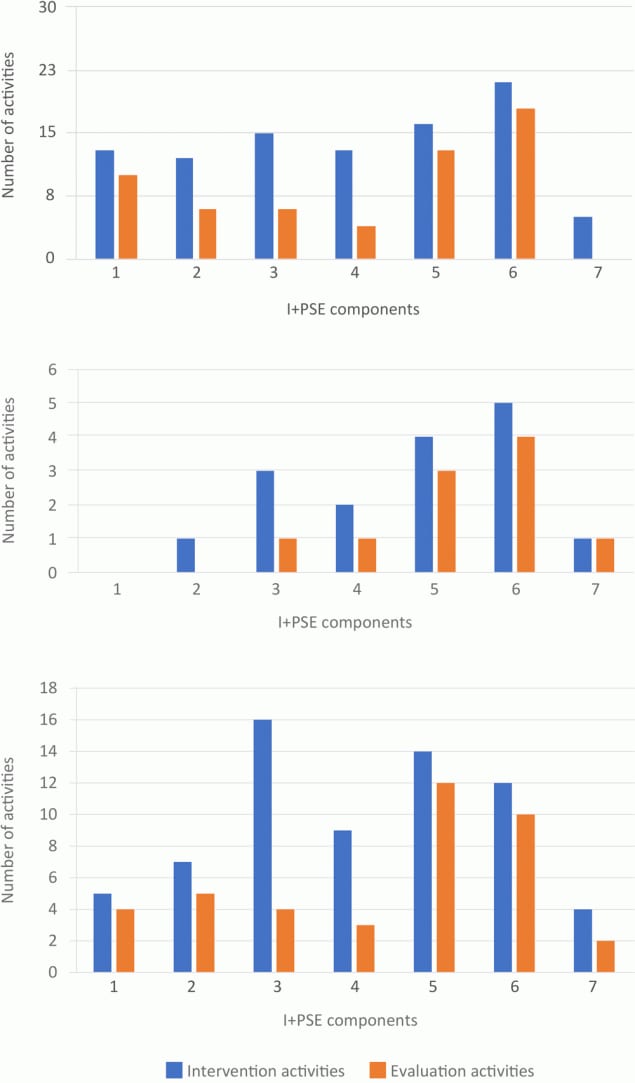

We organized HEAL interventions’ implementation and evaluation activities by the 7 I+PSE components (Figure 2). Healthy eating (n = 24) (19,22,28–30,32,34,35,38,39,43,44,46–48,52,53,56,59–62,64,66,68,71) and HEAL (n = 23) (1,20,21,24,26,27,33,36,37,40–42,45,49–51,54,57,58,63,65,67,69,72) initiatives included many intervention and evaluation activities across the 7 I+PSE components, with an emphasis on activities addressing organizational policy (I+PSE component 5) and environmental changes (I+PSE component 6) as anticipated because of the nature of this review. Those that only focused on active living (n = 5) (23,25,31,55,70) also emphasized activities addressing organizational policy (I+PSE component 5) and environmental changes (I+PSE component 6), to the near exclusion of all other components. Only 12 interventions of any kind reported attempting to advance public policies and legislative activities (I+PSE component 7) (20,26–28,31,32,49,50,54,56,59,65,71). Interestingly for PSE-focused initiatives, 20 included activities directed at the individual behavior change level (I+PSE component 1) (24,26,27,34,35,38,39,41–44,46,47,53,56,58,59,61,62,68,69,71,72). Of the 7 I+PSE components, the least likely to include evaluation activities were to “promote community engagement and education” (I+PSE component 2, 55%), “educate intermediaries and service providers” (I+PSE component 3, 32%), “facilitate partnerships and multisector collaborations” (I+PSE component 4, 33%), and “advance public policies and legislation” (I+PSE component 7, 30%).

![]()

Figure 2.

Number of activities described in 52 studies of PSE HEAL (policy, systems, and environmental healthy eating and active living) initiatives, sorted by the 7 components of the Individual Plus Policy, System, and Environmental Conceptual Framework for Action (I+PSE) (12): 1) strengthen individual knowledge and behavior, 2) promote community engagement and education, 3) educate intermediaries and service providers, 4) facilitate partnerships and multisector collaborations, 5) align organizational policies and practices, 6) sustain physical, natural and social settings, and 7) advance public policies and legislation. Graph A describes healthy eating initiatives (n = 24), B describes active living initiatives (n = 5), and C describes combined healthy eating and active living initiatives (n = 24). Initiatives may include multiple activities. [A tabular version of this figure is available.]

From the qualitative portion of the content analysis, we summarized each article’s description of accomplishments and challenges (Table 2). Initiative accomplishments were (in descending order of frequency) partnerships formed, individual behavior change, environmental and policy changes, and provision of technical assistance. Challenges were almost exclusively insufficient early engagement or investment of participating communities, resulting in resistance to initiative implementation (20,34,35,46,48,67,72). Another common challenge noted was insufficient or variable implementation because of limited resources and time and staff turnover (41,45,46,49,50,54,57,66). Lessons learned, culled from the descriptions of both accomplishments and challenges, included the importance of recruiting staff who had local trust and connections (19,33) and the value of early achievements to promote community buy-in (34,35,45,72). Authors also reported variability in the extent of implementation between different sizes of sites (36,51,57), although there was no consistent finding that larger (or smaller) sites had stronger implementation. They also reported variability on extent of implementation because of the perceived strength of collaborative partnerships, most often informally assessed through interviews or surveys (23,34–36,50,51,57,60,72).

Evaluation limitations were noted in some articles by authors and throughout our systematic coding process. As with resistance to participation in initiative activities, some authors identified reluctance of participants and stakeholders to engage in evaluation activities because of response burden and lack of buy-in (23,26–28,34,35,38,46). For many initiatives, we authors and/or other members of our review team noted limitations of evaluation tools used in terms of imprecision and insufficient coverage of intervention activities (22,33,40–42,45–52,54,55,57,58,63,65,69). Another limitation to assessing the impact of these PSE interventions was the lack of baseline or long-term follow-up measures (30,32,34,35,46,49,52,53,68). A recurring theme identified from our content analysis was the vague and limited description of evaluation tools and strategies (22,33,40–42,45–52,54,55,58,59,63,65,69).

Discussion

Our review of 52 PSE HEAL initiatives describes their key characteristics and maps the I+PSE action components most commonly included in the intervention-to-evaluation activities. It also characterizes these initiatives’ achievements, challenges, and lessons learned. The review concludes by summarizing the evaluation matches and missed opportunities to strengthen the evidence for their outcomes.

Our review showed a gap between the most frequently reported achievement — forming partnerships — and the absence of assessments of the quality and impact of these partnerships. As the articles we reviewed stated repeatedly, weak engagement at both the coalition and community levels limited opportunities to achieve anticipated PSE Framework outcomes. Because the activities intended to foster such engagements were the least often evaluated, the influence and impact of these activities were largely unknown. Only 2 articles (49,55) mentioned measuring the quality of partnerships, but both described the use of surveys vaguely. Although the formation of coalitions and community relationships are an expected step in PSE work, the emphasis is often on documenting program implementation and outcomes. Asada and colleagues (5) concluded from their review of public health interventions that the use of valid and available evaluation tools would strengthen what we know about the impact of structural change initiatives. These include tools that measure partner engagement and collaboration. Measurement resources exist: Kegler and Swan (74) developed the Community Coalition Action Theory, which links participant engagement and resources to change community outcomes, including policy achievement. One research-tested tool to assess the effectiveness of collaborations is the Collaboration Factors Inventory offered by the Wilder Organization (75), which includes 22 success factors. Another tool is the Collaboration Framework developed by the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Service, which characterizes the degree of collaboration based on a depth-of-relationship integration scale (76). I+PSE initiative leaders would do well to employ such partnership assessment tools to determine the quality and impact of their interventions.

A related finding was the lack of planning and evaluation frameworks. Brennan and colleagues (77) reviewed childhood obesity policy and environmental initiatives using the RE-AIM Framework and concluded that it was difficult to describe and summarize initiative outcomes because they lacked formal evaluations, and their multicomponent nature made it difficult to attribute outcomes to specific activities. In a scoping review of structural public health interventions, Asada and colleagues (5) reported insufficient application of theory-based evaluation frameworks and validated tools to measure change at the environmental level. Our mapping review also noted absence of planning and evaluation frameworks for all but 11 of the 52 initiatives reviewed (19,20,29,31,32,36,38,39,46,62,72). I+PSE was applied in this review because of its theoretical underpinnings, its acknowledgment and examination of the multidimensional components that support PSE change, and its adaptability to categorize HEAL initiatives. Frameworks that include assessment, engagement, and formation and strategies to strengthen coalitions and community involvement, such as I+PSE, will support the effectiveness of PSE initiatives.

We also found the limited funding period of just 1 to 3 years required by government and foundation funding sources to be disappointing but not unexpected. The time needed to establish or strengthen existing coalitions, assess needs, and prioritize PSE strategies can be lengthy but is essential for success (45,78). For example, after examining efforts to improve maternal and child health outcomes in 14 North Carolina counties, Schaffer and colleagues (8) concluded that more upfront time was necessary to form community action teams able to sustain community engagement. After Holston and colleagues (45) implemented multilevel obesity prevention interventions in 3 rural Louisiana parishes, they recommended identifying attainable early successes, not only to engage and strengthen partnerships but also in recognition of the time it takes for significant PSE change to be realized. When funding periods cannot be lengthened, funders, researchers and practitioners must identify realistic outcomes for these brief timeframes, such as the development of strong community linkages.

The need for technical assistance for I+PSE implementation and evaluation has been widely reported (2), including by those using the SNAP-Ed Evaluation Framework (79–81). Naja-Riese and colleagues (9) noted in their review of national SNAP-Ed results that implementing agencies still focused most of their activities and evaluation measures at the traditional individual-change level, despite the intended focus on PSE change. They posited that practitioners need technical assistance to learn to implement and measure multisector activities. Our review found similarly that delivery of individual behavior change activities was the second most frequent accomplishment. Herman and colleagues (82) noted from interviews with state and regional public health nutrition teams working in maternal and child health the need for technical assistance and the value it garnered in the development of PSE action plans. In our review, 7 initiatives provided technical assistance to coalition members leading PSE efforts or intermediary service providers (28,45,46,48,54,64,70), but none described in any detail recipient response to the value or effectiveness of the technical assistance. Assessing and addressing I+PSE implementation and evaluation capacity and readiness for teams leading the initiative is critical for success but was not even described in any of the 52 articles we reviewed.

Using a mapping review approach allowed us to visualize the match between intervention and evaluation activities across the 7 distinct components of I+PSE. Ours is the first attempt, to our knowledge, to examine and characterize PSE HEAL initiatives with the detail this I+PSE provides and with an evaluation focus. We found the framework to be adaptable and applicable to a variety of HEAL initiatives, and unlike other frameworks, it acknowledges and includes assessment of individual behavior change resulting from PSE approaches, which are common activities in PSE initiatives.

However, our review was not exhaustive. We did not seek out articles related to those in our review that did not meet the inclusion criteria themselves, nor did we search the gray literature. We also did not report funding amounts, which could have influenced the scope and reach of these initiatives, including their evaluation activities and results. Funding amounts would be an important component in future reviews, as would a more in-depth examination of the relationships between strength of coalition and community engagement and achievement of PSE outcomes. Future reviews also could explore the perceived value and application of evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence (83) in PSE HEAL initiatives for which there is no “best” intervention and evaluation design because of diversity in aims and approaches, and multicomponent complexity (5). Future research also could examine funding sources, I+PSE activities and evaluation components, and outcomes for different audiences (eg, by school level, initiative setting) to identify patterns specific to those audiences. Finally, despite the breadth of our search terms, only 2 initiatives were identified outside the US (48,83), and both of these were located in Australia. This limits the generalizability of our results.

As poor dietary patterns, sedentary lifestyles, diet-related chronic diseases, and associated health care costs increase in the US (84), the need is urgent for greater focus on and investment in learning how individual PSE change approaches can be optimized to advance healthy eating and active living across households, communities, and populations. Our mapping review shows potential gaps and suggests opportunities to advance research and practice in formulating, implementing, and evaluating PSE HEAL initiatives. Future initiatives should give special attention to closing the gap between activating community and service provider partnerships and evaluating the quality and impact of these relationships, because outcomes will rely on the strength of these relationships.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported in part by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. We acknowledge the guidance of research librarian Sadie Skeels for her consultation on designing terms for the literature search, Chelsea Didinger for her assistance in planning and conducting the initial search, and Kaitlyn Havenner and Michaela Harvey for assisting with manuscript formatting. No copyrighted material was used in this article.

Author Information

Corresponding Author: Leslie Cunningham-Sabo, PhD, RDN, Colorado State University, Food Science and Human Nutrition, 1571 Campus Delivery, 234 Gifford Building, Fort Collins, CO 80523. Telephone: (970) 980-5984. Email: Leslie.Cunningham-Sabo@Colostate.Edu.

Author Affiliations: 1Colorado State University, Food Science and Human Nutrition, Fort Collins, Colorado. 2Colorado School of Public Health, Community and Behavioral Health, Aurora, Colorado. 3Äkta Strategies, LLC, Elkhart, Iowa. 4University of Washington, School of Public Health, Nutritional Sciences Program, Seattle, Washington. 5University of California Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, California. 6California State University Northridge, Nutrition, Dietetics, and Food Science, Northridge, California.

References

- Bunnell R, O’Neil D, Soler R, Payne R, Giles WH, Collins J, et al. ; Communities Putting Prevention to Work Program Group. Fifty communities putting prevention to work: accelerating chronic disease prevention through policy, systems and environmental change. J Community Health 2012;37(5):1081–90. CrossRef PubMed

- Walter L, Dumke K, Oliva A, Caesar E, Phillips Z, Lehman N, et al. From tobacco to obesity prevention policies: a framework for implementing community-driven policy change. Health Promot Pract 2018;19(6):856–62. CrossRef PubMed

- El-Kour TY, Kelley K, Bruening M, Robson S, Vogelzang J, Yang J, et al. Dietetic workforce capacity assessment for public health nutrition and community nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet 2021;121(7):1379–1391.e21. CrossRef PubMed

- Draper CL, Younginer N. Readiness of Snap-Ed implementers to incorporate policy, systems, and environmental approaches into programming. J Nutr Educ Behav 2021;53(9):751–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Asada Y, Lieberman LD, Neubauer LC, Hanneke R, Fagen MC. Evaluating structural change approaches to health promotion: an exploratory scoping review of a decade of U.S. progress. Health Educ Behav 2018;45(2):153–66. CrossRef PubMed

- Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res 2006;21(5):688–94. CrossRef PubMed

- Brennan LK, Sabounchi NS, Kemner AL, Hovmand P. Systems thinking in 49 communities related to healthy eating, active living, and childhood obesity. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015;21(Suppl 3):S55–69. CrossRef PubMed

- Schaffer K, Cilenti D, Urlaub DM, Magee EP, Owens Shuler T, Henderson C, et al. Using a collective impact framework to implement evidence-based strategies for improving maternal and child health outcomes. Health Promot Pract 2021;1524839921998806. CrossRef PubMed

- Naja-Riese A, Keller KJM, Bruno P, Foerster SB, Puma J, Whetstone L, et al. The SNAP-Ed Evaluation Framework: demonstrating the impact of a national framework for obesity prevention in low-income populations. Transl Behav Med 2019;9(5):970–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Kumanyika SK. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. Am J Public Health 2019;109(10):1350–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Reis-Reilly H, Fuller-Sankofa N, Tibbs C. Breastfeeding in the community: addressing disparities through policy, systems, and environmental changes interventions. J Hum Lact 2018;34(2):262–71. CrossRef PubMed

- Tagtow A, Herman DR, Cunningham-Sabo L. Next-generation solutions to address adaptive challenges in dietetics practice: the I+PSE Conceptual Framework for Action. J Acad Nutr Diet 2022;122(1):15–24. CrossRef PubMed

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist 1977;32(7):513–31. CrossRef

- Cohen L, Swift S. The spectrum of prevention: developing a comprehensive approach to injury prevention. Inj Prev 1999;5(3):203–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Welcome to the EPPE-Centre. EPPI. Published January 1, 2021. Accessed August 15, 2021. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms

- Cooper ID. What is a “mapping study?” J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104(1):76–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26(2):91–108. CrossRef PubMed

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. CrossRef PubMed

- Abildso CG, Bias TK, Coffman J. Adoption and reach of a statewide policy, systems, and environment intervention to increase access to fresh fruits and vegetables in West Virginia. Transl Behav Med 2019;9(5):847–56. CrossRef PubMed

- Agner J, Pirkle CM, Irvin L, Maddock JE, Buchthal OV, Yamauchi J, et al. The Healthy Hawai’i Initiative: insights from two decades of building a culture of health in a multicultural state. BMC Public Health 2020;20(1):141. CrossRef PubMed

- Arriola KRJ, Hermstad A, Flemming SSC, Honeycutt S, Carvalho ML, Cherry ST, et al. Promoting policy and environmental change in faith-based organizations: description and findings from a mini-grants program. Am J Health Promot 2017;31(3):192–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Askelson NM, Brady P, Ryan G, Meier C, Ortiz C, Scheidel C, et al. Actively involving middle school students in the implementation of a pilot of a behavioral economics-based lunchroom intervention in rural schools. Health Promot Pract 2019;20(5):675–83. CrossRef PubMed

- Balis LE, Strayer T 3d. Evaluating “Take the Stairs, Wyoming!” through the RE-AIM framework: challenges and opportunities. Front Public Health 2019;7:368. CrossRef PubMed

- Berman M, Bozsik F, Shook RP, Meissen-Sebelius E, Markenson D, Summar S, et al. Evaluation of the Healthy Lifestyles Initiative for improving community capacity for childhood obesity prevention. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:E24. CrossRef PubMed

- Castillo EC, Campos-Bowers M, Ory MG. Expanding bicycle infrastructure to promote physical activity in Hidalgo County, Texas. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E126. CrossRef PubMed

- Cheadle A, Schwartz PM, Rauzon S, Beery WL, Gee S, Solomon L. The Kaiser Permanente Community Health Initiative: overview and evaluation design. Am J Public Health 2010;100(11):2111–3. CrossRef PubMed

- Cheadle A, Rauzon S, Spring R, Schwartz PM, Gee S, Gonzalez E, et al. Kaiser Permanente’s Community Health Initiative in Northern California: evaluation findings and lessons learned. Am J Health Promot 2012;27(2):e59–68. CrossRef PubMed

- Cheadle A, Cromp D, Krieger JW, Chan N, McNees M, Ross-Viles S, et al. Promoting policy, systems, and environment change to prevent chronic disease: lessons learned from the King County Communities Putting Prevention to Work initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract 2016;22(4):348–59. CrossRef PubMed

- Coleman KJ, Shordon M, Caparosa SL, Pomichowski ME, Dzewaltowski DA. The healthy options for nutrition environments in schools (Healthy ONES) group randomized trial: using implementation models to change nutrition policy and environments in low income schools. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012;9(1):80. CrossRef PubMed

- Cranney L, Drayton B, Thomas M, Tang B, O’Connell T, Crino M, et al. Impact and acceptance of a state-wide policy to remove sugar-sweetened beverages in hospitals in New South Wales, Australia. Health Promot J Austr 2021;32(3):444–50. CrossRef PubMed

- Eisenberg Y, Vanderbom KA, Harris K, Herman C, Hefelfinger J, Rauworth A. Evaluation of the Reaching People with Disabilities through Healthy Communities project. Disabil Health J 2021;14(3):101061. CrossRef PubMed

- Escaron AL, Martinez C, Vega-Herrera C, Enger SM. RE-AIM analysis of a community-partnered policy, systems, and environment approach to increasing consumption of healthy foods in schools serving low-income populations. Transl Behav Med 2019;9(5):899–909. CrossRef PubMed

- Feyerherm L, Tibbits M, Wang H, Schram S, Balluff M. Partners for a healthy city: implementing policies and environmental changes within organizations to promote health. Am J Public Health 2014;104(7):1165–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Garcia KM, Garney WR, Primm KM, McLeroy KR. Evaluation of community-based policy, systems, and environment interventions targeting the vending machines. Fam Community Health 2017;40(3):198–204. CrossRef PubMed

- Garcia KM, Martin E, Garney WR, Primm KM. Qualitative analysis of partnerships’ effect on implementation of a nationally led community-based initiative. Health Promot Pract 2018;19(5):775–83. CrossRef PubMed

- Garney WR, Szucs LE, Primm K, King Hahn L, Garcia KM, Martin E, et al. Implementation of policy, systems, and environmental community-based interventions for cardiovascular health through a national not-for-profit: a multiple case study. Health Educ Behav 2018;45(6):855–64. CrossRef PubMed

- Garney WR, Patterson MS, Garcia K, Muraleetharan D, McLeroy K. Interorganizational network findings from a nationwide cardiovascular disease prevention initiative. Eval Program Plann 2020;79:101771. CrossRef PubMed

- Garvin CC, Sriraman NK, Paulson A, Wallace E, Martin CE, Marshall L. The business case for breastfeeding: a successful regional implementation, evaluation, and follow-up. Breastfeed Med 2013;8(4):413–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Giles CM, Kenney EL, Gortmaker SL, Lee RM, Thayer JC, Mont-Ferguson H, et al. Increasing water availability during afterschool snack: evidence, strategies, and partnerships from a group randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43(3 Suppl 2):S136–42. CrossRef PubMed

- Gollub EA, Kennedy BM, Bourgeois BF, Broyles ST, Katzmarzyk PT. Engaging communities to develop and sustain comprehensive wellness policies: Louisiana’s schools putting prevention to work. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E34. CrossRef PubMed

- Hardison-Moody A, Dunn C, Hall D, Jones D, Newkirk L, Thomas J, et al. Multi-level partnerships support a comprehensive faith-based health promotion program. Journal of Extension 2011;49(6):6IAW5.

- Hardison-Moody A, Fuller S, Jones L, Franck K, Rodibaugh R, Washburn L, et al. Evaluation of a policy, systems, and environmental-focused faith-based health promotion program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2020;52(6):640–5. CrossRef PubMed

- Hearst MO, Jimbo-Llapa F, Grannon K, Wang Q, Nanney MS, Caspi CE. Breakfast is brain food? The effect on grade point average of a rural group randomized program to promote school breakfast. J Sch Health 2019;89(9):715–21. CrossRef PubMed

- Hearst MO, Shanafelt A, Wang Q, Leduc R, Nanney MS. Altering the school breakfast environment reduces barriers to school breakfast participation among diverse rural youth. J Sch Health 2018;88(1):3–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Holston D, Stroope J, Cater M, Kendall M, Broyles S. Implementing policy, systems, and environmental change through community coalitions and extension partnerships to address obesity in rural Louisiana. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E18. CrossRef PubMed

- Honeycutt S, Carvalho M, Glanz K, Daniel SD, Kegler MC. Research to reality: a process evaluation of a mini-grants program to disseminate evidence-based nutrition programs to rural churches and worksites. J Public Health Manag Pract 2012;18(5):431–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Jernigan VBB, Williams M, Wetherill M, Taniguchi T, Jacob T, Cannady T, et al. Using community-based participatory research to develop healthy retail strategies in Native American-owned convenience stores: the THRIVE study. Prev Med Rep 2018;11:148–53. CrossRef PubMed

- Kao J, Woodward-Lopez G, Kuo ES, James P, Becker CM, Lenhart K, et al. Improvements in physical activity opportunities: results from a community-based family child care intervention. Am J Prev Med 2018;54(5 Suppl 2):S178–85. CrossRef PubMed

- Kegler MC, Honeycutt S, Davis M, Dauria E, Berg C, Dove C, et al. Policy, systems, and environmental change in the Mississippi Delta: considerations for evaluation design. Health Educ Behav 2015;42(1 Suppl):57S–66S. CrossRef PubMed

- Kelly C, Clennin MN, Barela BA, Wagner A. Practice-based evidence supporting healthy eating and active living policy and environmental changes. J Public Health Manag Pract 2021;27(2):166–72. CrossRef PubMed

- Leser KA, Liu ST, Smathers CA, Graffagnino CL, Pirie PL. Adoption, sustainability, and dissemination of chronic disease prevention policies in community-based organizations. Health Promot Pract 2021;22(1):72–81. CrossRef PubMed

- Long CR, Rowland B, Langston K, Faitak B, Sparks K, Rowe V, et al. Reducing the intake of sodium in community settings: evaluation of year one activities in the Sodium Reduction in Communities program, Arkansas, 2016-2017. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:E160. CrossRef PubMed

- Long CR, Rowland B, McElfish PA. Intervention to improve access to fresh fruits and vegetables among Arkansas food pantry clients. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E09–09. CrossRef PubMed

- Martin SL, Maines D, Martin MW, MacDonald PB, Polacsek M, Wigand D, et al. Healthy Maine Partnerships: policy and environmental changes. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6(2):A63. PubMed

- McGladrey M, Carman A, Nuetzman C, Peritore N. Extension as a backbone support organization for physical activity promotion: a collective impact case study from rural Kentucky. J Phys Act Health 2020;17(1):62–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Molitor F, Doerr C. SNAP-Ed policy, systems, and environmental interventions and caregivers’ dietary behaviors. J Nutr Educ Behav 2020;52(11):1052–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Murriel AL, Kahin S, Pejavara A, O’Toole T. The high obesity program: overview of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and cooperative extension services efforts to address obesity. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E25. CrossRef PubMed

- O’Hara-Tompkins N, Crum G, Fincham H, Lewis D, Bowen E, Murphy E. Opportunities for impact: health promotion in rural early care opportunities for impact: health promotion in rural early care and education environments. Journal of Extension 2021;58(6).

- Ratigan AR, Lindsay S, Lemus H, Chambers CD, Anderson CA, Cronan TA, et al. Factors associated with continued participation in a matched monetary incentive programme at local farmers’ markets in low-income neighbourhoods in San Diego, California. Public Health Nutr 2017;20(15):2786–95. CrossRef PubMed

- Robles B, Barragan N, Smith B, Caldwell J, Shah D, Kuo T. Lessons learned from implementing the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education Small Corner Store Project in Los Angeles County. Prev Med Rep 2019;16:100997. CrossRef PubMed

- Robles B, Wright TG, Caldwell J, Kuo T. Promoting congregant health in faith-based organizations across Los Angeles County, 2013-2016. Prev Med Rep 2019;16:100963. CrossRef PubMed

- Ryan-Ibarra S, DeLisio A, Bang H, Adedokun O, Bhargava V, Franck K, et al. The US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – education improves nutrition-related behaviors. J Nutr Sci 2020;9:e44. CrossRef PubMed

- Saunders RP, Wilcox S, Jake-Schoffman DE, Kinnard D, Hutto B, Forthofer M, et al. The Faith, Activity, and Nutrition (FAN) dissemination and implementation study, Phase 1: implementation monitoring methods and results. Health Educ Behav 2019;46(3):388–97. CrossRef PubMed

- Schroeder M, Grannon K, Shanafelt A, Nanney MS. Role of Extension in improving the school food environment. Journal of Extension 2018;56(7):7IAW2.

- Schwarte L, Samuels SE, Capitman J, Ruwe M, Boyle M, Flores G. The Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program: changing nutrition and physical activity environments in California’s heartland. Am J Public Health 2010;100(11):2124–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Schwartz R, Ellings A, Baisden A, Goldhammer CJ, Lamson E, Johnson D. Washington “Steps” Up: a 10-step quality improvement initiative to optimize breastfeeding support in community health centers. J Hum Lact 2015;31(4):651–9. CrossRef PubMed

- Seguin RA, Folta SC, Sehlke M, Nelson ME, Heidkamp-Young E, Fenton M, et al. The Strong Women Change Clubs: engaging residents to catalyze positive change in food and physical activity environments. J Environ Public Health 2014:162403. CrossRef PubMed

- Shin A, Surkan PJ, Coutinho AJ, Suratkar SR, Campbell RK, Rowan M, et al. Impact of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: an environmental intervention to improve diet among African American youth. Health Educ Behav 2015;42(1 Suppl):97S–105S. CrossRef PubMed

- Subica AM, Grills CT, Villanueva S, Douglas JA. Community organizing for healthier communities: environmental and policy outcomes of a national initiative. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(6):916–25. CrossRef PubMed

- Tomayko EJ, Prince RJ, Hoiting J, Braun A, LaRowe TL, Adams AK. Evaluation of a multi-year policy-focused intervention to increase physical activity and related behaviors in lower-resourced early care and education settings: Evaluation of a multi-year policy-focused intervention to increase physical activity and related behaviors in lower-resourced early care and education settings: Active Early 2.0. Prev Med Rep 2017;8:93–100. CrossRef PubMed

- Trieu K, Webster J, Jan S, Hope S, Naseri T, Ieremia M, et al. Process evaluation of Samoa’s national salt reduction strategy (MASIMA): what interventions can be successfully replicated in lower-income countries? Implement Sci 2018;13(1):107. CrossRef PubMed

- Wallace HS, Franck KL, Sweet CL. Community coalitions for change and the policy, systems, and environment model: a community-based participatory approach to addressing obesity in rural Tennessee. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16(9):E120. CrossRef PubMed

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications Inc; 2020.

- Kegler MC, Swan DW. An initial attempt at operationalizing and testing the Community Coalition Action Theory. Health Educ Behav 2011;38(3):261–70. CrossRef PubMed

- Wilder Foundation. Collaboration Factors Inventory. https://www.wilder.org/wilder-research/resources-and-tools. Accessed June 30, 2022.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. Collaboration Framework. https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/whatworkswisconsin/resources-for-community-init/. Accessed June 30, 2022.

- Brennan LK, Brownson RC, Orleans CT. Childhood obesity policy research and practice: evidence for policy and environmental strategies. Am J Prev Med 2014;46(1):e1–16. CrossRef PubMed

- Honeycutt S, Leeman J, McCarthy WJ, Bastani R, Carter-Edwards L, Clark H, et al. Evaluating policy, systems, and environmental change interventions: lessons learned from CDC’s Prevention Research Centers. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E174. CrossRef PubMed

- Savoie-Roskos MR, DeWitt K, Coombs C. Changes in nutrition education: a policy, systems, and environmental approach. J Nutr Educ Behav 2018;50(5):431. CrossRef PubMed

- Franck K, Shelnutt K. A Delphi study to identify barriers, facilitators and training needs for policies, systems and environmental interventions in nutrition education programs. J Nutr Educ Behav 2016;48(7 Suppl):S45. CrossRef

- Shah HD, Adler J, Ottoson J, Webb K, Gosliner W. Leaders’ experiences in planning, implementing, and evaluating complex public health nutrition interventions. J Nutr Educ Behav 2019;51(5):528–38. CrossRef PubMed

- Herman DR, Blom A, Tagtow A, Cunningham-Sabo L. Implementation of an Individual + Policy, System, and Environmental (I + PSE) technical assistance initiative to increase capacity of MCH nutrition strategic planning. Matern Child Health J 2022. CrossRef PubMed

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Green LW. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39(1):27–53. CrossRef PubMed

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic diseases in America. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2021.

Tables

| I+PSE action component | Definition for healthy eating and active living (HEAL) |

|---|---|

| 1. Strengthen individual knowledge and skills | Enhance individual’s, or household’s decision-making and capability of participating in or benefitting from HEAL. |

| 2. Promote community engagement and education | Connect with diverse groups of people to inform them about the benefits of HEAL and to establish bi-directional communication, trust, and support to advance HEAL approaches. |

| 3. Activate intermediaries and service providers | Inform and educate intermediaries and service providers who transmit information about HEAL to others. |

| 4. Facilitate partnerships and multisector collaborations | Foster relationships and cultivate multisector collaborations with stakeholders about individual, community, and/or population approaches to HEAL. |

| 5. Align organizational policies and practices | Revise or adapt policies, procedures, and practices within institutions that support HEAL. |

| 6. Foster physical, natural, and social settings | Design, foster, and maintain physical (built), natural (ecosystems), and social settings within institutions and public environments that support HEAL. |

| 7. Advance public policy and legislation | Develop strategies to inform change to laws, regulations, and public policies (local, state, federal) that support HEAL. |

Abbreviations: HEAL, healthy eating active living; I+PSE, Individual Plus Policy, Systems, and Environmental Framework for Action.

a Adapted from Tagtow et al (12).

| Author, year (reference) | Funding source | Initiative name; purpose(s) | Setting | Length | I+PSE Framework components aligned with evaluation strategies a | Authors’ identified accomplishments and challenges; coder comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abildso, 2019 (19) | CDC Community Transformation Grant | Change the Future West Virginia; evaluate adoption and reach of nutrition-based PSE in food desert | 638 Schools, 120 farmers markets, 47 retail food outlets | 3 years | Online survey, (weak) [3]; Online survey, weak [4]; documentation, online survey [5]; online survey [6]. Evaluation methods: online survey of participating officials in schools, farmers markets, and outlets; documentation: copies of signed agreements with farmers markets and retail food outlets. RE-AIM Framework used | Accomplishments: Schools in 48 of 55 counties implemented farm-to-school activities; 2 of 3 farmers markets signed collaboration agreements; hiring of personnel with trust and connections was valuable for improving process; changes were easier in local grocery stores than in national stores. Challenges: Funding ended abruptly, and many objectives were not sustained. Lack of resource availability limited progress. Coder comments: Trainings and local connections (personnel-related implementation) important but give minimal details on how this was done. |

| Agner, 2020 (20) | CDC and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | Healthy Hawai‘i Initiative (HHI); statewide effort to prevent and control chronic disease, extend and increase the quality of Hawaiians’ lives, and address health disparity | Private and nonprofit organizations, schools, general public | Ongoing since 2000 | 10 In-depth, semi-structured interviews [4, 5, 6, 7]. Evaluation methods: 10 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with key informants and systematic literature review of HHI reports and articles. Culture of Health Action Framework; 1) creating health values, 2) cross-sectoral collaboration, 3) healthier communities, 4) strengthening health services and systems | Accomplishments: HHI has capitalized on relationship building, data sharing, and storytelling to encourage a shared value of health among lawmakers, efforts led to development of health policy champions; deemed overall a very successful program. Challenges: Cultural differences sometimes led to implementation pushback. Coder comments: Details of how triangulation was conducted or supports results is unclear. |

| Arriola, 2017 (21) | CDC funded Emory Prevention Research Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network to provide mini grants | Prevention Strategies that Work; measured congregants’ perceptions of healthfulness of church environment, policies, and social support, and their physical activity and dietary behaviors in and out of church | 6 Faith-based organizations in Georgia | 12 months | No evaluation [3]; pre and post survey [5]; pre and post survey [6]. Evaluation methods: pre and post surveys administered to church members: pre (baseline) and post 1 year after | Accomplishments: increase in perceived healthy foods served at church associated with overall healthy foods eaten. Challenges: No significant relationship between changes in church physical activity environment and general physical activity behavior; longevity/ sustainability limited. Coder comments: measured “intention to use” for physical activity instead of actual behavior |

| Askelson, 2019 (22) | USDA funded Iowa Department of Education Team Nutrition program | [No named initiative]; describe implementation and results of lunchroom intervention using principles of behavioral economics | 6 rural middle schools in Iowa | 1 school year | Online survey [2]; semi-structured interview [3, 4]; lunchroom assessment, production records, semi-structured interview [6]. Evaluation methods: Online pre- and post-surveys assessed students’, parents’, and food service staff’s perceptions of the lunchroom; semi-structured telephone interviews to assess the experiences and perceptions of food service directors; lunchroom assessment tool assessed environment by measuring criteria during lunch period walk-throughs; production measuring lunch staff ordering/ preparation of healthy foods | Accomplishments: increased lunchroom assessment scores for 5 of 6 middle schools; 4 schools increased servings of healthy food; directors reported intervention as feasible long-term and well received; improved communication with students. Challenges: consumption not measured, no measure of staff and student interaction or education or how relationships between the two improved. Coder comments: production records not reflecting serving; lunchroom assessment not quantitative |

| Balis, 2019 (23) | SNAP-ED, EFNEP, University of Wyoming Extension | Take the Stairs, Wyoming!; increase physical activity in workplaces using PSE; implementation using posters encouraging stairway use | 32 Wyoming businesses and organizations with elevators | 6 months | Opportunistic interviews and site observations [6]. Evaluation methods: interviews with Extension Service health educators and observations of businesses and organizations | Accomplishments: posters widely adopted and implemented. Challenges: capturing reach, effectiveness, and maintenance was challenging because health educators found evaluation burdensome; therefore, difficult to tell whether posters were effective at increasing physical activity levels; lack of data collection adherence by health educators. Coder comments: limited evaluation. |

| Berman, 2018 (24) | J.R. Albert Foundation, Kansas Health Foundation, and Health Care Foundation of Greater Kansas City | Healthy Lifestyles Initiative; increase healthy eating and physical activity, and reduce obesity and disparities through PSE approaches | Local children’s hospital, 218 community partners and 170 community organizations (schools, childcare providers, health care providers, businesses, nonprofit community organizations, government organizations) | 1 year | Online survey [1]; focus groups and online survey [2]; online survey [3]; weak online survey [4]; online survey [5]. Evaluation methods: online survey emailed to partners, self-reporting initiative implementation, focus group to determine what health messaging would be the best/ most desired in targeted settings. |

Accomplishments: educational handouts and posters most commonly used materials; partnerships and reviewing wellness policies most common activities; positive association between making an action plan and number of implementation strategies with activity implementation and material use. Challenges: partners reported wanting increased support; progress/ implementation slow because of lack of resources, communication, and need for additional materials and trainings (although receiving materials was not associated with material usage). Coder comments: minimal information on how self-reporting was standardized |

| Bunnell, 2012 (1) | CDC, US Department of Health and Human Services, county health departments | Communities Putting Prevention to Work; develop PSE plans for decreasing obesity through nutrition and physical activity, tobacco use, and secondhand smoke exposure | 50 Communities (14 large cities, 12 urban areas, 21 small cities and rural counties, and 3 tribes in 32 states and District of Columbia) | 2 years | No evaluation [3, 4]; milestones and action plans [5, 6]. Evaluation methods: review of action plans and outcome objectives, and quarterly reporting on outcome objectives and milestones | Accomplishments: more than one-third of communities advanced their obesity and tobacco-use strategies within 12 months; tobacco interventions had higher population reach than obesity interventions. Challenges: Implementation varied significantly across interventions. Reach was limited (35%–50%) for obesity programming. Coder comments: Evaluation plan discussed in minimal detail; vague and difficult to follow. |

| Castillo, 2019 (25) | CDC | Working on Wellness; PSE intervention for expanding bicycle infrastructure and opportunities for physical activity | General population (860,861 residents) of Hidalgo County, Texas | 3 years | No evaluation [2, 3, 4]; no evaluation described but stated that it occurred [5, 6]. Evaluation methods: Baseline needs assessment of built environment; no further evaluation strategies described | Accomplishments: More than 5 miles of bike lanes installed; bike safety and group rides program initiated; Bicycle Friendly Business Program (57 bicycle racks installed) implemented; 9 of 10 bike trail plans implemented). Challenges: sustainability questioned; partner involvement not fully sustained. Coder comments: No measure on how residents’ use, health, behavior changed, only that access increased. No details on how reporting was facilitated. |

| Cheadle, 2010, Cheadle, 2012 (26,27) | Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Benefit Program | Northern California initiative (Healthy Eating, Active Living –Community Health Initiative); to promote population-level improvements in intermediate outcomes (physical activity levels, proportion eating healthy diet) and long-term improvements in related health outcomes | 3 largely ethnic minority communities with populations of 37,000–52,000; stakeholders were health care sites, worksites, neighborhoods, schools, food stores, and restaurants | 5 years | Telephone survey of adults, school-based survey of youth, fitness test, height and weight measured [1]; interview and photovoice [2, 4]; no evaluation [3, 7]; DOCC; Photovoice [5]; DOCC; Photovoice [6]. Evaluation methods: telephone survey of members accessing Kaiser Permanente health services, pre/post surveys of youth in fitness program measuring physical activity and nutrition, pre/post fitness test of youth, height and weight measurements taken with a few participants, DOCC database tracked reach (number exposed and number affected) to quantify implementation, key stakeholder interviews and Photovoice to gather community opinion and perspective on initiative | Accomplishments: 76 Strategies across 3 communities, high dose interventions to increase youth physical activity, results of youth survey inconclusive. Challenges: Lack of long-term effects due to stakeholder, student, and patient turnover; telephone survey response rates too low to provide adequate information. Coder comments: measuring youth population change was resource intensive; lack of longitudinal measures; I+PSE 5 and 6 potentially sustainable. |

| Cheadle, 2016 (28) | Department of Health and Human Services, CDC Community Transformation Grants, and Partnership to Improve Community Health | King County Communities Putting Prevention to Work; PSE changes to reduce obesity and tobacco use | Schools, local government, community organizations (supported by public health department) across King County, Washington. Consisted of 7 low-income communities (652,000 residents) | 24 months | Interviews [2]; no evaluation [3, 7]; key documents, meeting minutes and attendance, online surveys, tracked advocacy efforts [4]; interviews [5]; interviews, environmental assessments [6]. Evaluation methods: Residents surveyed online, interviews with key stakeholders, observed activities, assessed environment, tracked joint advocacy efforts, reviewed key documents (ie, project planning, action summaries), meeting attendance, estimated number of residents reached | Accomplishments: 22 of 24 strategies achieved significant progress; dyad of technical assistance provider plus champion were key to success; unable to gain joint use agreement. Challenges: More information/ discussion necessary on long-term policy. Coder comments: Environmental assessment seems weak, not standardized |

| Coleman, 2012 (29) | USDA National Research Initiative Award | Healthy Options for Nutrition Environments in Schools; randomized group trial of schools that implemented school nutrition policy and environmental changes to reduce unhealthy foods and beverages on campus, develop nutrition services as the main provider for healthy eating, and promote staff modeling of healthy eating | 1 Low-income school district with 6 elementary schools and 2 middle schools | 3 years | Interviews, height and weight measured [2]; no evaluation [3]; policy document review, environmental assessment, interviews (parent, student, teacher), fundraising results [5]; environmental assessment, count outside beverages per child per week in cafeteria and at recess [6]. Evaluation methods: Interviews of parents, students, and teachers regarding implementation and opinions of PSE changes, self-reported student height and weight, number of outside foods and beverages counted in observation, environment assessment by counting products in trash bins after lunch period, semi-structured interviews with school district administrators and principals, review of policy documents, funding results (money raised and attendance). Model/framework: Plan-Do-Study-Act, Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s rapid improvement process model | Accomplishments: Outside food and beverages per child per week decreased for intervention schools and increased for control schools over time (especially for unhealthy items); changes in rates of obesity were similar in both intervention and control schools. Challenges: Low participant buy-in; unsure whether due to resources or engagement. Coder comments: No exploration of why no significant changes seen between two conditions. |

| Cranney, 2021 (30) | New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health, Prevention Research Collaboration | The Healthy Food and Drink in NSW Health Facilities for Staff and Visitors; aims to increase availability and promotion of healthy food and drink options in food outlets in NSW Health facilities | 15 NSW Local Health Districts and 3 Specialty Health Networks; 26 public hospitals and health facilities and 691 food outlets (eg, kiosks, vending machines, coffee shops) | 1 year | Audit [5]; audit and survey [6]. Evaluation methods: Audit of random samples (environment and adherence to policy); consumer intercept survey | Accomplishments: Proportion of outlets that removed sugary beverages increased from 58.0% to 96.3%; majority of outlets supported removal, with nearly half reporting it would improve people’s health. Challenges: Baseline not obtained for nearly 2/3 of implementation locations; baseline data collection seemed to “motivate” changes. Coder comments: Evaluation done only in a portion of locations (both audit and intercept survey). No measure of how consumers engaged with policy and environmental changes. Strength: Audit collection tool was standardized and auditors were trained. |

| Eisenberg, 2021 (31) | CDC | Reaching People with Disabilities Through Healthy Communities; infuse disability inclusion into PSE changes promoting healthy living (help improve access to healthy choices for community residents with disabilities) | 10 Communities across Iowa, Montana, New York, Ohio, and Oregon | 2-1/2 years | The Community Health Inclusion Index (CHII) assessments [5, 6]; walkability audits; walkability audits, CHII assessments [7]. Evaluation methods: CHII assessments; walkability audits; CHII questions on level of inclusion; recorded data on standardized spread sheet that updated quarterly, content analysis. Framework: Guidelines, Recommendations, Adaptations Including Disability (GRAIDs) | Accomplishments: Implemented 507 inclusive PSEs, 466 were environmental changes, 25 systems changes, and 16 policy changes. Strong internal validity. Challenges: Inability to note intersect. Coder comments: Insufficient description of content in assessment; assumed from reported evidence. |

| Escaron, 2019 (32) | CDC | [No name noted]; promote healthy eating throughout the school day and in after-school programs | 19 School and after-school programs (Boys and Girls Club and YMCA) in southeast Los Angeles, California | 4 years | The Healthy Afterschool Activity and Nutrition Documentation Instrument (HAAND) interviews [3]; program records, the Wellness School Assessment Tool (WellSAT) 2.0 [5]; HAAND interview, HAAND pre- and post- assessment, WellSAT 2.0 [6]; no evaluation [7]. Evaluation methods: Interviews with program staff regarding effectiveness of trainings, their opinions of the HAAND-based guidelines, HAAND assessment pre–post with rubric to evaluate policy, program records regarding trainings/ engagement, WellSat 2.0 to evaluate quality of policy/ implementation. Evaluated via RE-AIM framework | Accomplishments: Reached 43.5% of priority student population. Improvement in wellness policy quality and after-school practices pre- to post-intervention. Challenges: Pushback and lack of communication from some district administration; limited implementation. No follow-up evaluation. Coder comments: Very brief mention of training; weak measure of student engagement. |

| Feyerherm, 2014 (33) | CDC Communities Putting Prevention to Work | Partners for a Healthy City; collaborations with local organizations to implement policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity; develop partner engagement kit, recruit community trainers, and provide technical assistance | 346 Organizations: faith-based organizations, businesses, physician offices, and agencies in Douglas County, Nebraska | 2 years | No evaluation [2, 3, 4, 6]; online assessment tool, number of signed letters of intent [5]. Evaluation methods: Online assessment tool for baseline of policy quality, follow-up assessment to evaluate new policy implementation, number of letters of intent to implement at least 1 policy | Accomplishments: 92% of organizations implemented 1 new policy or expanded a current policy; 952 policy changes total; careful selection of community trainers, wide range of policies, alignment of initiative with organization initiatives, and incentives contributed to success. Challenges: No evaluation on whether or not 1 policy change resulted in many more. Coder comments: Letters of intent weak form of evaluation. |

| Garcia, 2017; Garcia 2018 (34,35) | CDC, American Heart Association | Accelerating National Community Health Outcomes Through Reinforcing Partnerships Program; PSE interventions to increase healthy food options in vending machines | 8 Communities, state capitol, city building, community organization, vending machines | 16 months | No evaluation [1, 2, 3, 4]; assessment [5, 6]. Evaluation methods: Nutrition Environment Measures survey vending assessment to evaluate environment at baseline and post initiative | Accomplishments: 63% of vending machines had healthier food or beverages at follow-up. Challenges: Pushback from community about vending changes and delays in follow-up because of vending contracts and other priorities; institutional and community buy-in was important for implementation; 8 communities assessed baseline, but only 3 communities assessed follow-up. Coder comments: 1,2,3,4 not evaluated. Question whether environment assessment really evaluated I+PSE component 5 (policy) |

| Garney, 2018 (36) | CDC, American Heart Association | Accelerating National Community Health Outcomes Through Reinforcing Partnerships Program; Multiple case study design to implement PSE interventions to increase access to healthy foods and beverages, physical activity, and smoke-free environments | 6 nonprofits (and surrounding communities) in 6 states | Began in May 2015 [length of time unknown] | Action plan assessment, interviews [2]. Evaluation methods: Interviews with program staff and community partners; Quality of Action Plan Assessment Framework, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, State Plan Index Tool | Accomplishments: Implementation-ready communities felt they were most successful in community engagement, even though they were also able to successfully implement PSE interventions. Challenges: Lack of time, lack of follow-up, and difficulty accessing key stakeholders impeded capacity-building communities’ progress. Both types ultimately received community support; just took longer in capacity-building communities. Capacity-building sites laid the groundwork for change but struggled to achieve tangible outcomes. Coder comments: Interviews implied I+PSE component 3 happened. No measure that policy I+PSE component 5 was implemented. |

| Garney, 2020 (37) | CDC | Accelerating National Community Health Outcomes through Reinforcing Partnerships Program; preventing chronic disease by targeting cardiovascular disease risk factors (access to fruits and vegetables, physical activity, and smoke-free environments) | 15 community-based cardiovascular disease prevention partnership networks in the Northeast, South, Midwest, and Western US. 39% of the communities had a poverty rate below the state and/or federal rates | 14 months | Interorganizational Network (ION) survey and partner interview [4]. Nutrition Environment Survey [6]. Evaluation methods: ION survey regarding collaboration, interview with partners involved, survey regarding nutrition environment | Accomplishments: 73% of communities met partnership goals. More equal partnerships were correlated with more success than hierarchical ones. Triangulation with qualitative data. Challenges: Limited timeline; low response rate in some networks; level of involvement required unclear. Coder comments: Subjective data interpretation; complex analysis not available for all initiatives. Mentions evaluation of I+PSE component 6 but 6 wasn’t clearly stated as a goal. |

| Garvin, 2013 (38) | Virginia Department of Health, Consortium for Infant and Child Health | Business Case for Breastfeeding program; lactation support program to eliminate breastfeeding barriers by encouraging changes in policy and business environment | 20 businesses in southeastern Virginia | 14 months | No evaluation [1]; lactation assessment form (LAF) ordinal rating and follow-up questionnaire by phone (weak; indirect) [2]; no evaluation [4]; LAF ordinal rating and follow-up questionnaire by phone [5,6]. Evaluation methods: LAF ordinal rating evaluated environment and policy with rubric-based scale, follow-up questionnaire by phone of businesses measuring engagement in environment. Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change adapted to assess stage of organizational change. CDC tool for measuring community-level PSE change adapted to assess worksite policy and environmental changes | Accomplishments: 20 businesses educated, 17 engaged, 15 completed LAF questionnaires; positive engagement and implementation of the Business Case for Breastfeeding toolkit. Challenges: Only implemented in health care businesses. Coder comments: Appears some sites opted out midway because of minimal support/ communication. |

| Giles, 2012 (39) | CDC Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network and Prevention Research Centers Program, Donald and Sue Pritzker Nutrition and Fitness Initiative, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | Out of School Nutrition and Physical Activity Initiative; implement low-cost strategies to provide water after school; increase consumption of water by elementary school–aged children during after-school snack time; increase overall youth health | 20 Randomly selected after-school programs in the Boston, Massachusetts area | 1 School year | No evaluation [2, 3, 4]; observer records [5,6]. Evaluation methods: Observer records from what was served during after-school programs (records noting times per day served, volume by ounce served, frequency served, calories in other beverages served; related caloric consumption calculations) based on social–ecological model and a community-based participatory research approach | Accomplishments: Water served to children increased in programs receiving intervention resources, calorie consumption decreased compared with nonintervention programs. Challenges: 1 school year, only elementary school–aged children. Coder comments: Minimal evaluation of components, no longevity assessment. |

| Gollub, 2014 (40) | CDC | Louisiana’s Tobacco Control Program’s Putting Prevention to Work; engage school communities to create an environment that promotes healthy eating, physical activity, and tobacco-free living | 27 Louisiana Public Schools | 1 School year | Survey, social media progress report, telephone calls [2]; learnings survey, training sessions report visits, best practice reporting [3]; survey (weak), best practice reporting (weak), overall no evaluation [5]. Evaluation methods: Survey of youth behavior/ beliefs, social media campaign/ content report, telephone calls regarding opinion of social media campaigns, regular on-site learnings survey of state team members on lessons learned during planning and implementation processes, reports on what happened during training sessions, monitoring/ documentation of best practices via site reporters | Accomplishments: Environmental changes (eg, physical activity breaks, healthier vending options, tobacco-free campuses) were adopted. Challenges: Only 25 of 27 schools finished. Coder comments: Survey content/ purpose ambiguous, weak evaluation of I+PSE category 5; very focused on I+PSE category 3 |

| Hardison-Moody, 2011 (41) | Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust of Winston-Salem | Faithful Families Eating Smart and Moving More; promote health of low-income faith communities through 9-session EFNEP-led educational series on good nutrition and physical activity; promoted health with environmental and policy changes to support learning | 44 Faith communities in North Carolina | 9 Weeks | Member health assessment [1]; no evaluation [3]; 172 policy and environmental changes enacted [5,6]. Evaluation methods: Member health assessments pre and post, reporting (very vague) | Accomplishments: Communities enacted 172 policy and environmental changes; behavioral changes noted. Challenges: Difficulty in communication between Extension officials and leaders in the faith-based sector; differences in communication/ implementation. Coder comments: No reporting on how policy/ environmental change data presented/ obtained. Evaluation methods not discussed in detail |