Vital Signs: National and State-Specific Patterns of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Among Insured Children Aged 2–5 Years — United States, 2008–2014

Weekly / May 6, 2016 / 65(17);443–450

On May 3, 2016, this report was posted online as an MMWR Early Release.

Susanna N. Visser, DrPH1; Melissa L. Danielson, MSPH1; Mark L. Wolraich, MD2; Michael H. Fox, ScD1; Scott D. Grosse, PhD3; Linda A. Valle, PhD1; Joseph R. Holbrook, PhD1; Angelika H. Claussen, PhD1; Georgina Peacock, MD1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citationKey Points

• Children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be overly active, have trouble paying attention, and/or have difficulty controlling behavior. They have higher rates of grade retention, high school dropout, unintentional injuries, and emergency department visits.

• About 2 million of the more than 6 million children with ADHD were diagnosed as young children aged 2–5 years. Children with more severe ADHD are more likely to be diagnosed early.

• Behavior therapy in the form of “parent training in behavior therapy” is the recommended first-line treatment for young children with ADHD. It works as well as medication without the risk of side effects. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends health care providers advise parents of young children with ADHD to obtain training in behavior therapy and practice that before trying medication.

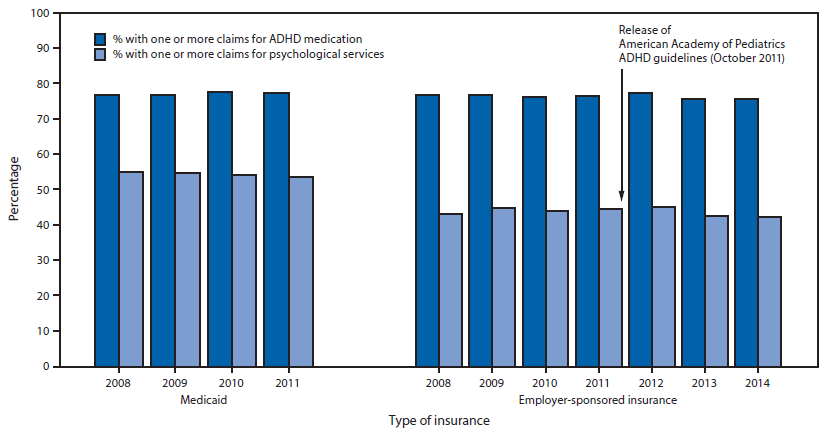

• Among young children with either Medicaid or employer-sponsored insurance, just over 75% of young children in clinical care for ADHD received ADHD medication for treatment. Yet only about 54% of the young children in Medicaid and 45% of the children with employer-sponsored insurance (2011) annually received psychological services (including parent training in behavior therapy). The percentage of young children with ADHD receiving psychological services also has not increased over time.

• Increasing delivery of parent training in behavioral therapy could lead to improved management of ADHD in young children without the side effects of ADHD medication.

• Additional information is available at http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns.

Altmetric:

Abstract

Background: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with adverse outcomes and elevated societal costs. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2011 guidelines recommend “behavior therapy” over medication as first-line treatment for children aged 4–5 years with ADHD; these recommendations are consistent with current guidelines from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for younger children. CDC analyzed claims data to assess national and state-level ADHD treatment patterns among young children.

Methods: CDC compared Medicaid and employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) claims for “psychological services” (the procedure code category that includes behavior therapy) and ADHD medication among children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for ADHD, using the MarketScan commercial database (2008–2014) and Medicaid (2008–2011) data. Among children with ESI, ADHD indicators were compared during periods preceding and following the 2011 AAP guidelines.

Results: In both Medicaid and ESI populations, the percentage of children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for ADHD increased over time; however, during 2008–2011, the percentage of Medicaid beneficiaries receiving clinical care was double that of ESI beneficiaries. Although state percentages varied, overall nationally no more than 55% of children with ADHD received psychological services annually, regardless of insurance type, whereas approximately three fourths received medication. Among children with ESI, the percentage receiving psychological services following release of the guidelines decreased significantly by 5%, from 44% in 2011 to 42% in 2014; the change in medication treatment rates (77% in 2011 compared with 76% in 2014) was not significant.

Conclusions and Comments: Among insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for ADHD, medication treatment was more common than receipt of recommended first-line treatment with psychological services. Among children with ADHD who had ESI, receipt of psychological services did not increase after release of the 2011 guidelines. Scaling up evidence-based behavior therapy might lead to increased delivery of effective ADHD management without the side effects of ADHD medications.

Introduction

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with childhood onset characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity and pervasive, significant functional impairment (1). As of 2011–2012, approximately 6.4 million U.S. children aged 4–17 years (11%) were reported by parents to have a diagnosis of ADHD, a 42% increase since 2003 (2). Nearly one third of children with ADHD (approximately 2 million) received the diagnosis before age 6 years (3). Among children described by their parents as having severe ADHD, half of the cases were diagnosed by age 4 years (2).

Children with ADHD have higher rates of retention in grade level, high school dropout, unintentional injuries, and emergency department visits (4–6). Among one third of children with ADHD, the disorder persists into adulthood; among adults with ADHD, the prevalences of lesser educational and career attainment, co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and death by suicide are higher (7,8). U.S. societal costs of childhood ADHD are estimated at $38–$72 billion annually (9).

ADHD is first diagnosed by a primary care physician among 53% of diagnosed cases in children aged 4–17 years; psychiatrists, psychologists, and other physicians such as neurologists diagnose an additional 18%, 14%, and 15% of cases, respectively (3). In 2011, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) updated guidance for ADHD diagnosis and treatment, recommending behavior therapy as the first line of treatment ahead of stimulant medication (methylphenidate) for treatment of children aged 4–5 years (10). Guidance for child and adolescent psychiatrists also includes the recommendation for psychotherapy before medication in the “very young” (11).

Both behavior therapy in the form of “parent training in behavior therapy” (also called parent behavior training) (Box), and psychostimulant medication for children are effective ADHD treatments among those aged <6 years, but the strength of evidence for behavior therapy exceeds that for psychostimulant medication (12). Behavior therapy might require more time for achievement of full impact on child behavior and might require more resources; however, the impact lasts longer relative to ADHD medication and does not have the adverse health effects associated with these medications (12). Approximately 30% of children aged 3–5 years who take ADHD medications experience adverse effects, most commonly appetite suppression and sleep problems, but also upper abdominal pain (“stomach ache”), emotional outbursts, irritability, lack of alertness, repetitive behaviors and thoughts, social withdrawal, and irritability when the medication wears off (12–14). In a large efficacy trial of methylphenidate, >10% of children aged 3–5 years discontinued treatment because of adverse effects (13). Children aged 3–5 years taking stimulant medication experience annual growth rates that are 20% lower for height (−1.4 cm/year) and 55% lower for weight (−1.3 kg/year) (12). This finding is consistent with the rate of reduced growth among school-aged children taking stimulant medication for ADHD (15). In school-aged children, reduced growth rates tend to attenuate over time (16).

Based on parent-reported survey data collected just before the 2011 AAP guideline release, 53% of children with ADHD aged 4–5 years had received behavior therapy during the preceding year (the survey did not specify whether the therapy was delivered by a parent trained in behavior therapy or by a therapist or some other provider) and 47% had received medication treatment during the preceding week (17). National rates of ADHD treatment among toddlers aged 2–3 years have not been published.

CDC compared rates of psychological services (Box) and medication treatment claims among children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for ADHD in the United States who were insured through Medicaid or employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). In a sample of children with ESI, comparisons were made for years preceding and following release of the 2011 AAP guidelines, to assess changes in rates of medication and psychological services for ADHD treatment among children aged 2–5 years.

Methods

CDC used two administrative claims data sources to characterize ADHD treatment patterns among children aged 2–5 years. Annual data from Medicaid Analytic eXtract files from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2008–2011 were used for children covered by Medicaid insurance for ≥3 continuous months during each calendar year in 29–34 states in each year, depending on data availability and usability (18–20). During 2008–2011, the years with the most complete Medicaid data, data were available for 5–7 million children aged 2–5 years for each year from 29–34 states. Twenty-six states had data available during the entire study period. Data from Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters files for 2008–2014 were used to derive estimates for children covered by ESI. Truven Health provides weights to calculate nationally-representative estimates of children covered by ESI from this convenience sample. In the analytic sample, there were approximately 1 million children aged 2–5 years in the MarketScan commercially insured population in each calendar year. The annual samples from Medicaid and MarketScan data were restricted to children with ≥3 continuous months of coverage whose covered prescription drug claims and mental health visits were included in the analytic databases.*

Three ADHD indicators were developed: receipt of clinical care for ADHD, medication treatment, and receipt of psychological services. Receipt of clinical care for ADHD was defined by two or more outpatient claims† with an International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9) code for ADHD (314.XX) that occurred ≥7 days apart, or one outpatient claim with an ICD-9 ADHD code and two or more claims for FDA-approved ADHD medications that occurred ≥14 days apart.§ Children in clinical care for ADHD were included in the medication treatment group if they had one or more ADHD medication claim per year and in the psychological services group (Box) if they had one or more outpatient claim with a procedure code related to a psychological treatment service¶ per year or both. Comparisons of ADHD indicators over time for Medicaid were restricted to 26 states with complete usable data for 2008–2011. Temporal trends of the three ADHD indicators were assessed by year using the Joinpoint Regression Program (21) to detect any change in trends over time, including changes following the release of the 2011 AAP guidelines. Comparisons of the three indicators were also made using chi-square tests to compare rates by age of the child and year. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to compare these indicators between the Medicaid and ESI populations by year.

Results

Children in Medicaid. In 2011, 106,468 children aged 2–5 years in 34 Medicaid programs received clinical care for ADHD (Table 1), 11,895 (11.2%) of whom were aged 2–3 years. Among 26 assessed state Medicaid programs, the annual percentage of children aged 2–5 years in clinical care for ADHD increased from 1.34% (2008) to 1.50% (2011) (p<0.001) (Table 1). During 2008-2011, approximately 78%–79% of children aged 2–5 years in clinical care for ADHD received one or more prescriptions for ADHD medication, and approximately 51%–53% had one or more claims for psychological services (Table 1) (Figure). Each year during 2008–2011, approximately 40% of children with ADHD received medication only, approximately 15% received psychological services only, approximately 40% received both, and approximately 5% received neither (Table 2). During 2008–2011, approximately 80% of children aged 4–5 years with ADHD received medication, compared with approximately 60% of children aged 2–3 years (p<0.001). Among children with ADHD in Medicaid, approximately 54% and 56% of children aged 4–5 years and 2–3 years, respectively, received psychological services each year; psychological service use was significantly higher among children aged 2–3 years than among children aged 4–5 years for each year (p<0.05).

Children with employer-sponsored insurance. Among children aged 2–5 years with ESI, approximately 36,000–44,000 received clinical care for ADHD each year during 2008–2014 (Table 1), among whom approximately 2,500–3,000 (6%–7%) were aged 2–3 years. The percentage of children aged 2–5 years with ESI who received clinical care for ADHD increased from 0.46% in 2008 to 0.60% in 2014 (p<0.001) (Table 1). During 2011–2014, the percentage of children with ESI and ADHD medication claims did not change significantly (76.6% to 75.7%; p = 0.23); the percentage with psychological services claims decreased 5%, from 44.5% to 42.4% (p = 0.009) (Table 1) (Figure). The Joinpoint analyses did not detect a significant change in trend throughout the entire period (2008–2014) for either medication treatment or psychological services. During 2008–2014, the distribution of children aged 2–5 years with ESI and ADHD across treatment groups each year was just under half for medication only, approximately 15% for psychological services only, approximately 30% for both, and approximately 10% for neither treatment (Table 2).

Each year during 2008–2014, the percentage of children aged 4–5 years with ADHD and ESI who received medication was higher (range = 77%–79%) than for children aged 2–3 years (range = 48%–58%) (p<0.001), and a higher proportion of children with ADHD aged 2–3 years received psychological services than children aged 4–5 years (46%–54% compared with 42%–45%; these differences were statistically significant in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2014).

Children in Medicaid and children with employer-sponsored insurance. For the period covered by both databases (2008–2011), correlations of state-level percentages of children in clinical care for ADHD ranged from 0.74 to 0.87 between databases. During 2008–2011, the percentage of children aged 2–5 years in Medicaid receiving clinical care for ADHD was 2.6–2.9 times greater than that of those with ESI. Across all states with available data, the percentage of children with ADHD medication claims was similar regardless of insurance status, whereas the percentage of children in Medicaid who received psychological services was 13%–22% higher than among that of those in ESI (Table 1). Among both children in Medicaid and children with ESI, ADHD treatment rates varied substantially among states within each calendar year. Three supplemental tables and six U.S. maps showing state-specific data are available at https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/cdc:39038 and https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/cdc:39039.

Conclusions and Comment

In 2011, the latest year for which data are available for both Medicaid and ESI populations, nearly 150,000 insured children aged 2–5 years received clinical care for ADHD, more than two-thirds of whom were Medicaid beneficiaries. Each year during 2008–2011, the percentage of children in Medicaid receiving care for ADHD was more than twice that for children with ESI. This might be accounted for by the higher percentage of children with ADHD in poverty (22), the fact that pediatric ADHD is a basis of eligibility for disability benefits, or differences in behavioral health care practices across health care systems that may result in part from state programs that seek to ensure the delivery of behavioral health services in Medicaid. In both populations, only about 50% of children with ADHD received recommended first-line therapy as measured by receipt of psychological services, whereas approximately three fourths received ADHD medication. ADHD rates varied widely across states in both insured groups, possibly because of differences in how children with ADHD are identified and served in their communities, how these services are documented, or both. There was not an increase in psychological services nor decrease in use of medication after the AAP guidelines release among children with ESI (2011–2014).

Behavior therapy for ADHD, in the form of parent behavior training, and ADHD medications are both recommended ADHD treatments (10,12). However, among children aged ≤5 years, the number and quality of studies demonstrating effectiveness is higher for parent behavior training than for ADHD medication (12). In addition, young children are more susceptible to adverse health effects of ADHD medications, whereas adverse health effects have not been reported for parent behavior training (12). ADHD treatment with behavior therapy, which is typically limited in duration, might be associated with better school outcomes (23) and more cost-effective over a school year than treatment with ongoing medication (24). Further, behavior therapy can also improve problematic behavior in young children who present with symptoms that look like ADHD, such as symptoms of anxiety and oppositional defiant disorder. Collectively, these factors support recommendations (10,11) for parent training in behavior therapy as first-line treatment for children aged ≤5 years with ADHD.

There are barriers to the receipt of evidence-based behavior therapy training for families of young children with ADHD. First, clinical practice change following guideline or policy change takes time, and practices can vary depending on provider knowledge about the guidelines, the scale of the recommended change, and the amount of support provided to physicians (25). Parents and physicians might lack awareness of the recommendations and benefits of behavior therapy. Families might have difficulty identifying and accessing providers of evidence-based behavior therapy, and these services might require more resources initially to access than medication. Behavior therapy might not exist in every community, and scaling up these services might be difficult and costly. To overcome these barriers, policymakers, state agencies, and health professional organizations can continue to educate parents and physicians about recommendations while expanding capacity to provide evidence-based services. State agencies and offices, such as Medicaid and Foster Care, can consider programs and policies designed to increase use of behavior therapy for ADHD, including using Title IV-E funds for the state expansion of evidence-based programs. States might also explore policies that influence prescription patterns based on existing evidence of safety and effectiveness, such as prior-authorization policies. To date, 27 state Medicaid programs have implemented prior-authorization policies for pediatric ADHD medication prescriptions.** However, it is also important to consider strategies to increase access to preferred psychological services, particularly among children who are denied medication authorization.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, the population evaluated was children receiving clinical care for ADHD; thus, these rates do not reflect the overall prevalence of children with ADHD. Second, the identified population did not include children in Medicaid programs for which annual data were not available, children receiving clinical care not covered by insurance, and children with a diagnosis of ADHD who had not received sufficient clinical services to meet the case definition. Third, importantly, the psychological services indicator lacked precision, and it was not possible to assess type or quality of psychological services. An inclusive list of psychological services was used as a proxy for behavior therapy with or without an ADHD ICD-code because there are no ADHD-specific behavior therapy procedure codes, although treatments for other externalizing disorders might benefit ADHD symptoms and impairment (12), and ADHD might not have been listed as the primary or secondary diagnosis in the associated claim. Conversely, not all psychological services could be identified using these data because some might not have been covered by insurance (e.g., self-paid or delivered through the education system). However, rates of psychological services among children in this report were similar to those reported for children aged 4–5 years in 2009–2010 using national parent survey data on behavior therapy for ADHD not conditional on having insurance (17). Fourth, results represent cross-sectional annual percentages and not lifetime diagnosis or treatment patterns. In addition, children might have been counted multiple times if their insurance status changed during the calendar year (e.g., moved to a different state Medicaid program). Finally, MarketScan data include only children with ESI and might not be generalizable to the entire U.S. population of privately insured children. However, in 2014, among the 52% of children aged 0–18 years who had private insurance, 90% were covered by ESI (26).

ADHD is a highly prevalent condition that can lead to poor health and social outcomes (4–9). Despite 2007 and 2011 guidelines recommending behavior therapy as first-line treatment for children aged <6 years with ADHD, during 2008–2014 only about half of children aged 2–5 years with ADHD received psychological services. To effectively mitigate impairments associated with ADHD and minimize risks associated with ADHD medications, it is important to increase the percentage of young children with ADHD who receive evidence-based psychological services, especially parent training in behavior therapy.

Corresponding author: Susanna N. Visser, svisser@cdc.gov, 404-498-3008.

1Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; 2University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, OU Child Study Center; 3Office of the Director, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53:34–46.e2. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Visser SN, Zablotsky B, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH. Diagnostic experiences of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Natl Health Stat Report 2015;81:1–7. PubMedexternal icon

- Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Jacobsen SJ. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28:265–73. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Merrill RM, Lyon JL, Baker RK, Gren LH. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and increased risk of injury. Adv Med Sci 2009;54:20–6. PubMedexternal icon

- Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Identified attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and medically attended, nonfatal injuries: US school-age children, 1997–2002. Ambul Pediatr 2006;6:38–44. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: a prospective study. Pediatrics 2013;131:637–44. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE , Molina BS, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:27–41. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Doshi JA, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, et al. Economic impact of childhood and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:990–1002.e2. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011;128:1007–22. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1532–72. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- Wigal T, Greenhill L, Chuang S, et al. Safety and tolerability of methylphenidate in preschool children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:1294–303. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Storebø OJ, Ramstad E, Krogh HB, et al. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;11:CD009885. PubMedexternal icon

- MTA Cooperative Group. National Institute of Mental Health Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD follow-up: changes in effectiveness and growth after the end of treatment. Pediatrics 2004;113:762–9. PubMedexternal icon

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Morley CP, Spencer TJ. Effect of stimulants on height and weight: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:994–1009. PubMedexternal icon

- Visser SN, Bitsko RH, Danielson ML, et al. Treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children with special health care needs. J Pediatr 2015;166:1423–30.e2. CrossRefexternal icon

- Byrd VLH, Dodd AH. Medicaid policy brief no. 15. Assessing the usability of encounter data for enrollees in comprehensive managed care across MAX 2007–2009: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012.

- Byrd VLH, Dodd AH. Medicaid policy brief no. 22. Assessing the usability of encounter data for enrollees in comprehensive managed care 2010–2011. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015.

- McKinney D, Kidney R, Xu A, Lardiere MR, Schwartz R. Health center reimbursement for behavioral health services in Medicaid. Washington, DC: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2010.

- Joinpoint trend analysis software. 4.2.0 ed.: Washington, DC: National Cancer Institute; 2015. http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/external icon

- US Department of Health and Human Services and Services Administration & Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999.

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA, Waxmonsky JG, et al. Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of adaptive medication and behavioral interventions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016. Epub February 16, 2016. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Page TF, Pelham Iii WE, Fabiano GA, et al. Comparative cost analysis of sequential, adaptive, behavioral, pharmacological, and combined treatments for childhood ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016. Epub January 26, 2016. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Timmermans S, Mauck A. The promises and pitfalls of evidence-based medicine. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:18–28. CrossRefexternal icon PubMedexternal icon

- Kaiser Family Foundation. State health facts: health insurance coverage of children 0–18. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/children-0-18/external icon

* For the Medicaid population, about 97% of enrolled children aged 2–5 years were enrolled for at least 3 continuous months during each calendar year. For the MarketScan sample, approximately 55% of all enrolled children aged 2–5 years had prescription drug and mental health visit claims contributed to the MarketScan data files, and of these, approximately 97% had ≥3 months of continuous enrollment.

† Outpatient claims included physician, outpatient, and clinic services not related to inpatient hospital services, prescription drug services, or long-term care.

§ In order to include all services related to ADHD care, ADHD medication claims that did not include ICD-9 codes were included. FDA-approved medications to treat ADHD in children of any age included amphetamine and mixed amphetamine salts, atomoxetine, clonidine, dextroamphetamine, dexmethylphenidate, guanfacine, lisdexamfetamine, and methylphenidate. Only dextroamphetamine has been approved for use in children as young as age 3 years.

¶ Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes: 90804–90819, 90821–90824, 90826–90829, 90832–90834, 90836–90840, 90845–90847, 90849, 90853, 90857, 99354–99355, and 99510. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes: G0410, G0411, H0035–H0037, H2012–H2013, H2017–H2020, S9480, and T1027. State-specific codes: 1610 (New York); 5003H, 8226A, 8227A, 8228A, 8245A, 8247A, 8248A, 8245S, 8250A, 8250S (Idaho); CDABF, CDACM, CDAEP, CDAKQ (Alaska); G0177 (Nebraska); Y9935 (New Jersey); and Z1840–Z1841, Z1843 (Ohio).

BOX. Definitions of certain terms used in CDC analysis of Medicaid and employer-sponsored insurance claims data among children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

BOX. Definitions of certain terms used in CDC analysis of Medicaid and employer-sponsored insurance claims data among children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Psychological services for ADHD

One or more nonpharmacological treatment services included in a set of current procedure codes. These services could be provided directly to the child with ADHD or to the parent of the child with ADHD as part of the child’s treatment.

Behavior therapy for ADHD

Psychological service interventions that specifically change problematic behavior, including ADHD symptoms, by altering the physical or social contexts in which the behavior occurs. Services can be delivered to the child by a therapist, teacher, parent, or other provider.

Parent training in behavior therapy (also called parent behavior training) for ADHD

A form of behavior therapy that specifically trains parents in methods to modify their child’s problematic behavior, including ADHD symptoms. This form of behavior therapy has been shown by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to have the strongest evidence of effectiveness of any ADHD treatment for children aged <6 years.

TABLE 1. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated treatments received, by type of insurance — United States, 2008–2014

TABLE 1. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated treatments received, by type of insurance — United States, 2008–2014

| Type of insurance | No. of states reporting* | Population in clinical care for ADHD | Children receiving clinical care for ADHD | Children receiving clinical care for ADHD with one or more ADHD medication claim | Children receiving clinical care for ADHD with one or more psychological services claim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid | All reporting states % | States with complete data (n = 26†) % | All reporting states % | States with complete data (n = 26†) % | All reporting states % | States with complete data (n = 26†) % | ||

| 2008 | 32 | 71,162 | 1.39 | 1.34 | 77.6 | 76.6 | 52.7§ | 55.0§ |

| 2009 | 29 | 79,401 | 1.41 | 1.37 | 77.8 | 76.8 | 50.8§ | 54.7§ |

| 2010 | 33 | 94,016 | 1.48 | 1.43 | 78.5 | 77.7 | 51.0 | 54.3 |

| 2011 | 34 | 106,468 | 1.53 | 1.50 | 77.7 | 77.3 | 52.6 | 53.6 |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | Population in clinical care for ADHD (weighted) | National unweighted % | National weighted % | National unweighted % | National weighted % | National unweighted % | National weighted % | |

| 2008 | 35,862 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 77.4 | 76.9 | 43.8 | 43.2 | |

| 2009 | 39,512 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 77.1 | 76.7 | 45.1 | 44.9 | |

| 2010 | 40,184 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 76.3 | 76.2 | 44.2 | 44.0 | |

| 2011 | 41,420 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 77.1 | 76.6 | 44.0 | 44.5 | |

| 2012 | 43,792 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 77.8 | 77.4 | 44.6 | 45.2 | |

| 2013 | 43,465 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 76.2 | 75.8 | 42.1 | 42.6 | |

| 2014 | 42,985 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 76.1 | 75.7 | 41.7 | 42.4 | |

Sources: 2008–2011 Medicaid Analytic eXtract files; 2008–2014 Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters files for employer-sponsored insurance.* States were included in Medicaid analysis if state-level data were available, deemed usable, and the state Medicaid program did not have a policy that resulted in the provision of behavioral health services by another entity that was not paid directly through Medicaid during the calendar year.† The 26 states that had complete usable data for each year during 2008–2011 were Alaska, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.§ Excludes California from pooled percentages for psychological services (unusable data).

FIGURE. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with one or more claims for ADHD medication and one or more claims for psychological services, by type of insurance* — United States, 2008–2014

FIGURE. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with one or more claims for ADHD medication and one or more claims for psychological services, by type of insurance* — United States, 2008–2014

* Data from 26 Medicaid state programs with complete usable data for 2008–2011.

TABLE 2. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated treatments received, by type of insurance, and state reporting status — United States, 2008–2014

TABLE 2. Percentage of insured children aged 2–5 years receiving clinical care for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated treatments received, by type of insurance, and state reporting status — United States, 2008–2014

| Type of insurance | All states with reported data | States with complete data (n = 26*) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid | No. of states reporting† | Both medication and psychological services % | Medication only % | Psychological services only % | Neither medication nor psychological services % | Both medication and psychological services % | Medication only % | Psychological services only % | Neither medication nor psychological services % |

| 2008 | 32 | 38.2§ | 40.8§ | 14.6§ | 6.4§ | 39.8§ | 38.3§ | 15.2§ | 6.7§ |

| 2009 | 29 | 36.5§ | 42.6§ | 14.3§ | 6.6§ | 39.5§ | 38.8§ | 15.2§ | 6.5§ |

| 2010 | 33 | 36.3 | 42.2 | 14.7 | 6.8 | 38.7 | 38.9 | 15.6 | 6.8 |

| 2011 | 34 | 37.1 | 40.6 | 15.5 | 6.8 | 37.8 | 39.5 | 15.7 | 7.0 |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | National unweighted data | National weighted data | |||||||

| Both medication and psychological services % | Medication only % | Psychological services only % | Neither medication nor psychological services % | Both medication and psychological services % | Medication only % | Psychological services only % | Neither medication nor psychological services % | ||

| 2008 | 29.7 | 47.7 | 14.1 | 8.6 | 29.1 | 47.8 | 14.2 | 8.9 | |

| 2009 | 30.8 | 46.3 | 14.3 | 8.6 | 30.3 | 46.4 | 14.6 | 8.7 | |

| 2010 | 29.5 | 46.8 | 14.8 | 8.9 | 29.3 | 46.9 | 14.7 | 9.1 | |

| 2011 | 30.2 | 46.9 | 13.8 | 9.1 | 30.3 | 46.3 | 14.2 | 9.2 | |

| 2012 | 30.9 | 46.9 | 13.8 | 8.5 | 31.1 | 46.3 | 14.1 | 8.5 | |

| 2013 | 27.8 | 48.4 | 14.3 | 9.5 | 28.0 | 47.8 | 14.6 | 9.6 | |

| 2014 | 26.9 | 49.2 | 14.8 | 9.1 | 27.3 | 48.5 | 15.1 | 9.2 | |

Sources: 2008–2011 Medicaid Analytic eXtract files; 2008–2014 Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters files for employer-sponsored insurance.

* The 26 states that had complete usable data for each year during 2008–2011 were Alaska, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

† States were included in Medicaid analysis if state-level data were available, deemed usable, and the state Medicaid program did not have a policy that resulted in the provision of behavioral health services by another entity that was not paid directly through Medicaid during the calendar year.

§ Excludes California from pooled percentages for psychological services (unusable data).

Suggested citation for this article: Visser SN, Danielson ML, Wolraich ML, et al. Vital Signs: National and State-Specific Patterns of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Among Insured Children Aged 2–5 Years — United States, 2008–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:443–450. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6517e1external icon.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are

provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply

endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content

of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of

the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.