1. Introduction

Best Practices for Environmental Cleaning in Global Healthcare Facilities with Limited Resources

The materials on this page were created for use in global healthcare facilities with limited resources, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Environmental cleaning resources designed for U.S. healthcare facilities can be found at Healthcare Environment Infection Prevention.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are a significant burden globally, with millions of patients affected each year. [Reference 1] These infections affect both high- and limited-resource healthcare settings, but in limited-resource settings, rates are approximately twice as high (15 out of every 100 patients versus 7 out of every 100 patients). Furthermore, infection rates within certain patient populations, including surgical patients, patients in intensive-care units (ICU) and neonatal units, are significantly higher in limited-resource settings.

It is well documented that environmental contamination in healthcare settings plays a role in the transmission of HAIs. [References 2, 3] Therefore, environmental cleaning is a fundamental intervention for infection prevention and control (IPC). It is a multifaceted intervention that involves cleaning and disinfection (when indicated) of the environment alongside other key program elements (e.g., leadership support, training, monitoring, and feedback mechanisms).

To be effective, environmental cleaning activities must be implemented within the framework of the facility IPC program, and not as a standalone intervention. It is also essential that IPC programs advocate for and work with facility administration and government officials to budget, and operate and maintain adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure to ensure that environmental cleaning can be performed according to best practices.

1.1 Environmental transmission of HAIs

In a variety of healthcare settings, environmental contamination has been significantly associated with transmission of pathogens in major outbreaks of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Clostridioides difficile (C. diff), and more recently in protracted outbreaks of Acinetobacter baumannii. Outbreak investigations have determined that the risk of patient colonization and infection increased significantly if the patient occupied a room that had been previously occupied by an infected or colonized patient. Therefore, the role of immediate patient care environment—particularly, environmental surfaces within the patient zone that are frequently touched by or in direct physical contact with the patient such as bed rails, bedside tables and chairs—in facilitating survival and subsequent transfer of microorganisms was established. [References 4–10] However, it is important to note that environmental transmission of HAIs can occur by different pathways.

It has also been documented that some healthcare-associated pathogens can survive on environmental surfaces for months.[Reference 3] In 2006, a laboratory-based study documented the survival times of a range of significant healthcare-associated pathogens, including gram-negative bacilli, and found that they could persist much longer in the environment than was previously understood. For example, Acinetobacter spp. survived up to 5 months and Klebsiella spp. up to 30 months. [References 11–12] The actual survival times in healthcare settings vary considerably based on factors such as temperature, humidity, and surface type.

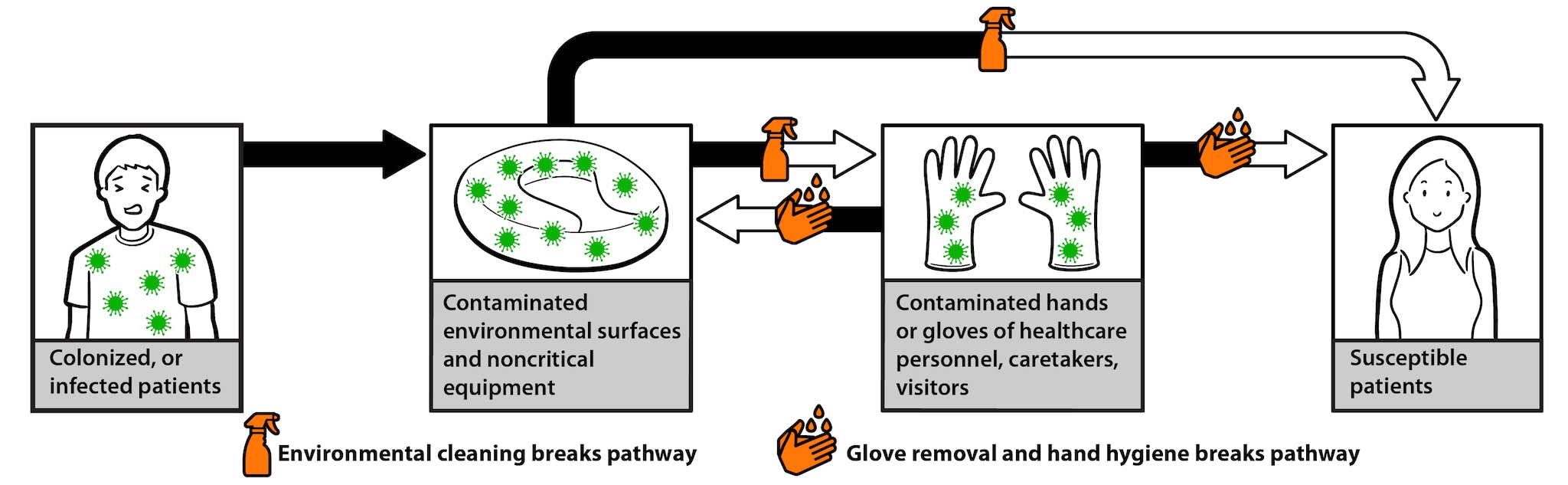

Figure 1 illustrates the environmental transmission pathway in general terms. Microorganisms are transferred from the environment to a susceptible host through:

- contact with contaminated environmental surfaces and noncritical equipment

- contact with contaminated hands or gloves of healthcare workers during the provision of care, as well as by caretakers and visitors

Contaminated hands or gloves will also continue to spread microorganisms around the environment. Figure 1 also shows how these pathways can be broken and highlights that environmental cleaning and hand hygiene (preceded by glove removal, as applicable) can break this chain of transmission.

Figure 1. Contact transmission pathway showing role of environmental surfaces, role of environmental cleaning, and hand hygiene in breaking the chain of transmission

A colonized or infected patient can contaminate environmental surfaces and noncritical equipment. Microorganisms from these contaminated environmental surfaces and noncritical equipment can be transferred to a susceptible patient in two ways:

- If the susceptible patient makes contact with the contaminated surfaces directly (e.g., touches them).

- If a healthcare personnel, caretaker, or visitor makes contact with the contaminated surfaces and then transfers the microorganisms to the susceptible patient.

Contaminated hands or gloves of healthcare personnel, caretakers and visitors can also contaminate environmental surfaces in this way. Proper hand hygiene and environmental cleaning can prevent transfer of microorganisms to healthcare personnel, caretakers, and visitors and to susceptible patients.

Evidence is increasing but remains limited that effective environmental cleaning strategies reduce the risk of transmission and contribute to outbreak control.[References 7, 13–22] Consequently, the use of multiple (i.e., a bundle) interventions as well as an overall multi-modal approach to IPC activities and programs is recommended, for both the outbreak and routine setting.

1.2 Environmental cleaning and IPC

Environmental cleaning is part of Standard Precautions, which should be applied to all patients in all healthcare facilities. It is important to implement environmental cleaning programs within the framework of facility level IPC programs. Where possible—during staff training and education, for example—consider generating synergies and highlighting the relationship between environmental cleaning and hand hygiene activities in preventing environmental transmission of HAIs.

Facility level IPC programs include multiple elements, ranging from surveillance for HAIs to training and education for all healthcare workers on IPC. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined core components of IPC programs in Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level.

Environmental cleaning is addressed explicitly within Core Component 8: Built environment, materials and equipment for IPC at the facility level.

But other components include important aspects for the implementation of environmental cleaning as well, such as:

- Core Component 2: IPC guidelines

- Core Component 3: IPC education and training

- Core Component 6: Monitoring/audit of IPC practices and feedback

At the national level, it is important that these Core Components (2, 3 and 6) include frameworks and guidance to inform facility level approaches to environmental cleaning.

Given the wide range of IPC responsibilities at acute healthcare facilities, implementation of robust IPC programs requires a dedicated, trained IPC team (or at least a focal person). The IPC team should consult and be involved in the technical aspects of environmental cleaning program (e.g., training, policy development). A separate team is recommended for the overall management and implementation of the environmental cleaning program. In small primary care facilities with limited inpatient services, the IPC team or focal person might be directly responsible for managing environmental cleaning activities.

1.3 Environmental cleaning and WASH infrastructure

Healthcare facilities must have adequate water supply and sanitation infrastructure (e.g., safe wastewater disposal) to perform environmental cleaning according to best practices. A recent global report summarized the critical lack of access to basic water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services in healthcare facilities in resource-limited settings, which hinders the ability of facilities to implement effective environmental cleaning programs. [Reference 23]

In response to the identified need to improve WASH in Healthcare facilities, WHO and UNICEF have engaged partners and proposed practical steps to improve WASH services. Notably, this includes using and reporting on:

- harmonized monitoring indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals: Healthcare Facilities, Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP)

- a facility improvement tool to assist incremental improvements to WASH services: Water and Sanitation for Health Facility Improvement Tool ((WASH FIT)): a practical guide for improving quality of care through water, sanitation and hygiene in healthcare facilities

- eight recommended practical steps that provide a roadmap for country improvement in the long term and align with the 2019 World Health Assembly Resolution on WASH in healthcare facilities: WHO | WASH in health care facilities

1.4 Basis and evidence for proposed best practices

The following best practices for environmental cleaning in resource-limited settings are proposed as a standard reference and a resource to:

- supplement existing guidelines

- inform the development of guidelines where needed

- elevate the attention to this critical and under-resourced aspect of healthcare and patient safety

These best practices are derived directly from a variety of best practices and cleaning standard documents from several English-speaking high-resource settings, most notably, the United States of America, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. These documents have been generated by a combination of expert opinion and ranking of the current evidence. See Further reading for a list of the documents that have been used extensively in the development of these best practices.

These best practices were developed by a committee of experts in environmental cleaning in resource-limited settings. Using a consensus-driven process, we have included the best practices most relevant and achievable for the target context.

For example, the best practices in ICUs in this document include more frequent environmental cleaning that recommended in several of the referenced documents because of the increased HAI risk and burden in ICUs in resource-limited settings. Alternatively, the use of no-touch and novel disinfection devices, which are increasingly common in high-resource settings, were excluded from this document because of their prohibitive cost and limited evidence on their effectiveness in reducing HAIs in resource-limited settings.

This is a living document that will be updated and improved as new evidence becomes available.

The following are outside of the scope of this document:

- Cleaning procedures outside of patient care areas, such as offices and administrative areas

- Cleaning of the environment external to the facility buildings (e.g., waste storage areas, ambulances and facility grounds)

- Decontamination and reprocessing of semi-critical and critical equipment

Primary audience:

Full- or part-time cleaning managers, cleaning supervisors, or other clinical staff who assist with environmental cleaning program development and implementation, such as members of existing infection control or hygiene committees.

Secondary audience:

Other staff who assure a clean patient-care environment, such as supervisors of wards or departments, midwives, nursing staff, administrators, procurement staff, facilities management, and any others responsible for WASH or IPC services at the healthcare facility.

1.7 Overview of the document

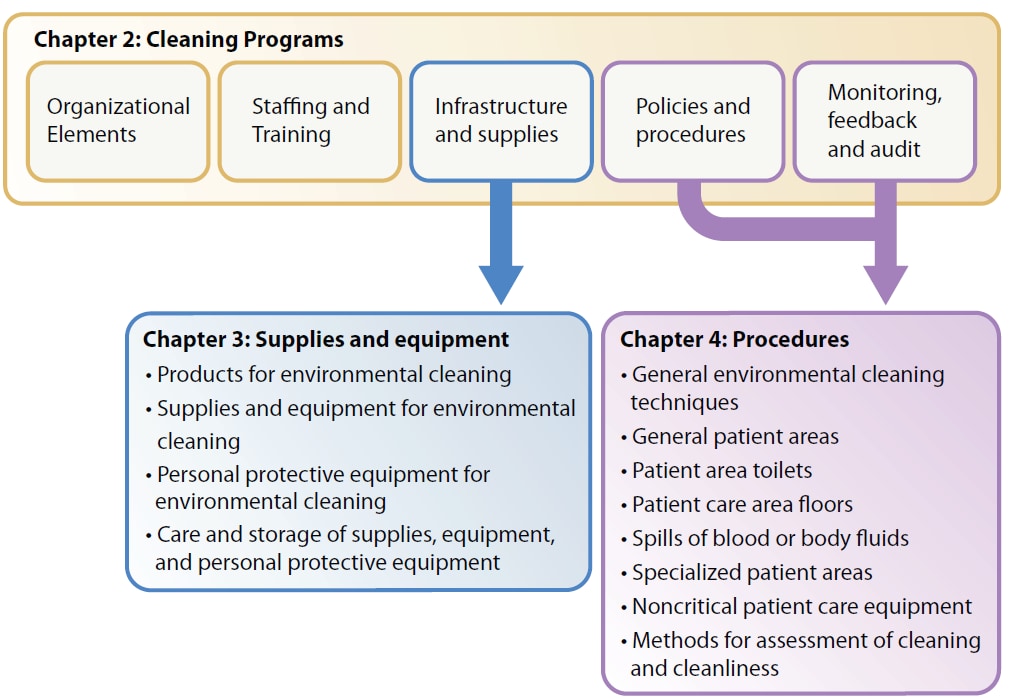

The best practices are divided into three chapters, described below and relationally in Figure 2.

Chapter 2: Environmental Cleaning Programs

- An environmental cleaning program is a structured set of elements or interventions which facilitate implementation of environmental cleaning at a healthcare facility.

- Environmental cleaning programs require a standardized and multi-modal approach and strong management and engagement from multiple stakeholders and departments of the healthcare facility, such as administration, IPC, WASH or facilities management.

- This chapter provides the best practices for implementing environmental cleaning programs for all program mechanisms (managed in-house or contracted), including the key program elements of:

- organization/administration

- staffing and training

- infrastructure and supplies

- policies and procedures

- monitoring, feedback and audit

Chapter 3: Environmental Cleaning Supplies and Equipment

- The selection and appropriate use of supplies and equipment is critical for effective environmental cleaning in patient care areas.

- This chapter provides overall best practices for selection, preparation, and care of environmental cleaning supplies and equipment, including:

- cleaning and disinfectant products

- reusable and disposable supplies

- cleaning equipment

- personal protective equipment (PPE) for the cleaning staff

Chapter 4: Environmental Cleaning Procedures

- It is critical to develop and implement standard operating procedures (SOP) for patient care areas.

- This chapter provides:

- the overall strategies and techniques for conducting environmental cleaning according to best practice based on risk assessment

- Best practices for the frequency, method, and process for every major area in healthcare settings to help users develop tailored SOPs for all patient care areas in their facility, including:

- outpatient areas

- general inpatient areas

- specialized patient areas

- Allegranzi B, Begheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, Pittet D. 2011. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet; 377:9761.

- Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Miller MB, et al. 2010. Role of hospital surfaces in the transmission of emerging healthcare-associated pathogens: norovirus, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter species. Am J Infect Control 38:S25–S33.

- Otter JA, Yezlli S, Salkeld J, French G. 2013. Evidence that contaminated surfaces contribute to the transmission of hospital pathogens and an overview of strategies to address contaminated surfaces in hospital settings. American Journal of Infection Control; 41: S6-S11.

- Huang SS, Datta R, Platt R. 2006. Risk of acquiring antibiotic-resistant bacteria from prior room occupants. Archs Intern Med; 166:1945-1951.

- Drees M, Snydman DR, Schmid CH, et al. 2008. Prior environmental contamination increases the risk of acquisition of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis; 46:678-685.

- Nseir S, Blazejewski C, Lubret R, Wallet F, Courcol R, Durocher A. 2011. Risk of acquiring multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli from prior room occupants in the intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect; 17:1201-1208.

- Datta R, Platt R, Yokoe DS, Huang SS. 2011. Environmental cleaning intervention and risk of acquiring multidrug-resistant organisms from prior room occupants. Archs Intern Med; 171:491-494.

- Shaughnessy MK, Micielli RL, DePestel DD, et al. 2011. Evaluation of hospital room assignment and acquisition of Clostridium difficile Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol; 32:201-206.

- Ajao AO, Johnson K, Harris AD, et al. 2013. Risk of acquiring extended spectrum b-lactamase-producing Klebsiella species and Escherichia coli from prior room occupants in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol; 34:453-458.

- Mitchell BG, Digney W, Ferguson JK. 2014. Prior room occupancy increases risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition. Healthcare Infect; 19:135-140.

- Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. 2006. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis; 6:130.

- Dancer SJ. 2014. Controlling hospital-acquired infection: focus on the role of the environment and new technologies for decontamination. Clin Microbiol Rev; 27:665-690.

- Falk PS, Winnike J, Woodmansee C, Desai M, Mayhall CG. 2000. Outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in a burn unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 21:575-82.

- Rampling A, Wiseman S, Davis L, Hyett AP, Walbridge AN, Payne GC, et al. 2001. Evidence that hospital hygiene is important in the control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 49:109-16.

- Wilcox M., Fawley W., Wigglesworth N., Parnell P., Verity P., Freeman J. (2003) Comparison of the effect of detergent versus hypochlorite cleaning on environmental contamination and incidence of Clostridium difficile J Hosp Infect 54: 109–114.

- Denton M, Wilcox MH, Parnell P, Green D, Keer V, Hawkey PM, et al. 2004. Role of environmental cleaning in controlling an outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii on a neurosurgical intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect 56:106-10.

- Hayden MK, Bonten MJ, Blom DW, Lyle EA, van de Vijver DA, Weinstein RA. 2006. Reduction in acquisition of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus after enforcement of routine environmental cleaning measures. Clin Infect Dis 42:1552-60.

- McMullen K., Zack J., Coopersmith C., Kollef M., Dubberke E., Warren D. (2007) Use of hypochlorite solution to decrease rates of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28: 205–207.

- Dancer SJ, White LF, Lamb J, Girvan EK, Robertson C. 2009. Measuring the effect of enhanced cleaning in a UK hospital: a prospective cross-over study. BMC Med 7:28.

- Wilson AP, Smyth D, Moore G, Singleton J, Jackson R, Gant V, et al. 2011. The impact of enhanced cleaning within the intensive care unit on contamination of the near-patient environment with hospital pathogens: a randomized crossover study in critical care units in two hospitals. Crit Care Med 39:651-8.

- Grabsch EA, Mahony AA, Cameron DR, Martin RD, Heland M, Davey P, et al. 2012. Significant reduction in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization and bacteraemia after introduction of a bleach-based cleaning-disinfection programme. J Hosp Infect 82:234-42.

- Mitchell BG, Hall L, White N, Barnett AG, Halton K, Paterson DL, Riley TV, Gardner A, Page K, Farrington A, Gericke CA, Graves N. 2019. An environmental cleaning bundle and health-care-associated infections in hospitals (REACH): a multicenter, randomized trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP), 2019. WASH in Health Care Facilities: Global Baseline Report 2019. WHO:Geneva.