Vaccine Administration

JoEllen Wolicki, BSN, RN and Elaine Miller, RN, BSN, MPH

Printer friendly version [28 pages]

This chapter summarizes best practices related to vaccine administration, a key factor in ensuring vaccination is as safe and effective as possible. Administration involves a series of actions: assessing patient vaccination status and determining needed vaccines, screening for contraindications and precautions, educating patients, preparing and administering vaccines properly, and documenting the vaccines administered. Professional standards for medication administration, manufacturer instructions, and organizational policies and procedures should always be followed when applicable.

Staff Training and Education

Policies should be in place to validate health care professional’s knowledge of, and skills in, vaccine administration. All health care professionals should receive comprehensive, competency-based training before administering vaccines. Training, including an observation component, should be integrated into health care professionals’ education programs including orientation for new staff and annual continuing education requirements for all staff. In addition, health care professionals should receive educational updates as needed, such as when vaccine administration recommendations are updated or when new vaccines are added to the facility’s inventory. Training should also be offered to temporary staff who may be filling in on days when the facility is short-staffed or helping during peak periods of vaccine administration such as influenza season. Once initial training has been completed, accountability checks should be in place to ensure staff follow all vaccine administration policies and procedures.

Before Administering Vaccine

Health care professionals should be knowledgeable about appropriate techniques to prepare and care for patients when administering vaccines.

Assess for Needed Vaccines

The patient’s immunization status should be reviewed at every health care visit. Using the patient’s immunization history, health care providers should assess for all routinely recommended vaccines as well as any vaccines that are indicated based on existing medical condition(s), occupation, or other risk factors.

To obtain a patient’s immunization history, information from immunization information systems (IISs), current and historical medical records, and personal shot record cards may be used. In most cases, health care providers should only accept written, dated records as evidence of vaccination; however, self-reported doses of influenza vaccine or pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) are acceptable.

Missed opportunities to vaccinate should be avoided. If a documented immunization history is not available, administer the vaccines that are indicated based on the patient’s age, medical condition(s), and other risk factors, such as planned travel.

Screen for Contraindications and Precautions

Before administering any vaccine, patients should be screened for contraindications and precautions, even if the patient has previously received that vaccine. The patient’s health condition or recommendations regarding contraindications and precautions for vaccination may change from one visit to the next.

To assess patients correctly and consistently, health care providers should use a standardized, comprehensive screening tool. To save time, some facilities ask patients to answer screening questions before seeing the provider, either electronically via an online health care portal or on a paper form while in the waiting or exam room.

Educate Patients or Parents about Needed Vaccines

Vaccines are one of the safest and most effective ways to prevent diseases. All health care personnel , including non-clinical staff, play an important role in promoting vaccination and creating a culture of immunization within a clinical practice. Inconsistent messages from health care personnel about the need for and safety of vaccines may cause confusion about the importance of vaccines.

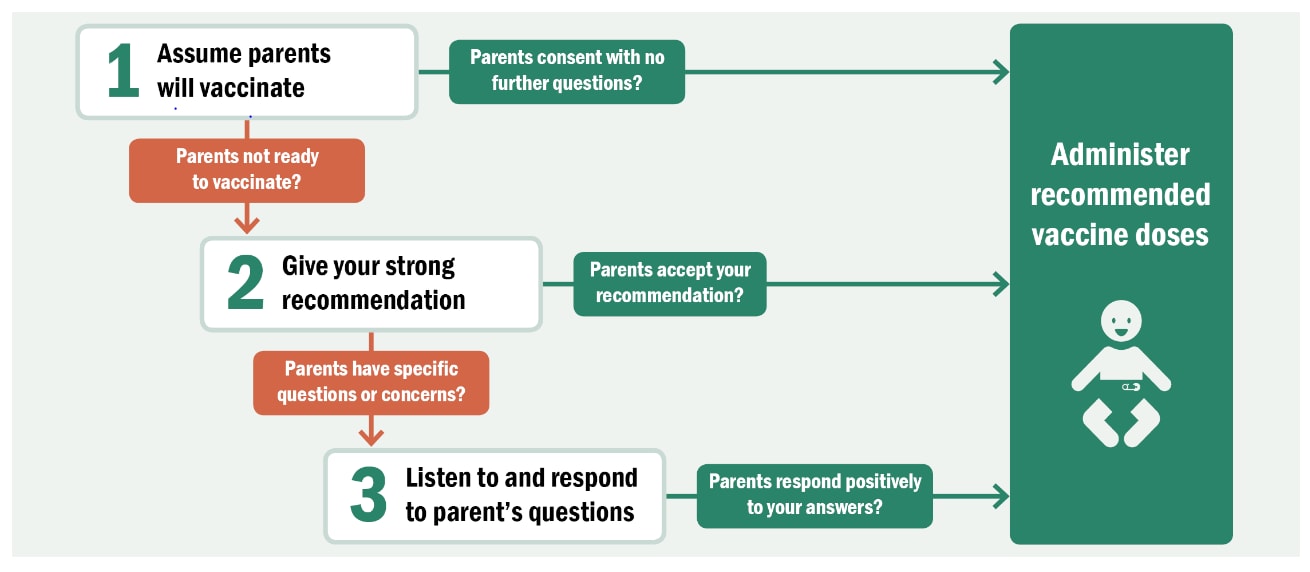

Studies show health care providers are the most trusted source of vaccine information. Research also shows when a strong recommendation is given by a health care provider, a patient is four to five times more likely to be vaccinated. When providers use presumptive language to initiate vaccine discussions, significantly more parents choose to vaccinate their children, especially at first-time visits. Instead of saying “What do you want to do about shots today,” an approach using presumptive language would be to say, “Your child needs three vaccines today.”

Some patients and parents may have questions or concerns about vaccination. This does not necessarily mean they will not accept vaccines. Sometimes they simply want to hear their provider’s answers to their questions.

Health care professionals need to be prepared to answer questions. In addition, many state and local immunization programs and professional organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, have resources. There are numerous strategies for effectively educating and talking to patients and parents about the need to vaccinate.

Vaccine Information Statements (VISs)

Vaccine information statements (VISs) are documents that inform vaccine recipients or their parents about the benefits and risks of a vaccine. Federal law requires VISs be provided when routinely recommended childhood vaccines are administered. Everyone, including adults, should be given the appropriate VIS when receiving a vaccine covered under the law. The VIS must be given:

- Before the vaccine is administered

- Regardless of the age of the person being vaccinated (e.g., when influenza vaccine is given to an adult)

- Every time a dose of vaccine is administered, even if the patient has received the same vaccine and VIS in the past

CDC encourages the use of all VISs, whether the vaccine is covered by the law requiring VIS or not. VISs can be provided at the same time as a screening questionnaire, while the patient is waiting to be seen. They include information that may help the patient or parent respond to the screening questions and can be used by providers during conversations with patients. VISs are available as paper copies and in electronic formats that can be read on smart phones and other devices.

After-Care Instructions

Patient and parent education should also include a discussion of comfort and care strategies after vaccination. After-care instructions should include information for dealing with common side effects such as injection site pain, fever, and fussiness (especially in infants). Instructions should also provide information about when to seek medical attention and when to notify the health care provider about concerns that arise following vaccination. After-care information can be given to patients or parents before vaccines are administered, leaving the parent free to comfort the child immediately after the injection. Pain relievers can be used to treat fever and injection-site pain that might occur after vaccination. In children and adolescents, a non-aspirin-containing pain reliever should be used. Aspirin is not recommended for children and adolescents.

Vaccine Administration

Infection Control

Health care personnel should follow routine infection control procedures when administering vaccines.

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is critical to prevent the spread of illness and disease. Hand hygiene should be performed before vaccine preparation, between patients, and any time hands become soiled (e.g., when diapering). Hands should be cleansed with a waterless, alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water. When hands are visibly dirty or contaminated with blood or other body fluids, they should be washed thoroughly with soap and water.

Gloves

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations have not typically required gloves to be worn when administering vaccines unless the person administering the vaccine is likely to come in contact with potentially infectious body fluids or has open lesions on the hands. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, gloves should be worn when administering intranasal or oral vaccines. If gloves are worn, they should be changed, and hand hygiene should be performed between patients.

Gloves will not prevent needlestick injuries. Any needlestick injury should be reported immediately to the site supervisor, with appropriate care and follow-up given as directed by state and local guidelines.

Vaccine Preparation

Preparing vaccine properly is critical to maintaining the integrity of the vaccine during transfer from the manufacturer’s vial to the syringe and, ultimately, to the patient. CDC recommends preparing and drawing up vaccines just before administration. During preparation:

- Follow strict aseptic medication preparation practices.

- Perform hand hygiene before preparing vaccines.

- Use a designated, clean medication area that is not adjacent to areas where potentially contaminated items are placed.

- Avoid distractions. Some facilities have a no-interruption zone, where health care professionals can prepare medications without interruptions.

- Prepare medications for one patient at a time.

- Always follow the vaccine manufacturer’s directions, located in the package inserts.

Choose the Correct Vaccine

Vaccines are available in different presentations, including single-dose vials (SDV), manufacturer-filled syringes (MFS), multidose vials (MDV), oral applicators, and a nasal sprayer. Always check the label on the vial or box to determine:

- It is the correct vaccine and diluent (if needed).

- The expiration date has not passed. Expired vaccine or diluent should never be used.

Single-Dose Vials (SDV)

Most vaccines are available in SDVs. SDVs do not contain preservatives to help prevent microorganism growth. Therefore, vaccines packaged as SDVs are intended to be punctured once for use in one patient and for one injection. Even if the SDV appears to contain more vaccine than is needed for one patient, it should not be used for more than one patient. Once the appropriate dosage has been withdrawn, the vial and any leftover contents should be discarded appropriately. SDVs with any leftover vaccine should never be saved to combine leftover contents for later use.

Manufacturer-Filled Syringes (MFS)

MFSs are prepared with a single dose of vaccine and sealed under sterile conditions by the manufacturer. Like SDVs, MFSs do not contain a preservative to help prevent the growth of microorganisms. MFSs are intended for one patient for one injection. Once the sterile seal has been broken, the vaccine should be used or discarded by the end of the workday.

Multidose Vials (MDV)

A MDV contains more than one dose of vaccine. MDVs are labeled by the manufacturer and typically contain an antimicrobial preservative to help prevent the growth of microorganisms. Because MDVs contain a preservative, they can be punctured more than once. MDVs used for more than one patient should only be kept and accessed in a dedicated, clean medication preparation area, away from any nearby patient treatment areas. This is to prevent inadvertent contamination of the vial through direct or indirect contact with potentially contaminated surfaces or equipment. Only the number of doses indicated in the manufacturer’s package insert should be withdrawn from the vial. Partial doses from two or more vials should never be combined to obtain a dose of vaccine.

Oral Applicators and Nasal Sprayer

An oral applicator is for use with oral vaccines and contains only one dose of medication. Oral vaccines do not contain a preservative. Rotavirus vaccine is administered using an oral applicator. An intranasal sprayer is used for the live, attenuated influenza vaccine.

Inspect the Vaccine

Each vaccine and diluent (if needed) should be carefully inspected for damage, particulate matter, or contamination before using. Verify the vaccine has been stored at proper temperatures.

Check the Expiration Date of the Vaccine or Diluent

Determining when a vaccine or diluent expires is an essential step in the vaccine preparation process. The expiration date printed on the vial or box should be checked before preparing the vaccine.

- When the expiration date has only a month and year, the product may be used up to and including the last day of that month unless the vaccine was contaminated or compromised in some way.

- If a day is included with the month and year, the product may only be used through the end of that day unless the vaccine was contaminated or compromised in some way.

Beyond-Use Date (BUD)

In some instances, vaccine must be used by a date earlier than the expiration date on the label. This time frame is referred to as the “beyond-use date” (BUD). The BUD supersedes but should never exceed the manufacturer’s expiration date. Vaccines should not be used after the BUD. The BUD should be noted on the label, along with the initials of the person making the calculation. Examples of vaccines with BUDs include:

- Reconstituted vaccines have a limited period for use once the vaccine is mixed with a diluent. This time period is discussed in the package insert.

- Some MDVs vials have a specified period for use once they have been punctured with a needle. For example, the package insert may state the vaccine must be discarded 28 days after it is first punctured.

- Manufacturer-shortened expiration dates may apply when vaccine is exposed to inappropriate storage conditions. The manufacturer might determine the vaccine can still be used but will expire on an earlier date than the date on the label.

Reconstitute Lyophilized Vaccine

Reconstitution is the process of adding a diluent to a dry ingredient to make it a liquid. The lyophilized vaccine (powder or pellet form) and its diluent come together from the manufacturer. Vaccines should be reconstituted according to manufacturer guidelines using only the diluent supplied for a specific vaccine. Diluents vary in volume and composition, and are specifically designed to meet volume, pH balance, and the chemical requirements of their corresponding vaccines. A different diluent, a stock vial of sterile water, or normal saline should never be used to reconstitute vaccines. If the wrong diluent is used, the vaccine dose is not valid and must be repeated using the correct diluent. Vaccine should be reconstituted just before administering by following the instructions in the vaccine package insert.

Once reconstituted, the vaccine should be administered within the time frame specified for use in the manufacturer’s package insert; otherwise, the vaccine should be discarded. Changing the needle between preparing and administering the vaccine is not necessary unless the needle is contaminated or damaged.

Choose the Correct Supplies to Administer Vaccines by Injection

OSHA requires that safety-engineered injection devices (e.g., needle-shielding syringes or needle-free injectors) be used for injectable vaccines in all clinical settings to reduce the risk of needlestick injury and disease transmission. General guidance when selecting supplies to administer a vaccine by injection includes:

- Inspect the packaging; never use supplies with torn or compromised packaging.

- Some syringes and needles are packaged with an expiration date. If present, check the expiration date. Never use expired supplies.

- Use a separate syringe and needle for each injection. Never administer a vaccine from the same syringe to more than one patient, even if the needle is changed.

Syringe Selection

An injectable vaccine may be administered in either a 1-mL or 3-mL syringe.

Needle Selection

Vaccines must reach the desired tissue to provide an optimal immune response and reduce the likelihood of injection-site reactions. A supply of needles should be available in varying lengths appropriate for the facility’s patient population. Clinical judgment should be used when selecting needle length. Needle selection should be based on the:

- Route of administration

- Patient age

- Gender and weight (for adults age 19 years or older)

- Injection site

- Injection technique

Needle Length and Gauge for Subcutaneous Injection

| Age and Gender | Needle Length and Gauge | Injection Site |

|---|---|---|

| All ages and both genders | 5/8-inch (16 mm): 23- to 25-gauge | Thigh for infants younger than age 12 months*; upper outer triceps area for persons age 12 months and older |

Needle Length and Gauge: Children and Adolescents (birth – 18 years) for Intramuscular Injection

| Age and Gender | Needle Length and Gauge | Injection Site |

|---|---|---|

| Neonate, 28 days or younger | 5/8-inch (16 mm)*: 22- to 25-gauge | Vastus lateralis muscle of anterolateral thigh |

| Infants, 1–12 months | 1-inch (25 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Vastus lateralis muscle of anterolateral thigh |

| Toddlers, 1–2 years | 1- to 1.25-inch (25–32 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Vastus lateralis muscle of anterolateral thigh (preferred site) |

| 5/8*- to 1-inch (16–25 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Deltoid muscle of arm | |

| Children, 3–10 years | 5/8*- to 1-inch (16–25 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Deltoid muscle of arm (preferred site) |

| 1- to 1.25-inch (25–32 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Vastus lateralis muscle of anterolateral thigh | |

| Children, 11–18 years | 5/8*- to 1-inch (16–25mm): 22- to 25-gauge | Deltoid muscle of arm (preferred site) † |

†The vastus lateralis muscle of the anterolateral thigh can also be used. Most adolescents and adults will require a 1- to 1.5-inch (25–38 mm) needle to ensure intramuscular administration.

Needle Length and Gauge: Adults (age 19 years or older) for Intramuscular Injection

| Age and Gender | Needle Length and Gauge | Injection Site |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 130 lbs (60 kg) | 1-inch (25 mm)*: 22- to 25-gauge | Deltoid muscle of arm (preferred site)† |

| 130–152 lbs (60–70 kg) | 1-inch (25 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | |

| Men, 153–260 lbs (70–118 kg) | 1- to 1.5-inch (25–38 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | |

| Women, 153–200 lbs (70–90 kg) | 1- to 1.5-inch (25–38 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | |

| Men, greater than 260 lbs (118 kg) | 1.5-inch (38 mm): 22- to 25-gauge | |

| Women, greater than 200 lbs (90 kg) | 1.5-inch (38 mm): 22- to 25-gauge |

†The vastus lateralis muscle of the anterolateral thigh can also be used. Most adolescents and adults will require a 1- to 1.5-inch (25–38 mm) needle to ensure intramuscular administration.

Filling Syringes

Standard medication preparation guidelines should be followed for drawing a dose of vaccine into a syringe. The cap on the top of an unopened vaccine vial functions as a dust cover. However, not all vaccine manufacturers guarantee the tops of unused vials are sterile, and the way the cover over the stopper is removed can potentially contaminate the stopper. Therefore, using friction and a sterile alcohol swab to wipe the stopper may help assure aseptic technique. Alcohol evaporates quickly and will dry while the needle is being prepared for insertion into the vial.

Instilling air into a multidose vial prior to withdrawing a vaccine dose is not necessary. It could cause a “spritz” of vaccine to be lost the next time the vial is entered, which, over time, can decrease the amount of vaccine in the vial and lead to the loss of a dose (e.g., only nine full doses in a 10-dose vial).

Before withdrawing each dose, the vial should be agitated to mix the vaccine thoroughly and obtain a uniform suspension. The vaccine should be visually inspected for discoloration and precipitation or to see if it cannot be resuspended before administration. If problems are noted, the vaccine should not be administered.

When filling a syringe:

- Never enter a vial with a previously used syringe or needle.

- Never mix different vaccine products in the same syringe.

- Never transfer vaccine from one syringe to another.

- Never combine partial doses from separate vials to obtain a full dose.

Once the syringe is filled, label it with the name of the vaccine in the syringe. Often more than one vaccine is administered at the same visit and, once drawn into a syringe, vaccines look similar. By labeling the syringe, health care providers will know the route to use to administer the vaccine correctly.

Predrawing Vaccine

Vaccines should be drawn just before administration. However, while MFSs are recommended for large vaccination clinics, there may be rare instances when the only option is to predraw vaccine for off-site clinics.

Procedural Pain Management

Vaccinations are the most common source of procedural pain for healthy children and can be a stressful experience for persons of any age. It has been estimated that up to 25% of adults have a fear of needles, with most needle fears developing during childhood. If not addressed, these fears can have long-term effects such as preprocedural anxiety and avoidance of needed health care throughout a person’s lifetime. Fear of injections and needlestick pain are often cited as reasons why children and adults refuse vaccines.

Pain is a subjective phenomenon influenced by multiple factors, including an individual’s age, anxiety level, previous health care experiences, and culture. Although pain from vaccination is to some extent unavoidable, there are some things that parents and health care providers can do to help. Evidence-based pharmacologic, physical, and psychological interventions exist to ease the pain associated with injections. Combining the interventions described below has been shown to improve pain relief.

Inject Vaccines Rapidly Without Aspiration

Aspiration is not recommended before administering a vaccine. Aspiration prior to injection and injecting medication slowly are practices that have not been evaluated scientifically. Aspiration was originally recommended for theoretical safety reasons and injecting medication slowly was thought to decrease pain from sudden distention of muscle tissue. Aspiration can increase pain because of the combined effects of a longer needle-dwelling time in the tissues and shearing action (wiggling) of the needle. There are no reports of any person being injured because of failure to aspirate.

The veins and arteries within reach of a needle in the anatomic areas recommended for vaccination are too small to allow an intravenous push of vaccine without blowing out the vessel. A 2007 study from Canada compared infants’ pain response using slow injection, aspiration, and slow withdrawal with another group using rapid injection, no aspiration, and rapid withdrawal. Based on behavioral and visual pain scales, the group that received the vaccine rapidly without aspiration experienced less pain. No immediate adverse events were reported with either injection technique.

Inject Vaccines that Cause the Most Pain Last

Many persons receive two or more injections at the same clinical visit. Some vaccines cause more pain than others during the injection. Because pain can increase with each injection, the order in which vaccines are injected matters. Some vaccines cause a painful or stinging sensation when injected; examples include measles, mumps, and rubella; pneumococcal conjugate; and human papillomavirus vaccines. Injecting the most painful vaccine last when multiple injections are being administered can decrease the pain associated with the injections.

Breastfeed Children Age 2 Years or Younger During Vaccine Injections

Mothers who are breastfeeding should be encouraged to breastfeed children age 2 years or younger before, during, and after vaccination. Several aspects of breastfeeding are thought to decrease pain by multiple mechanisms: being held by the parent, feeling skin-to-skin contact, suckling, being distracted, and ingesting breast milk. Potential adverse events such as gagging or spitting up have not been reported. Alternatives to breastfeeding include bottle-feeding with expressed breast milk or formula throughout the procedure, which simulates aspects of breastfeeding.

Give a Sweet-Tasting Solution to Children Who Are Not Breastfed

Children (age 2 years or younger) who are not breastfed during vaccination may be given a sweet-tasting solution such as sucrose or glucose one to two minutes before the injection. The analgesic effect can last for up to 10 minutes following administration and can mitigate vaccine injection pain. Parents should be counseled that sweet-tasting liquids should only be used for the management of pain associated with a procedure such as an injection and not as a comfort measure at home.

Pain Relievers

Topical anesthetics block transmission of pain signals from the skin. They decrease the pain as the needle penetrates the skin and reduce the underlying muscle spasm, particularly when more than one injection is administered. These products should be used only for the ages recommended and as directed by the manufacturer. Because using topical anesthetics may require additional time, some planning by the healthcare provider and parent may be needed. Topical anesthetics can be applied during the usual clinic waiting times, or before the patient arrives at the clinic provided parents and patients have been shown how to use them appropriately. There is no evidence that topical anesthetics have an adverse effect on the vaccine immune response.

The prophylactic use of antipyretics (e.g., acetaminophen and ibuprofen) before or at the time of vaccination is not recommended. There is no evidence these will decrease the pain associated with an injection. In addition, some studies have suggested these medications might suppress the immune response to some vaccine antigens.

Follow Age-Appropriate Positioning Best Practices

For both children and adults, the best position and type of comforting technique should be determined by considering the patient’s age, activity level, safety, comfort, and administration route and site. Parents play an important role when infants and children receive vaccines. Parent participation has been shown to increase a child’s comfort and reduce the child’s perception of pain. Holding infants during vaccination reduces acute distress. Skin-to-skin contact for infants up to age 1 month has been demonstrated to reduce acute distress during the procedure.

A parent’s embrace during vaccination offers several benefits. A comforting hold:

- Avoids frightening children by embracing them rather than overpowering them

- Allows the health care professional steady control of the limb and the injection site

- Prevents children from moving their arms and legs during injections

- Encourages parents to nurture and comfort their child

A combination of interventions, holding during the injection along with patting or rocking after the injection, is recommended for children up to age 3 years. Parents should understand proper positioning and holding for infants and young children. Parents should hold the child in a comfortable position, so that one or more limbs are exposed for injections.

Research shows that children age 3 years or older are less fearful and experience less pain when receiving an injection if they are sitting up rather than lying down. The exact mechanism behind this phenomenon is unknown. It may be that the child’s anxiety level is reduced, which, in turn, reduces the child’s perception of pain.

Tactile Stimulation

Moderate tactile stimulation (rubbing or stroking the skin) near the injection site before and during the injection process may decrease pain in children age 4 years or older and in adults. The mechanism for this is thought to be that the sensation of touch competes with the feeling of pain from the injection and, thereby, results in less pain.

Route and Site for Vaccination

The recommended route and site for each vaccine are based on clinical trials, practical experience, and theoretical considerations. There are five routes used to administer vaccines. Deviation from the recommended route may reduce vaccine efficacy or increase local adverse reactions. Some vaccine doses are not valid if administered using the wrong route, and revaccination is recommended.

Oral Route (PO)

Oral vaccines should generally be administered before injectable vaccines. Rotavirus vaccines (RV1 [Rotarix], RV5 [RotaTeq]) are administered orally. Because the two brands of rotavirus vaccine are prepared differently and have different types of oral applicators, health care professionals should be familiar with how to prepare and administer the brand stocked in their facility. Rotavirus vaccine should never be injected.

To administer rotavirus vaccine:

- Perform proper hand hygiene. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, gloves should be worn.

- Administer the liquid vaccine slowly against the inside of the infant’s cheek (between the cheek and gum) toward the back of the infant’s mouth. Never administer the vaccine directly into the throat. This can increase the chance that the infant will cough or gag and spit out the vaccine rather than swallowing it.

- Allow the infant time to swallow.

- Care should be taken to avoid triggering the gag reflex.

An infant can eat or drink immediately before or after administration of either product. The dose does not need to be repeated if an infant regurgitates, spits out the vaccine, or vomits during or after administration. No data exist on the benefits or risks associated with readministering a dose of rotavirus vaccine. The infant should receive the remaining recommended doses of rotavirus vaccine following the routine schedule.

Intranasal Route (NAS)

Live, attenuated influenza (LAIV [FluMist]) vaccine is administered by the intranasal route. LAIV is administered into each nostril using a manufacturer-filled nasal sprayer. A dose-divider clip, located on the plunger, separates the total vaccine dose of 0.2 mL into two equal parts of 0.1 mL each. LAIV should never be injected. The patient should be seated in an upright position and instructed to breathe normally. The provider should gently place a hand behind the patient’s head to prevent inadvertent movement.

To administer the vaccine:

- Perform proper hand hygiene. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, gloves should be worn.

- Remove the rubber tip of the nasal sprayer and place the tip of the applicator just inside the patient’s nostril.

- Push the plunger rapidly in a single motion until the dose-divider clip is reached.

- Pinch and remove the dose-divider clip.

- Place the tip of the applicator just inside the other nostril and repeat the process to administer the remaining vaccine.

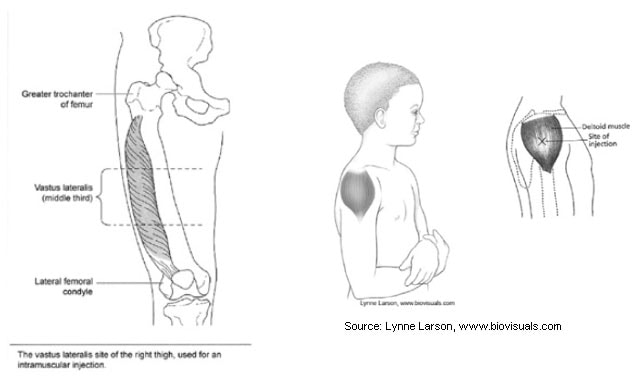

Source: Lynne Larson, www.biovisuals.com

The dose does not need to be repeated if the patient coughs, sneezes, or expels the dose in any other way.

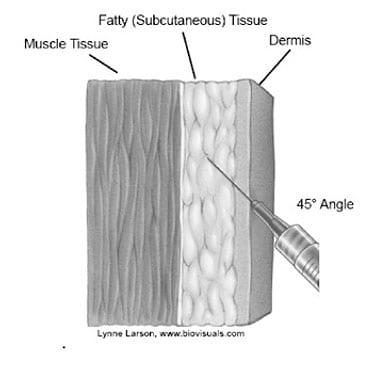

Subcutaneous Route (Subcut)

Routinely recommended vaccines administered by subcutaneous injection include MMR (MMR-II), VAR (Varivax), IPV (IPOL), MMRV (ProQuad), and PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23). IPOL and Pneumovax 23 can be administered by intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous injection.

Subcutaneous injections are administered into the fatty tissue found below the dermis and above muscle tissue. For infants younger than age 12 months, a subcutaneous injection is usually administered into the fatty tissue of the thigh, although the upper outer triceps area of the arm may be used if necessary. For persons age 1 year or older, subcutaneous injections are given in the fatty tissue above the upper outer triceps of the arm.

Source: California Department of Public Health

When administering a vaccine subcutaneously:

- Perform proper hand hygiene.

- Cleanse the skin with a sterile alcohol swab and allow it to dry.

- Pinch up the skin and underlying fatty tissue.

- Insert the needle at a 45-degree angle into the subcutaneous tissue and inject the vaccine. Avoid reaching the muscle.

- Withdraw the needle.

- Apply an adhesive bandage to the injection site if there is any bleeding.

Intradermal Injection

No routinely recommend U.S. vaccines are administered by the intradermal route of injection.

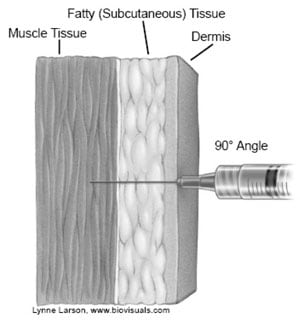

Intramuscular Route

Source: California Department of Public Health

Routinely recommended vaccines administered by IM injection include:

- DT

- DTaP (Daptacel, Infanrix)

- DTaP-IPV-HepB (Pediarix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- DTaP-IPV (Kinrix, Quadracel)

- Hib (PedvaxHIB, ActHIB, Hiberix)

- HepA (Havrix, Vaqta)

- HepB (Engerix B, Recombivax HB)

- HepB-CpG (Heplisav-B)

- HepA-HepB (Twinrix)

- HPV (Gardasil 9)

- IIV (multiple brands)

- IPV (IPOL)

- MenACWY (Menactra, MenQuadfi, Menveo)

- MenB (Bexsero, Trumenba)

- PCV13 (Prevnar 13)

- PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23)

- RZV (Shingrix)

- Td (Tenivac, Tdvax)

- Tdap (Adacel, Boostrix)

Source: Lynne Larson, www.biovisuals.com

IPOL and Pneumovax 23 can be administered by IM or subcut injection.

IM injections are administered into the muscle through the skin and subcutaneous tissue. There are only two recommended sites for administering vaccines by IM injection:

- Vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral thigh

- Deltoid muscle in the upper arm

Injection at these sites reduces the chance of involving neural or vascular structures. The preferred site depends on the patient’s age, weight, gender, and the degree of muscle development.

When administering an IM injection:

- Perform proper hand hygiene.

- Identify the appropriate landmarks for the site.

- Cleanse the skin with a sterile alcohol swab and allow it to dry.

- Spread the skin tight to isolate the muscle. Another acceptable technique for pediatric and geriatric patients is to grasp the tissue and “bunch up” the muscle.

- Insert the needle at a 90-degree angle and inject the vaccine.

- Withdraw the needle.

- Apply an adhesive bandage to the injection site if there is any bleeding.

Site Recommendations for Intramuscular Vaccination

For both sites, an IM injection ideally should be administered into the middle of the muscle where the muscle tissue is thickest.

Infants (12 Months or Younger)

For most infants, the vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral thigh is the recommended site for injection because it provides a large muscle mass. The muscles of the buttock are not used for administration of vaccines in infants and children because of concern about potential injury to the sciatic nerve, which has been well-documented after injection of antimicrobial agents into the buttock. If the gluteal muscle must be used (e.g., because of reduced anatomic site availability), care should be taken to define the anatomic landmarks. A gluteal muscle injection should be administered laterally and superior to a line between the posterior superior iliac spine and the greater trochanter or in the ventrogluteal site, the center of a triangle bound by the anterior superior iliac spine, the tubercle of the iliac crest, and the upper border of the greater trochanter.

Toddlers (1 Year through 2 Years)

For toddlers, the vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral thigh is preferred. The deltoid muscle can be used if the muscle mass is adequate.

Source: California Department of Public Health

Children/Adolescents (3 Years through 18 Years)

The deltoid muscle is preferred for children age 3 through 18 years. The vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral thigh is an alternative site if the deltoid sites cannot be used.

Adults (19 Years or Older)

For adults, the deltoid muscle is recommended. IM injections are administered at a 90-degree angle to the skin and, for most adult patients, the skin is spread and the tissues are not bunched. It is acceptable in geriatric patients to grasp the tissue and “bunch up” the muscle. As with children and adolescents, the vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral thigh is an alternative site if the deltoid sites cannot be used.

Multiple Vaccinations

Children and adults often need more than one vaccine at the same time. Giving more than one vaccine at the same clinical visit is preferred because it helps keep patients up-to-date. Use of combination vaccines can reduce the number of injections. Considerations when administering multiple injections include:

- Administer each vaccine in a different injection site. Recommended sites (i.e., vastus lateralis and deltoid muscles) have multiple injection sites. Separate injection sites by 1 inch or more, if possible, so that any local reactions can be differentiated.

- For infants and younger children, if more than two vaccines are being injected into the same limb, the thigh is the preferred site because of the greater muscle mass. For older children and adults, the deltoid muscle can be used for more than one intramuscular injection.

- Vaccines that are the most reactive and more likely to cause an enhanced injection site reaction (e.g., DTaP, PCV13) should be administered in different limbs, if possible.

- Vaccines that are known to be painful when injected (e.g., HPV, MMR) should be administered after other vaccines.

- If both a vaccine and an immune globulin (Ig) preparation are needed (e.g., Td/Tdap and tetanus immune globulin [TIG] or hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin [HBIG]), administer the vaccine in a separate limb from the immune globulin.

Vaccine and Supply Disposal

Immediately after use, all syringe/needle devices should be placed in biohazard containers that are closable, puncture-resistant, leakproof on sides and bottom, and labeled or color-coded. This practice helps prevent accidental needlestick injury and reuse. Used needles should not be recapped or cut or detached from the syringes before disposal.

Empty or expired vaccine vials are considered medical waste and should be disposed of according to state regulations.

Medical waste disposal requirements are set by state environmental agencies. Contact the state or local immunization program or state environmental agency for guidance.

Patient Care after Vaccine Administration

Health care providers should be knowledgeable about the policies and procedures for identifying and reporting adverse events after vaccination. A vaccine adverse event refers to any medical event that occurs after vaccination which may or may not be related to vaccination. Further assessment is needed to determine if an adverse event is caused by a vaccine. An adverse vaccine reaction is an untoward effect caused by a vaccine.

Managing Acute Reactions after Vaccination

Health care providers should be familiar with strategies to prevent and identify adverse reactions after vaccination. Potential life-threatening adverse reactions that can occur immediately after vaccination are severe allergic reactions and syncope (fainting).

Severe Allergic Reactions

Severe, life-threatening anaphylactic reactions following vaccination are rare. Thorough screening for contraindications and precautions prior to vaccination can often prevent reactions. Health care providers should be familiar with identifying immediate-type allergic reactions. Symptoms of immediate-type allergic reactions can include local or generalized urticaria (hives), angioedema, respiratory compromise due to wheezing or swelling of the throat, hypotension, and shock. Health care providers should be competent in treating these events at the time of vaccine administration. All vaccine providers should be certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and be skilled in administering epinephrine. Equipment needed for maintaining an airway should be available for immediate use and the provider should be skilled in using the equipment. Providers should also have a plan in place to contact emergency medical services immediately if there’s an anaphylactic reaction to vaccination, and staff members should know their individual roles in the event of an emergency.

Syncope

All health care professionals who administer vaccines to older children, adolescents, and adults should be aware of the potential for syncope after vaccination and the related risk of injury caused by falls. Appropriate measures should be taken to prevent injuries if a patient becomes weak or dizzy or loses consciousness, including:

- Have the patient seated or lying down for vaccination.

- Be aware of symptoms that precede fainting (e.g., weakness, dizziness, pallor).

- Provide supportive care and take appropriate measures to prevent injuries if such symptoms occur.

- Strongly consider observing patients (seated or lying down) for 15 minutes after vaccination to decrease the risk for injury should they faint.

Reporting an Adverse Event

Health care providers are required by law to report certain adverse events, and encouraged to report other events, following vaccination to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Details on reporting adverse events after vaccination can be found at https://vaers.hhs.gov.

Documenting Vaccinations

Accurate and timely documentation can help prevent administration errors and curtail the number and cost of excess vaccine doses. In addition, preventing excess doses of vaccines may decrease the number of adverse reactions. All vaccines administered should be fully documented in the patient’s permanent medical record. Health care providers who administer vaccines covered by the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (which include all vaccines listed on the ACIP recommended child and adolescent immunization schedule) are required by law to ensure the permanent medical record of the recipient indicates:

- Date of administration

- Vaccine manufacturer

- Vaccine lot number

- Name and title of the person who administered the vaccine and the address of the facility where the permanent record will reside

- The edition date of the VIS distributed and the date it was provided to the patient

Vaccine administration best practices also include documenting the route, dosage, and site. Providers should update a patient’s permanent medical record to reflect any documented episodes of adverse events after vaccination and any serologic test results related to vaccine-preventable diseases (e.g., those for rubella screening or antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen). The patient or parent should be provided with a personal immunization record that includes the vaccination(s) and date administered.

Although there is no national law, it is also important to document when parents or adult patients refuse vaccines despite the vaccine provider’s recommendation. Professional organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and others have developed forms to document when vaccines are refused (https://www.aap.org/en-us/documents/immunization_refusaltovaccinate.pdf).

By age 2 years, more than 20% of the children in the United States typically have seen more than one health care provider, resulting in scattered paper medical records. IISs are confidential, population-based, computerized information systems that collect and consolidate vaccination data from multiple health care providers. Vaccine providers are strongly encouraged to participate in an IIS, and some states mandate documenting vaccinations in an IIS. Laws regarding using an IIS vary by state or region.

Some states’ IISs use bar-coding technology. Implementation of a 2D bar code on vaccine vials and VISs allows for rapid, accurate, and automatic capture of certain data, including the vaccine product identifier, lot number, expiration date, and VIS edition date using a handheld imaging device or scanner that could populate these fields in an IIS and/or an electronic health record.

Vaccine Administration Errors

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention defines a medication error as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.” A preventable event is one that is due to an error that could be avoided. For example, if a patient receives the wrong drug because of look-alike labels between different products, that is considered a preventable event. Vaccines, like other medications, can be involved in errors. Vaccine administration errors can have many consequences, including inadequate immunological protection, possible injury to the patient, cost, inconvenience, and reduced confidence in the health care delivery system.

Common vaccine administration errors include:

- Doses administered too early (e.g., before the minimum age or interval)

- Wrong vaccine (e.g., Tdap instead of DTaP)

- Wrong dosage (e.g., pediatric formulation of hepatitis B vaccine administered to an adult)

- Wrong route (e.g., MMR given by IM injection)

- Vaccine administered outside the approved age range

- Expired vaccine or diluent administered

- Improperly stored vaccine administered

- Vaccine administered to a patient with a contraindication

- Wrong diluent used to reconstitute the vaccine or only the diluent was administered

Traditionally, medication errors are thought to be caused by mistakes. This “blame-seeking” approach fails to address the root cause, potentially causing the error to recur. An environment that values the reporting and investigation of errors (and “near misses”) as part of risk management and quality improvement should be established. Health care personnel should be encouraged to report errors and trust that the situation and those involved will be treated fairly without fear of punishment and ridicule. Error reporting provides opportunities to discover how the errors occur and to share ideas to prevent or reduce those errors in the future. When a vaccine administration error occurs, health care providers should determine how it happened and put strategies in place to prevent it in the future.

Guidance for handling some common vaccine administration errors is included in ACIP’s General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Some vaccine administration errors require revaccination, but others do not.

Vaccine administration errors requiring revaccination include:

- Hepatitis B vaccine administered by any route other than IM injection, or in adults at any site other than the deltoid or anterolateral thigh

- HPV vaccine that is administered by any route other than IM injection

- Influenza vaccine administered subcutaneously

- Any vaccination using less than the appropriate dose (e.g., pediatric formulation hepatitis A vaccine given to an adult) does not count and the dose should be repeated according to age unless serologic testing indicates an adequate response has developed (however, if two half-volume formulations of vaccine are administered on the same clinic day, these 2 doses can count as 1 valid dose)

- If a partial dose of an injectable vaccine is administered because the syringe or needle leaks or the patient jerks away

Vaccine administration errors not requiring revaccination include:

- Any vaccination using more than the appropriate dose (e.g., DTaP administered to an adult) should be counted if the minimum age and minimum interval have been met

- Hepatitis A vaccine and meningococcal conjugate vaccine administered by the subcutaneous route, if the minimum age and minimal interval have been met

- Administering a dose 4 or fewer days earlier than the minimum interval or age is unlikely to have a substantially negative effect on the immune response to that dose. Vaccine doses administered in this 4-day grace period before the minimum interval or age, with a few exceptions, are considered valid. However, state or local mandates might supersede this guideline.

- MMR, varicella, and MMRV administered by IM injection if the minimum age and minimum interval have been met

Acknowledgements

The editors would like to acknowledge Beth Hibbs and Andrew Kroger for their contributions to this chapter.

Selected References

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (ATAGI). Australian Immunization Handbook, Australian Government Department of Health. Canberra; 2018. Accessed October 11, 2020.

- Canadian Government. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide. Accessed October 11, 2020.

- CDC. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization: Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Accessed October 11, 2020.

- CDC. Injection Safety. Accessed October 11, 2020.

- Cohen M. Medication Errors. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Pharmacists Association;2007.

- Harrington J, Logan S, Harwell C, et al. Effective analgesia using physical interventions for infant immunizations. Pediatrics 2012;129(5):815–22.

- Hibbs B, Miller E, Shi J, et al. Safety of vaccines that have been kept outside of recommended temperatures: Reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2008-2012. Vaccine 2018;36(4):553-8.

- Hibbs B, Miller E, Shimabukuro T. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: rotavirus vaccine administration errors–United States, 2006-2013. MMWR 2014;63(4):81.

- Ipp M, Taddio A, Sam J, et al. Vaccine-related pain: randomized controlled trial of two injection techniques. Arch Dis Child 2007;92(12):1105–8.

- Jacobson R, St Sauver J, Griffin J, et al. How health care providers should address vaccine hesitancy in the clinical setting: Evidence for presumptive language in making a strong recommendation. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020;16(9):2131-5.

- Lynn, P. Clinical Nursing Skills: A Nursing Process Approach. 5th ed. Philadelphia PA: Wolters Kluwer;2019.

- Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens: needlesticks and other sharps injuries: Final Rule (29 CFR Part 1910). Fed Regist 2001;66(12):5317–25.

- Opel D, Robinson J, Spielvogle H, et al. Presumptively Initiating Vaccines and Optimizing Talk with Motivational Interviewing’ (PIVOT with MI) trial: a protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of a clinician vaccine communication intervention. BMJ Open 2020;10(8):e039299.

- Moro P, Arana J, Marquez P, et al. Is there any harm in administering extra-doses of vaccine to a person? Excess doses of vaccine reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 2007-2017. Vaccine 2019;37(28):3730-4.

- Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. Board of Health Care Services: Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman J et al., eds. Preventing Medication Errors. Washington DC: National Academies of Sciences;2007.

- Shimabukuro T, Miller E, Strikas R, et al. Notes from the Field: Vaccine Administration Errors Involving Recombinant Zoster Vaccine – United States, 2017-2018. MMWR 2018;67(20):585-6.

- Smith S, Duell D, Martin, B. Clinical Nursing Skills: Basic to Advanced Skills. 8th ed. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.;2011.

- Su J, Miller E, Duffy J, et al. Notes from the Field: Administration Error Involving a Meningococcal Conjugate Vaccine–United States, March 1, 2010-September 22, 2015. MMWR 2016;65(6):161-2.

- Suragh T, Hibbs B, Marquez P, et al. Age inappropriate influenza vaccination in infants less than 6 months old, 2010-2018. Vaccine 2020;38(21):3747-51.

- Taddio A, Appleton M, Bortolussi R, et al. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assc Journal 2010;182:1989-95.

- Taddio A, Ilersich A, Ipp M, et al. Physical interventions and injection techniques for reducing injection pain during routine childhood immunizations systematic review of randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials. Clinical Therapeutics 2009;31(Suppl 2):S48–S76.

- Taddio A, McMurtry C, Shah V, et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAI 2015;187(13):975–82.

- Taylor L, Greeley R, Dinitz-Sklar I, et al. Notes from the Field: Injection Safety and Vaccine Administration Errors at an Employee Influenza Vaccination Clinic—New Jersey, 2015. MMWR 2015;64(49):1363–4.