COVID-19 Science Update released: May 12, 2020 Edition 12

The COVID-19 Science Update summarizes new and emerging scientific data for public health professionals to meet the challenges of this fast-moving pandemic. Weekly, staff from the CDC COVID-19 Response and the CDC Library systematically review literature in the WHO COVID-19 databaseexternal icon, and select publications and preprints for public health priority topics in the CDC Science Agenda for COVID-19 and CDC COVID-19 Response Health Equity Strategy.

Here you can find all previous COVID-19 Science Updates.

PREPRINTS (NOT PEER-REVIEWED)

COVID-19 in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: A case series of 33 patients.external icon Härter et al. medRxiv (May 1, 2020). Publishedexternal icon in Infection (May 11,2020).

Key findings:

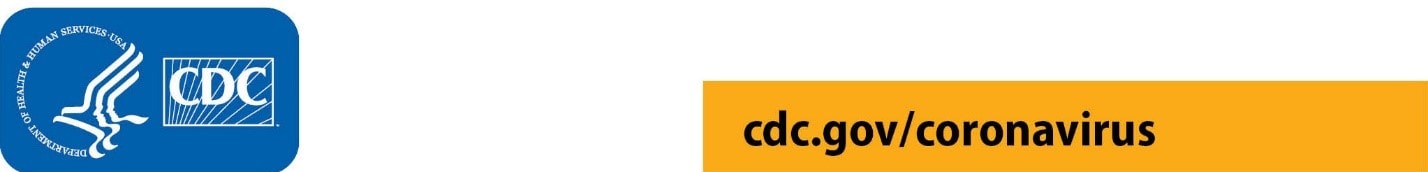

- Among 33 people with HIV (PWH), COVID-19 was mild in 25 (76%), severe in 3 (9%), and critical in 6 (18%) (Figure).

- 30 patients (91%) recovered and 3 (9%) died; all who died had critical COVID-19 and either poorly controlled HIV or multiple comorbidities.

- All patients were on antiretroviral therapy; 31 (94%) were virally suppressed (HIV RNA <50 copies/mL).

- 20 patients (60%) had comorbidities, including hypertension, COPD, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, or renal insufficiency.

Methods: Retrospective analysis of 33 PWH diagnosed with COVID-19 between March 11 and April 17, 2020 in 12 German HIV centers. Disease severity was classified as mild, severe, or critical. Most recent and lowest ever CD4 lymphocyte count, most recent HIV RNA level, current antiretroviral regimen, and comorbidities were recorded. Limitations: Only symptomatic patients were documented; uncontrolled case-series with limited follow-up.

Implications: People with well-controlled HIV generally do not appear to experience excess disease severity or mortality from COVID-19.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Härter et al. COVID-19 severity and outcomes among people with HIV (N = 33). Available under Nature Public Health Emergency Collection via PubMed Central.

Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on Black communitiesexternal icon. Millett et al. medRxiv (May 8, 2020). Published external iconin Annals of Epidemiology (May 14, 2020).

Key findings:

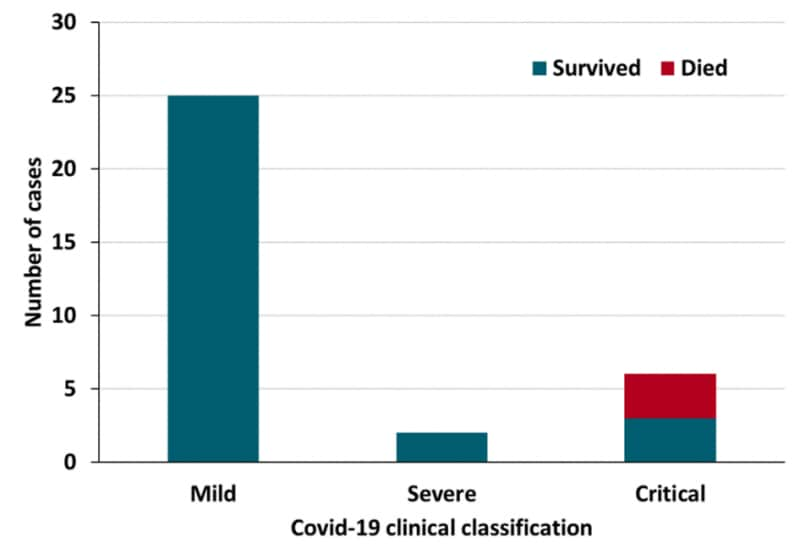

- 97% of US counties with an above average percentage of Black residents (≥13%) had at least one COVID-19 diagnosis compared with 80% of all other US counties.

- US counties with higher a percentage of Black residents had a 23% higher rate of COVID-19 diagnoses and an 18% higher rate of COVID-19-related deaths after adjusting for county-level characteristics such as age, poverty, comorbidities, and epidemic duration (Figure).

Methods: Analysis of COVID-19 cases and deaths in US counties with above average (≥13%) percentage of Black residents compared with all other US counties. Rate ratios were calculated via a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Limitations: Ecological analysis; race/ethnicity of persons diagnosed and who died were unknown and assumed to be represented by county-level overall race/ethnicity profile.

Implications: US counties with a higher percentage of Black residents are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 diagnoses and death.

Figure:

Note: Millett et al. Cumulative COVID-19 deaths comparing US counties with above average percentage of black residents (N=677) and all other US counties (N=2,465). Licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Thromboembolism (TE) is complete or partial obstruction of a blood vessel by a blood clot. Sometimes clots originate in the veins of the leg and may dislodge and travel through the bloodstream to reach the lungs. In other instances, clots can lodge in the heart or brain. Consequences of TE can be serious or life-threatening. TE to the brain, heart, and lungs may result in stroke, heart attack, or respiratory failure, respectively.

PEER-REVIEWED

A. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Lodigiani et al. Thrombosis Research (Apr 23, 2020).

Key findings:

- 7% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients had clots in blood vessels (thromboembolism).

- 8% had lung clots (pulmonary embolism), 2.5% had clots affecting the brain (ischemic stroke), and 1.1% had clots in the heart (acute coronary syndrome/myocardial infarction [ACS/MI]).

- 57% of patients with TE were on preventive treatment at the time of diagnosis; 25% died.

Methods: Study of 388 consecutive patients hospitalized between February 13 and April 10, 2020 with COVID-19 and thromboembolic complications, including venous thromboembolism (VTE), ischemic stroke, and ACS/MI. Limitations: Retrospective study at a single hospital (limited generalizability).

B. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Poissy et al. Circulation (Apr 24, 2020).

Key findings:

- 6% of COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU had lung clots (pulmonary embolism [PE]), reflecting a rate higher than ICU patients overall (6.1%) and ICU patients with influenza (7.5%) during the same time period.

- At the time of PE diagnosis, 91% of patients were receiving prophylactic antithrombotic treatment (heparin) to prevent PE.

Methods: 107 COVID-19 ICU patients with PE during February 27 and March 3, 2020 compared with historical controls (ICU patients overall and ICU patients with influenza) at a hospital in France. Limitations: High prevalence of obesity may have contributed to high rate of PE.

C. Autopsy Findings and Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With COVID-19. Wichman et al. Annals of Internal Medicine (May 6, 2020).

Key findings:

- Autopsy revealed clots in deep leg veins of 7 of 12 patients (58%) in whom thromboembolism was not suspected before death.

- Lung clots (pulmonary emboli) were the direct cause of death in 4 patients (33%).

Methods: Autopsies on the first 12 patients who died from COVID-19 in Hamburg, Germany.

Implications of three studies (Lodigiani et al., Poissy et al., & Wichman et al.): Thromboembolic complications are common with COVID-19 and can be a clinically occult and unrecognized proximal cause of death. Effective prevention strategies for hospitalized and ambulatory COVID-19 patients are needed.

Tocilizumab is an immunosuppressive drug that is a humanized monoclonal antibody. Some monoclonal antibodies have anti-inflammatory effects and are used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and other conditions. Because inflammation is an important manifestation of severe COVID-19, studies are being conducted to see if monoclonal antibodies, like tocilizumab, can treat COVID-19.

PEER-REVIEWED

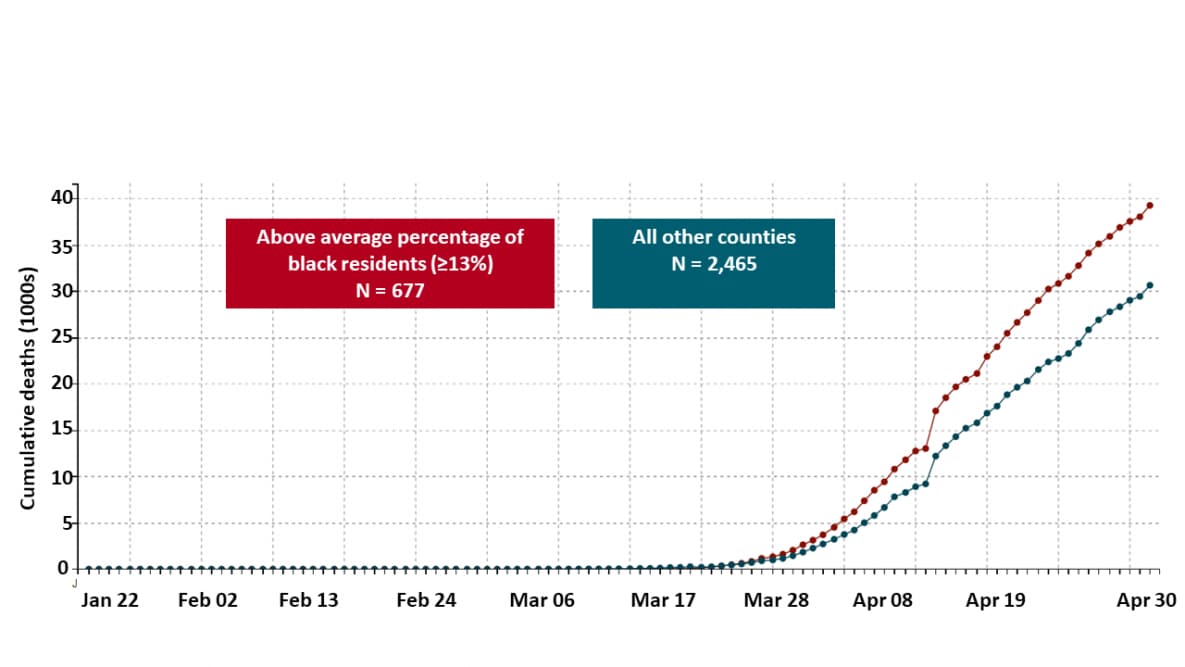

A. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Toniati et al. Autoimmunity Reviews (May 3, 2020).

Key findings:

- 24-72 hours after tocilizumab (TCZ) administration, 58 (58%) of COVID-19 patients requiring ventilatory support showed clinical improvement.

- 10 days after TCZ administration, the condition of 77 (77%) patients had improved and 23 (23%) patients worsened, of whom 20 (20%) died (Figure).

- Levels of inflammatory markers did not correlate with improvement.

- Severe adverse events included septic shock (n = 2, both died) and gastrointestinal perforation (n = 1).

Methods: Consecutive patients diagnosed with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and acute respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support in one hospital in Italy between March 9 and 20, 2020 (N = 100) were given 2 doses of intravenous TCZ (8 mg/kg) 12 hours apart. 13 patients received a third infusion based on clinical response. Patients also received standard therapy. Patient outcomes were analyzed at 24-72 hours and 10 days after receiving TCZ. Limitations: Only patients with severe infections were included; no control group.

B. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicenter study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Sciascia et al. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology (May 1, 2020).

Key findings:

- 14 days after tocilizumab (TCZ) administration, 52 (89%) patients were alive.

- Median levels of some inflammatory markers improved within 1 day of TCZ administration.

- No moderate-to-severe adverse events were reported.

Methods: Patients with severe COVID-19 in four hospitals in Italy (N = 63) were given TCZ intravenously (8 mg/kg) or subcutaneously (324 mg); a second administration within 24 hours was given to 52 patients. Patient outcomes were analyzed at baseline, day 1, 2, 7, and 14. Limitations: No control group.

C. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Xu et al. PNAS (April 14, 2020).

Key findings:

- Within 1 day of tocilizumab (TCZ) administration, fever in all patients (n = 21) resolved.

- Within 5 days of TCZ administration, the respiratory condition of 16 (76%) patients improved.

- All patients were alive and discharged by 3 weeks after TCZ treatment (Figure).

- No serious adverse events were reported.

Methods: Patients diagnosed with severe or critical COVID-19 in two hospitals in China between February 5 and 14, 2020 were given intravenous TCZ (4–8 mg/kg). A second dose was given to 3 patients who still had fever after 12 hours. All had received standard therapy and deteriorated clinically before TCZ. Outcomes were assessed daily for 5 days after receiving TCZ. Limitations: No control group.

Figure:

Note: Adapted from Toniati et al., Sciascia et al., and Xu et al. Survival and death among patients with severe or critical COVID-19 after tocilizumab treatment in two studies from Italy (Toniati et al. & Sciascia et al.) and one study from China (Xu et al.). Sciascia et al. used by permission from author. Xu et al. licensed under CC BY 4.0. Toniati et al. was published in Autoimmunity Reviews, Vol 19, Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy, Page 102568, Copyright Elsevier 2020. This article is currently available at the Elsevier COVID-19 resource center: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-centerexternal icon

Implications of 3 studies (Toniati et al., Sciascia et al., & Xu et al.): Preliminary data suggest improved survival among patients with severe or critical COVID-19 treated with TCZ. Larger randomized clinical trials are needed, and underway, to assess the potential utility and efficacy of TCZ for treatment of patients with severe or critical COVID-19.

Use of personal protective equipment (PPE) − including respirators, masks, eye protection, gowns, and gloves − by health care workers (HCWs) is important to prevent transmission of infection to HCWs and patients. To be effective, respirators and eye protection need to fit tightly to the face. The COVID-19 pandemic requires use of PPE during all patient care, and effects from this prolonged use are being seen.

PEER-REVIEWED

A. Nasal pressure injuries during the COVID-19 epidemicexternal icon. Dell’Era et al. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal (April 30, 2020).

Key findings:

- 35-year-old ICU physician wearing an N95 respirator continuously several hours a day for 7 days developed pain, swelling, and redness at the point of contact between the respirator and nose. Examination showed abrasion and a nasal pressure injury (Figure).

Methods: Case report of an ICU health care provider. Limitations: Single case; no information on rate of nasal pressure injuries.

Figure:

Note: from Dell’Era et al. Nasal pressure injury from extended wearing of an N95 respirator. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

B. Headaches associated with personal protective equipment – A cross-sectional study among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19external icon. Ong et al. Headache (March 30, 2020).

Key findings:

- Healthcare workers (HCWs) used personal protective equipment (PPE), consisting of N95 respirators and eye protection (Figure 2), an average of 18.0 days per month, 5.7 hours a day.

- 81% of HCWs reported PPE-associated headaches with discomfort in areas of contact with PPE.

- Most described headache as bilateral pressure or heaviness within 60 minutes of putting on PPE, which resolved within 30 minutes of removing PPE.

- One-quarter HCWs had associated migraine symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, light sensitivity, neck discomfort, or movement sensitivity.

Methods: Self-administered survey of 158 healthcare workers in Singapore during February 26–March 8, 2020. Limitations: Recall bias; pre-disposing factors, such as stress and sleep disturbance, may have contributed to headaches.

Figure 2

Note: From Ong et al. Views of health care worker wearing N95 respirator, face mask, goggles, and face shield. Used by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ©American Headache Society.

Implications of both studies (Dell’Era et al. & Ong et al.): Among healthcare workers, personal protective equipment can cause discomfort and injury, which may discourage proper use and decrease effectiveness.

PEER-REVIEWED

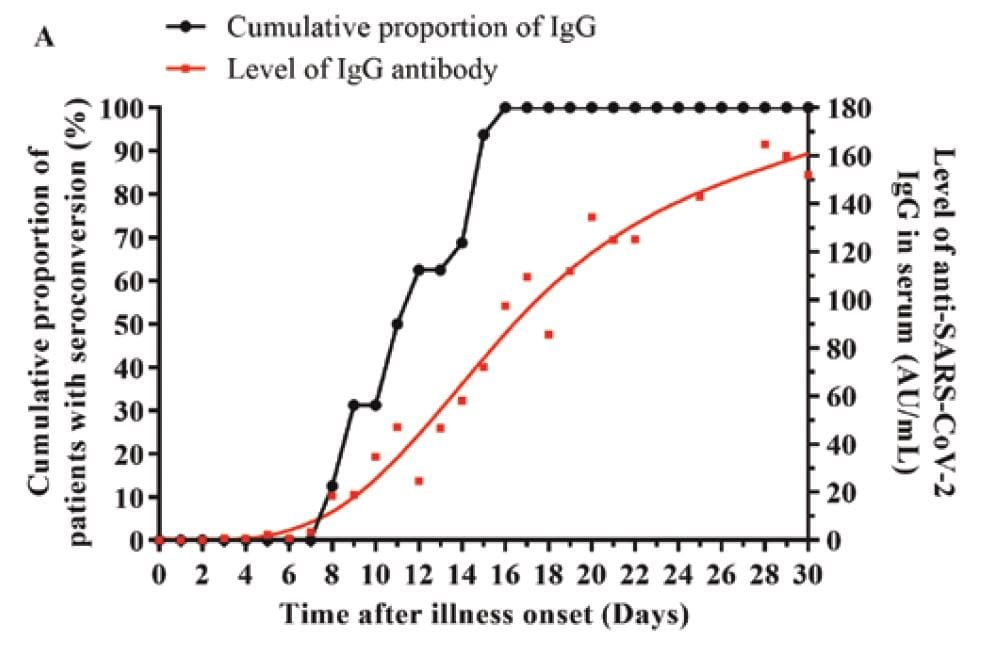

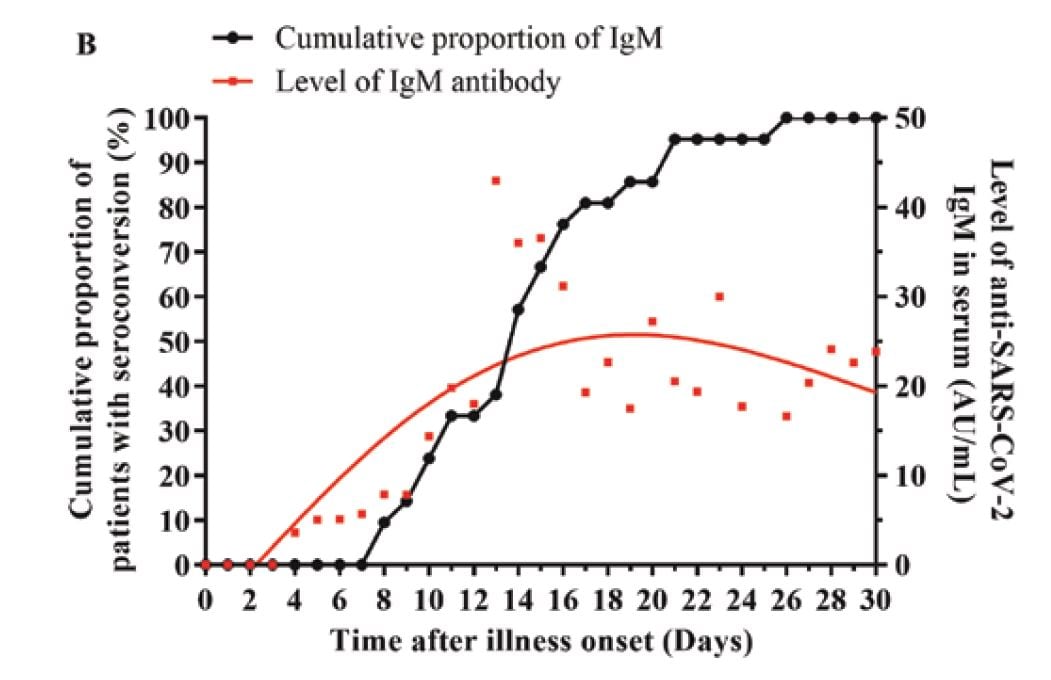

Profile of IgG and IgM antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Qu et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases (27 April 2020).

Key findings:

- IgG and IgM antibodies were detected in 40 (97.6%) and 36 (87.8%) of patients, respectively.

- Median time to detection: IgG (11 days, range 8-16) and IgM (14 days, range 8-28).

- IgG was still rising on day 30 (Figure A); IgM peaked on day 18 and then declined (Figure B).

- Critically ill patients had delayed, but stronger, antibody responses than those with less severe illness.

- No control patients tested positive for antibodies.

Methods: Serologic testing of 347 serum specimens from 41 hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19, between January 11 and February 10, 2020 in Wuhan, China; 5-31 samples per patient collected 3-43 days after onset of illness. Control serum collected from 10 influenza and 28 healthy patients in February 2020. Limitations: Small sample; only COVID-19 patients who required hospitalization; timing and the number of specimens per patient not standardized; about half of tests were positive from the first sample after symptom onset (median 8 days), so earlier seroconversion was not recorded.

Implications: IgG generally appeared earlier and persisted longer than IgM. Further research on the course of antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 is needed.

Figure:

Note: from Qu et al. Level of and cumulative proportion of patients with IgG (A) and IgM (B) antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 among hospitalized patients.

Available via Oxford University Press Public Health Emergency Collection through PubMed Central.

- Stanford et al. Routine screening for HIV in an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemicexternal icon. AIDS & Behavior. An emergency department in Chicago maintained high levels of routine HIV screening and identified new HIV cases, including acute infection, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Curtis et al. Considering BCG vaccination to reduce the impact of COVID-19external icon. Lancet. Lead investigators of 2 BCG vaccine clinical trials in Australiaexternal icon and Netherlands external iconexplain how the BCG vaccine may protect against severe COVID-19.

- Hegarty et al. COVID-19 and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin: What is the link?external icon European Urology Oncology. Lead investigators of a US-based BCG clinical trial (BADASexternal icon) show that the incidence of COVID-19 and case fatality rates are lower in countries with an active BCG vaccination program.

- Hatchimonji et al. Trauma does not quarantine: Violence during the COVID-19 pandemicexternal icon. Annals of Surgery. Violence, including gunshot wounds, has persisted in Philadelphia despite orders to stay at home, prompting the development of COVID-19 relevant protocols for trauma centers.

- Torjesen I. COVID-19: Home testing programme across England aims to help define way out of lockdownexternal icon. BMJ. 100,000 randomly selected people from across England will be sent self-sampling kits and asked to take nose and throat swabs that will be tested for SARS-CoV-2.

- Sood et al. Being African American and rural: A double jeopardy from COVID-19external icon. Journal of Rural Health. Rural African American communities may be at a greater risk for COVID-19 infection.

- Bonow et al. Hydroxychloroquine, coronavirus disease 2019, and QT prolongationexternal icon. JAMA Cardiology. Highlights the potential risk of prolonged QT associated with widespread use of hydroxycholorquine with or without azithromycin. This editorial accompanied 2-article JAMA series: Mercuro et alexternal icon. and Bessière et alexternal icon.

- Steinbrook R. Contact tracing, testing, and control of COVID-19 — Learning from Taiwanexternal icon. JAMA. Editor’s note on learning from Taiwan’s experience with contact tracing, testing, and control of COVID-19. This editorial accompanied: Cheng et alexternal icon.

- Berwick D. Choices for the “New Normal”external icon. Opinion piece on choices for the “new normal,” including how to improve the speed of learning, handle ethical dilemmas, protect HCWs, provide virtual care, prepare for future threats, and combat inequity.

- Bauchner et al. Randomized clinical trials and COVID-19: managing expectationsexternal icon. JAMA. With more than 1,000 studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, commentary outlines six points on how clinicians, the public, and politicians should manage expectations on the results.

Disclaimer: The purpose of the CDC COVID-19 Science Update is to share public health articles with public health agencies and departments for informational and educational purposes. Materials listed in this Science Update are selected to provide awareness of relevant public health literature. A material’s inclusion and the material itself provided here in full or in part, does not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the CDC, nor does it necessarily imply endorsement of methods or findings. While much of the COVID-19 literature is open access or otherwise freely available, it is the responsibility of the third-party user to determine whether any intellectual property rights govern the use of materials in this Science Update prior to use or distribution. Findings are based on research available at the time of this publication and may be subject to change.