Fire Fighter Suffers Sudden Cardiac Death During Rural Water Supply Training – Illinois

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2009-01 Date Released: April 2009

SUMMARY

On October 13, 2008, a 24-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (FF) drove a fire department tanker during rural water supply training. After dumping one load of water and refilling the tanker, the FF and a fire fighter cadet returned to the water drop site. En route to the site, a truck pulled out ahead of the tanker. The FF forcibly applied the brakes, causing the tanker to skid and roll into a ditch. The cadet got himself out of the tanker and summoned help to extricate the FF trapped in the tanker. After approximately 5 minutes, the FF was almost extricated when he lost consciousness. The FF had no visible evidence of major trauma. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was begun, an automated external defibrillator (AED) was applied and advised not to shock, and an oral airway was placed. The medical helicopter arrived, and the FF was airlifted to a local hospital. En route to the hospital, a combitube airway was inserted, a cardiac monitor showed asystole, and an intravenous line was placed. The FF’s condition did not improve during the flight, and the helicopter arrived at the hospital’s emergency department where CPR and advanced life support treatment continued. Approximately 67 minutes after his collapse, despite CPR and advanced life support, the FF died. The death certificate and the autopsy completed by the coroner listed “severe coronary artery atherosclerosis” as the cause of death. Given the FF’s underlying coronary artery disease (CAD), the physical stress of crashing the tanker probably triggered a heart attack or a cardiac arrhythmia resulting in his sudden cardiac death.

The NIOSH investigator offers the following recommendations to address general safety and health issues. Had these recommended measures been in place prior to the FF’s collapse, his sudden cardiac death may have been prevented.

- Provide preplacement and annual medical evaluations to fire fighters consistent with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

- Phase in a comprehensive wellness and fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

- Ensure fire fighters are cleared for return to duty by a physician knowledgeable about the physical demands of fire fighting, the personal protective equipment used by fire fighters, and the various components of NFPA 1582.

- Perform an annual physical performance (physical ability) evaluation to ensure fire fighters are physically capable of performing the essential job tasks of structural fire fighting.

INTRODUCTION & METHODS

On October 13, 2008, a 24-year-old male volunteer fire fighter suffered sudden cardiac death after the fire department tanker he was driving crashed during a rural water supply exercise. Despite CPR and advanced life support, the FF died. The United States Fire Administration notified NIOSH of this fatality on October 14, 2008. NIOSH contacted the affected Fire Department on October 22, 2008, to gather additional information and on December 16, 2008, to initiate the investigation. On January 12, 2009, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Team traveled to Illinois to conduct an on-site investigation of the incident.

During the investigation, NIOSH personnel interviewed the following people:

- Fire Chief

- Assistant Chief

- Witnesses

- FF’s father

NIOSH personnel reviewed the following documents:

- Fire Department policies and operating guidelines

- Fire Department training records

- Fire Department annual report for 2008

- Fire Department incident report

- Police report

- Emergency medical service (ambulance) incident report

- Life Flight medical report

- Hospital emergency department records

- Death certificate

- Autopsy report

- Primary care provider medical records

RESULTS OF INVESTIGATION

Training and Experience. The FF had served 2 years as a volunteer with this Fire Department and routinely drove and operated this tanker. From January 1, 2008, to the incident date the FF had driven and operated the tanker under emergency conditions and under training conditions. In September 2008, he had taken a 2-hour practical portion of a required driver training program established by the Fire Department’s insurance carrier. The FF maintained a commercial driver’s license for his regular job as a tandem dump truck driver for a local excavating company. The FF had no previous vehicle crashes while driving emergency vehicles or personally owned vehicles.

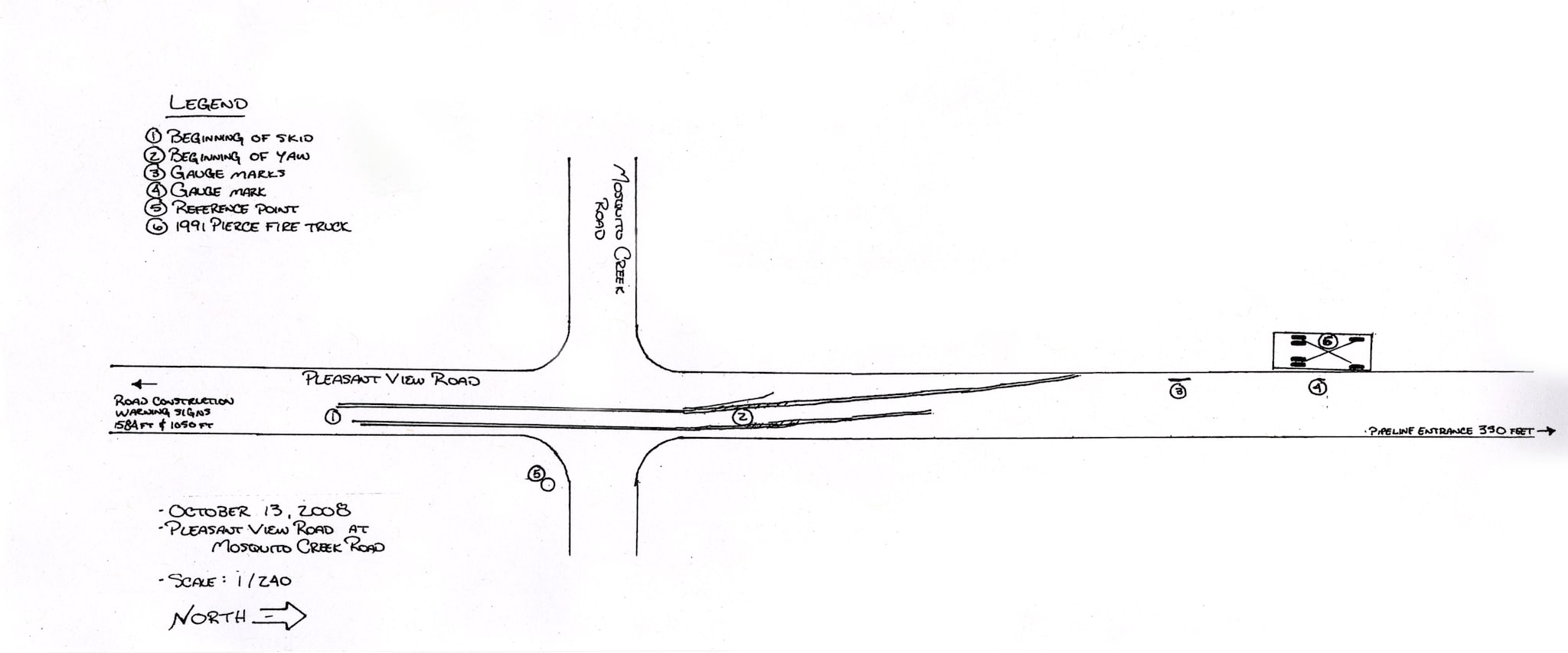

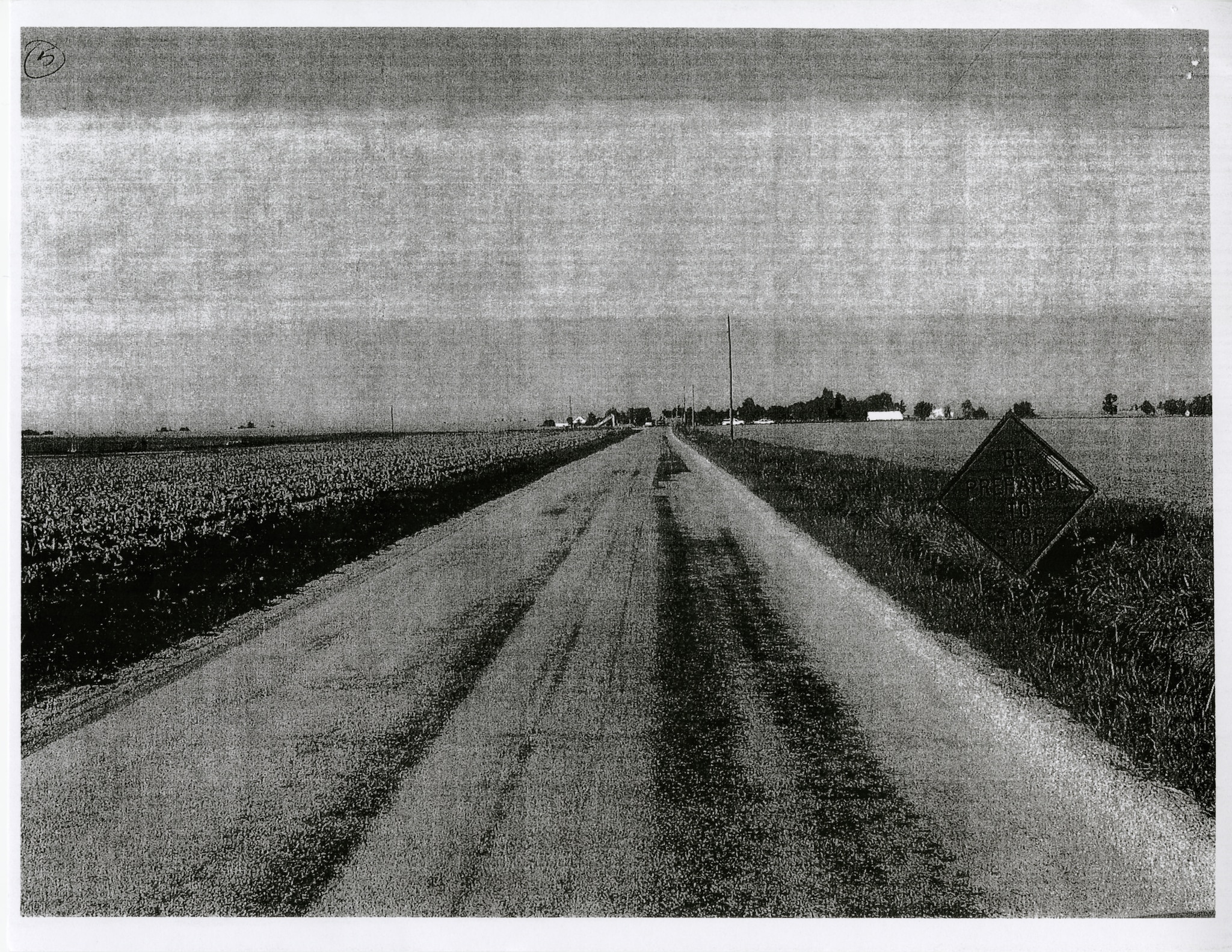

Road and Weather Conditions. The incident occurred on a rural county road approximately 3 miles from the fire station (see Figure 1). The road was polished asphalt with a deteriorating rock chip surface. The road was approximately 18 feet wide at the intersection where the accident occurred. Drainage ditches approximately 1½–2 feet deep were on both sides of the roadway. The road crested 3% prior to the intersection. The sheriff’s office estimated the tanker was travelling no greater than 59 miles per hour (mph); the posted speed limit was 55 mph. On the day of the incident the road was dry and the air temperature was 72°F [NOAA 2008]. The skies were clear, and when the crash occurred at 2024 hours the only natural illumination was moonlight.

Figure1. Police sketch of the tanker’s direction of travel.

Equipment. The tanker truck was a 1991 Pierce Dash 3208, acquired by the Fire Department in 1991. The truck had a diesel engine, two axles, six tires, and an automatic transmission, but did not have an antilock braking system. The truck was custom built by the manufacturer as a water tanker with a 1250 gallon capacity. The design included a baffling system to prevent water from shifting from side to side. The vehicle was equipped with two seats inside the cab and two seats behind the cab, each with combination shoulder and lap seatbelts. The tanker was equipped with an electric siren and a single red light bar mounted on the roof of the cab. When loaded with water, the total truck weight was approximately 41,000 pounds. The tank was filled to capacity at the time of the crash.

A review of the maintenance log (1991–2008) indicated that only minor repairs had been performed on the tanker. According to the driver/operator conducting the most recent inspection, the tires were in good condition and fully inflated. The vehicle’s mileage at the time of the incident was 17,050 miles.

The timeline for this incident with key events includes the following:

- 1830 hours: Training began

- 2024 hours: Tanker crashed

- 2026 hours: Ambulance and Air Evac Life Flight requested

- 2031 hours: FF became unresponsive

- 2036 hours: Approximate time ambulance arrived at the scene

- 2052 hours: Air Evac Life Flight arrived at the scene

- 2105 hours: Air Evac Life Flight departed with the FF en route to the hospital

- 2124 hours: Air Evac Life Flight arrived at the hospital’s emergency department

- 2138 hours: FF pronounced dead

Incident. On October 13, 2008, the Fire Department conducted rural water supply training with two mutual aid fire departments. The training involved tanker trucks from each fire department shuttling water from fire hydrants in town to a drop site (portable tank) 4 miles north and ½ mile west of town. At the drop site, a Fire Department engine was drafting water from the portable tank and projecting a hose stream into an adjacent field at the rate of 250 gallons per minute for 2 hours. The Fire Chief was monitoring activities from this location.

The FF, driving Tanker 38 with a fire fighter cadet, delivered one load of water, dumped it, returned to town, refilled the tanker, and began to return to the portable tank site. At 2024 hours, as Tanker 38 proceeded up a rise in the roadway and approached an intersection at a speed no greater than 59 miles per hour, the cadet saw a pickup truck pull out from a nearby construction site and advised the FF to watch the truck. The FF forcibly applied the brakes, and the tanker began skidding 57 feet prior to entering the intersection (Figure 2). The truck skidded in a relatively straight line over the rise for 112 feet before it began rocking left and right. After skidding an additional 39 feet, the left rear of the truck left the roadway and entered a ditch. This slowed the truck and pulled the truck to the left side of the roadway. The truck continued for another 61 feet before stopping and rolling onto the driver’s side roof, leaving the tanker upside down. The entire crash sequence from beginning (perception) to end was 414 feet. (See Figures 2–5).

Figure 2. Tanker’s direction of travel

Figure 3. Tanker’s final position

Figure 4. Side view of tanker showing damage to the driver’s compartment

Figure 5. Front view of damage to the driver’s compartment

The cadet released his seatbelt, fell to the cab’s ceiling, and climbed out the front windshield. The FF was trapped upside down, yelling for help. The cadet told the FF he was going to summon help. The driver of the pickup truck drove to the scene and called 911 (2026 hours). About this time one of the mutual aid tankers participating in the training happened upon the incident and stopped. After being informed of the situation by the cadet, the mutual aid tanker radioed dispatch for additional help.

The mutual aid crew assessed the FF. He was conscious and conversant, but he could not extricate himself because his head was pinned between the roof and the driver’s seat. The FF did not appear to have any life threatening trauma. He was wearing his seatbelt and was attempting to extricate himself by raising the seat, but this was not successful.

Fire fighters tried to use airbags to raise the tanker enough to free the FF, but this attempt was abandoned because the tanker became unstable. Next, they placed the airbags and cribbing inside the cab to maintain cab stability. At some point, the FF stated that he could not breathe, but nothing visible prevented him from breathing. As the fire fighters inflated the airbags, the FF became unresponsive, stopped breathing, and lost his pulse (approximately 2031 hours). A “sawzall” was then used to cut the steering wheel and the cab’s center post, taking approximately 5 minutes. Fire fighters then moved the driver’s seat enough to free the FF.

The FF was assessed and found to be unresponsive, not breathing, and without a pulse; CPR was begun. The ambulance, staffed with two paramedics, arrived at 2036 hours and assumed patient care. No evidence of trauma was visible, so an oral airway was inserted and rescue breathing was begun. An AED did not reveal a shockable heart rhythm and CPR continued.

At 2052 hours, the Life Flight helicopter arrived and assumed patient care. No evidence of trauma was visible to these paramedics. A cardiac monitor was placed, revealing asystole. Due to copious amounts of secretions and emesis, intubation was not possible. However, a King® airway (oral) was placed and secured. Breath sounds were verified via auscultation and bilateral chest rise. The FF was placed into the helicopter, which departed the scene at 2105 hours en route to the hospital’s emergency department. An intravenous line was placed, and cardiac resuscitation medications were administered. No positive change occurred in the FF’s condition during transport. The helicopter arrived at the hospital at 2124 hours. Inside the emergency department, advanced life support treatment continued until 2138 hours, when the FF was pronounced dead by the attending physician.

Medical Findings. The death certificate and the autopsy completed by the coroner listed “severe coronary artery atherosclerosis” as the cause of death. Findings from the autopsy include no evidence of lethal trauma, some coronary artery atherosclerosis, and mild cardiomegaly. Specific findings from the autopsy report are listed in Appendix A.

The FF was 71 inches tall and weighed 280 pounds, giving him a body mass index (BMI) of 39.0 kilograms per meters squared (kg/m2). A BMI greater than 30.0 kg/m2 is considered obese [CDC 2008]. The FF’s risk factors for CAD included male gender, high blood pressure, and obesity. In 2007, the FF was temporarily prescribed an antihypertensive medication (Toprol XL®) for high blood pressure (140/94 millimeters of mercury [mmHg]) associated with a chronic headache. Shortly thereafter, the medication was stopped, and the FF’s blood pressure remained normal (approximately 130/75 mmHg). He did not report heart-related symptoms (chest pain, chest pressure, angina, shortness of breath on exertion, etc.) to his physician, his family, or the Fire Department.

DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT

At the time of the NIOSH investigation, the volunteer Fire Department consisted of one fire station with 20 uniformed personnel that served a population of 2,000 residents in a geographic area of 70 square miles.

In 2007, the Fire Department responded to 155 calls: 12 building fires, 10 other fires, 91 emergency medical and rescue calls, 2 hazardous condition calls, 21 good intent calls, 10 service calls, 5 severe weather/natural disaster standby calls, 3 false alarms, and 1 other call.

Membership and Training. The Fire Department requires all new fire fighter applicants to be between 18 and 35 years of age; have a valid state driver’s license; and pass a criminal background check, a driving record check, a physical ability test, and an application review by the Fire Chief and the Fire Department officers prior to being appointed by the Fire Chief. New members must provide a certificate of a recent (within 6 months) medical evaluation by a licensed physician, or have the medical evaluation performed by a Fire Department-appointed physician. The new member must then pass a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) test to ensure the member is not claustrophobic. The member is placed on probation for 6 months. The new member must attend weekly training sessions. The State has no minimum requirement for fire fighter certification. The FF was certified as a Driver Operator and a First Responder, and had 2 years of fire fighting experience.

Preplacement Medical Evaluation. Preplacement medical evaluations are required by the Fire Department for all fire fighter candidates. However, the contents of the evaluations vary as the evaluations are performed by the candidate’s primary care physician without input from the Fire Department.

Periodic Medical Evaluations. Annual medical evaluations are not required. However, an annual medical statement is required for all members and is provided to the Fire Department’s insurance carrier.

In September 2007, the FF passed his commercial driver’s license evaluation completed by his primary care physician. An annual SCBA facepiece fit test is required by the Fire Department for interior structural fire fighters, and annual SCBA medical clearance is also required. A Fire Department-appointed physician clears the fire fighter and provides the result to the Fire Department. In March 2008, the FF’s self-completed questionnaire revealed no medical problems. Also at this time, the FF’s evaluation revealed blood pressures of 128/80 mmHg and 136/84 mmHg and normal pulse rates of 82 beats per minute and 92 beats per minute.

Annual physical ability tests are not required. Members injured on duty must be evaluated by their primary care physician, who makes the final determination regarding return to duty.

Health and Wellness Programs. The Fire Department does not have a wellness/fitness program, but exercise (strength and aerobic) equipment is available in the fire station. Health maintenance programs are not available from the city.

DISCUSSION

Coronary Heart Disease and the Pathophysiology of a Heart Attack. In the United States, atherosclerotic CAD is the most common risk factor for cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death [Meyerburg and Castellanos 2008]. Risk factors for its development include age over 45, male gender, family history of CAD, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, obesity/physical inactivity, and diabetes [AHA 2008]. The FF had two of these risk factors (male gender and obesity).

The narrowing of the coronary arteries by atherosclerotic plaques occurs over many years, typically decades [Libby 2008]. However, the growth of these plaques probably occurs in a nonlinear, often abrupt fashion [Shah 1997]. Heart attacks typically occur with the sudden development of complete blockage (occlusion) in one or more coronary arteries that have not developed a collateral blood supply [Fuster et al. 1992]. This sudden blockage is primarily due to blood clots (thromboses) forming on top of atherosclerotic plaques.

Establishing the occurrence of a recent (acute) heart attack requires any of the following: characteristic electrocardiogram (EKG) changes, elevated cardiac enzymes, or coronary artery thrombus. The FF did not have a heartbeat on which to conduct an EKG, cardiac enzymes were not tested, and no thrombus was identified at autopsy. However, occasionally (16%–27% of the time) postmortem examinations do not reveal the coronary artery thrombus/plaque rupture during acute heart attacks [Davies 1992; Farb et al. 1995]. This FF suffered either sudden cardiac death due to an acute heart attack without a thrombus being present at autopsy, or a primary heart arrhythmia (discussed below).

The FF reported no episodes of chest pain (angina) during physical activity (on or off the job), nor during this episode. This lack of chest pain, however, does not rule out a heart attack, because in up to 20% of individuals, the first evidence of CAD may be myocardial infarction or sudden death [Thaulow et al. 1993; Libby 2008].

Epidemiologic studies have found that heavy physical exertion sometimes immediately precedes and triggers the onset of acute heart attacks [Siscovick et al. 1984; Tofler et al. 1992; Mittleman et al. 1993; Willich et al. 1993]. The FF had driven a tanker during a rural water supply exercise. This activity is considered light physical activity [AIHA 1971; Gledhill and Jamnik 1992]. Heart attacks in fire fighters have been associated with alarm response, fire suppression, and heavy exertion during training (including physical fitness training) [Kales et al. 2003; Kales et al. 2007; NIOSH 2007]. The physical stress of driving the fire apparatus probably did not contribute to his sudden death.

Primary Arrhythmia. Because of the lack of definitive evidence of heart attack in this FF, another strong possibility for his sudden cardiac death is a primary cardiac arrhythmia (e.g., ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation). Risk factors for arrhythmias include heart disease, heart attack, dietary supplements, smoking, alcohol, drug abuse, medications, diabetes, and hyperthyroidism [AHA 2009; Mayo Clinic 2009]. The FF’s underlying heart disease (CAD and mild cardiomegaly) was his only risk factor for a primary arrhythmia. The circumstances of this FF’s sudden cardiac death, however, suggest two possible triggering events: (1) blunt chest trauma during the tanker crash, or less likely (2) emotional stress of crashing the tanker.

Blunt Chest Trauma. Nonpenetrating trauma to the sternum/precordium, such as during a motor vehicle crash or sporting events, has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias. The arrhythmias are known to occur with and without evidence of heart muscle contusions (bruises) [Robert 2000; Orliaguet 2001]. The FF had blunt trauma to his chest as evidenced by his broken ribs and sternum at autopsy; however, the forensic pathologist found no evidence of heart muscle contusion on internal and microscopic examination. Low-energy impact to the precordium resulting in sudden death has been termed commotio cordis [Link 1999; Madias 2007]. Studies suggest a few critical variables for inducing these lethal arrhythmias: impact velocity, impact location, impact in relationship to the cardiac cycle (15 milliseconds before the peak of the T wave), and hardness of the object [Link 1998]. Although most of the lethal arrhythmias appear immediately, some have occurred hours and even days after the trauma [Sakka 2000; Tome 2006].

Emotional Stress. Emotional stress has precipitated angina in people with known CAD, and some studies have reported that episodes of anger have triggered heart attacks [Mittleman 1995; AHA 2009]. However, additional research is needed to determine if acute emotional stress such as that likely experienced by the FF during the tanker crash could trigger heart attacks or life threatening arrhythmias.

Occupational Medical Standards for Structural Fire Fighters. To reduce the risk of sudden cardiac arrest or other incapacitating medical conditions among fire fighters, the NFPA developed NFPA 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments [NFPA 2007a]. This voluntary industry standard provides minimum medical requirements for candidates and current fire fighters.

Physical Fitness Programs for Structural Fire Fighters. NFPA 1583, Standard on Health-Related Fitness Programs for Fire Department Members, establishes the minimum requirements for the development of a health-related fitness and exercise program and health promotion for fire department members involved in emergency operations [NFPA 2008]. Members must be cleared annually for participation in a fitness assessment by the fire department physician and are required to participate in a periodic fitness assessment under the supervision of the fire department health and fitness coordinator [NFPA 2008]. The fitness assessment includes (1) aerobic capacity, (2) body composition, (3) muscular strength, (4) muscular endurance, and (5) flexibility. The exercise and fitness program shall include (1) education, (2) individualized participation, (3) warm-up and cool-down exercise guidelines, (4) aerobic exercise, (5) muscular strength and endurance, (6) flexibility exercise, (7) healthy back exercise, and (8) safety and injury prevention [NFPA 2008].

NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, requires the fire department to develop physical performance requirements for candidates and members who engage in emergency operations [NFPA 2007b]. Members who engage in emergency operations must be annually qualified (physical ability test) as meeting these physical performance standards [NFPA 2007b].

The National Volunteer Fire Council (NVFC) and the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) Health and Wellness Project document titled Health and Wellness Guide was developed to improve health and wellness within the volunteer fire service [USFA 2004]. This guide provides suggestions for successfully implementing a health and wellness program for volunteer fire departments.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The NIOSH investigator offers the following recommendations to address general safety and health issues. Had these recommended measures been in place prior to the FF’s collapse, his sudden cardiac death may have been prevented.

Recommendation #1: Provide preplacement and annual medical evaluations to fire fighters consistent with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

Guidance regarding the content and frequency of these evaluations can be found in NFPA 1582 and in the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF)/International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative [NFPA 2007a; IAFF, IAFC 2000]. However, the Fire Department is not legally required to follow this standard or this initiative. Applying this recommendation involves economic repercussions and may be particularly difficult for small, volunteer fire departments to implement. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, paragraphs A.10.6.4 and A.11.1.1 and the National Volunteer Fire Council Health and Wellness Guide address these issues [NFPA 2007b; USFA 2004].

To overcome the financial obstacle of medical evaluations, the Fire Department could urge current members to get annual medical clearances from their private physicians. Another option is having the annual medical evaluations completed by paramedics and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) from the local emergency medical service (vital signs, height, weight, visual acuity, and EKG). This information could then be provided to a community physician (perhaps volunteering his or her time), who could review the data and provide medical clearance (or further evaluation, if needed). The more extensive portions of the medical evaluations could be performed by a private physician at the fire fighter’s expense (personal or through insurance), provided by a physician volunteer, or paid for by the Fire Department, City, or State. Sharing the financial responsibility for these evaluations between fire fighters, the Fire Department, the City, the State, and physician volunteers may reduce the negative financial impact on recruiting and retaining needed fire fighters. Medical evaluations should occur prior to performing fire suppression duties and/or other physically demanding duties including training.

Recommendation #2: Phase in a comprehensive wellness and fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

Guidance for fire department wellness/fitness programs is found in NFPA 1583, Standard on Health-Related Fitness Programs for Fire Fighters, in the IAFF/IAFC Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative, and in the NVFC’s Health and Wellness Guide [NFPA 2008; IAFF, IAFC 2000; USFA 2004]. Worksite health promotion programs have been shown to be cost effective by increasing productivity, reducing absenteeism, and reducing the number of work-related injuries and lost work days [Stein 2000; Aldana 2001]. Fire service health promotion programs have been shown to reduce CAD risk factors and improve fitness levels, with mandatory programs showing the most benefit [Dempsey et al. 2002; Womack et al. 2005; Blevins et al. 2006]. A recent study conducted by the Oregon Health and Science University reported a savings of over $1 million for each of four large fire departments implementing the IAFF/IAFC wellness/fitness program compared to four large fire departments not implementing a program. These savings were primarily due to a reduction of occupational injury/illness claims with additional savings expected from reduced future nonoccupational healthcare costs [Kuehl 2007]. Given this Fire Department’s structure, the NVFC program might be the most appropriate model. NIOSH recommends a formal, structured wellness/fitness program to ensure all members receive the benefits of a health promotion program.

Recommendation #3: Ensure fire fighters are cleared for return to duty by a physician knowledgeable about the physical demands of fire fighting, the personal protective equipment used by fire fighters, and the various components of NFPA 1582.

Guidance regarding medical evaluations and examinations for structural fire fighters can be found in NFPA 1582 [NFPA 2007a] and in the IAFF/IAFC Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative [IAFF, IAFC 2000]. According to these guidelines, the Fire Department should have an officially designated physician who is responsible for guiding, directing, and advising the members with regard to their health, fitness, and suitability for duty as required by NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program [NFPA 2007b]. The physician should review job descriptions and essential job tasks required for all Fire Department positions and ranks, in order to understand the physiological and psychological demands of fire fighters and the environmental conditions under which they must perform, as well as the personal protective equipment they must wear during various types of emergency operations.

Recommendation #4: Perform an annual physical performance (physical ability) evaluation to ensure fire fighters are physically capable of performing the essential job tasks of structural fire fighting.

NFPA 1500 recommends Fire Department members who engage in emergency operations be annually evaluated and certified by the Fire Department as having met the physical performance requirements identified in paragraph 10.2.3 of the standard [NFPA 2007b].

REFERENCES

AHA [2008]. AHA scientific position, risk factors for coronary artery disease. Dallas, TXexternal icon: American Heart Association. [http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/UnderstandYourRiskofHeartAttack/Understanding-Your-Risk-of-Heart-Attack_UCM_002040_Article.jsp]. Date accessed: August 2008. (Link Updated 1/17/2013)

AHA [2009]. Am I at risk of developing arrhythmias? Dallas, TX: American Heart Association. [www.americanheart.org/print_presenter.jhtml?identifier=562]. Date accessed: March 2009. (Link no longer available 12/6/2012)

AIHA [1971]. Ergonomics guide to assessment of metabolic and cardiac costs of physical work. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 32(8):560–564.

Aldana SG [2001]. Financial impact of health promotion programs: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 15(5):296–320.

Blevins JS, Bounds R, Armstrong E, Coast JR [2006]. Health and fitness programming for fire fighters: does it produce results? Med Sci Sports Exerc 38(5):S454.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) [2008]. BMI – Body Mass Index. [www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/english_bmi_calculator/bmi_calculator.html]. Date accessed: August 2008.

Davies MJ [1992]. Anatomic features in victims of sudden coronary death. Coronary artery pathology. Circulation 85[Suppl I]:I-19–24.

Dempsey WL, Stevens SR, Snell CR [2002]. Changes in physical performance and medical measures following a mandatory firefighter wellness program. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34(5):S258.

Farb A, Tang AL, Burke AP, Sessums L, Liang Y, Virmani R [1995]. Sudden coronary death: frequency of active lesions, inactive coronary lesions, and myocardial infarction. Circulation 92(7):1701–1709.

Fuster V, Badimon L, Badimon JJ, Chesebro JH [1992]. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 326(4):242–250.

Gledhill N, Jamnik VK [1992]. Characterization of the physical demands of firefighting. Can J Spt Sci 17(3):207–213.

IAFF, IAFC [2000]. The fire service joint labor management wellness/fitness initiative. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs.

Kales SN, Soteriades ES, Christoudias SG, Christiani DC [2003]. Firefighters and on-duty deaths from coronary heart disease: a case control study.external icon Environ Health 2(1):14. [www.ehjournal.net/content/2/1/14]. Date accessed: September 10, 2008.

Kales SN, Soteriades ES, Christophi CA, Christiani DC [2007]. Emergency duties and deaths from heart disease among fire fighters in the United States. N Engl J Med 356(12):1207–1215.

Kuehl K [2007]. Economic impact of the wellness fitness initiative. Presentation at the 2007 John P. Redmond Symposium in Chicago, IL on October 23, 2007.

Libby P [2008]. The pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of atherosclerosis. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 1501–1509.

Link MS, Wang PJ, Pandian NG, Bharati S, Udelson JE, Lee MY, Vecchiotti MA, VanderBrink BA, Mirra G, Maron BJ, Estes NA [1998]. An experimental model of sudden death due to low-energy chest-wall impact (commotio cordis). N Engl J Med 338(25):1805–1811.

Link MS, Wang PJ, Maron BJ, Estes NA [1999]. What is commotio cordis? Cardiol Rev 7(5):265–269.

Madias C, Maron BJ, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Estes Iii NA, Link MS [2007]. Commotio cordis. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 7(4):235–245.

Mayo Clinic [2009]. Heart arrhythmiasexternal icon. [http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-arrhythmia/basics/definition/CON-20027707?p=1&DSECTION=all]. Date accessed: March 2009. (Link Updated 1/14/2014)

Meyerburg RJ, Castellanos A [2008]. Cardiovascular collapse, cardiac arrest, and sudden cardiac death. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 1707–1713.

Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ, Muller JE [1993]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. N Engl J Med 329(23):1677–1683.

Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Mulry RP, Tofler GH, Jacobs SC, Friedman R, Benson H, Muller JE [1995]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction onset by episodes of anger. Circulation 92(7):1720–1725.

NFPA [2007a]. Standard on comprehensive occupational medical program for fire departments. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1582.

NFPA [2007b]. Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1500.

NFPA [2008]. Standard on health-related fitness programs for fire fighters. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1583.

NIOSH [2007]. NIOSH alert: preventing fire fighter fatalities due to heart attacks and other sudden cardiovascular events. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2007-133.

NOAA [2008]. Quality controlled local climatological data. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.external icon [http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/ulcd/ULCD?prior=Y]. Decatur, IL. Date accessed: February 2009.

Orliaguet G [2001]. The heart in blunt trauma. Anesthesiology 95(2):544–548.

Robert E, De la Coussaye JE, Aya AG, Bertinchant JP, Polge A, Fabbro-Peray P, Pignodel C, Eledjam JJ [2000]. Mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias induced by myocardial contusion. Anesthesiology 92(4):1132–1143.

Sakka SG, Huettemann E, Giebe W, Reinhart K [2000]. Late cardiac arrhythmias after blunt chest trauma. Intensive Care Med 26(6):792–795.

Shah PK [1997]. Plaque disruption and coronary thrombosis: new insight into pathogenesis and prevention. Clin Cardiol 20 (11 Suppl2):II-38–44.

Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T [1984]. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Engl J Med 311(14):874–877.

Stein AD, Shakour SK, Zuidema RA [2000]. Financial incentives, participation in employer sponsored health promotion, and changes in employee health and productivity: HealthPlus health quotient program. J Occup Environ Med 42(12):1148–1155.

Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Erikssen G, Jorgensen L, Cohn PF [1993]. Initial clinical presentation of cardiac disease in asymptomatic men with silent myocardial ischemia and angiographically documented coronary artery disease (The Oslo Ischemia Study). Am J Cardiol 72(9):629–633.

Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, Forman S, Solomon RE, Knatterud GL, Braunwald E [1992]. Modifiers of timing and possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Phase II (TIMI II) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 20(5):1049–1055.

Tome R, Somri M, Teszler CB, Yanovski B, Gaitini L [2006]. Delayed ventricular fibrillation following blunt chest trauma in a 4-year-old child. Paediatr Anaesth 16(4):484–486.

USFA [2004]. Health and wellness guide. Emmitsburg, MD: Federal Emergency Management Agency; United States Fire Administration. Publication No. FA-267.

Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, Arntz HR, Schubert F, Schroder R [1993]. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 329(23):1684–1690.

Womack JW, Humbarger CD, Green JS, Crouse SF [2005]. Coronary artery disease risk factors in firefighters: effectiveness of a one-year voluntary health and wellness program. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37(5):S385.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Cardiovascular Disease Component located in Cincinnati, Ohio. Tommy Baldwin, MS, led the investigation and coauthored the report. Mr. Baldwin is a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, a National Association of Fire Investigators (NAFI) Certified Fire and Explosion Investigator, an International Fire Service Accreditation Congress (IFSAC) Certified Fire Officer I, and a former Fire Chief and Emergency Medical Technician. Thomas Hales, MD, MPH, provided medical consultation and coauthored the report. Dr. Hales is a member of the NFPA Technical Committee on Occupational Safety and Heath, and Vice Chair of the Public Safety Medicine Section of the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM).

Autopsy Findings

- Sublethal Trauma

- Bilateral rib fractures

- Sternal fracture

- Coronary artery disease

- Severe (80%) focal narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery

- Moderate (60%) focal narrowing of the right coronary artery

- No focal narrowing of the left circumflex coronary artery

- No evidence of a thrombus (blood clot) in the coronary arteries

- Mild cardiomegaly (enlarged heart)(heart weighed 460 grams [g]; predicted normal weight is 418 g (ranges between 316 g and 551 g as a function of sex, age, and body weight) [Silver and Silver 2001]

- No visual evidence of ventricular hypertrophy

- Normal cardiac valves

- No evidence of a pulmonary embolus (blood clot in the lung arteries)

- Blood tests for drugs and alcohol were negative (other than for aspirin)

- Blood test for carbon monoxide revealed a < 1% saturation

- Microscopic examination of the tissue sections confirms the gross pathologic findings and shows mild fatty infiltration of the cardiac septum

REFERENCE

Silver MM and Silver MD [2001]. Examination of the heart and of cardiovascular specimens in surgical pathology. In: Silver MD, Gotleib AI, Schoen FJ, eds. Cardiovascular pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone, pp. 8–9.

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In fiscal year 1998, the Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative. NIOSH initiated the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program to examine deaths of fire fighters in the line of duty so that fire departments, fire fighters, fire service organizations, safety experts and researchers could learn from these incidents. The primary goal of these investigations is for NIOSH to make recommendations to prevent similar occurrences. These NIOSH investigations are intended to reduce or prevent future fire fighter deaths and are completely separate from the rulemaking, enforcement and inspection activities of any other federal or state agency. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the deaths in order to provide a context for the agency’s recommendations. The NIOSH summary of these conditions and circumstances in its reports is not intended as a legal statement of facts. This summary, as well as the conclusions and recommendations made by NIOSH, should not be used for the purpose of litigation or the adjudication of any claim. For further information, visit the program website at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

|

This page was last updated on 06/09/09.