Volunteer Fire Fighter Dies While Lost in Residential Structure Fire- Alabama

Revised on June 27, 2011 to include the attached Appendix.

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2008-34 Date Released: June 11, 2009

SUMMARY

|

|

Incident Scene after Victim Removed |

On October 29, 2008, a 24-year old male volunteer fire fighter (the victim) was fatally injured while fighting a residential structure fire. The victim, one of three fire fighters on scene, entered the residential structure by himself through a carport door with a partially charged 1½-in hose line; he became lost in thick black smoke. The victim radioed individuals on the fireground to get him out. Fire fighters were unable to locate the victim after he entered the structure which became engulfed in flames. The victim was caught in a flashover and was unable to escape the fire. Approximately an hour after the victim entered the structure alone, a police officer looking through the kitchen window noticed the victim’s hand resting on a kitchen counter; the victim was nine feet from the carport door he had entered. The victim was removed from the structure and pronounced dead at the scene by emergency medical services. Key contributing factors identified in this investigation include: fire fighters entering a structure fire without adequate training, insufficient manpower, and lack of an established incident command system.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that fire fighters receive essential training consistent with national consensus standards on structural fire fighting before being allowed to operate at a fire incident

- develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for fireground operations

- ensure that fire fighters are trained to follow the two-in/two-out rule and maintain crew integrity at all times

- ensure that adequate numbers of apparatus and fire fighters are on scene before initiating an offensive fire attack in a structure fire

- ensure that officers and fire fighters know how to evaluate risk versus gain and perform a thorough scene size-up before initiating interior strategies and tactics

- develop, implement, and enforce a written incident management system to be followed at all emergency incident operations and ensure that officers and fire fighters are trained on how to implement the incident management system

- ensure fire fighters are trained in essential self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and emergency survival skills

- ensure that protocols are developed on issuing a Mayday so that fire fighters and dispatch centers know how to respond

- ensure that a properly trained incident safety officer (ISO) is established at structure fires

- ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available at structure fires

- ensure that properly coordinated ventilation is conducted on structure fires

- ensure that driver/pump operators receive adequate training to operate and maintain a water supply to hoselines on the fireground

- ensure that all fire fighters engaged in fireground activities wear the full array of personal protective equipment (PPE) issued to them

- ensure that fire fighters are trained to react to PASS and SCBA low air alarms, and that procedures are developed to properly shut down and secure a SCBA and its PASS device

Additionally, states, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction

- should consider requiring mandatory training for fire fighters

INTRODUCTION

On October 29, 2008, a 24-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (the victim) died in a residential structure fire. On October 30, 2008, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On November 3-7, 2008, two safety and occupational health specialists from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated this incident. The NIOSH investigators interviewed the officers and fire fighters of the volunteer departments involved in this incident and county EMS responders. The investigators also spoke with representatives from the Alabama State Fire College and the Alabama Association of Volunteer Fire Departments. The investigators met with the Deputy State Fire Marshal, sheriff’s office investigator and the County 911 Dispatch Director. NIOSH investigators also reviewed witness statements and photographs of the fireground and dispatch tapes, the victim’s training records, and the coroner’s cause of death notification. The incident site was visited and photographed.

Although the performance of the victim’s SCBA was not considered a factor in this incident, the SCBA was examined by NIOSH’s National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory to determine conformity to the NIOSH approved configuration. A summary of this evaluation is included at the end of this report as an appendix. At the request of the fire department, NIOSH contracted with a personal protective equipment (PPE) expert to evaluate the victim’s PPE.a The expert evaluation concluded that the PPE was extensively damaged due to flame and heat exposures, most of which likely occurred after the victim succumbed to either smoke inhalation or severe burn injuries. It was not possible to identify if any of the PPE damage preceded the fatality, or if improper wearing of the PPE contributed to the ultimately fatal injuries. Where it was possible to identify the manufacturer, style of product, and manufacturing date, the gear appeared to be relatively new and compliant with the latest editions of relevant standards. The expert noted that no protective clothing or equipment would be expected to provide adequate protection in the circumstances of this event in which the victim was possibly exposed to a flashover event and subject to flame and high heat for nearly an hour.

a The PPE evaluation report is available upon request to the NIOSH Division of Safety Research, Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program (Attention: Tim Merinar), 1095 Willowdale Road, MS H1808, Morgantown, WV, 26505, 304-285-5916, Tmerinar@cdc.gov.

FIRE DEPARTMENT

- Station “Alpha” – Victim’s Department. The victim’s volunteer department has one station and is comprised of 21 fire fighters. The department serves a population of approximately 14,000 in a geographical area of 25 square miles.

- Station “Bravo” – Mutual Aid Department. The volunteer department has one station and is comprised of 20 fire fighters. The department serves a rural population in a geographical area of 28 square miles.

- Station “Charlie” – Mutual Aid Department. The volunteer department has one station and is comprised of 18 fire fighters. The department serves a population of approximately 8,000 in an area of about 47 square miles. Note: Bravo Fire Department was dispatched before Charlie Fire Department, but did not respond until after the victim was located.

The victim’s department had no verbal or written standard operating procedures for their members to follow.

TRAINING and EXPERIENCE

The 24 year-old victim had been a volunteer fire fighter with this department for 2 years. The victim had attended documented peer-led training on self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), pump operations, water tactics, and general firefighting. The victim had also completed various online training courses on the incident command system (ICS) and national incident management system (NIMS).

The fire fighter initially operating with the victim had joined the fire department three months prior to the incident with no previous experience. Other fire fighters on scene had completed the same online courses in ICS and NIMS.

Alabama has no state training requirements for volunteer fire fighters. The Alabama State Fire College has a non-mandatory 160-hour volunteer fire fighter certification course.1, 2 Alpha fire department members on scene had not completed this training. The three responding members from Charlie fire department had taken this training.

EQUIPMENT and PERSONNEL

- Station “Alpha” – Victim’s Department

- Alpha Rescue 1 (AR1) with one fire fighter (fire fighter #1)

- Alpha Engine 2 (AE2) with two fire fighters (victim, fire fighter #2)

- Alpha Truck 2 (AT2) with one fire fighter (fire fighter #3)

- Alpha Engine 1 (AE1) with one fire fighter (fire fighter #4)

- Station “Charlie” – Mutual Aid Department

- Charlie Engine 3 (CE3) with fire chief (CFC) and one fire fighter (fire fighter #5)

- Charlie Engine 1 (CE1) with one fire fighter (fire fighter #6)

- Privately Owned Vehicle (POV) with one fire fighter

- Water Supply on scene included:

- AR1 300 gallons (used after last communication with victim)

- AE1 1,000 gallons (arrived after last communication with victim)

- AE2 1,000 gallons

- AT2 1,200 gallons (not used)

- CE1 1,000 gallons (arrived after last communication with victim)

- CE3 3,000 gallons (arrived after last communication with victim)

TIMELINE

The timeline for this incident includes the initial call to the 911 dispatch center at 1301 hours. Only the units directly involved in the operations preceding the incident are discussed in this report. Certain key radio transmissions are summarized in the timeline. All times are approximate. The response, listed in order of arrival, fire conditions and key events, includes:

- 1301 Hours

- 911 dispatch center receives a cellular 911 call for an attic fire in a house with all occupants out

Alpha Fire Department dispatched

- 911 dispatch center receives a cellular 911 call for an attic fire in a house with all occupants out

- 1310 Hours

- AR1 en route

- 1316 Hours (thick black smoke from roof)

- AR1 on scene and states, “smoke coming from roof”

AR1 driver requests Bravo Fire Department to be dispatched - Bravo Fire Department dispatched

- AR1 on scene and states, “smoke coming from roof”

- 1317 Hours

- AE2, operated by the victim, on scene (no en route time available)

County EMS dispatched

- AE2, operated by the victim, on scene (no en route time available)

- 1318 Hours

- Bravo Fire Department dispatched again after no response

- County EMS en route

- Victim possibly requesting his hoseline to be charged

- 1319 Hours (thick black smoke from roof)

- AE1 en route

FF1 advises victim he is charging his line

- AE1 en route

- 1320 Hours

- Sounds like victim states, “…fire getting away in here…”

- 1323 Hours (thick black smoke from roof)

- Charlie Fire Department dispatched after Bravo Fire Department was dispatched twice with no response

Inaudible radio traffic by victim

- Charlie Fire Department dispatched after Bravo Fire Department was dispatched twice with no response

- 1324 Hours

- Sounds like victim yells “I’m hot…Come get me, come get me!”

- 1328 Hours (fire blowing out “A” side windows, front door, and carport entry)

- AT2 on scene (no en route time available)

- AE1 on scene

- 1330 Hours

- CE1 and CE3 en route

County EMS on scene

- CE1 and CE3 en route

- 1333 Hours

- AR1 requested ambulance

- 911 dispatch center advised AR1 that ambulance may be on scene

- AR1 requests second ambulance to be dispatched

- 911 dispatch center requested reason for a second ambulance, with no response

- 1338 Hours (fire visible from doors and “A” and “B” side windows)

- CE3 on scene

- 1339 Hours

- CE1 on scene

- 1356 Hours

- AR1 requested local power company to be contacted

- 1418 Hours

- 911 dispatch center received cellular 911 call from police officer on scene requesting Bravo and Delta Fire Departments be dispatched to the scene to help with a trapped fire fighter

- 1420 Hours

- Victim found and removed from structure

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

The victim was last seen wearing a full array of personal protective clothing and equipment, consisting of turnout gear (coat and pants), helmet, Nomex® hood, gloves, boots, and a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) with an integrated personal alert safety system (PASS). The structural fire fighting gear was compliant with the 2007 edition of NFPA 1971. The victim was equipped with a portable radio, flashlight, and various fire fighter hand tools in his pockets. The heat resistant outer shell, moisture barrier, and insulating thermal lining were all present during the incident and documented during the investigation. The victim was found without his helmet and Nomex® hood on. The victim was also missing a glove, boot, and assigned radio. The face piece appeared to have been melted off of the victim.

STRUCTURE

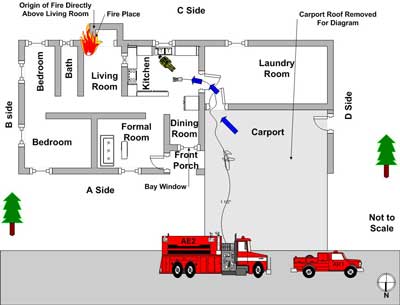

The incident structure was a single-story brick ranch house built in 1969. The residential structure had approximately 2,100 square feet of furnished living area and no basement. The interior construction consisted of wood framing and possibly drywall. The exterior construction was brick with an attached carport at the “A-D” corner (see Diagram). A tin roof had been placed overtop the existing shingled roof.

The origin and cause of the fire was ruled accidental by the Deputy State Fire Marshal and believed to have started in the chimney. The fireplace had been converted into a wood stove with a flue in or around 1970 or 1971. Approximately 8-10 years prior to the incident, the brick chimney had begun to pull away from the house. The owner had wrapped a steel cable around the chimney and placed a turnbuckle to connect the cable ends; this supported the chimney while pulling it back against the house (see Photo 1).

|

|

|

Photo 1. Steel cable used to support the chimney |

|

After the chimney was repositioned, the owner noticed that bricks from the chimney’s flue had cracked and shifted. The owner removed the damaged bricks and replaced them with hollow cinder blocks. These blocks had been laid with the hollows horizontally positioned towards the attic space (see Photo 2). The residents of the house were safely evacuated prior to the fire department’s arrival. The structure was completely destroyed by a rekindle several days later.

|

|

Photo 2. The picture shows the area of the brick chimney flue that was replaced with cinder blocks. The cinder blocks allowed heat and flame to impinge on the exterior wall allowing fire to spread into the attic space. |

WEATHER

The weather at the time of the incident was clear with a temperature of 55°F and slight winds from the west.

INVESTIGATION

On October 29, 2008, at 1301 hours, the 911 dispatch center received a cellular 911 call for an attic fire. The initial dispatch included Station Alpha at 1301 hours, Station Bravo at 1316 hours (no response), and Station Charlie at 1323 hours. Smoke was showing from the roof upon arrival of Station Alpha’s first unit. Incident command was not established by arriving units.

Initial activities of AR1 and AE2

AR1 marked on scene at 1316 hours with thick, black smoke showing from the roof. Fire fighter #1 (FF1) exited the apparatus after he had positioned it in the street in front of the house. He then spoke to several individuals in the yard that had appeared to be exiting away from the house. A female advised him that there was no one left in the house. At 1317 hours the victim and fire fighter #2 (FF2) marked on scene in AE2 and positioned their apparatus behind AR1 (see Diagram). FF1 met the victim and FF2 between their apparatus to put gear on. The victim and FF2 then walked around the house to check on fire conditions. FF1 then flaked out cross-lay #1 (200-ft of 1½-in hose) from AE2. FF2 returned to AE2 to retrieve the hoseline while the victim waited at the A-D corner under the carport. It is believed that the victim and FF2 were on air. FF2 pulled the uncharged cross-lay #1 to the carport door and handed the nozzle to the victim, while FF1 charged the line. The victim opened the bail and water trickled out of the nozzle. The victim yelled back to FF1 to give him more pressure on the hoseline. FF2 recalls hearing the engine of AE2 get really loud, but could not confirm the line being fully charged. The victim and FF2, on air, walked into the structure through the carport door. They were approximately two feet inside the structure and were met by thick, rolling black smoke, but no fire. Quickly, they exited through the carport door taking cross-lay #1 with them. The victim told FF2 to go and get a flashlight. FF2 reported that he told the victim to wait for his return, and that the victim indicated that he would wait.

Activities of FF2

FF2 reported that he walked to the end of the driveway (approximately 75-ft) grabbed the flashlight off of the apparatus, and returned to the carport door. The victim was no longer under the carport, thick black smoke was rolling from the door, and cross-lay #1 was stretched into the structure (see Photo 3). FF2, still on air, entered back into the house through the carport door but could not see his hands or feet just inside the door. He turned the flashlight on and still could not see anything but rolling black smoke. He started yelling the victim’s name and listening for the sound of water flowing or a PASS device. He heard nothing before his low air alarm sounded. Note: FF1 stated his low air alarm sounded after 15-20 minutes of being on air.

|

|

Photo 3. Door under carport that victim entered through. |

Activities of FF1

Moments after FF2 left with the flashlight, FF1 reported hearing the victim radio him and stating, “…at front door, can’t get it opened.” Note: This was not heard on the 911 dispatch tape by NIOSH investigators and is believed to have been on a non-recorded fire department talk around channel. FF1 retrieved an axe from AE2 and donned his SCBA over his bunker gear. He ran to the front porch and found the screen and exterior doors locked. He yanked the screen door off the frame and punched the exterior door open with the head of the axe. He was met with thick black smoke causing him to step back and clean the soot from his face piece. He then stood in the doorway yelling for the victim. FF1 then heard glass breaking from the bay window beside the front door. This window was between the front door and carport (see Photo 4).

|

|

Photo 4. Incident scene after rekindle and collapse |

FF1 thought it was the victim trying to get out. He used the axe and removed the rest of the window pane from the frame. He yelled for the victim again from this window with no response. He then walked off the porch to the carport to see if the victim had come out of the house. He then ran down the D-side to the C-side of the house to look for a back door. During this exterior search, the victim radioed FF1 again, “get me out!” With no available access from C-side, FF1 ran back to the A-side of the house and was met by FF2.

Activities of FF1 and FF2

They both spoke briefly about the victim being lost inside the house. FF2 asked FF1 to assist him in changing his air bottle. After getting his bottle changed, FF2 attempted to get cross-lay #2 (200-ft of 1½-in hose) off AE2 when he noticed the house was “engulfed” in flames. Note: Fire was believed to be pushing out the carport door and A-side bay window. FF1 radioed the 911 dispatch center and requested a second ambulance. Note: The first ambulance was dispatched to check on the occupants of the house and was available on scene. The dispatcher asked him why he needed a second ambulance, but never got a response. FF1 noticed that cross-lay #1 was flat so he shut the line down, disconnected the section of hose closest to the carport not exposed to flames, and retrieved a nozzle from the arriving AT2 with fire fighter #3 (FF3). Note: This was the same line that the victim had taken into the house. During the fire investigation it was discovered that the hoseline was burnt through at the carport threshold. FF1 then assisted FF2 in flaking out cross-lay #2 to the house. FF1 saw that AE1 had arrived with fire fighter #4 (FF4). He told FF4 about the victim missing in the structure and the inability to get him out. After cross-lay #1 was disconnected from the burnt section of hose and a new nozzle connected, it was placed back in service. FF1 took cross-lay #1 and sprayed water on the front porch until AE2 ran out of water. When AE2 ran out of water, FF1 dropped cross-lay #1 in the front yard and drove AE1 a ½ mile down the road to a hydrant to fill up. Arriving apparatus from Charlie Fire Department then supplied AE2.

Activities of AT2 and AE1

AT2 and AE1 marked on scene at 1328 hours with fire blowing out the windows on the A-side, front door and carport entry. FF4 set AE1 to pump and supplied their 1,000 gallons of water to AE2 via a 2½-in supply line. AT2 did not supply or receive any water to or from apparatus on scene. No hoselines were stretched from AT2 or AE1. FF4 monitored the pump panels of AE1 and AE2 while FF3 briefly assisted FF2 with charging cross-lay #2. FF3 then picked up cross-lay #1 and took it with him as he entered the structure briefly via the front door. He briefly sprayed water as he yelled for the victim; he heard neither a response nor a sounding PASS device. He was quickly pushed back through the front door by intense heat and fire. FF3 made a second entry through the front door to locate the victim with no success.

Activities of CE1 and CE3

CE3 marked on scene at 1338 hours with their fire chief (CFC) and fire fighter #5 (FF5); the CFC stated the house was “heavily involved” with fire. The fire had not vented through the roof, but was visible from A-side and B-side window and door openings. AE1 advised the CFC that he was going to get water. FF5 took a 2½-in supply line from CE3 and supplied AE2 with its’ 3,000 gallons of water. FF5 operated the pump panel on CE3 with assistance from the CFC. The CFC pulled one preconnected 150-ft 1¾-in hoseline to the front yard and one 100-ft 1¾-in hoseline to the A-D corner. CE1 marked on scene at 1339 hours with fire fighter #6 (FF6). FF6 exited his apparatus and briefly spoke to FF4 about what was going on. FF6 then picked up what is believed to have been cross-lay #2 that was placed on the ground and not in use. He stated the line had too much pressure on it for him to handle and that he did not see anyone operating the pump panel on AE2 to fix it. Note: When interviewed, one pump operator stated the department did not have a set pump discharge pressure for different or multiple lines run from an apparatus. A pump operator would adjust the pressure according to fire fighters operating the hand line. He also noticed a 1-in booster line from AR1 in use by Alpha Fire Department members on the A-side. The CFC took the 2½-in supply line from CE1 and hooked it into CE3. The CFC then operated a hoseline at the A-D corner while FF6 operated a hand line at the A-B corner (not clear which apparatus the line was pulled from). A third fire fighter from Charlie Fire Department arrived on scene in his (POV) and assisted a fire fighter with flowing water into the A-side bay window. The fire fighters on CE1 and CE3 were unable to make an interior attack or get close to the burning house because they had responded to the incident without their structural fire fighting gear. Note: All Charlie Fire Department members on scene of this incident responded without structural firefighting gear. Their gear had been taken to their residences in case they responded to incidents from home, instead of responding to the fire station to pick up an apparatus. This was a common practice by the Fire Chief and his members. When CE1 and CE3 tank water ran out, FF6 and CFC left in CE1 and CE3 to find the hydrant ½ mile down the road. When they returned, the victim was being removed from the structure. By this time, AE1 had returned and was positioned at the B-C corner and AE1 was again, out of water.

Victim Discovery

Individual responders interviewed by NIOSH remarked on several air packs taken off by fire fighters and left unattended on the fireground. These air packs were left on and the activated integrated PASS devices continued to alarm. This may have hindered the efforts of fire fighters to locate the victim during rescue efforts because they could not determine whether the PASS alarm was coming from inside or outside the structure. A town police officer who had been on scene since the initial dispatch was assisting fire fighters in trying to locate the victim from the exterior. FF4 came upon a burnt glove on the ground in front of the C-side kitchen window. The police officer grabbed an extension ladder and placed it against the window sill of the kitchen window. The police officer stated the fire had burned itself out in this area and the smoke was light enough to get a good view inside the house. He noticed the victim’s hand resting on the kitchen counter under some debris. He immediately alerted fire fighters who were close by. Two fire fighters entered through the carport door, into the laundry room and turned left into the kitchen where they saw the police officer in the window. The victim was found on the kitchen floor in front of the kitchen sink; he was removed from the house and pronounced dead on the scene by County EMS responders at 1420 hours. A nozzle connected to the original cross-lay #1, the victim’s radio, helmet, face piece, SCBA, and a boot were found scattered around him (see Photo 5). It appeared that the helmet, face piece, and SCBA were burned off of the victim. The nozzle was found with the bale fully opened at a 30 degree fog setting.

|

| 1. Victim – 112″ from carport door 2. SCBA – 85″ from carport door 3. Face Piece – 128″ from carport door 4. Helmet – 139½” from carport door 5. Radio – 147″ from carport door 6. Boot – 94″ from carport door 7. Nozzle – 101″ from carport door Photo 5. Number cues placed to document |

Fire Behavior and Spread

During their investigation, the fire marshal and sheriff’s office investigators believed that the chimney flue failed allowing radiant heat and flame to travel through the open sides of the cinder blocks and impinge on combustible materials in the attic. It is believed that the fire smoldered for a while in the attic before finding a reliable fuel source. Fire burned across the C-side of the structure’s attic before burning down into the living area where the wood stove was located (see Photo 6). Thick black smoke was filling the structure when the victim and FF2 entered through the carport for the first time. No flames were immediately visible according to FF2. FF1 was met with the same smoke conditions when he opened the front door and the bay window broke under extreme heat conditions. Flames throughout the house erupted moments later. FF1 and FF2 do not recall any type of explosion or “puffs” of smoke before the house erupted in flames. The sheriff’s office investigator believed that the house “flashed,” trapping the victim and exposing him to extreme heat and fire conditions after the door and window were opened, which would have allowed fresh air (oxygen) to join the fuel mixture (heavy dark smoke) inside, ultimately leading to the flashover.

|

|

Photo 6. Fire damage to living room area |

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatality:

- Fire fighters operating on a fireground and entering a burning structure without adequate training.

- Insufficient manpower to combat the fire.

- No incident command system established.

CAUSE OF DEATH

According to the county medical examiner’s office, the victim died from smoke inhalation and thermal burns. The victim’s carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) was 35%.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters receive essential training consistent with national consensus standards on structural fire fighting before being allowed to operate at a fire incident.

Discussion: Training on structural fire fighting is essential for fire fighter safety and survival. This training should include, but not be limited to, departmental standard operating procedures, fire fighter safety, building construction, fire behavior, and fireground tactics. NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications was established to facilitate the development of nationally applicable performance standards for fire service personnel.3 NFPA 1500 Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, Chapter 5, requires that the fire department provide an annual skills check to verify minimum professional qualifications of its members.4 The purpose of NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications is to show clear and concise requirements that can be used to determine that an individual, when measured to the standard, possesses the knowledge, skills, and abilities to perform as a fire fighter and that these requirements can be used by any fire department in the country. Once the basic skills and knowledge sets of Fire Fighter I are met the individual can continue on to Fire Fighter II. Staying proficient at these levels is only possible through a training regime developed by the fire department or training entity that covers topics like ventilation, hazard recognition, fire behavior, incident command system, scene size-up, and basic water operations.

The state of Alabama does offer a non-mandatory 160 hour volunteer fire fighter certification course. This course is optional and not required to be a volunteer fire fighter in the state of Alabama. Neither the victim nor fire fighters from his department on scene had completed this training. During interviews, the fire chief advised NIOSH investigators that the victim and two other fire fighters were scheduled to start this training in January 2009. The chief currently has nine fire fighters in the 160 hour certification program that are scheduled to graduate in June 2009. This basic training provides fire fighters with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to make sound, safe decisions before engaging in active fire suppression. Fire departments should pair untrained and inexperienced fire fighters with a trained and experienced fire fighter.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should develop, implement, and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for fireground operations.

Discussion: Written SOPs enable individual fire department members an opportunity to read and maintain a level of assumed understanding of operational procedures. Conversely, fire departments can suffer when there is an absence of well developed SOPs. The NIOSH Alert, Preventing Injuries and Deaths of Fire Fighters identifies the need to establish and follow fire fighting policies and procedures.5 Guidelines and procedures should be developed, fully implemented and enforced to be effective. The following NFPA Standards also identify the need for written documentation to guide fire fighting operations:

NFPA 1500 Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program states that fire departments shall prepare and maintain policies and standard operating procedures that document the organizational structure, membership, roles and responsibilities, expected functions, and training requirements, including the followin….(4) The procedures that will be employed to initiate and manage operations at the scene of an emergency incident.4

NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System states that standard operating procedures (SOPs) shall include the requirements for implementation of the incident management system and shall describe the options that are available for application according to the needs of each particular situation.6

NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments states that the authority having jurisdiction shall promulgate the fire department’s organizational, operational, and deployment procedures by issuing written administrative regulations, standard operating procedures, and departmental orders.7

The victim’s fire department had not implemented any verbal or written SOPs for their members. An effective SOP can aid in the decision making process when on the fireground.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained to follow the two-in/two-out rule and maintain crew integrity at all times.

Discussion: NFPA 1500 Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program states that the two-in/two-out rule should be used when making entry into a hazardous area.4 The team members should be in communication with each other through visual, audible, or electronic means to coordinate all activities, and determine if emergency rescue is needed. Working alone in a structure fire does not provide a fire fighter a back-up plan if he or she gets in trouble.

Crew integrity relies on knowing your team members and the team leader, maintaining visual contact (if visibility is low, teams must stay within touch or voice distance of one another), communicating needs and observations to the team leader, rotating to rehab, staging as a team, and watching fellow team members by means of a buddy system. Crew integrity is being able to maintain a cohesive crew over a period of time. Fire fighter accountability is an important aspect of fire ground safety that can be compromised when teams are split up. Being able to operate as a crew and understanding one’s limitations will benefit the crew’s safety and overall incident outcome. This is especially important during interior fire attack. Names on coats, reflective shields or company numbers on helmets, and helmet and turnout clothing colors are visual ques that fire fighters can use to maintain crew integrity in poor visibility.

During this incident, the victim entered the house alone and was unable to self-rescue or be rescued by on scene fire fighters.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that adequate numbers of apparatus and fire fighters are on scene before initiating an offensive fire attack in a structure fire.

Discussion: Fire suppression operations should be organized to ensure that the fire department’s fire suppression capability includes sufficient personnel, equipment, and other resources to deploy fire suppression resources efficiently, effectively, and safely.7 Volunteer fire departments need to identify minimum staffing requirements to ensure that an adequate number of members are available to operate safely and effectively. Rural areas have a lower population density and require at least six people (two-in/two-out plus the incident commander and pump operator) on scene before fire suppression operations can take place. 7 If staffing is known to be limited during the day, then automatic mutual aid agreements should be implemented with surrounding departments to ensure a timely response of resources. Fire departments should develop and establish good working relationships with surrounding departments so that reciprocal assistance and mutual aid is readily available when emergency situations escalate beyond response capabilities. NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments states that fire departments should have the capability for sustained operations to include:

- fire suppression

- engagement in search and rescue

- forcible entry

- ventilation

- preservation of property

- accountability for personnel

- dedicated rapid intervention team (RIT)

- provision for support activities for situations that are beyond the capability of the initial attack

During this incident, the initial responding units consisted of a rescue truck with one fire fighter and an engine with the victim and a fire fighter. The next due mutual aid station did not have any available personnel to respond to the incident scene. This level of initial response did not meet what is outlined in NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments and is insufficient for fire fighting operations. The fire department had not outlined minimum staffing procedures for departmental responses. In rural areas and areas with long response times, automatic mutual aid should be established to ensure enough fire fighters arrive in a timely manner to safely perform fireground tasks. Having only three fire fighters to sustain operations on the fireground negatively affected the control of the fire and overwhelmed the fire fighters that were on scene.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should ensure that officers and fire fighters know how to evaluate risk versus gain and perform a thorough scene size-up before initiating interior strategies and tactics.

Discussion: Situational awareness is a highly critical aspect of human decision making: the understanding of what is happening around you, projecting future situation events, comprehending information and its relevance, and an individual’s perception.8 This is especially important when conducting an initial size-up. The initial size-up of the incident helps to determine the number of fire fighters and the amount of apparatus and equipment needed to control the fire, assists in determining the most effective point of fire attack, venting heat and smoke, and whether the attack should be offensive or defensive. The size-up should include an evaluation of factors such as the fire size and location, length of time the fire has been burning, conditions on arrival, occupancy, fuel load and presence of combustible or hazardous materials, exposures, time of day, and weather conditions.7 Information on the structure itself including size, construction type, age, condition, evidence of renovations, lightweight construction, and loads on roof and walls will aid in determining strategies and tactics. Fire fighters need to consider warning signs like dense black smoke, turbulent smoke, smoke puffing around doorframes, discolored glass, and a reverse flow of smoke back inside the building before making entry into a structure fire.9 The level of risk to the fire fighters must be balanced against the potential to save lives or property.6

During this incident, it was reported that all occupants from the residence were accounted for. There was no life threatening emergency on scene that would have required fire fighters to rush into the house before thinking about their risks and potential gains from combating a fire with limited staffing. Incident command was not established, fire fighters on scene had limited fire fighting training, manpower was insufficient for the incident, and all occupants of the house were accounted for prior to their arrival. A decision to combat this fire defensively until additional resources arrived was warranted. A flashover occurred trapping the victim within the structure and overwhelming the fire fighters and available resources on scene.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should develop, implement, and enforce a written incident management system to be followed at all emergency incident operations and ensure that officers and fire fighters are trained on how to implement the incident management system.

Discussion: NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program4 and NFPA 1561 Standard on Emergency Services Incident Management System6 both state that an incident management system (IMS) should be utilized at all emergency incidents (including but not limited to training exercises). NFPA 1561, Chapter 3.3.29 defines the incident management system (also known as the incident command system (ICS)) as “a system that defines the roles and responsibilities to be assumed by responders and the standard operating procedures to be used in the management and direction of emergency incidents and other functions.6 Chapter 4.1 states “the incident management system shall provide structure and coordination to the management of emergency incident operations to provide for the safety and health of emergency services organization (ESO) responders and other persons involved in those activities.” Chapter 4.2 states “The incident management system shall integrate risk management into the regular functions of incident command.” Each fire department or emergency services organization (ESO) should adopt an incident management system to manage all emergency incidents. The IMS should be defined and in writing and include standard operating procedure (SOPs) covering the implementation of the IMS. The IMS should include written plans that address the requirements of different types of incidents that can be anticipated in each fire department’s or ESO’s jurisdiction. The IMS should address both routine and unusual incidents of differing types, sizes and complexities. The IMS covers more than just fireground operations. The IMS must cover incident command, accountability, risk management, communications, rapid intervention crews (RIC), roles and responsibilities of the incident safety officer (ISO), and interoperability with multiple agencies (police, emergency medical services, state and federal government, etc.) and surrounding jurisdictions (mutual aid responders).

NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments states, “the incident commander shall be responsible for the overall coordination and direction of all activities for the duration of the incident.”7 Furthermore, the incident command system/incident management system is a standardized on-scene incident management concept designed specifically to allow responders to adopt an integrated organizational structure equal to the complexity and demands of any single incident or multiple incidents without being hindered by jurisdictional boundaries.10 The IC has several responsibilities upon his arrival including safety and health of responders on scene, stabilizing the incident, developing strategies, and overall management of the incident. Without an IC, the safety of the fire fighter and fireground operations can be compromised.

During this incident, no IC was established. The victim, FF1, and FF2 performed tasks that included a walk around of the house, stretching an attack line to an entry point, and setting up a water supply. Not having an IC to provide direction on managing the incident through sound strategies and tactics contributed to the fire getting out of control and fatally injuring the victim.

Recommendation #7: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained in essential self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and emergency survival skills.

Discussion: Fire fighters must act promptly when they become lost, disoriented, injured, low on air, or trapped.11-16 First, they must transmit a distress signal while they still have the capability and sufficient air, noting their location if possible. The next step is to manually activate their PASS device. To conserve air while waiting to be rescued, fire fighters should try to stay calm, be focused on their situation and avoid unnecessary physical activity. They should survey their surroundings to get their bearings and determine potential escape routes such as windows, doors, hallways, changes in flooring surfaces, etc.; and stay in radio contact with the IC and other rescuers. Additionally, fire fighters can attract attention by maximizing the sound of their PASS device (e.g. by pointing it in an open direction), pointing their flashlight toward the ceiling or moving it around, and using a tool to make tapping noises on the floor or wall. A crew member who initiates a Mayday call for another person should quickly try to communicate with the missing member via radio and, if unsuccessful, initiate another Mayday providing relevant information on the missing fire fighter’s last known location.

During this incident, it was never determined whether the victim’s PASS device was heard. The victim radioed for assistance but did not declare a Mayday. The victim was found within arms reach of his hoseline that led outside (approximately eight feet to the door).

Recommendation #8: Fire departments should ensure that protocols are developed to assist fire fighters in issuing a Mayday so that fire fighters and dispatch centers know how to respond.

Discussion: A radio transmission reporting a trapped or downed fire fighter is the highest priority transmission that an IC can receive. Mayday transmissions must always be acknowledged and immediate action must be taken.11, 12 As soon as fire fighters become lost or disoriented, trapped or unsuccessful at finding their way out of the interior of a structural fire, they must initiate emergency radio transmissions. A Mayday call should receive the highest communications priority from dispatch, the IC, and all other units on-scene. Dispatchers should be trained to monitor radio traffic so that they can assist the IC in acknowledging distress calls. Dispatchers are not exposed to fireground noise like the IC, which may distract the IC from acknowledging radio transmissions.

During this incident, the victim made at least two calls for help inside the house. The department did not have procedures for ensuring that all on-scene fire fighters and the dispatch center were aware of the trapped fire fighter, that information crucial for locating the fire fighter was collected, and that organized rescue attempts were initiated. Individual attempts to find and rescue the victim were unsuccessful and 58 minutes passed from the victim’s initial call for help and dispatch being notified of the victim being in trouble.

Recommendation #9: Fire departments should ensure that a properly trained incident safety officer (ISO) is established at structure fires.

Discussion: NFPA 1521 Standard for Fire Department Safety Officer defines the role of the ISO at an incident scene and identifies duties such as reporting pertinent fireground information to the IC; ensuring the department’s accountability system is in place and operational; monitoring radio transmissions and identifying barriers to effective communications; and ensuring that established safety zones, collapse zones and other designated hazard areas are communicated to all members on scene.17 Although the presence of a safety officer does not diminish the responsibility of individual fire fighters and fire officers for safety, the ISO adds a higher level of attention and expertise to help the individuals. The ISO must have particular expertise in analyzing safety hazards and must know the particular uses and limitations of protective equipment.6

Having an ISO standard operating procedure and an available and trained individual as an ISO on this incident may have prevented the victim from going into the structure alone; and could have provided assistance in handling the victim’s call for help.

Recommendation #10: Fire departments should ensure that a rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available at structure fires.

Discussion: A RIT should be designated and available to respond before interior attack operations begin. The team should report to the incident commander and be available within the incident’s staging area. The RIT should have all tools necessary to complete the job, e.g., search and rescue ropes, Halligan bar and flat-head axe combo, first-aid kit, and resuscitation equipment.9 These teams can intervene quickly to rescue a fire fighter who is running out of breathing air, becomes disoriented, lost in smoke filled environments, trapped by fire, or involved in structural collapse.4

During this incident, there were only two other fire fighters on scene when the victim radioed for help. Neither one of them had received training on rapid intervention or basic fire fighting. NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, Chapter 8.8, Rapid Intervention for Rescue of Members, provides detailed guidelines for the deployment of rescue teams at emergency incidents.4 Chapter 8.8.1 states “The fire department shall provide personnel for the rescue of members operating at emergency incidents.” The staffing requirements set forth by NFPA 1720 Standard for the Organization and Development of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Volunteer Fire Departments were not met; hence, not allowing them to establish a RIT or follow a two-in/two-out rule. Note: Although volunteer fire departments in the State of Alabama are not governed by federal regulations set forth by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, it is good practice that OSHA’s two-in/two-out rule, 29 CFR 1910.134 (g)(4)(i) be adopted and written into fire department standard operating procedures.

Recommendation #11: Fire departments should ensure that properly coordinated ventilation is conducted on structure fires.

Discussion: Ventilation is the systematic removal of heated air, smoke, and fire gases from a burning building and replacing them with cooler air.9 Properly coordinated ventilation can decrease how fast the fire spreads, increase visibility, and lower the potential for flashover or backdraft. Proper ventilation reduces the threat of flashover by removing heat before combustibles in a room or enclosed area reach their ignition temperatures, and can reduce the risk of a backdraft by reducing the potential for superheated fire gases and smoke to accumulate in an enclosed area. Properly ventilating a structure fire will reduce the tendency for rising heat, smoke, and fire gases, trapped by the roof or ceiling, to accumulate, bank down, and spread laterally to other areas within the structure.

The ventilation opening may produce a chimney effect causing air movement from within a structure toward the opening. This air movement helps facilitate the venting of smoke, hot gases and products of combustion, but may also cause the fire to grow in intensity and may endanger fire fighters who are between the fire and the ventilation opening. For this reason, ventilation should be closely coordinated with hoseline placement and offensive fire suppression tactics. Close coordination means the hoseline is in place and ready to operate so that when ventilation occurs, the hoseline can overcome the increase in combustion likely to occur. If a ventilation opening is made directly above a fire, fire spread may be reduced, allowing fire fighters the opportunity to extinguish the fire. If the opening is made elsewhere, the chimney effect may actually contribute to the spread of the fire.9 The IC needs to consider the following and how it will affect ventilation and overall control of the fire:

- Who will ventilate (knowledge and skills)

- What type of ventilation

- When to ventilate

- Where to ventilate

- Why ventilate

- How to properly and safely ventilate

The two types of ventilation are vertical and horizontal. During vertical ventilation the natural convection of the heated gases creates upward currents that draw the fire and heat in the direction of the vertical opening. Horizontal ventilation allows for heat, smoke, and gases to escape by means of a doorway or window, but is highly influenced by the location and extent of the fire and should be cautioned if the fire is in the attic.9

During this incident, no attempt was made to ventilate the attic fire in the house. The original roof layers had been covered with a tin roof which would have hindered fire fighter’s attempts to ventilate the roof. No windows were broken out on the first floor.

Recommendation #12: Fire departments should ensure that driver/pump operators receive adequate training to operate and maintain a water supply to hoselines on the fireground.

Discussion: NFPA 1002 Standard for Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications sets minimum qualifications for driver/operators. The pump operator is responsible for the life safety of all personnel exposed to dangerous situations that are operating hoselines being supplied by the pumper.18 The qualities and skill sets needed by a pump operator include an understanding of different types of pumping apparatus, proper apparatus placement to maximize water supply efficiency, fire pump theory and operation, hydraulic calculations, and water supply choices. In addition, NFPA 1002 Standard for Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications requires any driver/operator who will be responsible for operating a fire pump to also meet requirements of NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications for Fire Fighter I.3, 19

During this incident, fire fighters from the victim’s department operated the tanker tasked with supplying water to fireground hoselines. The pump operator had received peer led hands-on training provided to him by members of this department. Fire fighters on scene recall having too much pressure on hoselines, not enough pressure, or seeing the pump panel unattended. The hoseline originally taken into the house by the victim was shut down when observed that it was flat. The closest section not exposed to fire was disconnected and another nozzle placed on it for use.

Recommendation #13: Fire departments should ensure that all fire fighters engaged in fireground activities wear the full array of personal protective equipment (PPE) issued to them.

Discussion: NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program contains the general recommendations for fire fighter protective clothing and protective equipment.3 Chapter 7.1.1 specifies that “the fire department shall provide each member with protective clothing and protective equipment that is designed to provide protection from the hazards to which the member is likely to be exposed and is suitable for the tasks that the member is expected to perform.” Chapter 7.1.2 states “protective clothing and protective equipment shall be used whenever the member is exposed or potentially exposed to the hazards for which it is provided.” Chapter 7.2.1 states “members who engage in or are exposed to the hazards of structural fire fighting shall be provided with and shall use a protective ensemble that shall meet the applicable requirements of NFPA 1971 Standard on Protective Ensembles for Structural Fire Fighting and Proximity Fire Fighting.”20

On the day of incident, Charlie Fire Department members responded from work to the fire house to pick up CE1 and CE3. They responded to the incident scene without their department issued protective ensembles. Upon arrival to the incident, Alpha Fire Department members were trying to control the fire and make an attempt to enter the house for the victim. Their firefighting and rescue abilities were limited by the mutual aid department not having their gear with them.

Recommendation #14: Fire departments should ensure that fire fighters are trained to react to PASS and SCBA low air alarms, and that procedures are developed to properly shut down and secure a SCBA and its PASS device.

Discussion: During interviews, witnesses and fire fighters reported to NIOSH investigators that audible alarms were sounding from SCBAs doffed and placed on the fireground. NIOSH investigators are not sure if a PASS alarm on the victim could have been heard or distinguished from the alarms sounding outside. It was not determined if these alarms were from the lack of movement or a low air alarm. With alarms sounding and no one reacting to them, it is possible that search and rescue operations could be hindered or important radio messages not heard or understood, especially a brief Mayday radio call. During this incident, the victim did transmit a radio transmission requesting help early in the event that was heard by one fire fighter.

A fire fighter not reacting to the alarms is a symptom of desensitization (ignoring the sounds) and may cause a fire fighter to continue on with their assignment(s). If fire fighters are trained to react to alarms by investigating, then fire fighters can focus on the source of the alarm and take a positive action to correct it (i.e. responding to a downed fire fighter, properly securing the SCBA, or resetting the PASS device). Fire departments should develop standard operating procedures or guidelines that address proper doffing of a SCBA that is not in use, to include: turning the cylinder off, bleeding the line, and resetting or securing the PASS device.

Additionally,

Recommendation #15: States, municipalities, and authorities having jurisdiction should consider requiring mandatory training for fire fighters.

Discussion: Fire fighters have a high rate of injury death compared to other occupations.21 Fire fighters need to take advantage of available training and certification programs within their jurisdiction so that safe and sound decisions can be made on the fireground. The state of Alabama has set mandatory minimal training requirements for an individual wishing to become a career fire fighter, but no mandatory or minimal training requirements have been set for individuals wanting to volunteer as a fire fighter.2 Individuals may volunteer with a fire department and participate in fire ground activities in Alabama without being certified as a fire fighter. The state fire academy does offer a non-mandatory 160 hour certification course to individuals who are active volunteer members with a fire department and wish to become a certified volunteer fire fighter.2 This course is equivalent to Fire Fighter I as outlined in NFPA 1001 Standard for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications and can be completed over a 24 month period, but the victim and fellow fire department members had not taken the training. Since 2002, NIOSH has investigated three separate incidents that resulted in four fatalities of volunteer fire fighters in the state of Alabama.22-24 NIOSH investigators cited the lack of training as a contributing factor in all of them.

REFERENCES

- Alabama Fire College. So you want to be a volunteer fire fighter. [http://www.alabamafirecollege.org/wanttobeavolff.htm]. Date accessed: April 2009. (Link no longer available 9/19/2011)

- Alabama Fire College. Requirements for certified fire fighter. [http://www.alabamafirecollege.org/Commission/2007/360-X-2-2007.pdf]. Date accessed: April 2009. (Link no longer available 9/19/2011)

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1001 Standard for fire fighter professional qualifications. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500 Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NIOSH [1994]. NIOSH Alert: preventing injuries and deaths of fire fighters. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 94-125. [https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire.html].

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1561 Standard on emergency services incident management system. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2004]. NFPA 1720 Standard for the organization and deployment of fire suppression operations, emergency medical operations, and special operations to the public by volunteer fire departments. 2004 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Endsley MR, Garland J [2000]. Situational awareness analysis and measurement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- IFSTA [2008]. Essentials of fire fighting. 5th ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Incident Command System eTool.external icon [https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/ics/index.html]. Date accessed: January 2009.

- Carter W, Childress D, Coleman R, et al. [2000]. Firefighter’s Handbook: essentials of firefighting and emergency response. Albany, NY: Delmar Thompson Learning.

- FDSOA (Fire Department Safety Officers Association) [2002]. MAYDAY-MAYDAY-MAYDAY. By JJ Hoffman. Health and Safety for Fire and Emergency Service Personnel 13(4):8.

- Angulo RA, Clark BA, Auch S [2004]. You called mayday! Now what? Fire Engineering, 157(9):93-95

- DiBernardo JP [2003]. A missing firefighter: give the mayday. Firehouse Nov:68-70.

- Sendelbach TE [2004]. Managing the fireground mayday: the critical link to firefighter survival. [http://www.firehouse.com/node/73134]. Date accessed: February 2009. (Link updated 9/19/2011 – No longer available 10/4/2012)

- Miles J, Tobin J [2004]. Training notebook: mayday and urgent messages. Fire Engineering, 157(4):22.

- NFPA [2008]. NFPA 1521 Standard for fire department safety officer. 2008 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- IFSTA [1999]. Pumping apparatus driver/operator handbook. 1st ed. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, International Fire Service Training Association.

- NFPA [2009]. NFPA 1002 Standard for fire apparatus driver/operator professional qualifications. 2009 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1971 Standard on protective ensembles for structural fire fighting and proximity fire fighting. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Clarke C, Zak MJ [1999]. Fatalities to law enforcement officers and firefighters, 1992-1997. Compensation and Working Conditions.

- NIOSH [2006]. Junior Volunteer Fire Fighter Dies and Three Volunteer Fire Fighters are Injured in a Tanker Crash – Alabama. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. F2006-25. [https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200625.html].

- NIOSH [2006]. Two Volunteer Fire Fighters Die When Struck by Exterior Wall Collapse at a Commercial Building Fire Overhaul – Alabama. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. F2006-07. [https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200607.html].

- NIOSH [2002].Volunteer Fire Fighter Dies and Two are Injured in Engine Rollover – Alabama. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. F2002-16. [https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200216.html].

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by Stacy C. Wertman and Stephen T. Miles, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Fatality Investigations Team, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH located in Morgantown, WV. An expert technical review was provided by Harry R. Carter, Ph.D. The analysis of the victim’s turnout gear was conducted by Jeff Stull, International Personnel Protection, Inc. Vance Kochenderfer, NIOSH Quality Assurance Specialist, National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory, conducted an evaluation of the victim’s self-contained breathing apparatus.

|

|

Diagram. Incident scene when victim called for help. |

APPENDIX

Status Investigation Report of Two

Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus from an Alabama Fire

Department

Submitted By an

Alabama Sheriff’s Office

NIOSH Task Number 16601

Background

As part of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter

Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, the Technology Evaluation Branch agreed to examine and evaluate two SCBA identified as Mine Safety Appliances Company FireHawk M7, 4500 psi, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). This SCBA status investigation was assigned NIOSH Task Number 16601. The Sheriff’s Office was advised that NIOSH would provide a written report of the inspections and any applicable test results of these SCBA from the Fire Department.

The SCBAs, contained within two boxes, were delivered to the NIOSH facility in Bruceton,

Pennsylvania on April 4, 2009. After its arrival, the packages were taken to building 108 and stored under lock until the time of the evaluation.

SCBA Inspection

The packages were opened in the Firefighter SCBA Evaluation Lab (building 02) and a complete visual inspection was conducted by Eric Welsh, Engineering Technician, NPPTL. The first SCBA examined, sent as a comparison unit, designated Unit #2, was opened and inspected on December 7, 2009. The second SCBA examined was inspected on December 7, 2009 and designated as Unit #1. Unit #1 SCBA was the unit worn by the firefighter. The SCBA’s were examined, component by component, in the condition as received to determine their conformance to the NIOSH approved configuration. The visual inspection process was videotaped. The unit #1 SCBA was identified as the MSA FireHawk M7, 30 minute, 4500 psi units, NIOSH approval numbers TC-13F-548CBRN or TC-13F-565CBRN. The unit #2 SCBA, the comparison unit, was identified as the MSA FireHawk M7, 4500 psi unit, but was supplied without a cylinder or facepiece, therefore could have been assembled as NIOSH approval numbers were listed as TC-13F-548CBRN, TC-13F-549CBRN or TC-13F-550CBRN.

The complete SCBA inspection is summarized in Appendix I of the full report. The condition of each major component was also photographed with a digital camera. Images of the SCBA are contained in Appendix III of the full report.

Unit #1, due to extensive damage, could not be safely pressurized and tested.

Unit # 2 was not tested as it was supplied for comparison purposes only.

SCBA Testing

The purpose of the testing is to determine the SCBA’s conformance to the approval performance requirements of Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 84 (42 CFR 84). Further testing is also conducted to provide an indication of the SCBA’s conformance to the National Fire

Protection Association (NFPA) Air Flow Performance requirements of NFPA 1981, Standard on

Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus for the Fire Service, 1997 Edition.

NIOSH SCBA Certification Tests (in accordance with the performance requirements of

42 CFR 84):

1. Positive Pressure Test [§ 84.70(a)(2)(ii)]

2. Rated Service Time Test (duration) [§ 84.95]

3. Static Pressure Test [§ 84.91(d)]

4. Gas Flow Test [§ 84.93]

5. Exhalation Resistance Test [§ 84.91(c)]

6. Remaining Service Life Indicator Test (low-air alarm) [§ 84.83(f)]

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Tests (in accordance with NFPA 1981,

1997 Edition):

7. Air Flow Performance Test [Chapter 5, 5-1.1]

No report on testing is included as no testing was conducted.

Summary and Conclusions

Two SCBA’s from the Fire Department were submitted to NIOSH by the Sheriff’s office for evaluation. The SCBAs were delivered to NIOSH on April 24, 2009 and inspected on December 7, 2009. The units were identified as MSA Company FireHawk Mark 7, 4500 psi, SCBA (NIOSH approval number TC-13F-548CBRN or TC-13F-565CBRN for unit 1, a 30 minute duration unit). Unit #1 suffered extensive damage from heat and fire and was covered with dirt, grime, foreign particulate material and soot. Numerous pieces of the SCBA were missing. The cylinder valve as received was heavily damaged, the plastic hand wheel was melted and the valve was inoperable. The gauges were all unreadable and heavily damaged. The regulator and facepiece were heavily damaged, unusable and the regulator plastic materials had been melted and were bonded onto the facepiece. The SCBA air cylinder was heavily damaged. The outside cylinder covering was missing and the cylinder wrapping filament material was exposed.

Unit # 2 was submitted as a comparison SCBA. The unit was not supplied with a cylinder or a facepiece. The NFPA approval label mounted on unit # 2 read SEI 1981-2007. The NFPA approval label mounted on the PASS unit read SEI 1982-2007 PASS. The NIOSH label listed approvals TC-13F-548CBRN, TC-13F-549CBRN and TC-13F-550CBRN. The unit had been taken out of service due to the PASS unit not operating. There were no batteries included with the PASS unit and the red activation button was missing. The regulators, gauges and other components supplied appeared to be in good condition.

The air cylinder on Unit #1 was so heavily damaged that the re-test date label was not readable and a re-test date could not be determined. There were no air cylinders supplied with Unit #2.

In light of the information obtained during this investigation, NIOSH has proposed no further action on its part at this time. Following the visual inspection, the SCBA were returned to storage pending return to the Sheriff’s office.

If the Unit #2 is to be placed back in service, this unit must have the PASS unit repaired. In addition, the overall SCBA should be tested and inspected by a qualified service technician before placing it back in service including such testing and other maintenance activities as prescribed by the schedule from the SCBA manufacturer.

Addendum

This addendum concerns the information retrieved from that data logger. The Unit #1 SCBA was equipped with a data logging device.

On August 17, 2010, after some discussion, NIOSH was able to enlist the assistance of the Mine Safety Appliances Company (MSA) in down loading any data that could be retrieved off of the data logger unit. Due to the extensive damage of the SCBA, MSA had to take extraordinary measures to try and retrieve the information as the designed data retrieval method was not functional.

On January 11, 2011, MSA reported to NIOSH on the results of the data retrieval attempt. According to MSA, the data logger was too damaged to retrieve any significant data. Their report was as follows:

“This data logging unit received heat sufficient to melt solder on the printed circuit board. MSA removed the storage chip from the damaged board and placed it onto a functional board. MSA was able to recover a log but there was no meaningful data in the file. The chip was likely damaged.”

From the information obtained during this additional part of the investigation, NIOSH proposes no further action on its part at this time.

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In fiscal year 1998, the Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative. NIOSH initiated the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program to examine deaths of fire fighters in the line of duty so that fire departments, fire fighters, fire service organizations, safety experts and researchers could learn from these incidents. The primary goal of these investigations is for NIOSH to make recommendations to prevent similar occurrences. These NIOSH investigations are intended to reduce or prevent future fire fighter deaths and are completely separate from the rulemaking, enforcement and inspection activities of any other federal or state agency. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the deaths in order to provide a context for the agency’s recommendations. The NIOSH summary of these conditions and circumstances in its reports is not intended as a legal statement of facts. This summary, as well as the conclusions and recommendations made by NIOSH, should not be used for the purpose of litigation or the adjudication of any claim. For further information, visit the program website at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

|

This page was last updated on 06/11/09.