Nine Career Fire Fighters Die in Rapid Fire Progression at Commercial Furniture Showroom - South Carolina

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2007-18 Date Released: February 11, 2009

SUMMARY

On June 18, 2007, nine career fire fighters (all males, ages 27 – 56) died when they became disoriented and ran out of air in rapidly deteriorating conditions inside a burning commercial furniture showroom and warehouse facility. The first arriving engine company found a rapidly growing fire at the enclosed loading dock connecting the showroom to the warehouse. The Assistant Chief entered the main showroom entrance at the front of the structure but did not find any signs of fire or smoke in the main showroom.

|

|

Incident Scene |

He observed fire inside the structure when a door connecting the rear of the right showroom addition to the loading dock was opened. Within minutes, the fire rapidly spread into and above the main showroom, the right showroom addition, and the warehouse. The burning furniture quickly generated a huge amount of toxic and highly flammable gases along with soot and products of incomplete combustion that added to the fuel load. The fire overwhelmed the interior attack and the interior crews became disoriented when thick black smoke filled the showrooms from ceiling to floor. The interior fire fighters realized they were in trouble and began to radio for assistance as the heat intensified. One fire fighter activated the emergency button on his radio. The front showroom windows were knocked out and fire fighters, including a crew from a mutual-aid department, were sent inside to search for the missing fire fighters. Soon after, the flammable mixture of combustion by-products ignited, and fire raced through the main showroom. Interior fire fighters were caught in the rapid fire progression and nine fire fighters from the first-responding fire department died. At least nine other fire fighters, including two mutual-aid fire fighters, barely escaped serious injury.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- develop, implement and enforce written standard operating procedures (SOPs) for an occupational safety and health program in accordance with NFPA 1500

- develop, implement, and enforce a written Incident Management System to be followed at all emergency incident operations

- develop, implement, and enforce written SOPs that identify incident management training standards and requirements for members expected to serve in command roles

- ensure that the Incident Commander is clearly identified as the only individual with overall authority and responsibility for management of all activities at an incident

- ensure that the Incident Commander conducts an initial size-up and risk assessment of the incident scene before beginning interior fire fighting operations

- train fire fighters to communicate interior conditions to the Incident Commander as soon as possible and to provide regular updates

- ensure that the Incident Commander establishes a stationary command post, maintains the role of director of fireground operations, and does not become involved in fire-fighting efforts

- ensure the early implementation of division / group command into the Incident Command System

- ensure that the Incident Commander continuously evaluates the risk versus gain when determining whether the fire suppression operation will be offensive or defensive

- ensure that the Incident Commander maintains close accountability for all personnel operating on the fireground

- ensure that a separate Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed at each structure fire

- ensure that crew integrity is maintained during fire suppression operations

- ensure that a rapid intervention crew (RIC) / rapid intervention team (RIT) is established and available to immediately respond to emergency rescue incidents

- ensure that adequate numbers of staff are available to immediately respond to emergency incidents

- ensure that ventilation to release heat and smoke is closely coordinated with interior fire suppression operations

- conduct pre-incident planning inspections of buildings within their jurisdictions to facilitate development of safe fireground strategies and tactics

- consider establishing and enforcing standardized resource deployment approaches and utilize dispatch entities to move resources to fill service gaps

- develop and coordinate pre-incident planning protocols with mutual aid departments

- ensure that any offensive attack is conducted using adequate fire streams based on characteristics of the structure and fuel load present

- ensure that an adequate water supply is established and maintained

- consider using exit locators such as high intensity floodlights or flashing strobe lights to guide lost or disoriented fire fighters to the exit

- ensure that Mayday transmissions are received and prioritized by the Incident Commander

- train fire fighters on actions to take if they become trapped or disoriented inside a burning structure

- ensure that all fire fighters and line officers receive fundamental and annual refresher training according to NFPA 1001 and NFPA 1021

- implement joint training on response protocols with mutual aid departments

- ensure apparatus operators are properly trained and familiar with their apparatus

- protect stretched hose lines from vehicular traffic and work with law enforcement or other appropriate agencies to provide traffic control

- ensure that fire fighters wear a full array of turnout clothing and personal protective equipment appropriate for the assigned task while participating in fire suppression and overhaul activities

- ensure that fire fighters are trained in air management techniques to ensure they receive the maximum benefit from their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA)

- develop, implement and enforce written SOPS to ensure that SCBA cylinders are fully charged and ready for use

- use thermal imaging cameras (TICs) during the initial size-up and search phases of a fire

- develop, implement and enforce written SOPs and provide fire fighters with training on the hazards of truss construction

- establish a system to facilitate the reporting of unsafe conditions or code violations to the appropriate authorities

- ensure that fire fighters and emergency responders are provided with effective incident rehabilitation

- provide fire fighters with station / work uniforms (e.g., pants and shirts) that are compliant with NFPA 1975 and ensure the use and proper care of these garments.

Additionally, federal and state occupational safety and health administrations should:

- consider developing additional regulations to improve the safety of fire fighters, including adopting National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) consensus standards.

Additionally, manufacturers, equipment designers, and researchers should:

- continue to develop and refine durable, easy-to-use radio systems to enhance verbal and radio communication in conjunction with properly worn SCBA

- conduct research into refining existing and developing new technology to track the movement of fire fighters inside structures.

Additionally, code setting organizations and municipalities should:

- require the use of sprinkler systems in commercial structures, especially ones having high fuel loads and other unique life-safety hazards, and establish retroactive requirements for the installation of fire sprinkler systems when additions to commercial buildings increase the fire and life safety hazards

- require the use of automatic ventilation systems in large commercial structures, especially ones having high fuel loads and other unique life-safety hazards.

Additionally, municipalities and local authorities having jurisdiction should:

- coordinate the collection of building information and the sharing of information between building authorities and fire departments

- consider establishing one central dispatch center to coordinate and communicate activities involving units from multiple jurisdictions

- ensure that fire departments responding to mutual aid incidents are equipped with mobile and portable communications equipment that are capable of handling the volume of radio traffic and allow communications among all responding companies within their jurisdiction.

INTRODUCTION

On June 18, 2007, nine male career fire fighters (the victims), aged 27 to 56, died when they became disoriented in rapidly deteriorating conditions inside a burning commercial furniture showroom and warehouse facility. At least seven other municipal fire fighters and two mutual aid fire fighters barely escaped serious injury.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Division of Safety Research, Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, learned of the incident on June 19, 2007 through the national news media. On June 19, 2007, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) notified NIOSH of the fatalities. That same day, a Safety Engineer and a General Engineer from NIOSH traveled to South Carolina to initiate an investigation of the incident. The NIOSH investigators traveled to the incident site and met with representatives of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), South Carolina State Law Enforcement Division (SLED), and South Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Administration (SC-OSHA). The NIOSH investigators were on-site June 20-22, and the NIOSH General Engineer returned June 24th to work with representatives of NIST to collect data related to the structure’s constructiona for the NIOSH investigation and for a comprehensive fire reconstruction model. Note: The NIST Building and Fire Research Laboratory is developing a computerized fire model to aid in reconstructing the events of the fire. When completed, this model will be available at the NIST websiteexternal icon: http://www.nist.gov/el/. (Link Updated 1/17/2013)

a The fire completely destroyed the structure and the sheet metal roof was removed at the direction of ATF before NIOSH and NIST were allowed access to the structure. Consequently, detailed information on the construction was not available and NIOSH and NIST frequently relied on photographs of the structure after the fire.

On July 9, 2007, three NIOSH investigators (Safety Engineer, General Engineer, and Safety and Occupational Health Specialist), along with representatives of NIST, returned to South Carolina. Meetings were conducted with the Fire Chief; Assistant Chief; the city’s Director, Safety Management Division; and the city’s Workers’ Compensation administrator.

During the weeks of July 9-13, July 16-20, and August 27-31, 2007, interviews were conducted with officers and fire fighters who were on-duty and dispatched to the incident scene, as well as fire fighters who were off-duty and came to the scene to offer assistance. Fire fighters from two mutual aid departments were also interviewed during these times. NIST representatives participated in many of the NIOSH interviews to collect information for their computerized fire model.

During the course of the ensuing investigation, the NIOSH investigators met with chief officers and fire fighters from the initial responding department, two local mutual aid departments, NIST staff, the county coroner, the county emergency response dispatch center staff, city building inspectors, city water system officials, representatives of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) labor union, U.S. Fire Administration staff, ATF, and representatives of the city’s Fire Review Team (FRT).

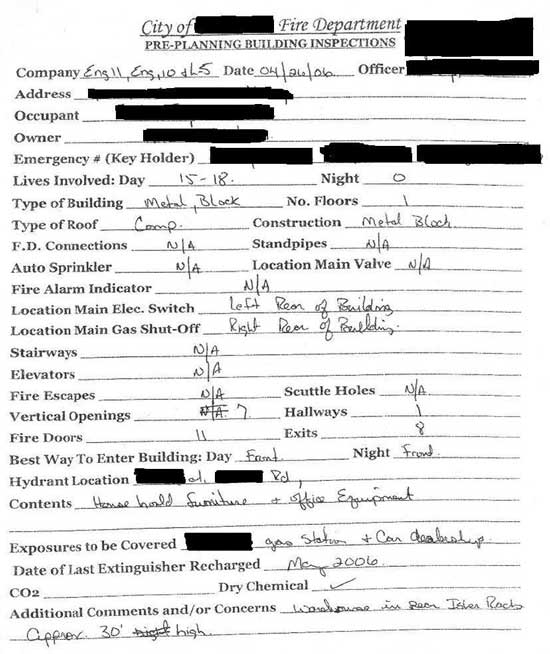

NIOSH investigators reviewed some departmental standard operating procedures,b the victims’ training records, chief officers’ training records, and floor plans and photographs of the structure. Photographs were obtained from a number of sources including NIOSH, NIST, the city police department, the FRT and national media.c NIOSH investigators visited the city’s fire training academy, met with the training officer, and reviewed the training schedule (see Appendix I). The department’s maintenance and repair facility (for in-house maintenance and repair of fire apparatus, equipment, and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA)) was visited and maintenance records were reviewed. An independent inspection report for one of the apparatus involved in the incident, that had been contracted for by the city, was reviewed (see Appendix II). The city’s fire and police dispatch center was visited as well as the dispatch center for the first responding mutual aid department. Other sources of information used in this investigation include state and federal OSHA regulations, NFPA standards, fire department pre-plan information (see Appendix III), coroner’s reports, copies of the fireground radio transmissions provided by the city legal department, a transcript of the dispatch audio records provided by the FRT, and the FRT Phase I and Phase II reports.1,2

b NIOSH investigators reviewed two Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) provided to NIOSH: “Standard Operating Procedures Engine Company 2” (undated) and “Fire Department Policies and Procedures Manual” dated July 25, 2005. The city reported that there were additional SOPs in place at the time of the incident.

c Some photographs used in this NIOSH report have been altered to remove names, faces and other identifiers.

NIOSH contracted with a leading expert in personal protective clothing to evaluate the clothing and personal protective equipment worn by the victims (see Appendix IV). This evaluation took place on August 29, 2007. The evaluation site and handling of the evidence materials was coordinated with the assistance of the county coroner’s office and the city police department. The PPE evaluation was witnessed by representatives of NIOSH, NIST, the FRT, the county coroner’s office, the city police department, and the state fire marshal’s office.

The lead NIOSH investigator participated in a meeting convened by the U.S. Fire Administration on September 20, 2007 to discuss the status of ongoing investigations and share information not of a confidential nature. This meeting consisted of representatives of the U.S. Fire Administration, ATF, the FRT, the county coroner, NIST and NIOSH. The lead NIOSH investigator participated in a similar meeting convened by the FRT on December 18, 2007. This meeting consisted of representatives of the FRT, ATF, the county coroner, NIST, and NIOSH.

Safety and Health Regulations

South Carolina is one of 26 states and territories which administers its own occupational safety and health program through an agreement with the U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The South Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Administration (SC-OSHA) has jurisdiction over private and public sector employers and employees within the state. The state occupational safety and health act requires employers to provide their employees with a safe and healthy worksite which is free of hazards which may cause injuries and illnesses to workers. South Carolina has adopted the federal OSHA Standards verbatim, with a few exceptions.3 Most notably, South Carolina OSHA has revised the federal OSHA Respiratory Protection Standard paragraph 1910.134(g)(4)(ii), commonly known in the fire service as the “two in – two out” rule, to allow fire fighters to enter immediately-dangerous-to-life-or-health (IDLH) atmospheres with only one fire fighter located outside the IDLH atmosphere until additional fire fighters arrive, provided certain conditions are met.

Following the fatal fire, SC-OSHA cited the fire department for several alleged violations and assessed penalties.4 The fire department and city contested these findings and SC-OSHA and the city reached a settlement in which the fire department was cited for two violations, an inadequate fire department incident command system and failure to ensure use of personal protective equipment by some fire fighters at the incident.5 SC-OSHA also cited the furniture store employer for locked exit doors, fire doors not operating properly, and not implementing an emergency action plan at the store.4

Fire Department

At the time of the incident, the career fire department was an ISOd Class I rated department with 19 fire companies located throughout the city. The fire department serves a population of approximately 106,000 in a geographic area of about 91 square miles. In June 2007 the fire department consisted of approximately 240 uniformed fire fighters and fire officers. The department operated 16 engine companies and 3 ladder truck companies at 14 stations in the city. Each apparatus was staffed with four fire fighters but routinely operated with three fire fighters per apparatus (a captain, engineer, and fire fighter), depending on the staffing available each shift. The standard work shift was 24 hours on-duty and 48 hours off-duty, with fire fighters assigned to one of three rotating shifts. Each shift was supervised by an Assistant Chief. On the day of the incident, the department had 61 fire fighters, 4 Battalion Chiefs and an Assistant Chief working on-duty. Note: At the time of the incident, the fire department did not have a safety officer position and a safety officer was not designated at the incident. Since then, the fire department has hired a full-time permanent safety officer.

d ISO is an independent commercial enterprise which helps customers identify and mitigate risk. ISO can provide communities with information on fire protection, water systems, other critical infrastructure, building codes, and natural and man-made catastrophes. Virtually all U.S. insurers of homes and business properties use ISO’s Public Protection Classifications (PPC) to calculate premiums. In general, the price of fire insurance in a community with a good PPC is substantially lower than in a community with a poor PPC, assuming all factors are equal. ISO’s PPC program evaluates communities according to a uniform set of criteria known as the Fire Suppression Rating Schedule (FSRS). The FSRS has three main parts – fire alarm and communications (10%), the fire department (50%), and water supply (40%). The FSRS references nationally recognized standards developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the American Water Works Association. Rated fire departments are classified 1 through 10 with Class 1 being the best rating a fire department can receive. More information about ISO and their Fire Suppression Rating Scheduleexternal icon can be found at the website http://www.isogov.com/about/.

The fire department utilized the 911 dispatch center operated by the municipal police department (PD). The local county also maintains an emergency communications / dispatch center and provides communications for two small fire departments. Some mutual aid fire departments within the county maintain their own dispatch centers.

The first mutual aid department to respond to the scene was a career department that employs 60 fire fighters and officers. It maintains four stations and serves a population of approximately 24,000 residents in an area of approximately 30 square miles. Jurisdictional boundaries between this mutual aid department and the municipal department were intermingled. Adjoining properties in the same block could be in different jurisdictions. This led to incidents where a department would be the first to arrive at a working fire outside its jurisdiction.

The second mutual aid department to respond to the scene was a combination department with 44 fire fighters that serves a rural population of 14,000.

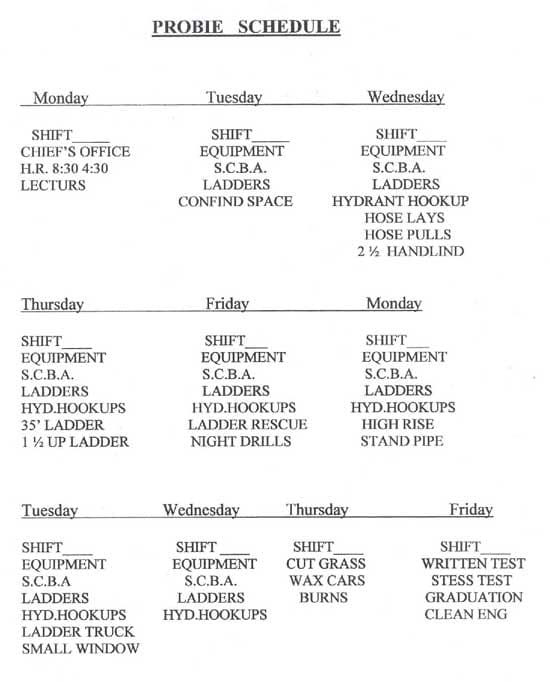

Training

In South Carolina, it is up to the local fire chief to decide what level of training is required for fire department personnel to obtain in order to meet SC-OSHA training requirements. At the time of the incident, this municipal fire department required fire fighters to receive basic training to at least Fire Fighter I certification from the South Carolina Fire Academy or some other source. While the South Carolina Fire Academy is accredited by the International Fire Service Accreditation Congress to provide a number of NFPA level courses, at the time of the incident, the fire department recognized training from sources other than the South Carolina Fire Academy as meeting their basic certification requirements. Note: Basic fire fighter certification required by the fire department at the time of the incident did not meet NFPA 1001, Standard for Firefighter Professional Qualifications. 6

Once hired, the recruits were assigned to the department’s training center for 10 days of hands-on training after which the new fire fighters were assigned to companies throughout the city. The department’s training focused on equipment use, SCBA use, ladder drills, hydrant hookup, hose lays, hose pulls, rescue drills, and live-burn exercises (see training schedule – Appendix I ). A training officer supervised the recruit training and oversaw the department’s training program. Individual companies normally trained from 0930 to 1130 hours each day with each company’s captain responsible for the training. Training on hydrant location and hook-up was done once per month. Driver / operator training was mainly on-the-job hands-on training. Individual fire fighters could request to receive driver / operator training. The request would then be reviewed and approved through the department’s chain of command.

Training records provided by the city for the nine victims consisted of verification of the weekly in-station training, certificates indicating training on subjects such as National Incident Management System (NIMS), weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and emergency medical services – medical first responder. SCBA facepiece fit test records were also provided. Training records for the chief officers were provided, consisting mainly of copies of National Incident Management System (NIMS) training certificates.

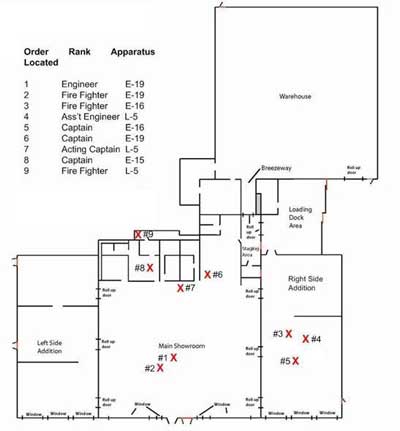

Victims

Note: Throughout this report, the 9 victims are identified by the order in which they were located at the scene, identified by the County Coroner, removed from the structure and transported. The following table provides information on each victim.

| Victims (Order located) |

Rank

|

Apparatus

|

Age

|

Experience

(yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

Engineer |

Engine 19

|

37

|

9

|

|

2

|

Fire fighter |

Engine 19

|

56

|

32

|

|

3

|

Fire fighter |

Engine 16

|

46

|

2

|

|

4

|

Assistant Engineer |

Ladder 5

|

27

|

1.5

|

|

5

|

Captain |

Engine 16

|

49

|

29

|

|

6

|

Captain |

Engine 19

|

48

|

30

|

|

7

|

Acting Captain |

Ladder 5

|

40

|

12.5

|

|

8

|

Captain |

Engine 15

|

34

|

11.5

|

|

9

|

Fire fighter |

Ladder 5

|

27

|

4

|

Equipment and Personnel

The municipal fire department initially responded to the alarm with 3 apparatus and 9 fire fighters including Engine 11 (E-11 acting captain, acting engineer and fire fighter), Engine 10 (E-10 captain, acting engineer and fire fighter), Ladder 5 ( L-5 acting captain, engineer (assistant engineer), and fire fighter), a battalion chief (BC-4) and an Assistant Chief (AC). Note: Fire department procedures stated that where structures were 5 stories or less in height, the first alarm assignment would be 2 engines, 1 ladder truck, and a Battalion Chief. For structures over 5 stories in height, the first alarm assignment would be 3 engines, 1 ladder truck, a Battalion Chief and the Assistant Chief. Once on-scene, the Incident Commander could request additional resources as deemed necessary. Procedures also stated that a confirmed report of “smoke showing” would automatically send an additional engine. When a ranking officer arrived on-scene, that officer automatically became Incident Commander.

Engine 16 (E-16 captain, engineer, and fire fighter) was dispatched after BC-4 (the initial Incident Commander (IC)) radioed dispatch to confirm smoke was showing at the incident site as per department procedures. E-16 was designated as the third-due engine responding to all structure fires in the western district (where the incident occurred) if not assigned on the initial dispatch. Chief Officers requested Engine 15 (E-15), Engine 12 (E-12), Engine 19 (E-19), Engine 6 (E-6), Engine 3 (E-3), Engine 13 (E-13), Engine 9 (E-9), and Ladder 4 (L-4) as the incident escalated. Additional responders included the Battalion Chief from the neighboring district (BC-5) and the Battalion Chief of training (BC-T). A large number of off-duty officers and fire fighters also responded to the incident scene. Some of the off-duty fire fighters responded with turnout gear, others did not.

Only the units directly involved in the operations preceding the fatal event are discussed in this report. The activities of the additional mutual aid departments that were dispatched after the structure collapsed are not addressed by this report.

Timeline

Note: This timeline is provided to set out, to the extent possible, the sequence of events as the fire departments responded. The times are approximate and were obtained from review of the dispatch audio records, witness interviews, photographs of the scene and other available information. In some cases the times may be rounded to the nearest minute, and some events may not have been included. The timeline is not intended, nor should it be used, as a formal record of events.

The response, listed in order of arrival (time approximate) and events, include:

1907 hours

- Dispatch for possible fire behind furniture store

1909 hours

- BC-4, E-10, E-11, L-5 enroute

- BC-4 confirms smoke showing while enroute

- E-10, L-5, E-16 acknowledge hearing BC-4 confirm fire

- AC enroute

1910 hours

- E-16 enroute as third-due engine

- E-15 relocates to western district

- BC-4 arrives on scene and reports trash fire at side of building.

- BC-4 radios for E-10 to come down side of building

1911 hours

- Assistant Chief (AC) on scene

- E-10 and E-11 on scene

1912 hours

- AC radios for E-16 to come inside building when they arrive on-scene.

- (Showroom clear with no fire/smoke showing)

- Ladder 5 on scene

- Fire Chief (enroute) radios E-15 to relocate to Station 11

- AC radios dispatch to send Engine 12

- BC-4 radios Car 2 and says he knows fire is inside building

- Engine 12 dispatched to scene

1913 hours

- BC-4 radios E-12 that he needs E-12 to lay a supply line to E-10

- E-11 acting captain radios “I need an 1 ½” inside this building”

- (Door connecting showroom to loading dock was opened by AC showing heavy fire in loading dock)

- AC radios E-15 to “come on”

- AC radios E-15 and says to bring 1 ½” hose line inside to right rear of building

- E-6 begins relocating to the west side

1914 hours

- AC radios BC-4 and says fire is inside the rear of the building and moving towards the showroom

- AC radios dispatch to send E-6

- E-6 dispatched to scene

- Fire Chief radios dispatch to send E-19 and have E-6 relocate to Station 11

1915 hours

- AC radios E-16 to bring 2 ½” hose line in front door

- E-16 radios AC to confirm assignment

- E-16 on-scene

1916 hours

- L-5 engineer and L-5 fire fighter both radio E-11 to charge line (1 ½” line pulled by L-5 / E-11 crews)

- E-19 enroute

- L-5 again requests E-11 to charge hose line

- Fire Chief on scene

1917 hours

- E-12 on scene – assigned to lay supply line to E-10

- E-15 on scene

1919 hours

- Fire Chief radios E-6 and tells them to come to scene and come in front door

- E-6 responds they are enroute

- Fire Chief radios dispatch to call the power company

- E-16 captain radios “charge that 2 ½”

1920 hours

- E-11 engineer radios the E-11 acting captain to see if he wants the 2 ½” hose line charged.

- AC replies “not until the supply line is charged”

- E-19 on scene

- E-12 radios E-10 … “water coming 10”

- E-12 engineer radios dispatch that the police department is needed because cars are running over hoses. Dispatch replies that the police department is enroute

1921 hours

- AC radios E-16 engineer – “16, what about that supply line?” E-16 engineer replies he is looking for a hydrant.

- E-6 on scene

1922 hours

- E-11 engineer radios E-16 that tank water is down to half-full

- E-16 engineer replies he is looking for hydrant

1924 hours (see Photo #1)

- Battalion Chief 5 (BC-5) on scene

- Fire Chief radios E-12 to boost water pressure on supply line by 50 pounds

- E-12 acknowledges

- AC radios.. “We need that 2 ½” (referring to 2 ½” hoseline off E-11)

- E-3 is relocated to Station 16/19

- Mutual aid department # 1 on-scene

1925 hours

- E-10 radios that tank water is down to one-quarter full

- Fire Chief radios E-12 to boost supply water pressure to E-10 by 50 more pounds

- E-12 acknowledges

- Mutual aid department # 1 radios the fire department with no response

1926 hours

- E-16 engineer radios that “water coming”

- Dispatch radios Fire Chief and informs him that dispatch has received a phone call from a civilian saying he is trapped at the rear of the building

- Fire Chief acknowledges

1927 hours

- Inaudible radio traffic – possibly “lost inside” or “trapped inside”

- Fire Chief radios AC and says that the warehouse door has been opened and a 2 ½” hose line is in operation. Fire Chief also asks about the rescue attempt of the trapped civilian and tells AC to do what he can do.

- Dispatch radios AC to inform him that the trapped civilian is banging on exterior wall with a hammer

1928 hours

- AC radios for E-11 and gets no response. Note: This may be when the AC is looking for fire fighters to assist with rescue of the civilian and mutual aid fire fighters are pressed into action.

1929 hours

- Broken radio traffic of fire fighter in distress asking “which way out” then “everyone out”

1930 hours (see Photo # 2)

- E-11 radios that 2 ½” hose line is charged

- Several different fire fighters in distress radio “need some help out,” “need help getting out,” also “lost connection with the hose”

- AC radios Fire Chief that they are attempting to free civilian trapped in warehouse

1931 hours – 1934 hours (see Photo #3)

- More broken radio traffic from fire fighters in distress

- L-5 repositioned to D-side by off-duty fire fighters

- Fire Chief asks for E-3 to come to scene and lay supply line to L-5

- BC-5 reports civilian is out of building

- E-16 engineer radios dispatch that police department is needed to prevent traffic from running over supply line.

- FF calls Mayday

- Fire Chief asks AC “is everyone out?” AC responds the civilian is out

- Fire Chief radios AC to make sure his people are accounted for.

- E-15 FF exits building (out of air) – reports he didn’t call the Mayday

- Fire Chief radios “who called Mayday”

- Fire Chief radios “…we need to vacate the building”

- Dispatch tells Fire Chief that the L-5 engineer emergency button (on radio) has been activated

- Fire Chief radios for E-15 captain with no response

- E-15 FF changes air cylinder and goes back inside

1935 hours – 1936 hours (see Photos # 4, # 5, and # 6)

- Front windows knocked out

- E-6 crew (captain, engineer, and FF) along with E-15 engineer and FF exit showroom

- Fire Chief orders mutual aid crew to search for missing fire fighters

- Fire Chief continues to radio for E-15 captain and crew with no response

- Fire Chief instructs everyone else to stay off radio

- Conditions at front of showroom change dramatically – turbulent thick dark smoke rolls out windows

1937 hours

- Fire Chief continues to radio for E-15 captain and crew with no response

- E-13 is dispatched to scene

- E-7 relocates to Station 13

- Fire rolls out windows at front of showroom

1938 hours (see Photos # 7 and # 8)

- Mutual aid crew exits building

- Fire Chief continues to radio for E-15 captain and crew with no response

- Fire Chief radios for everyone to abandon the building

- Training Chief (BC-T) radios for E-15 captain

- BC-T radios E-16 engineer to boost water supply pressure to E-11.

1939 hours

- AC radios E-16 to “give me some more water”

- BC-T also radios E-16 for more water pressure

- E-16 engineer acknowledges and water pressure is boosted to 200 psi

1940 hours

- E-3 on scene

- Mutual Aid Department # 2 enroute to lay water supply line to L-5

1942 hours

- BC-T continues to radio for E-15 captain (no response)

- Fire Chief radios that no one is to go inside

- E-13 on scene

1943 hours

- Fire Chief asks if everyone is out of front

- BC-T radios E-16 engineer that he needs more water pressure. Engineer responds that the entire hose bed has been stretched out plus two sections of 3” hose. Additional radio communications about civilian vehicle traffic driving over the supply line.

- BC-T radios E-16 engineer and says “I need all you can give me!”

1944 hours

- AC radios dispatch to call the city water department to increase water pressure in the area.

- Fire Chief radios for E-15 captain

- E-3 engineer radios that water is coming (water supply established to L-5)

Additional crews continued to arrive on-scene and contributed to the fire suppression efforts. Engine 13 began laying a supply line to L-5 at 1947 hours. The Fire Chief radioed dispatch to send Ladder 4 to the scene at 1948 hours. The Fire Chief radioed dispatch and requested that the Mayor be notified at 1950 hours. A portion of the roof over the right side of the showroom collapsed causing the front façade to begin collapsing at 1951 hours. Eventually, almost the entire roof over the main showroom and the right side addition collapsed. Ladder 4 was put into operation in the front parking lot at approximately 2005 hours. The fire was brought under control after 2200 hours. Recovery operations continued until after 0400 hours the next morning.

Personal Protective Equipment

The fire department issued each fire fighter a full set of black turnout gear and station uniforms when they were hired and sent to the recruit training class. The department issued helmets, hoods, gloves, and boots. The Chief Officers (Battalion Chief rank and higher) wore a set of brown turnout gear from a different manufacturer. At the time of the incident, each fire fighter was allowed to purchase and wear his own turnout gear, or bring their gear from other departments they served in, if they desired, so long as it met the requirements of the department.

Following the incident, the personal protective equipment (PPE – turnout clothing, SCBA, radio, hand tools, etc) worn by each of the nine victims was secured by the city police department. On August 29, 2007, the PPE was examined in detail by a personal protective clothing expert contracted by NIOSH. The PPE was examined, documented and photographed through a systematic process. The county coroner’s office coordinated the PPE examination at the request of NIOSH. Representatives of NIOSH, NIST, the FRT, the county coroner’s office, the city police department, and the state fire marshal’s office were present during the examination. Each victim’s PPE was severely damaged by fire and heat exposure due to the length of time it took to locate and recover the victims. The evaluation indicated melting of polyester station uniforms (non-NFPA 19757 compliant) in the areas where the turnout clothing was degraded by the fire exposure. The PPE examination also identified examples where turnout gear was not being properly worn such as turnout coat collars not fully extended upward and helmet ear flaps not deployed. A summary of the complete PPE inspection is contained in Appendix IV. A copy of the complete PPE inspection report is available upon request from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program.

The city fire and police departments utilized a type-2 trunked radio system (computer-aided) that automatically assigned radio frequencies as needed to different “talk groups.” Each apparatus riding position was assigned a radio so that each on-duty fire fighter had access to a radio. Each radio contained an emergency notification button that, when activated, would send a signal to the dispatch center with the radio’s identity. On the day of the incident, radios were available, but at least one fire fighter did not carry his assigned radio. The county in which this incident occurred maintained its own dispatch center for emergency medical services (EMS) and the smaller outlying volunteer fire departments. Some smaller fire departments operated as public service districts (PSDs) and operated their own dispatch centers. Thus not all fire departments who were on scene could communicate directly with the city fire department due to the multiple radio systems in place.

Apparatus and Equipment Maintenance

The fire department operated a maintenance and repair facility at one of the stations, where in-house maintenance was performed on all fire apparatus, equipment and SCBA. Annual pump flow testing was conducted and recorded. During the NIOSH investigation, interviewed fire fighters reported a number of recurring maintenance problems on apparatus and power equipment to the NIOSH investigators.

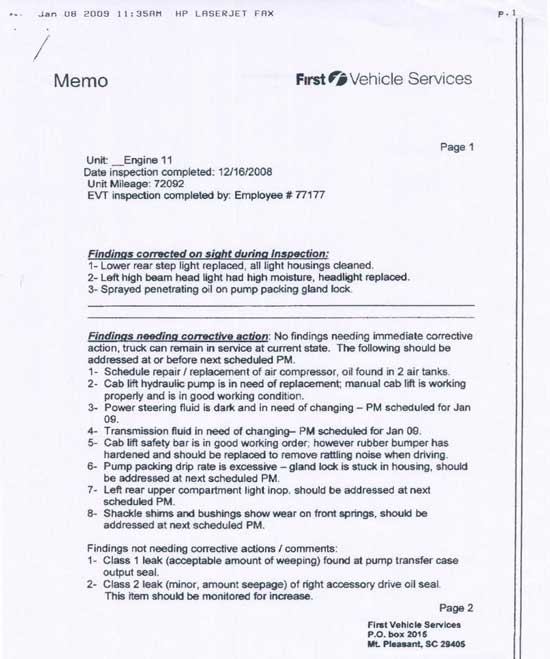

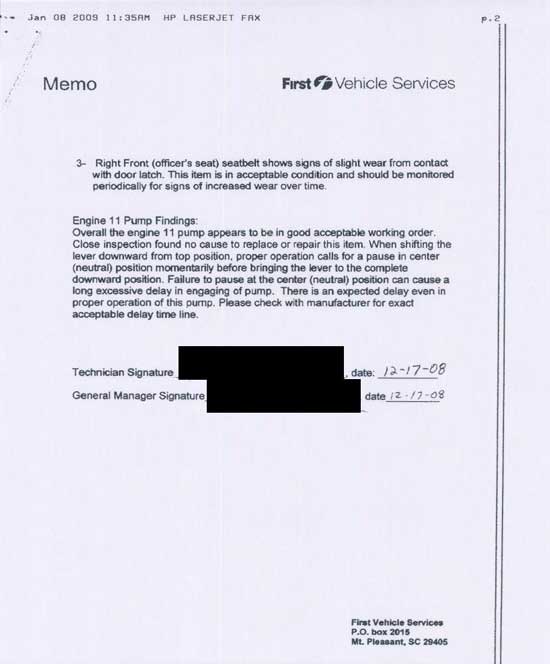

During the NIOSH investigation, fire fighters reported during interviews that Engine 11 (E-11) required specific procedures to engage the pump. When interviewed by NIOSH investigators, the maintenance supervisor reported that E-11 had a hydraulic transmission and a non-electric pump, and if the engine was not throttled to full throttle before the pump was engaged, the pump would not discharge at full capacity. The city reported that there were no records or reports of operational issues with E-11 prior to this event, and that daily equipment checks were performed. In December 2008, the city contracted with a nationally recognized company to conduct independent testing and evaluation of E-11. The city indicated that no changes had been made to Engine 11 since the fire. A copy of the December 16, 2008 inspection report was provided to NIOSH for review (Appendix II). The results of this testing and evaluation indicated that Engine 11 was generally in good acceptable working order with 3 maintenance findings that were corrected during the inspection, and 8 findings needing corrective action. In addition, the report highlighted findings of the Engine 11 pump inspection. The report reads, “When shifting the [pump] lever downward from top position, proper operation calls for a pause in center (neutral) position momentarily before bringing the lever to the complete downward position. Failure to pause at the center (neutral) position can cause a long excessive delay in engaging of pump. There is an expected delay even in proper operation of this pump. Please check with manufacturer for exact acceptable delay time line.”

During the NIOSH investigation, fire fighters reported to NIOSH investigators that the fire department’s procedure was to refill cylinders when the pressure dropped to 1500 psi which is well below the required 90% level found in the OSHA Respirator Standard8 and NFPA 18529 (1500 psi is 68% of full cylinder pressure or 2216 psi). NIOSH investigators examined a small number of SCBA cylinders in service on city fire apparatus and did find some with cylinder pressures below 2000 psi.

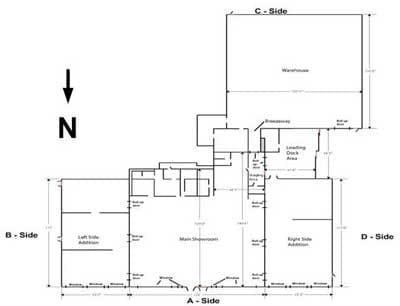

Structure

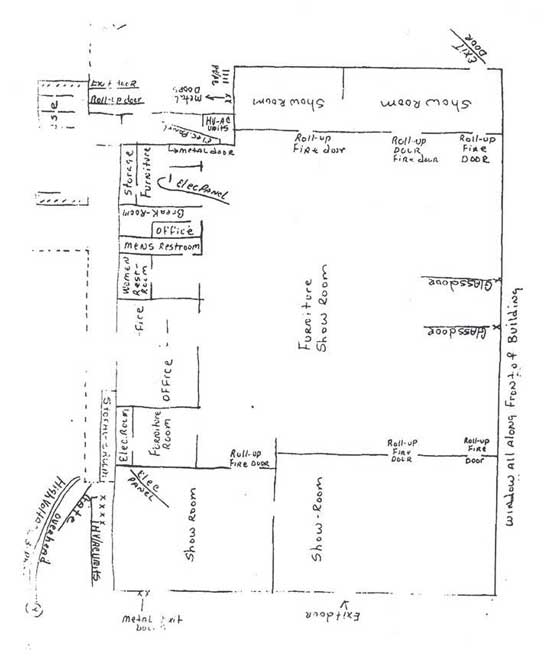

The structure involved in this incident was a one-story, commercial furniture showroom and warehouse facility totaling over 51,500 square feet that incorporated mixed-construction types. The structure was non-sprinklered. The facility had been renovated and expanded a number of times over the past 15 years. The original structure was constructed in the 1960’s as a 17,500 square foot grocery store with concrete block walls and lightweight metal bar joists (metal roof trusses) supporting the roof to create an open floor plan. After being converted to a furniture retail store, the original structure was expanded by adding a 6,970 square foot addition on the right side (D-side) in 1994 and a 7,020 square foot addition to the left (B-side) in 1995. Both additions were attached to the original exterior walls and consisted of steel beams supporting the walls and roof. To provide access between the original structure and the two additions, the exterior walls on the B and D sides of the original structure were each penetrated in 3 locations to form six 8’ X 8’ openings that were equipped with metal roll-up fire doors. These fire doors were equipped with fusible links designed to automatically close the doors in the event of a fire. In 1996, a 15,600 square foot warehouse was added to the rear of the main showroom. The main showroom and the warehouse were connected by an enclosed wood-framed loading dock of approximately 2,250 square feet. Double metal doors connected the rear of the right-side addition to the loading dock area. These metal doors swung outward (opened into the loading dock). Additional access to the loading dock area was available from the rear of the original structure. (See Diagram 1)

At the time of the incident, the showroom included painted sheet-metal siding on the B and D side exterior walls with a combination of sheet metal and concrete block in the rear (C-side) and a front masonry and block façade (at the A-side). The roof over the main showroom (original structure) was constructed of sheet-metal roof decking covered by foam insulation and a weather membrane. Both right and left showroom additions included roofs constructed of sheet metal roof decking over fiber glass insulation. The fire caused extensive damage to the roof structure, making an analysis of the roof construction difficult.

The warehouse was a free-standing, clear-span structure with sheet-metal walls and roof. Both structures contained concrete floors. The main showroom measured 9 feet from the floor to a suspended drop ceiling and approximately 14 feet to the roof, creating almost 5 feet of void space above the suspended ceiling. The warehouse measured 29 feet from the floor to the roof. The warehouse contained rows of metal storage shelving that contained a variety of furniture items including couches, chairs, mattresses, etc. (see Photo 9 showing storage racks in warehouse).

The roofs over the main showroom, the showroom additions on both the B and D sides of the structure, and the warehouse contained limited penetrations (ventilation ductwork, utilities, etc.). Thus there were limited openings for smoke and hot gases to escape naturally in the event of a fire.

According to city building officials, the property was annexed into the city in 1990. The original structure and the 3 additions were considered as 4 separate structures for code enforcement purposes. Separate permits were issued for the construction of the left and right side additions and the warehouse. City building officials indicated to NIOSH investigators that after the fire, the furniture store property was determined to be “non-code compliant” (not in compliance with applicable codes). Work had been performed on the loading dock area and the maintenance shop without permits between 1996 and 2005. Other code violations included the accumulation of trash outside the loading dock, large quantities of flammable liquids, solvents, and thinners in the loading dock area, and storage of furniture and flammable materials in non-permitted areas.

At the time of the incident, city ordinances required commercial structures over 15,000 square feet to be equipped with a sprinkler system. The original structure was grandfathered (exempt from this requirement) while the left and right additions (at the B and D-sides) did not meet the threshold requirement. Thus, since the store was considered as 4 separate structures, the facility had been exempt from sprinkler system requirements.

The structure had been inspected by the fire department on a number of occasions. In 1987, fire inspection duties were transferred from the fire department to the city with the last documented fire code inspection by the city in 1998. The fire department continued to perform periodic pre-plan inspections. A building pre-plan form obtained from the fire department dated April 26, 2006 noted that store contents were “household furniture and office equipment” and that the rear warehouse contained racks approximately 30 feet high (see Appendix III). The pre-plan form did not mention the large volume of furniture and flammable materials (fuel load) contained in the structure. It was reported to NIOSH investigators by fire fighters during interviews that trash from the furniture business, including packing materials, cardboard, broken furniture and other flammable materials, were routinely stored against the building near the loading dock on the west (D) side of the structure (see Diagram 2).

Weather

At the time of the incident, the temperature was approximately 86 degrees Fahrenheit (F) with a dew point of 72 degrees F and a relative humidity of 63 percent. The sky was partly cloudy with light winds blowing from the south up to 11 miles per hour.10

INVESTIGATION

The furniture store fire on June 18, 2007, was originally dispatched as a possible fire behind a commercial retail furniture store. The initial Incident Commander radioed dispatch that the fire was a “bunch of trash free-burning against the side of the structure.” The fire very rapidly grew into an incident of major proportions. (A computerized fire model will be available in the future from NISTexternal icon at http://www.nist.gov/el/). (Link Updated 1/17/2013)

Summary of Initial Sequence of Events

On June 18, 2007, at approximately 1907 hours, the fire department was dispatched to a possible fire behind a large commercial retail furniture store. Two engines (Engine 11 and Engine 10), one ladder truck (Ladder 5), and the Battalion Chief (BC-4) were dispatched per department procedures. The on-duty Assistant Chief (AC) was at Station 11 and responded to the scene. While enroute, BC-4 observed heavy dark smoke rising into the air and radioed dispatch that smoke was coming from the direction of the store. Per department procedures, this initiated the response of the third-due engine (Engine 16) to the scene.

BC-4 arrived on scene driving east to west, pulled past the store and drove down the alley to the loading dock located on the D-side of the structure. BC-4 observed fire burning from ground level to over the roofline outside of the covered loading dock. Note: The covered loading dock connects the front showroom area to the rear 15,600-square foot warehouse facility. BC-4 radioed dispatch that the fire was a “bunch of trash free-burning against the side of the structure.” The dispatcher asked the responding units if they heard BC-4’s report on the fire conditions. E-10, L-5, and E-16 acknowledged.

When the AC arrived on-scene, he parked in the parking lot in front of the main showroom right addition. The AC and BC-4 briefly discussed their observations and directed Engine 10 to back down the alley to the loading dock area. The AC entered the store through the main entrance located in the center of the front of the structure (A-side). The AC walked down the center of the showroom to the rear (in the original structure) then went back outside. He did not observe any smoke or fire in the main showroom. BC-4 drove his car to the front of the showroom and observed the AC coming out of the showroom’s main entrance. The AC remained at the front of the store while BC-4 returned to the D-side. Note: Departmental policy was that the highest ranking officer on-scene was the Incident Commander. Incident Command (IC) was never formally announced at this incident.

While the E-11 crew looked for a hydrant to establish water supply, the AC and the E-11 acting captain re-entered the main showroom. The AC radioed E-16 to come inside the front door when they arrived on scene. E-16 acknowledged. Ladder 5 (L-5) arrived on-scene at 1912 hours and pulled into the parking lot in front of the furniture store, facing east. BC-4 radioed the AC and informed him that the fire was now inside the structure. The AC radioed Dispatch and requested that Engine 12 (E-12) be sent to the scene. The Fire Chief advised the dispatcher to relocate Engine 15 (E-15) to Station 11. BC-4 radioed E-12 and instructed them to lay a supply line to E-10. E-12 acknowledged.

The Assistant Chief detected fire when he opened a door connecting the rear of the right showroom addition to the loading dock area. The E-11 acting captain radioed that he needed a 1 ½” hand line inside the building. When E-15 radioed that they had relocated to the west-side, the AC instructed E-15 to come to the scene. The AC also instructed E-15 to bring a 1 ½” hand line inside to the rear right-side of the structure. The AC radioed that the fire was inside the rear of the structure and was moving towards the showroom.

The E-11 acting captain went outside and met the L-5 crew pulling a 1 ½” hand line off E-11. The AC radioed dispatch and requested that Engine 6 (E-6) be sent to the scene. E-6 was dispatched at 1914 hours. The Fire Chief (enroute) radioed dispatch to change the assignment to have Engine 19 dispatched to the scene and have E-6 relocate to Station 11. E-16 radioed the AC to ask if they were to go to the rear of the building. The AC instructed E-16 to come to the front door and bring a 2 ½” hand line inside. The Fire Chief arrived on-scene at 1916 hours. Note: Beginning at approximately 1916 hours, the L-5 engineer is heard over the radio asking for the 1 ½” hose line from E-11 to be charged. Diagram 2 shows the location of Engine 10 and Engine 11 in relation to the structure and how the attack lines were deployed during offensive operations.

A mutual aid department noticed heavy black smoke in the area and self-dispatched to the scene. The fire had already spread to the warehouse when the mutual aid department arrived on-scene. After some discussion with the Fire Chief, the mutual aid department was assigned to the rear of the warehouse (C-side) to begin fire suppression.

The burning furniture quickly generated large volumes of smoke, toxic gases and soot that added to the fuel load. At approximately 1926 hours, a store employee called the city’s 911 Dispatch center and reported that he was trapped inside the back of the building. Note: The employee was actually working near the front of the warehouse opposite the covered loading dock (see Diagram 3.) The employee stated he was banging on the exterior wall with a hammer. The dispatcher told the employee to continue banging on the wall and to stay calm and stay as low to the floor as he could. The dispatcher radioed the Fire Chief and informed him of the situation. This information was also relayed to the city police dispatcher and a police officer on-scene verbally informed some fire fighters of the situation. The city Assistant Fire Chief and a Battalion Chief (BC-5) quickly instructed a crew of four fire fighters from the mutual aid department to initiate the rescue attempt on the B-side of the warehouse. This crew quickly located the point where the trapped civilian was banging on the exterior wall. They were able to cut through the exterior wall (metal siding) using a Haligan bar and axe. The fire fighters were able to safely extricate the civilian at approximately 1933 hours. The civilian employee rescue was announced over the radio. The mutual aid fire fighters assisted the employee to the front parking lot where he was checked by EMTs.

As the civilian was being rescued, the fire was extending into the main showroom. The fire quickly outgrew the available suppression water supply. The interior fire attack crews could not contain the spread of the fire. Note: At this point, three hose lines were inside the main showroom – the initial 1½ inch hose line, a 2½ inch hose line and a 1 inch booster line. All three hose lines were pulled off Engine 11 which was being supplied by Engine 16 through a single 2 ½ inch supply line approximately 1,850 feet long. Water supply from Engine 16 to Engine 11 was established at approximately 1926 hours. The interior crews from Engine 11, Ladder 5, Engine 16, Engine 15, Engine 19, and Engine 6 became disoriented as the heat rapidly intensified and visibility dropped to zero as the thick black smoke filled the showroom from ceiling to floor. The interior fire fighters realized they were in trouble and began to radio for assistance. At least one Mayday was called. Another fire fighter radioed that he had lost contact with the hose line and needed help. One fire fighter activated the emergency button on his radio.

Note: During this incident fire fighters experienced intermittent radio communication problems and interruptions. Audio transcripts of the fireground channel recorded multiple instances where fire fighters inside the structure (including some of the victims) transmitted over the radio but the transmissions were not heard or not understood. The first recorded transmission of a fire fighter requesting assistance occurred at approximately 1927 hours and transmissions requesting “we need help,” “lost connection with the hose,” and “Mayday” continued until at least 1934 hours. The first “Mayday” was recorded at approximately 1932 hours. The first recorded transmissions indicating chief officers were aware of the fire fighters calling for assistance was at approximately 1933 hours.

The Engine 6 crew and three fire fighters from E-15 were able to find the front door and exit the showroom. The front showroom windows were knocked out to improve visibility. Fire fighters, including two fire fighters from the mutual aid crew who extricated the trapped civilian, were sent inside to search for the missing fire fighters at approximately 1936 hours. The two mutual aid fire fighters made brief contact with two disoriented fire fighters just as the flammable mixture of gases and combustion by-products in the showroom ignited, filling the showroom with flames. The two mutual aid fire fighters lost contact with the two disoriented fire fighters and were driven outside by the intense heat and flames (see Photo 7). One of the rescuers received second degree burns on his face, neck, hands, and arms. An off-duty Battalion Chief and the Engine 6 engineer also entered the structure for a rescue attempt. They also were driven out by the rapid fire spread.

While fire fighters were known to be trapped inside, the number and their identities were not known. Interior fire fighters were caught in the rapid fire progression and nine fire fighters from the first-responding fire department were killed.

The operational details of each responding apparatus company are listed below. Per department procedures, chief officers requested additional apparatus as the need was identified.

Engine 10

The E-10 crew (consisting of a captain, engineer, and fire fighter) was in-transit returning to quarters when the fire dispatch came in. The crew could see smoke billowing from the incident scene as they pulled onto the highway and they heard BC-4 report over the radio a trash fire on the side of the structure. Note: E-10 and Ladder 5 are quartered at the same station. The fire fighters on E-10 and L-5 had switched positions so that another fire fighter could train on pumping E-10.

The AC and BC-4 were already on-scene when Engine 10 arrived. The AC directed E-10 to back down the alley parallel to the D-side of the store toward the loading dock. The crew observed smoke and flames inside the loading dock area and coming out an exhaust fan in the D-side wall. The E-10 captain pulled a booster line (1” red hose) and knocked down the outside trash fire while the E-10 fire fighter pulled a 1 ½” pre-connected hand line to the loading dock. BC-4 returned to the loading dock after meeting with the AC and observed fire burning inside the structure so he radioed dispatch to report that the fire was now inside the building. The E-10 captain decided to use the 1 ½” hand line for the interior attack. The E-10 engineer charged the 1 ½” hand line from the engine’s tank-water supply. Fire was readily visible inside the loading dock area as the E-10 fire fighter and captain advanced the hoseline inside the loading dock about 20 to 25 feet. At their furthest point of entry, the E-10 crew could just see the door connecting the enclosed loading dock to the showroom right-side addition. This area became fully involved in flames as the E-10 crew directed water onto the fire. The 60 gallons per minute (gpm) flow from their 1 ½” handline was insufficient to control the fire. According to the fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH, the flames appeared to float in the air and burned floor to ceiling. The water didn’t appear to have any effect on the fire so the crew started to retreat. Note: The E-10 crew told NIOSH investigators that the water pattern produced by their fog nozzle just pushed the flames around the room as they attempted to extinguish the fire. After the fire, at least 28 one-gallon cans of extremely flammable solvents were found inside the loading dock suggesting that at some point a vapor fire was burning inside the loading dock. As they were backing out, the hose either burst or was burned through by the fire. Water spraying from the ruptured hose aided the fire fighters (improved visibility and provided a protective water curtain) in locating the door and moving outside.

The E-10 engineer pulled some sections of 2 ½” supply line from E-10 out to the street to meet E-12 which had been assigned to provide a water supply line. When the E-10 attack crew exited the loading dock, they asked fire fighters from Engine 12 (E-12), just arriving on-scene, to repair the damaged 1 ½” hand line. The E-10 captain and fire fighter got the 1” booster line that they had previously pulled off E-10 and advanced the booster line to the loading dock door. The booster line did not have any effect on the fire so they backed the line out, switched back to the 1 ½” hand line (that had been repaired by the E-12 crew) and moved back inside the loading dock. By this time the Fire Chief was on scene. The Fire Chief came to the loading dock and yelled inside to tell the E-10 captain not to advance any further. A few seconds later, the Fire Chief ordered the E-10 crew to back outside and operate from the doorway. Note: The E-10 crew was inside the loading dock 3 times for a total of approximately 15 minutes. BC-4 observed that the fire had extended into the warehouse. BC-4 returned to the front of the building and asked the manager if he had keys for the warehouse at the rear of the loading dock. The manager said “no,” so BC-4 returned to the loading dock and directed the E-12 crew and off-duty fire fighters who had responded to the scene to cut through the warehouse’s roll-up door with a power saw. The crews experienced trouble with getting the saw to run properly and used axes and Haligan bars to open the warehouse doors. BC-4 also directed the E-10 crew to assist with opening up the warehouse. BC-4 then directed the E-10 crew to get a 2 ½” hand line with a stack-tipped nozzle from E-10 and pull it to the warehouse door. By this time, the warehouse was becoming well involved. A second 2 ½” hose line was later pulled from E-10 and put into operation.

BC-4 was able to look inside the warehouse and he observed a large amount of fire inside. BC-4 went back to the front of the building and directed 2 off-duty fire fighters to move Ladder 5 to the D-side and set it up for aerial water pipe operation. BC-4 also met with an off-duty captain and asked him to take over getting L-5 set up for operation. Note: This off-duty captain is also an Assistant Chief at a neighboring mutual aid fire department located about 20 miles away. A crew from the mutual aid department responded and the captain used this mutual aid crew to assist with establishing water supply to L-5 by supplying it with tank water and then stretching supply lines to Engine 12. Per department procedures, off-duty fire fighters are allowed to respond to working fires and become involved in fire suppression activities. Off-duty fire fighters are supposed to check in with the IC, give the IC their ID card or driver’s license, and get an assignment. The civilian owner of a small yellow frame building located next to the D-side of the furniture warehouse advised BC-4 that his building was full of vehicles, gasoline, oil, and other flammables (see Diagram # 2). BC-4 talked to the deputy chief of the first mutual aid department about the building and asked him to get a hand line to protect the yellow building. Once L-5 was put into operation at approximately 1944 hours, it also was used to protect this building.

Engine 11

The Engine 11 (E-11) crew (acting captain, acting engineer, and fire fighter) was in quarters at Station 11 and the engine was being washed when the fire dispatch was initiated. The AC and BC-4 were also at station 11. E-11 was the first due engine but Engine 10 was in the vicinity and arrived on-scene first. While enroute to the scene, the E-11 crew heard BC-4 radio that smoke was coming from the location of the furniture store. The original fire dispatch stated that the fire was at the rear, so E-11 turned left off the highway onto a side street and drove behind the building. The AC radioed for E-11 to come back to the front of the store and pull into the second entrance to the parking lot. E-11 circled around and turned right into the parking lot in front of the store just as E-10 backed down the alley on the D side. E-11 got on scene at 1911 hours just before BC-4 radioed that the fire was inside the structure. The acting captain on E-11 directed the E-11 acting engineer and fire fighter to lay a supply line to E-10. The E-11 fire fighter (suction man) started walking down the street looking for a hydrant. The E-11 fire fighter returned to E-11 before making a hydrant connection when Ladder 5 (L-5) arrived on-scene. The E-11 acting engineer was directed by the L-5 acting captain to reposition E-11 near the front door facing northeast.

The E-11 acting captain entered the main showroom doors and walked down the center aisle to the rear of the main showroom. The showroom was clear with no smoke visible inside. The AC had preceded the E-11 acting captain inside the showroom and the two walked into the right addition and walked to the rear of the right showroom addition. They both observed a small wisp of light smoke visible at ceiling level in this area. They were not immediately alarmed by this smoke and the AC opened the double door leading to the loading dock. They reported seeing lots of fire and smoke beyond the door. The AC attempted to pull the door shut but he could not shut the door due to the air rushing from the showroom toward the fire. The E-11 acting captain helped pull the door shut and the AC told the acting captain to get a 1 ½” hand line.

At 1913 hours, the E-11 acting captain radioed that he “needed an inch-and-a-half inside the building.” The E-11 acting captain then went outside and met the acting captain from Ladder 5 (L-5) pulling a 1 ½” preconnected hand line off E-11. They both pulled the 1 ½” pre-connected hand line through the center doors and down the center aisle. The hand line just reached the rear of the center showroom. The E-11 acting captain told the L-5 acting captain he was going to go outside to add in another section of hose. The E-11 acting captain added 5 more sections of 1 ½” hose (the second pre-connected hose line on E-11) and dragged it inside. The L-5 acting captain and L-5 fire fighter were at the nozzle at this time. The L-5 crew pulled the nozzle toward the rear of the right side addition (the line was still not charged at this point). The E-11 fire fighter entered the main showroom flaking more slack in the hose line. The E-11 acting captain asked him to go find out why they did not yet have water pressure on the 1 ½” hose.

After waiting a short time for water pressure, the E-11 acting captain went outside to find out why they still didn’t have water pressure. The E-11 acting captain and engineer were able to get the pump in operation by cycling the engine transmission to get the pump in gear. Note: Fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH stated that E-11 required specific procedures to engage the pump; an independent inspection of the apparatus confirmed these findings. On the day of the incident, the E-11 engineer was serving as the acting captain so E-11 was driven and operated by a fire fighter less experienced in its operation.

The E-11 acting captain then re-entered the structure. He had to don his facepiece and go on air because gray-colored smoke was starting to accumulate in the center of the showroom. Fire was still not visible in the showroom at this point.

The Engine 16 (E-16) captain and fire fighter entered the showroom with a 2 ½” hose line that was uncharged at this point. The E-11 acting captain told the E-16 captain he would go find out why the 2 ½” hose line was still uncharged. As he started to exit the showroom, the inside conditions changed very rapidly. The smoke turned very thick and grayish black. The E-11 acting captain had to find the 1 ½” hose and follow it outside. E-11 was still without a water supply at this point. After talking with the E-11 acting engineer about the water supply situation, the E-11 acting captain walked around to the loading dock area to look for the E-11 fire fighter.

While at the D-side, BC-4 asked the E-11 acting captain to help with setting up a 2 ½” hose line to the warehouse. Note: This 2 ½” hose line was pulled from E-10. The E-11 acting captain was just stepping up to the warehouse door when the Fire Chief ordered everyone out of the warehouse. The E-11 acting captain observed that the other fire fighters in this area had things under control so he went back to the A-side. When the E-11 acting captain returned to the front, fire was blowing out the front windows. He heard the Fire Chief give an order to evacuate. The E-11 acting captain got into the E-11 cab and sounded the airhorn 3 times for an evacuation signal.

Ladder 5

Ladder 5 (L-5) was the third apparatus to arrive on-scene and initially positioned in the parking lot in front of the furniture store just west of E-11. The L-5 crew included an acting captain (Victim # 7), an assistant engineer (Victim # 4) and a fire fighter (Victim # 9 – who had switched assignments with the E-10 fire fighter). Note: This fire department typically dispatches ladder trucks as extra manpower, and not for ventilation activities. The ladder trucks do not have their own pumps and must be supplied by an engine in order to flow a master stream.

The L-5 acting captain directed the E-11 acting engineer to reposition E-11 near the front door of the main showroom. It is assumed that the L-5 acting captain heard the E-11 acting captain radio for a hand line inside the structure so the L-5 crew started to pull a 1 ½” preconnected hand line off of E-11. When the L-5 crew took this hand line inside, they met the E-11 acting captain coming outside to get a hose line. The L-5 crew took the 1 ½” hose line to the rear of the right-side addition (after the E-11 acting captain added additional sections to the hose line) and after some delay in getting water, advanced into the loading dock through the double doors connecting the showroom to the loading dock. This was the last confirmed location of the L-5 crew.

Between approximately 1932 and 1934 hours, L-5 was repositioned from the front of the showroom to the D-side by off-duty fire fighters who had responded to the scene. Fire fighters from a mutual aid department along with off-duty fire fighters worked to establish water supply to L-5. Engine 3 arrived on scene at approximately 1940 hours and also worked to get a water supply established to L-5. Water supply was established at approximately 1944 hours.

Engine 16

At the time of the incident, Engine 16 (E-16) was designated as the 3rd due engine on all confirmed structure fires in the department’s western district if not assigned on the initial dispatch. Note: NIOSH investigators were told that the 3rd due engine is designated as the “Safety Team” and should have been held on stand-by at the scene. However, the crew was instructed to engage in fire suppression activities before they arrived on-scene.

The crew was in quarters when the fire dispatch was initiated. The E-16 crew consisted of a captain (Victim # 5), an engineer, and a fire fighter (Victim # 3). E-16 started to move toward the scene when BC-4 reported smoke in the area. At approximately 1915 hours, the AC radioed E-16 to bring a 2 ½” hose line in the front door. E-16 arrived on scene driving west to east. The E-16 captain and fire fighter dismounted the engine and went to talk to the AC. They took a 2 ½” hose line with a stacked-tip nozzle (uncharged) into the main showroom and advanced it to the double doors leading to the loading dock and met up with the acting captain from E-11. This was the last confirmed location of the E-16 crew.

The E-16 engineer was instructed to lay a supply line for E-11 so he drove east on the highway toward where a hydrant had been previously located. This hydrant had been removed in 2004 because it had received damage from heavy truck traffic in the immediate area. He continued east to the next hydrant located approximately 1,200 feet away. Note: 1,850 feet of a single 2 ½” supply line was stretched from E-11 to the hydrant. The E-16 engineer reported hearing the radio traffic about the civilian worker being trapped in the rear of the building just as he was pulling up to the hydrant. (see Diagram # 2)

At approximately 1919 hours, the E-16 captain radioed to charge the 2 ½” hoseline (inside the building). The E-11 engineer radioed the E-11 acting captain to ask if he wanted the 2 ½” hoseline charged. The AC responded to not charge the 2 ½” hoseline until the supply line from E-16 to E-11 was charged. Note: Water supply from E-16 to E-11 was not yet established at this point. Water supply from E-16 to E-11 was established at approximately 1926 hours. After the hose was stretched out, traffic on the highway began to drive over the supply line from E-16 to E-11. The E-16 engineer radioed dispatch that the city police were needed for traffic control. As crews attempted to battle the escalating fire, water supply became an issue. Later, during the time period from 1937 hours to 1941 hours, chief officers in front of the showroom repeatedly called the E-16 engineer to boost water pressure to E-11 as the fire escalated out of control. At approximately 1941 hours, the E-16 engineer was instructed to switch to another radio channel to clear up the main channel for rescue purposes.

Engine 12

The Engine 12 (E-12) crew, consisting of an acting captain, assistant engineer, and two fire fighters were in quarters at the time of the initial dispatch. At approximately 1912 hours, the AC radioed dispatch to send E-12 to the scene. While enroute, BC-4 radioed E-12 and instructed them to lay a supply line down the alley on the D-side of the building to E-10. Engine 12 acknowledged this assignment. The Fire Chief also radioed the same instructions.

Engine 12 arrived on-scene at approximately 1917 hours and hooked up a 2 ½” supply line to E-10, then drove across the highway and down a side street to a hydrant, laying out 15 sections of supply line. The E-12 engineer hooked up to the hydrant and operated the pumps supplying E-10 throughout the incident. Water supply to E-10 was established at approximately 1920 hours. The E-12 acting captain and fire fighters assisted the E-10 crew by repairing the 1 ½” hoseline that had burst, then forced open the walk-thru door at the front of the warehouse and advanced a 2 ½” hoseline inside the warehouse about 10 feet before being ordered to withdraw. The 2 ½” hoseline was then operated through the doorway into the warehouse. The fire was reported to be burning so hot that the water immediately turned to steam and did little good in suppressing the fire.

Note: The E-12 crew reported that while forcing open the warehouse door, they experienced problems with a gasoline powered saw that had the wrong type of blade (for cutting plywood, not metal). Crews had to use axes to cut through the metal siding. The E-12 crew also cut holes in the metal siding along the D-side walls for ventilation and to direct water streams inside the building (see Photo 10).

Later in the incident, additional supply lines were stretched to E-12 so that E-12 could pump to E-11 and L-5 and L-4. Chief Officers radioed E-12 to boost the water pressure to E-10 at least 3 times during the incident. The E-12 engineer also radioed dispatch to have the city police department stop traffic on the highway from running over the supply lines.

Engine 15

The Engine 15 crew was in quarters when the first alarm crews were dispatched. The E-15 crew consisted of a captain (Victim # 8), engineer, and two fire fighters. One of the E-15 fire fighters ( fire fighter # 2) was newly hired and was responding to his first working structure fire with the department. Per department procedures, E-15 began to relocate from downtown to the west side. The E-15 crew reported that smoke was visible from a couple of miles away as they relocated so they began running hot (Code 3 – lights and sirens on). At approximately 1912 hours, the Fire Chief radioed dispatch to have Engine 15 relocate to Station 11. Almost immediately, the AC radioed for E-15 to come to the scene. Then the AC radioed E-15 to bring a 1 ½” hose line to the right rear of the building.

Engine 15 arrived on-scene at approximately 1917 hours just as Engine 16 began dropping a supply line for Engine 11. The E-15 captain instructed the E-15 engineer to get dressed to go inside the building. Note: During the NIOSH interviews, numerous fire fighters reported that most fire fighters responding after the first alarm would be expected to enter a structure fire for additional interior support. Coordinated ventilation and ladder truck operations reportedly were seldom initiated.

The E-15 captain and two fire fighters donned their SCBA and proceeded to Engine 11. One fire fighter took a pike pole and Haligan bar while the other fire fighter took an axe. They briefly talked with the E-11 engineer. They observed two hose lines going through the front entrance and followed the hose lines (one 1 ½” and one 2 ½”) inside. Visibility at the front of showroom was still good at this time and the crew did not go on air until they were about 10 feet inside the door. As the E-15 crew advanced further, the visibility decreased. They were aware of other crews working to their right. The E-15 captain discussed with his crew that he wanted to work a hose line to the center and left rear of the main showroom to cut the fire off from spreading in that direction (contain fire to the right rear corner). The E-15 captain instructed fire fighter # 2 to go outside and get a hose line.

Fire fighter # 2 went outside and pulled a booster line (1” red hose) as far as he could down the center walkway through the main showroom. By this point, the visibility had decreased to where it was difficult to distinguish other fire fighters moving nearby. Fire fighter # 2 moved as far as he could and then began to flow water from the booster line toward a red glow overhead. He ran low on air and followed the hoseline toward the front entrance. Once outside he changed his air cylinder, then followed the hoseline back inside. He heard airhorns sounding (evacuation signal)and followed the hoseline back outside.

The E15 engineer donned his PPE and went to the front door where he assisted fire fighter # 2 in pulling the booster line through the front door. The E15 engineer advanced inside the showroom about 10 feet where he encountered thick black smoke from ceiling to floor. He could see a red glow at the rear of the showroom but no distinct flames. He ran low on air and went outside and changed his SCBA cylinder then re-entered the main showroom. It was noticeably hotter inside the showroom as the E15 engineer entered the second time. The engineer heard three airhorn blasts then heard radio traffic about evacuating the building so he followed the hose line outside.