Fire Fighter Suffers Sudden Cardiac Death During Fire Fighting Operations – California

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2006-03 Date Released: May 31, 2006

SUMMARY

On November 5, 2005, a 43-year-old male career Fire Fighter (FF) was engaged in exterior fire fighting operations at a residential structure fire. After fire extinguishment and debriefing, he walked to his engine to retrieve his turnout gear and suddenly collapsed. A nearby crew member witnessed the FF collapse and alerted other crew members. Dispatch was notified and sent an ambulance. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was performed, advanced life support (ALS) treatment was given, and the FF was transported to the local hospital’s emergency department (ED). Despite CPR and ALS treatment, the FF died. The death certificate and the autopsy listed “atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD)” as the cause of death. The NIOSH investigator concluded that the FF’s sudden cardiac death was due to his underlying atherosclerotic CVD, possibly triggered by the physical exertion associated with fire fighting duties.

NIOSH investigators offer the following recommendations to prevent similar incidents, and to address general safety and health issues:

- Provide annual medical evaluations consistent with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1582 to ALL fire fighters to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

- Phase in a MANDATORY wellness/fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

- Perform an annual physical performance (physical ability) evaluation to ensure fire fighters are physically capable of performing the essential job tasks of structural firefighting.

- Institute incident scene rehabilitation (rehab) during working structural fires.

- Provide a transport ambulance at the scene of working structural fires.

- Discontinue lumbar spine x-rays as a screening test administered during the pre-placement medical evaluation.

INTRODUCTION & METHODS

On November 5, 2005, a 43-year-old male FF suffered sudden cardiac death after performing fire extinguishment duties at a residential structure fire. NIOSH was notified of this fatality on November 7, 2005, by the United States Fire Administration. NIOSH contacted the affected fire department (FD) on November 28, 2005, to obtain further information, and on January 20, 2006, to initiate the investigation. On February 13, 2006, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Team traveled to California to conduct an on-site investigation of the incident.

During the investigation, NIOSH personnel interviewed the following persons:

- Fire Chief

- Division Chief for Training

- Deputy Chief for Operations

- Arson Investigator

- Crew members

- FF’s wife and sister

NIOSH personnel reviewed the following documents:

- FD incident report

- FD training records

- FD annual response report for 2005

- FD standard operating guidelines

- Ambulance report

- Hospital records

- Death certificate

- Autopsy report

- Primary care provider (PCP) records

INVESTIGATIVE RESULTS

On November 5, 2005, the FF (assigned to Engine 8[E-8]) arrived for duty at his fire station (Station 8) at about 0700 hours. Throughout the day, the FF got his bunker gear ready, performed housecleaning, and mowed the fire station lawn.

At 1611 hours, E-8, E-7, and Battalion 2 (a total of nine personnel) were dispatched to a vegetation fire. As Dispatch received additional information the call was upgraded to a “vacant residence on fire.” At 1613 hours, Truck 2, Truck 1, and Squad 2 (a total of nine additional personnel) were also dispatched. E-8 arrived on scene at 1616 hours; others began to arrive four minutes later. A total of 29 personnel eventually responded.

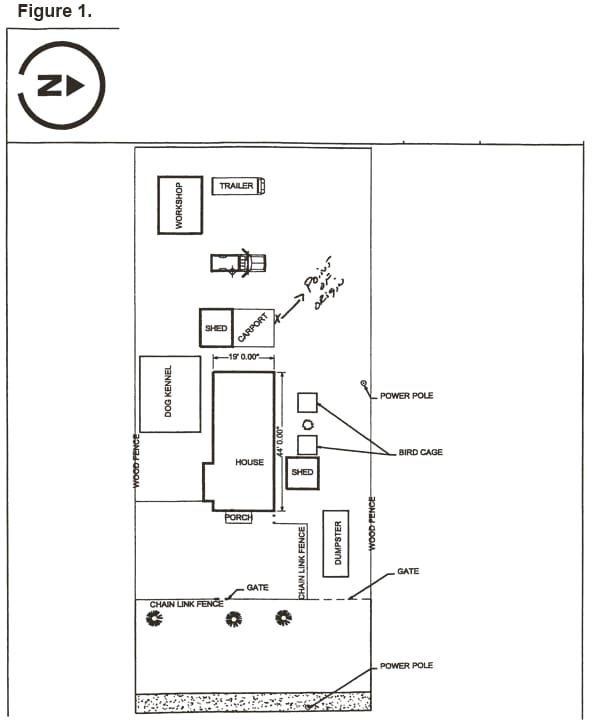

Arriving units found a vacant residence fully involved in fire. The single-story wood frame structure measured 44-feet by 19-feet; it was situated on a fenced-in lot that was overgrown with excessive vegetation and contained a large amount of clutter in the yard. There was an unattached shed and carport (the fire’s point of origin). (See Figure 1). The FF pulled the load of 2½-inch hose and a 2½-inch gated wye and stretched out the hose. He and a crew member then pulled 100 feet of 1½-inch handline each and carried them to the structure. The FF, wearing full turnout gear and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), not on air, began fire extinguishment from outside the structure (defensive operation) at 1623 hours.

The FF started on the side of the structure and continued around to the front. Smoke and steam production increased as the fire was extinguished. At 1626 hours, the fire was declared under control but not out. The E-8 Captain told the FF to assist other crew members in removing a door and boards off the front windows. The FF told the Captain that he had been exposed to a “pretty big hit of smoke” at some point. The Captain asked the FF if he was okay, to which the FF replied “yes.” The FF walked to E-8, removed his SCBA and turnout coat, climbed into the cab to rest, and rehydrated with water. The Engineer of E-8 asked the FF if he was okay. The FF told the Engineer that he had taken a “big whiff of smoke” and just needed a couple of minutes to recover. The Engineer did not see any signs of distress or any problems with the FF.

After resting approximately 10 minutes, the FF donned his turnout gear and SCBA and joined crew members performing fire suppression. A few minutes later, a “Fire Buffs” truck (volunteer group) arrived with water and snacks. The FF walked to E-8, removed his turnout coat and SCBA, and re-entered the cab of E-8. The Engineer asked the FF again if he was okay; to which the FF replied that he was. A decision was made to fight the fire with the ladder truck’s deluge gun, which lasted for about 10 minutes but did not seem to be successful in controlling the fire. This action caused smoke production to greatly increase.

The E-8 Captain called the crew together for a briefing at the rear of E-8. The FF attended the briefing in which the Captain advised the crew that they would have to enter the structure to effect final extinguishment. Since the structure did not have a floor, extra safety precaution was advised. The FF went to the other side of E-8 to obtain his turnout gear and SCBA. As the FF obtained his gear, he suddenly collapsed backward onto the ground. The Engineer, who was standing beside the FF, advised the Captain of the situation. The Captain notified Dispatch, who sent an ambulance at 1753 hours.

Crew members assessed the FF and found him to be unresponsive, without a pulse, and not breathing; CPR was begun. An oralpharyngeal airway was inserted and oxygen was administered via bag-valve-mask. Proper tube placement was confirmed by an end tidal carbon dioxide test. A cardiac monitor was attached to the FF, revealing ventricular fibrillation (Vfib.) (a heart rhythm incompatible with life). Three shocks (defibrillation attempts) were delivered without a change in his heart rhythm. An intravenous line was started and cardiac resuscitation medications were administered.

The ambulance arrived at 1802 hours and the FF was re-assessed. Finding no pulse and respirations, CPR and ALS were continued. The FF was placed onto a stretcher and into the ambulance, which departed the scene bound for the hospital at 1805 hours. En route, the FF’s heart rhythm was analyzed again, found to be in Vfib., and three additional shocks were delivered, with no change in cardiac rhythm.

The ambulance arrived at the hospital ED at 1811 hours; about 18 minutes after his collapse. Initial evaluation in the ED found the FF to be unresponsive, with CPR in progress, and asystole (no heart beat) on the cardiac monitor. ALS measures continued and at approximately 1825 hours, a heart rhythm with a pulse returned. At 1833 hours, his heart rhythm converted to wide complex tachycardia at a rate about 170 beats per minute. An electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed “hyperacute ST segment elevation; highly suggestive of an acute myocardial infarction.” Blood testing to confirm a heart attack (troponin) was done which revealed a Troponin I level of 0.04 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), representing an intermediate level (0.04 – 0.5 ng/mL). His blood carboxyhemoglobin level about 70 minutes post exposure was 0.005% (normal is 0.005 % to 0.015 %) indicating the FF was not exposed to significant amounts of carbon monoxide.

The FF was taken for a CT scan at 1842 hours. As the scan began, his heart rhythm reverted to Vfib. CPR was initiated and he was shocked again; his heart rhythm converting to pulseless electrical activity. Additional cardiac resuscitation medications were administered. The CT scan did not reveal any intracranial bleeding and thrombolytic therapy was administered (i.e. intravenous medication used to break up blood clots). Throughout the next 28 minutes, the FF was shocked four additional times with no change in his clinical course. The FF was pronounced dead by the attending physician at 1910 hours and resuscitation measures were discontinued.

Medical Findings. The death certificate (completed by the County Coroner) and the autopsy (completed by the Chief Forensic Pathologist in the Coroner’s Office) listed “atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD)” as the cause of death. Pertinent findings from the autopsy, performed on November 7, 2005, included the following:

- Atherosclerotic CVD

- o Complete narrowing (100%) of the right coronary artery

- Severe narrowing (75%) of the left main coronary artery

- Severe narrowing (75%) of the left anterior descending coronary artery

- No evidence of an intra-coronary blood clot (thrombus), but thrombolytic medications were given in the ED

- Enlarged heart (cardiomegaly): heart weighed 450 grams (g) (normal is <400 g)1

- Dilatation of the heart

- Slight thickening of the left ventricle (wall thickness is 1.5 centimeters [cm]) (normal is 0.6 cm – 1.1 cm)2

- No evidence of a pre-mortem pulmonary thromboemboli (i.e., blood clots in the lungs)

- Negative carboxyhemoglobin test

- Negative drug and alcohol tests

Microscopic examination results from the autopsy were not available at the time of this report.

The FF had no known history of coronary artery disease (CAD) but did have two CAD risk factors: hypertension (HTN) and obesity. At the time of his death, the FF was 70 inches tall and weighed 222 pounds, giving him a body mass index (BMI) of 31.8 kilograms per square meter (kg/m2).3 A BMI of 30.0 to 39.9 is considered obese.3

In 2004, the FF had a few episodes of slightly elevated blood pressure, but was not prescribed blood pressure-lowering medication. A blood lipid test revealed elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels, but the FF was not prescribed lipid-lowering medication. In January 2005, the FF was hospitalized for an episode of altered level of consciousness, memory loss, and headache. After a battery of tests including electrocardiograms (EKGs), a computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain, chest x-ray, and various blood tests (including cardiac isoenzymes) were non-diagnostic, and a presumptive diagnosis of amnesia and viral encephalitis was made. According to the FF’s wife and crew members, he did not express any symptoms of cardiac-related problems during the days or months prior to his death.

DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT

At the time of the NIOSH investigation, this career FD consisted of 202 uniformed personnel, served a population of 300,000 in an 87 square-mile area, and had 13 fire stations.

In 2005, the FD responded to 27,083 calls: 240 structure fires, 209 vegetation fires, 245 vehicle fires, 328 refuse/rubbish fires, 72 other fires, 15,042 rescue and emergency medical calls, 871 hazardous condition calls, 1,786 service calls, 6,875 good intent calls, 1,171 false calls, and 244 other calls.

Employment and Training. The FD requires all fire fighter applicants to complete an application; possess a valid state driver’s license; possess a high school diploma or equivalent; complete a state fire academy (one year full-time paid fire fighter experience with a municipal FD may substitute); possess a certificate for passing a state-certified physical ability test within the previous six months; possess a current American Heart Association CPR card; possess a valid state emergency medical technician (EMT)-1 certification; and pass a written test, an oral interview, and a background investigation prior to being ranked. When called for a job opening, the candidate must pass a pre-placement physical examination prior to being offered employment. Fire fighters work 24 hours on duty 0730 hours to 0730 hours, are off duty for 24 hours, for four shifts, then are off duty for four days. The 24-hour on duty/24-hour off duty cycle is repeated for four additional shifts, then the fire fighter is off duty for six days.

The FF was certified as a Fire Fighter 1, EMT 1-D (defibrillator), and in Hazardous Materials Operations. He had 17 years of fire fighting experience.

Pre-placement Physical Examination. A pre-placement physical examination is required by this FD for all candidates. The contents of the examination are as follows:

- Complete medical history

- Physical examination

- Vital signs

- Complete blood count

- Complete metabolic panel

- Vision screening

- Audiogram

- Urinalysis

- Spirometry

- Respirator clearance

- Resting EKG

- Chest x-ray

- Lumbar spine x-ray

- Tuberculin PPD (purified protein derivative)

- Hepatitis A vaccine

City-contracted physician performs the medical examinations and forwards the clearance-for-duty decision through the City Human Resources office to the FD, who makes the final determination for clearance for duty.

Periodic Evaluations. Annual FD medical evaluations are required for all fire fighters. The contents of the examination differ for fire fighters, hazardous materials team members, and Urban Search and Rescue team members. The evaluation for fire fighters includes hearing test, TB skin test, pulmonary function test, and respirator medical evaluation. Medical clearance for SCBA use is required for all fire fighters annually. The same City-contracted physician performs these periodic medical evaluations and forwards the clearance-for-duty decision through the City Human Resources Office to the FD, who makes the final determination for clearance for duty.

No annual physical agility test is required. There is a voluntary wellness/fitness program that allows a fire fighter to use on-duty time for physical exercise. Exercise equipment (strength and aerobic) is available in all the fire stations. The FD has a contract with a local community college to perform fitness testing which includes a stress EKG, aerobic and anaerobic tests, a written report, and a prescribed fitness program for each fire fighter who participates. The City has an annual health fair and a weight watcher’s program that fire fighters may participate in. For non-duty-related illnesses or injuries, firefighters must submit to their supervisor a statement of disability from a treating physician stating that the fire fighter’s condition prevented them from performing their duties, if they missed one and a half consecutive shifts (36 hours) or more. The clearance is provided through the City Human Resources Office to the FD, who reviews it and makes a final determination regarding return to work.

DISCUSSION

CAD and the Pathophysiology of Sudden Cardiac Death. In the United States, CAD (atherosclerosis) is the most common risk factor for cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.4 Risk factors for its development include increasing age, male gender, heredity, tobacco smoking, diabetes, high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, and physical inactivity/obesity.5 The FF had three known risk factors for CAD: male gender, high blood pressure, and obesity. According to witnesses, the FF did not report symptoms of angina (e.g., chest pain on exertion) prior to his collapse. He only mentioned that he had inhaled smoke from the structure fire and needed a chance “to rehab.”

The narrowing of the coronary arteries by atherosclerotic plaques occurs over many years, typically decades.6 However, the growth of these plaques probably occurs in a nonlinear, often abrupt fashion.7 Heart attacks typically occur with the sudden development of complete blockage (occlusion) in one or more coronary arteries that have not developed a collateral blood supply.8 This sudden blockage is primarily due to blood clots (thrombosis) forming on the top of atherosclerotic plaques. Blood clots, or thrombus formation, in coronary arteries is initiated by disruption of atherosclerotic plaques. Certain characteristics of the plaques (size, composition of the cap and core, presence of a local inflammatory process) predispose the plaque to disruption.8 Disruption then occurs from biomechanical and hemodynamic forces, such as increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, increased catecholamines, and shear forces, which occur during heavy exercise.9

Establishing the occurrence of a heart attack requires any of the following: coronary artery thrombus, characteristic EKG changes, or elevated cardiac enzymes. Although no thrombus was present at autopsy, the FF had thrombolytic medications administered in the ED. His EKG in the ED had changes consistent with a heart attack (elevated ST segments). His cardiac isoenzyme Troponin I was only slightly elevated, but given that he died less than two hours after his collapse, this is not inconsistent with a heart attack (Troponin I levels are detectable 3 – 6 hours after myocardial damage and peak at approximately 12 – 16 hours, and can remain elevated for 4 – 9 days.10 Therefore, the NIOSH investigator believes that the FF had an acute MI resulting in his sudden cardiac death. However, a primary cardiac arrhythmia associated with his slight left ventricular hypertrophy cannot be ruled out.

Fire fighting is widely acknowledged to be one of the most physically demanding and hazardous of all civilian occupations.11 Fire fighting activities are strenuous and often require fire fighters to work at near maximal heart rates for long periods. The increase in heart rate has been shown to begin with responding to the initial alarm and persist through the course of fire suppression activities.12-14 Even when energy costs are moderate (as measured by oxygen consumption) and work is performed in a thermoneutral environment, heart rates may be high (over 170 beats per minute), owing to the insulative properties of the personal protective clothing.15 Epidemiologic studies have found that heavy physical exertion sometimes immediately precedes and triggers the onset of acute heart attacks.16-19 The FF, while wearing turnout gear and SCBA, pulled the load of 2½-inch hose and 2½-inch gated wye and stretched out the hose. He then pulled 100 feet of 1½-inch handline and carried it to the structure. The FF then began exterior fire extinguishment. The FF also assisted other crew members in removing a door and boards off the front windows. This is considered a very heavy level of physical exertion.11,20 The physical stress of performing these tasks, and his underlying atherosclerotic CAD, contributed to this fire fighter’s sudden cardiac death.

Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH). On autopsy, the FF had an enlarged heart and slight LVH. LVH is a relatively common finding among individuals with long-standing HTN, a heart valve problem, or cardiac ischemia (reduced blood supply to the heart muscle).1 The FF had no signs of cardiac ischemia, but did have a history of mild HTN. LVH increases the risk for sudden cardiac death.1

Occupational Medical Standards for Structural Fire Fighters. To reduce the risk of sudden cardiac arrest or other incapacitating medical conditions among fire fighters, the NFPA developed NFPA 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments.21 NFPA 1582 recommends, for informational purposes only, asymptomatic fire fighters with two or more risk factors for CAD be screened for obstructive CAD by an exercise stress test (EST). NFPA defines these CAD risk factors as: family history of premature (first-degree relative <age 60) cardiac event, hypertension (diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg), diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, and hypercholesterolemia (total blood cholesterol level >240 mg/dL).21 This guidance is similar to recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the Department of Transportation regarding ESTs in asymptomatic individuals.22,23 Since the FF had one known NFPA CAD risk factor (hypertension), an EST would not have been recommended by NFPA 1582, the ACC/AHA, or the DOT.21-23

RECOMMENDATIONS

NIOSH investigators offer the following recommendations to prevent similar incidents and to address general safety and health issues:

Recommendation #1: Provide annual medical evaluations consistent with NFPA 1582 to ALL fire fighters to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

Guidance regarding the content and frequency of periodic medical evaluations and examinations for structural fire fighters can be found in NFPA 158221 and in the report of the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFF/IAFC) wellness/fitness initiative.24 These medical examinations recommend an annual auscultation of the heart, resting EKG, and EST for fire fighters with two or more risk factors for CAD. It should be noted the FD is not legally required to follow these standards.

The medical evaluation mentioned above could be conducted by the fire fighter’s PCP or a City-contracted physician. If the evaluation is performed by the fire fighter’s PCP, the results must be communicated to the City physician, who makes the final determination for clearance for duty.

Applying NFPA 1582 involves economic issues. These economic concerns go beyond the costs of administering the medical program; they involve the personal and economic costs of dealing with the medical evaluation results. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, Chapters 8-7.1 and 8-7.2 address these issues.25

Recommendation #2: Phase in a MANDATORY wellness/fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for CVD and improve cardiovascular capacity.

Physical inactivity is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for CAD in the United States. NFPA 1500 requires a wellness program that provides health promotion activities for preventing health problems and enhancing overall well-being.25 NFPA 1583, Standard on Health-Related Fitness Programs for Fire Fighters, provides the minimum requirements for a health-related fitness program.26 In 1997, the IAFF/IAFC published a comprehensive Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative to improve fire fighter quality of life and maintain physical and mental capabilities of fire fighters. Ten FDs across the United States joined this effort to pool information about their physical fitness programs and create a practical fire service program. They produced a manual and a video which details elements of such a program.24 Large-city negotiated programs can also be reviewed as potential models. Wellness programs have been shown to be cost effective, typically by reducing the number of work-related injuries and lost work days.27-29 Similar cost savings have been reported by the wellness program at the Phoenix FD, where a 12-year commitment has resulted in a significant reduction in their disability pension costs.30

Recommendation #3: Perform an annual physical performance (physical ability) evaluation to ensure fire fighters are physically capable of performing the essential job tasks of structural firefighting.

NFPA 1500 requires FD members who engage in emergency operations to be annually evaluated and certified by the FD as having met the physical performance requirements identified in paragraph 8-2.1.25

Recommendation #4: Institute incident scene rehabilitation (rehab) during working structural fires.

The incident commander should consider the circumstances of each incident and initiate rest and rehabilitation.25 Members performing intense work for 20 minutes without SCBA should receive at least 10 minutes of self-rehab.31 A location for rehab should be sufficiently far away from the effects of the operation that members can safely remove their personal protective equipment and SCBA.31 On-scene rehab should be staffed, include at least basic life support, and have fluid and food available.31 Members entering rehab should receive medical monitoring including rating of perceived exertion, heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature.31 While the fire at this incident was considered a routine residential fire to be fought defensively, fire fighters still performed heavy physical exertion while effecting fire suppression activities. A volunteer group responded to the scene with fluids for rehab, but no designated area for rehab had been identified nor procedures for medical monitoring.

Recommendation #5: Provide a transport ambulance at the scene of working structural fires.

The incident commander should evaluate the risk to members operating at emergency scenes and request that at least basic life support personnel and patient transportation be available.25 This fire was primarily a defensive operation. Advanced Life Support was on the scene and the crew members did an outstanding job in patient care; however a patient transport vehicle was not a part of the emergency response. A transport ambulance dispatched to confirmed working fires or special operations would ensure rapid transportation to a hospital in the event of fire fighter injury.

Recommendation #6: Discontinue lumbar spine x-rays as a screening test administered during the pre-placement medical evaluation.

The FD currently performs pre-placement physical evaluations, which include routine lumbar spine X-rays. While these X-rays may be useful in evaluating individuals with existing problems, the American College of Radiology, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and NIOSH have concluded that lumbar spine X-rays have no value as a routine screening measure to determine risk for back injuries.32-34 This procedure involves both an unnecessary radiation exposure for the applicant and an unnecessary expense for the FD.

REFERENCES

- Siegel RJ [1997]. Myocardial hypertrophy. In: S. Bloom (ed). Diagnostic criteria for cardiovascular pathology acquired diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippencott-Raven, pp. 55-57.

- Armstrong WF, Feigenbaum H [2001]. Echocardiography. In: Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Heart disease: a text of cardiovascular medicine. 6th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company, p. 167.

- National Heart Lung Blood Institute [2006]. Obesity education initiative [online]. World Wide Web (Date accessed: January 2006.) Available from URL: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/BMI/bmicalc.htmexternal icon. (Link Updated 1/16/2013)

- Meyerburg RJ, Castellanos A [2001]. Cardiovascular collapse, cardiac arrest, and sudden cardiac death. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 228-233.

- AHA [1998]. AHA scientific position, risk factors for coronary artery disease. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association.

- Libby P [2001]. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. p.1378.

- Shah PK [1997]. Plaque disruption and coronary thrombosis: new insight into pathogenesis and prevention. Clin Cardiol 20 (11 Suppl2): II-38-44.

- Fuster V, Badimon JJ, Badimon JH [1992]. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. N Eng J Med 326:242-250.

- Kondo NI, Muller JE [1995]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Risk 2:499-504.

- Newby LK, Christenson RH, Ohman EM, et al. [1998]. Value of serial troponin T measures for early and late risk stratification in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 98:1853-1859.

- Gledhill N, Jamnik VK [1992]. Characterization of the physical demands of firefighting. Can J Spt Sci 17(3):207-213.

- Barnard RJ, Duncan HW [1975]. Heart rate and ECG responses of fire fighters. J Occup Med 17:247-250.

- Manning JE, Griggs TR [1983]. Heart rate in fire fighters using light and heavy breathing equipment: simulated near maximal exertion in response to multiple work load conditions. J Occup Med 25:215-218.

- Lemon PW, Hermiston RT [1977]. The human energy cost of fire fighting. J Occup Med 19:558-562.

- Smith DL, Petruzzello SJ, Kramer JM, et al. [1995]. Selected physiological and psychobiological responses to physical activity in different configurations of firefighting gear. Ergonomics 38(10):2065-2077.

- Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, et al. [1993]. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med 329:1684-1690.

- Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, et al. [1993]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. N Eng J Med 329:1677-1683.

- Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T [1984]. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Eng J Med 311:874-877.

- Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, et al. [1992]. Modifiers of timing and possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Phase II (TIMI II) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:1049-1055.

- American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal [1971]. Ergonomics guide to assessment of metabolic and cardiac costs of physical work. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 560-564.

- NFPA [2003]. NFPA 1582: Standard on comprehensive occupational medical program for fire departments. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [2002]. Guideline update for exercise testing: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, et al., eds. [online] American College of Cardiology website. Available from URL: http://content.onlinejacc.org/data/journals/JAC/22975/21642.pdfpdf iconexternal icon. Accessed March 2006. (Link Updated 10/28/2013)

- U.S. Department of Transportation [2002]. Cardiovascular advisory panel guidelines for the medical examination of commercial motor vehicle drivers. Washington, DC: DOT; FMCSA, Publication No. FMCSA-MCP-02-002. [online] Accessed June 2005. Available from URL: http://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/docs/cardio.pdfpdf iconexternal icon (Link Updated 5/13/2015) .

- IAFF, IAFC. [2000]. The fire service joint labor management wellness/fitness initiative. Washington, D.C.: International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs.

- NFPA [2002]. NFPA 1500: Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2000]. NFPA 1583: Standard on health-related fitness programs for fire fighters. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Maniscalco P, Lane R, Welke M, Mitchell J, Husting L [1999]. Decreased rate of back injuries through a wellness program for offshore petroleum employees. J Occup Environ Med 41:813-820.

- Stein AD, Shakour SK, Zuidema RA [2000]. Financial incentives, participation in employer sponsored health promotion, and changes in employee health and productivity: HealthPlus health quotient program. JOEM 42:1148-1155.

- Aldana SG [2001]. Financial impact of health promotion programs: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 15:296-320.

- Unpublished data [1997]. City Auditor, City of Phoenix, AZ. Disability retirement program evaluation. January 28, 1997.

- NFPA [2003]. NFPA 1584: Recommended practice on the rehabilitation of members operating at incident scene operations and training exercises. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Gibson ES [1998]. The value of pre-placement screening radiography of the low back. In: Deyo RA, ed. Occupational medicine, state of the art reviews. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, pp. 91-108.

- Present AJ [1974]. Radiography of the Lower Back in Pre-employment Physical Examinations. Conclusions of the ACR/NIOSH Conference, January 11-14, 1973. Radiology 112:229-230.

- Lincoln TA, Kelly FJ, Lushbaugh CC, Milroy WC, Voelz GL, Wollenweber HL [1979]. Guidelines for use of routine x-ray examinations in occupational medicine. Committee report. J Occ Med Jul;21(7)500-502.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by and the report written by:

Tommy N. Baldwin, MS, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist

Mr. Baldwin, a National Association of Fire Investigators (NAFI) Certified Fire and Explosion Investigator, an International Fire Service Accreditation Congress (IFSAC) Certified Fire Officer I, and a Kentucky Certified Fire Fighter and Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), is with the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Cardiovascular Disease Component located in Cincinnati, Ohio.

This page was last updated on 07/10/06.