Fire Fighter Suffers Sudden Cardiac Death While Performing Work Capacity Test – California

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2004-28 Date Released: June 3, 2005

SUMMARY

On May 31, 2002, a 59-year-old male career Fire Fighter (FF) was scheduled for a “Pack Test.” The Pack Test is one of three work capacity tests (WCT) designed to simulate the physical demands of wildland fire fighting. The Pack Test requires an individual to complete a 3-mile walk within 45 minutes while wearing a 45-pound vest. Successful completion of the Pack Test within the 45 minutes allows fire fighters to participate in federal wildland fire fighting operations. The FF began the Pack Test at approximately 0910 hours and had completed about 1.3 miles of the test when he suddenly collapsed. Crew members (emergency medical technicians [EMTs]) witnessed the collapse and initial assessment found the FF unresponsive with no pulse or respirations. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was begun. On-scene ambulance paramedics quickly began advanced life support (ALS) measures. Despite these measures by crew members, ambulance paramedics, air ambulance paramedics, and hospital emergency department (ED) personnel, the FF died. The death certificate and autopsy, completed and performed by the County Chief Deputy Medical Examiner, listed “coronary atherosclerosis” as the immediate cause of death. The Medical Examiner further stated, “the death is attributed to a sudden cardiac arrhythmia during physical exertion as a result of myocardial ischemia due to longstanding coronary atherosclerosis.” The NIOSH investigator agrees with this conclusion. Additionally, the screening mechanism for coronary artery disease (CAD) is inadequate.

Recommendations 1–2 below address safety issues unique to this event. Recommendations 3–5 are preventive measures often recommended by fire service groups to reduce the risk of on-the-job heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters. These recommendations should be implemented by the Southern California Agency (SCA).

- Check WCT participants’ vital signs before testing.

- Modify the Health Screening Questionnaire (HSQ) in the Pacific Regional Handbook to include all cardiovascular risk factors identified by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC).

- Consider providing pre-placement and periodic medical evaluations to ALL fire fighters consistent with NFPA 1582 or equivalent to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

- Ensure that fire fighters are cleared for duty by a physician knowledgeable about the physical demands of fire fighting.

- Ensure that fire fighters participate in a mandatory wellness/fitness program designed for wildland fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

INTRODUCTION AND METHODS

On May 31, 2002, a 59-year-old male Fire Fighter walked 3 laps of a total of 7.5 laps around a track as part of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group/Bureau of Indian Affairs (NWCG/BIA) WCT when he suddenly collapsed. Despite CPR and ALS treatment at the scene, en route to the hospital, and in the ED, the FF died. NIOSH was notified of this fatality on June 10, 2002, by the United States Fire Administration. NIOSH contacted the affected Fire Department (FD) on June 21, 2002, to obtain further information. On September 13, 2004, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Team traveled to California to conduct an on-site investigation of the incident. During the investigation NIOSH personnel met and/or interviewed the following people:

- Fire Chief

- Natural Resources Officer from the BIA, Southern California Agency (SCA)

During the site visit NIOSH personnel reviewed the following documents:

- BIA/SCA policies and operating guidelines

- FD training records

- HSQ

- BIA/SCA incident report

- BIA/SCA physical examination protocols

- Air ambulance report

- Hospital ED records

- Death certificate

- Autopsy report

INVESTIGATIVE RESULTS

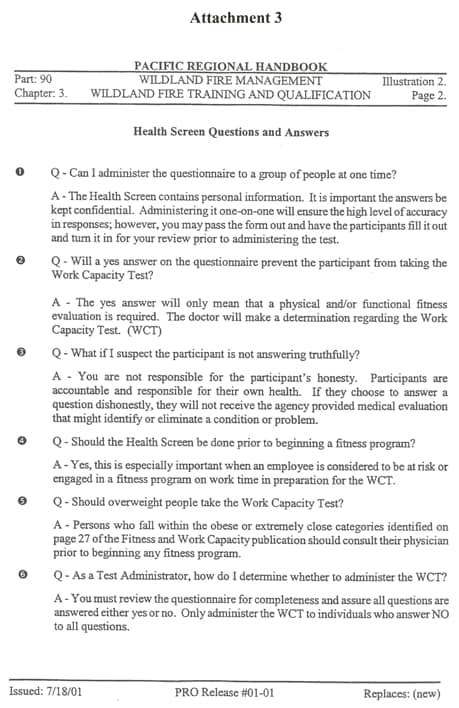

Incident. On May 31, 2002, the FF was scheduled to perform the Pack Test administered by the BIA/SCA. He arrived at the designated test location (parking lot located near his FD) at approximately 0900 hours. There were two test administrators and fifteen fire fighters taking the test. The test administrators had previously reviewed testing procedures including some “questions and answers” regarding the HSQ (Attachment 1). The track was tested with a pickup truck for proper distance. Seven and one-half laps around the track equaled 3 miles. EMTs and paramedics from the local FD were on-site, and water and other replacement fluids were available.

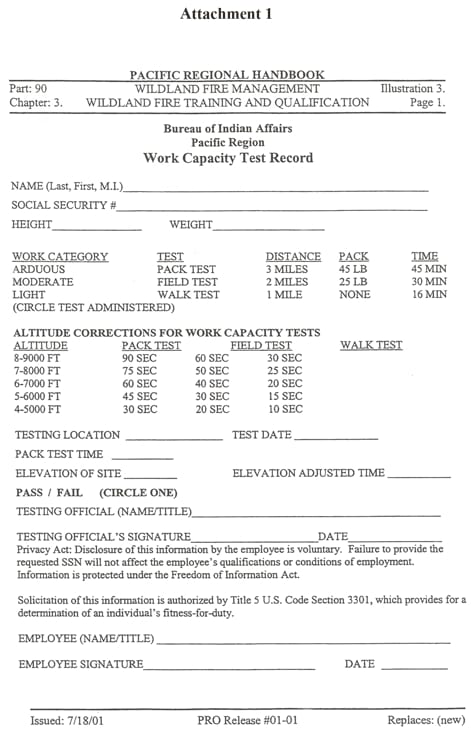

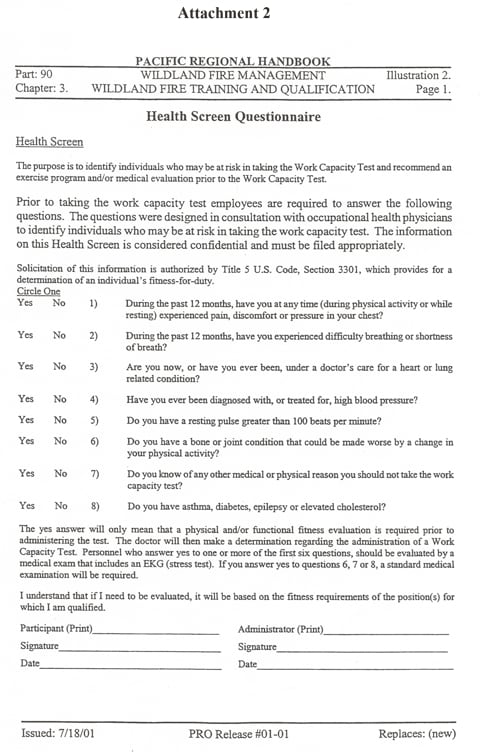

The Pack Test is the most arduous version of the WCT and involves walking a distance of 3 miles within 45 minutes while wearing a 45-pound vest. The FF was placed in Group One and was given a weighted vest. The two groups of participants were gathered together and briefed on the testing and safety procedures. Each participant completed the BIA Pacific Region WCT Record (Attachment 2), and the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q), otherwise known as the Health Screen Questionnaire (HSQ) (Attachment 3). The FF completed the WCT Test Record and the HSQ, answering “no” to all the health screening questions. A test administrator reviewed both forms before allowing the FF to participate. The temperature was in the low to mid 70° Fahrenheit range and by 0910 hours, Group One was ready to begin the test.

The FF completed the first lap in 6 minutes, 57 seconds, showing no symptoms of heart-related problems. He completed the second lap by 14 minutes and 6 seconds, and the third lap by 21 minutes and 29 seconds (0932 hours). He was offered water at the completion of each lap and took it each time. The group of nine participants had become dispersed along the track with the FF in the last position. He did not exhibit any heart-related symptoms or other sign of a problem. He had gone approximately 200 yards into his fourth lap (a total of about 1.3 miles), when he suddenly collapsed face down onto the asphalt pavement.

Participants immediately ran to aid the FF. They began a physical assessment, cut the WCT vest from him, and cleared his airway. Assessment revealed he was unresponsive, without pulse, and not breathing. CPR was begun as on-scene paramedics arrived and began ALS treatment including cardiac monitoring (asystole [no heart beat]), intubation (breathing tube inserted into the trachea), intravenous (IV) access, and cardiac resuscitation medications. At 0939 hours, an air ambulance was requested; it arrived on-scene at 0958 hours.

Initial assessment revealed an unresponsive patient with no heart beat (asystole), and with CPR and ALS in progress. At 1014 hours, the FF was placed into the air ambulance and transported, arriving at the local hospital at 1017 hours. Inside the ED, assessment revealed no change in patient status and the cardiac monitor continued to show asystole. The FF was pronounced dead at 1030 hours by the attending physician and resuscitation measures were stopped.

Medical Findings. The death certificate, completed by the Medical Examiner, listed “coronary atherosclerosis” as the immediate cause of death. The Medical Examiner further stated, “the death is attributed to a sudden cardiac arrhythmia during physical exertion as a result of myocardial ischemia due to longstanding coronary atherosclerosis.” Pertinent findings from the autopsy, also performed by the Medical Examiner on June 1, 2002, included:

- Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD)

Ischemic heart disease:- Near complete occlusion of the most proximal branch of the left anterior descending coronary artery

- 90% stenosis in the left circumflex coronary artery

- 70% stenosis in the right coronary artery

- No superimposed acute thromboses or recent hemorrhages

- Enlarged heart (cardiomegaly) weighing 510 grams (normal < 400 grams)1

- Mild to moderate perivascular fibrosis of the heart muscle on microscopic examination

- No evidence of a pulmonary embolus

- Vitreous (eye) chemistries showed elevations in sodium and chlorine consistent with dehydration

- Negative drug and alcohol tests

On autopsy, the FF weighed 214 pounds and was 69 inches tall, giving him a body mass index (BMI) of 31.7 kilograms per square meter (kg/m2). A BMI above 30.0 kg/m2 is considered obese.3 According to FD personnel, the FF participated in physical fitness training every shift and was encouraged to exercise off-duty. At his last periodic physical examination in July 1999, the FF weighed 210 pounds, and had a blood pressure of 144/82 millimeters of mercury (mmHg). Blood cholesterol levels were not checked. Unfortunately, the FF’s medical records from his primary care physician (PCP) could not be located.

During the last FD shift he worked prior to his collapse, the FF did not complain of any symptoms of angina (chest pain) or any other heart-related problems. According to medical records available to NIOSH, the FF was not prescribed any medications.

DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT

At the time of the NIOSH investigation, the Southern California Agency (SCA) managed a fire program to approximately 20 separate federal Indian reservations throughout Southern California. The SCA administers the WCT annually when a local fire department requests a test. Participants are classified as permanent employees, administrative hires, or temporary hires. The FF involved in this incident was classified as an on-call temporary hire federal emergency wildland fire fighter (EFF) with the BIA/SCA. He was also a permanent FF for his local FD (non-federal) and participated in structural fire fighting.

Training. All wildland fire fighter applicants over 45 years of age must pass a physical examination performed by the BIA’s medical contractor, complete the HSQ, and pass the WCT to perform duties while employed as a federal EFF in accordance with NWCG 310-1, Wildland and Prescribed Fire Qualification System Guide.4

The local FD where the FF was assigned full time requires all fire fighter candidates to complete an application, pass a criminal background check, a physical examination, and an oral interview prior to being selected. Once selected, the new candidate must pass a rigorous 2 week fire fighter academy that includes physical fitness, classroom, and practical training. Wildland fire fighters are required to run 5 miles, perform calisthenics for 1 hour, climb a 70° angle hill, and cut a fire line within 3 hours. Structural fire fighters perform physical fitness training on each shift, including 80 crunches, 30 pushups, 10 pullups, and running 3 miles within 30 minutes. Structural fire fighters’ shifts begin at 0800 hours, and they work 48 hours on duty, then have 96 hours off duty.

The FF was certified as a Fire Fighter II and a fire apparatus Driver/Operator. He had five years of fire fighting experience and had completed the WCT on three previous years.

Pre-placement/Pre-WCT Evaluations. The SCA requires a pre-placement medical evaluation for fire fighter candidates over 45 years of age. Components of the evaluation include:

- A complete medical history

- Physical examination

- Vital signs

- Vision screening

- Hearing test (conversation at 20 feet)

- Urinalysis

- Chest x-ray (if indicated)

- Resting electrocardiogram (EKG)

(if indicated)

These evaluations are performed by the BIA’s medical contractor. The fire fighter candidate provides the results to the WCT administrator, who then makes a decision regarding medical clearance to participate in the WCT.

Periodic Medical Evaluations. Annual medical evaluations are required by the SCA for all employees over 45 years of age. The evaluations are conducted by a BIA medical contractor, who determines the content of the evaluation and clearance for fire fighting duty.

Separate medical clearances for respirator use are not required for any of these three groups (permanent, temporary, or administratively determined employees).

If employees miss work due to an occupational or non-occupational illness or injury, they may have to be evaluated by their PCP. This PCP forwards any decision regarding work limitations to the employee’s supervisor, who makes the final decision whether these limitations can be accommodated by the SCA.

Fitness/Wellness Programs. Fitness/wellness and health maintenance programs are in place for permanent employees only. The SCA relies on the temporary FF’s local FD (their permanent employer) to provide fitness/wellness programs to temporary or administratively determined employees.

DISCUSSION

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) Risk Factors and the Pathophysiology of Sudden Cardiac Death. In the United States, CAD (atherosclerosis) is the most common risk factor for cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.5 Risk factors for its development include age over 45, male gender, family history of coronary artery disease, smoking, high blood pressure (systolic >140 millimeters of mercury [mmHg] or diastolic > 90 mmHg), high blood cholesterol (total cholesterol > 240 milligrams per deciliter [mg/dL]), obesity/physical inactivity, and diabetes.6,7 The FF had at least three of these risk factors (age over 45, male gender, obesity).

The narrowing of the coronary arteries by atherosclerotic plaques occurs over many years, typically decades.8 However, the growth of these plaques probably occurs in a nonlinear, often abrupt fashion.9 Heart attacks typically occur with the sudden development of complete blockage (occlusion) in one or more coronary artery that has not developed a collateral blood supply.10 This sudden blockage is primarily due to blood clots (thrombosis) forming on top of atherosclerotic plaques. Even though the FF did not have an intra-coronary blood clot, it is possible the FF suffered a heart attack; not all heart attacks have thromboses on autopsy. The more likely explanation for his sudden cardiac death is a heart arrhythmia. The FF had several conditions noted at autopsy that increase the risk of sudden death due to an arrhythmia. These include cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, and myocardial ischemia as evidenced by his severe atherosclerotic CAD.

Epidemiologic studies have found that heavy physical exertion sometimes immediately precedes and triggers the onset of acute heart attacks.11-14 The FF walked 1.3 miles within 21 minutes, 29 seconds. This is considered an unduly heavy level of physical exertion.15-17 The physical stress of walking briskly while wearing a 45-pound vest in combination with the underlying atherosclerotic CAD contributed to the FF’s sudden cardiac death.

Occupational Medical Standards for Structural Fire Fighters. The Pacific Regional Handbook requires a WCT Record, including a HSQ, be completed prior to a WCT. If a WCT applicant answers “yes” to any question, the applicant must receive a physical and/or functional fitness evaluation prior to taking the WCT.

National Fire Equipment System (NFES) 1596, Fitness and Work Capacity, provides information on fitness, work capacity, nutrition, hydration, the environment, work hardening, and injury prevention. It requires medical clearance for return to work, but not for pre-placement, periodic, or pre-WCT medical evaluations.17 NFES 1596 refers to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommendation for a medical examination for persons who are over the age of 40, or who have heart disease risk factors (smoking, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol), or who have been sedentary and plan a major increase in activity.17 For many others, a simple health screening questionnaire ensures readiness to engage in training, work, or a job-related WCT.17 The FF did not have these risk factors and was not sedentary, but he was over the age of 40 and should have had a more recent medical evaluation than in 1999.

NFES 1109, Work Capacity Test Administrator’s Guide, addresses requirements and recommendations for performing the WCT Pack Test. It does not require a pre-WCT medical examination for all applicants.18 When a medical examination is required, no blood testing for lipids (i.e., hypercholesterolemia), glucose levels (i.e., diabetes mellitus), or exercise stress tests are recommended.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1051, Wildland Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, addresses medical and job-related physical performance requirements for entry-level wildland fire fighters. It recommends that the jurisdictional authority determine what those requirements shall be.19

NFPA 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, establishes medical requirements for structural fire fighters.20 It requires candidate and member medical evaluations prior to training programs or participation in departmental emergency response activities. These requirements could be modified for individuals involved in suppressing wildland fires.20

Use of Exercise Stress Tests (EST) to Screen for CAD. Could this FF’s underlying CAD have been identified earlier? To reduce the risk of sudden cardiac arrest or other incapacitating medical conditions among fire fighters, NFPA 1582 was developed.20 To screen for CAD, NFPA 1582 recommends an EST for asymptomatic fire fighters with two or more of the following risk factors for CAD:

- Family history of premature (first degree relative less than age 60) cardiac event

- Hypertension (diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Cigarette smoking

- Hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dL).20

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) states that conducting EST on asymptomatic individuals is “less well established” (Class IIb) for the following groups:

- Evaluation of persons with multiple risk factors as a guide to risk-reduction therapy with the risk factors essentially the same as the NFPA listed above.

- Evaluation of asymptomatic men older than 45 years, and women older than 55 years who are:

- sedentary and plan to start vigorous exercise

- involved in occupations in which impairment might jeopardize public safety (e.g., fire fighters)

- at high risk for CAD due to other diseases (e.g., peripheral vascular disease and chronic renal failure).21

Another organization involved with EST is the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). To obtain medical certification for a commercial drivers license, DOT recommends EST for drivers over the age of 45 with more than two CAD risk factors.22 Finally, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend EST for asymptomatic individuals, even those with risk factors for CAD; rather, they recommend diagnosing and treating modifiable risk factors (hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes).23 The USPSTF indicates that there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening middle age and older men or women in the general population but notes that, “screening individuals in certain occupations (pilots, truck drivers, etc.) can be recommended on other grounds, including the possible benefits to public safety.”23 The National Wildfire Coordinating Group guidelines (NFES 1596 and NFES 1109) follow the US Forest Service (USFS) guidelines. Neither organization requires an EST for asymptomatic individuals.

Since the FF had no known CAD risk factor for EST determination, an EST would NOT have been recommended by NFPA, AHA/ACC, DOT, or the USPSTF. In addition, since the FF did not have any known heart disease risk factors as defined by the ACSM, the NFES 1109 and NFPA 1051 would not have required a medical evaluation, while NFES 1596 does because the FF was over the age of 40. However, a mandatory comprehensive wellness/fitness program, including weight reduction, dietary education, and exercise would have benefited the FF.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations 1–2 below address safety issues unique to this event. Recommendations 3–5 are preventive measures often recommended by fire service groups to reduce the risk of on-the-job heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters. These recommendations should be implemented by the SCA.

Recommendation #1: Check WCT participants’ vital signs before testing.

NFES 1109, Work Capacity Test Administrator’s Guide, requires that an EMT (or someone with equivalent qualifications) observe candidates during and after the test to provide emergency medical assistance, if needed.18 The EMT should take participant vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, and respirations) before and after the WCT to ensure that the participant does not have a precluding condition prior to the test and that the participant’s vital signs return to normal levels after the test. This was not performed, but it was unlikely to have influenced this event.

Recommendation #2: Modify the Health Screening Questionnaire (HSQ) in the Pacific Regional Handbook to include all cardiovascular risk factors identified by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC).

The HSQ, located in the BIA Pacific Regional Handbook, Part 90, Chapter 3, does not cover all CAD risk factors identified by the AHA/ACC. Specifically, the HSQ includes no question regarding smoking status and weight. We suggest replacing these yes/no questions with questions that require the fire fighter to enter specific information (Attachment 4). The WCT Administrator would then make the decision whether the fire fighter was fit to perform the WCT. Using these questions puts more responsibility on fire fighters to know the results of their medical tests.

|

Attachment 4

|

History:

Current height: |

Recommendation #3: Consider providing pre-placement and periodic medical evaluations to ALL fire fighters consistent with NFPA 1582 or equivalent to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

Guidance regarding the content and frequency of periodic medical evaluations and examinations for fire fighters can be found in NFPA 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments,20 and in the report of the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFF/IAFC) wellness/fitness initiative.24 The SCA is not legally required to follow any of these standards.

The success of medical programs hinges on protecting the affected fire fighter. The Agency must 1) keep the medical records confidential, and 2) if the fire fighter is not medically qualified for active fire fighting duties, notify the fire fighter of the medical findings.

The BIA/SCA is currently providing both pre-placement and periodic medical evaluations only to fire fighters over the age of 45 due to budget limitations.

Recommendation #4: Ensure that fire fighters are cleared for duty by a physician knowledgeable about the physical demands of fire fighting.

Physicians providing input regarding medical clearance for fire fighting duties should be knowledgeable about the physical demands of fire fighting and familiar with the consensus guidelines published in NFPA 1582, NFPA 1051, NFES 1596, and NFES 1109. To ensure physicians are aware of these guidelines, we recommend that the SCA provide the contract and private physicians of its members with a copy of these guidelines. In addition, we recommend that all return-to-work clearances be reviewed by an Agency-contracted physician. This decision requires knowledge not only of the member’s medical condition but also of the member’s job duties. Frequently, private physicians are not familiar with a member’s job duties or with guidance documents such as NFPA 1582, NFPA 1051, NFES 1596, and NFES 1109. Thus, the final decision regarding medical clearance for return to work lies with the SCA with input from many sources including the employee’s private physician.

Recommendation #5: Ensure that fire fighters participate in a mandatory wellness/fitness program designed for wildland fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

Physical inactivity is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for CAD in the United States. Additionally, physical inactivity, or lack of exercise, is associated with other risk factors, namely obesity and diabetes.25 For structural fire fighters, NFPA 1500, NFPA 1583, and the IAFF/IAFC Wellness/Fitness Initiative address wellness/fitness issues. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, requires a wellness program that provides health promotion activities for preventing health problems and enhancing overall well-being.26 NFPA 1583, Standard on Health-Related Fitness Programs for Fire Fighters, provides the minimum requirements for a health-related fitness program.27 In 1997, the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) and the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) published a comprehensive Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative to improve fire fighter quality of life and maintain physical and mental capabilities of fire fighters. Ten fire departments across the United States joined this effort to pool information about their physical fitness programs and to create a practical fire service program. They produced a manual and a video detailing elements of such a program.24

For wildland fire fighters, NFES 1596 and NFPA 1051 address wellness/fitness issues. NFES 1596, Fitness and Work Capacity, provides information on fitness, work capacity, nutrition, hydration, the environment, work hardening, and injury prevention for wildland fire fighters.17

NFPA 1051, Wildland Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, addresses medical and job-related physical performance requirements for entry-level wildland fire fighters. It recommends that the jurisdictional authority determine what those requirements shall be.19

The SCA should ensure that local FDs are aware of the physical demands of wildland fire fighting and that the wildland fire fighters participate in a wellness/fitness program designed for wildland fire fighters.

REFERENCES

- Siegel RJ [1997]. Myocardial Hypertrophy. In: S. Bloom (ed). Diagnostic Criteria for Cardiovascular Pathology Acquired Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Lippencott-Raven, pp. 55-57.

- Armstrong WF and Feigenbaum H [2001]. Echocardiography. In: Braunwald E, Zipes DP, and Libby P, eds. Heart disease. 6th Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 167.

- National Heart Lung Blood Institute [2003]. Obesity education initiative. World Wide Web (Accessed September 2003.) Available from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/BMI/bmicalc.htmexternal icon. (Link Updated 1/16/2013)

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group [2000]. Wildland and prescribed fire qualification system guide. Missoula MT: National Wildfire Coordinating Group. NWCG 310-1.

- Meyerburg RJ, Castellanos A [2001]. Cardiovascular collapse, cardiac arrest, and sudden cardiac death. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 228-233.

- AHA [1998]. AHA Scientific Position, Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association.

- Jackson E, Skerrett PJ, and Ridker PM [2001]. Epidemiology of arterial thrombosis. In: Coleman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VIJ, et al. eds. Homeostasis and thrombosis: basic principles and clinical practice. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Libby P [2001]. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. p.1378.

- Shah PK [1997]. Plaque disruption and coronary thrombosis: new insight into pathogenesis and prevention. Clin Cardiol 20 (11 Suppl2): II-38-44.

- Fuster V, Badimon JJ, Badimon JH [1992]. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. N Eng J Med 326:242-250.

- Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, et al. [1993]. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med 329:1684-1690.

- Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, et al. [1993] Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. N Eng J Med 329:1677-1683.

- Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T [1984]. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Eng J Med 311:874-877.

- Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, et al. [1992] Modifiers of timing and possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Phase II (TIMI II) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:1049-1055.

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. [1993]. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25(1):71-80.

- American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal [1971]. Ergonomics guide to assessment of metabolic and cardiac costs of physical work. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 560-564.

- NWCG [1997]. Fitness and work capacity. Missoula MT: National Wildfire Coordinating Group. NFES 1596.

- NWCG [2003]. Work capacity test administrator’s guide. Missoula MT: National Wildfire Coordinating Group. NFES 1109.

- NFPA [2002]. Standard for wildland fire fighter professional qualifications. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1051.

- NFPA [2003]. Standard on comprehensive occupational medical program for fire departments. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1582.

- Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, Mark DB, McCallister BD, Mooss AN, O’Reilly MG, Winters WL Jr, [2002]. ACC/AHA guidelines update for exercise testing: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). American College of Cardiology Web site. Available at: http://content.onlinejacc.org/data/journals/JAC/22975/21642.pdfpdf iconexternal icon. (Link Updated 10/28/2013)

- U.S. Department of Transportation [1987]. Medical advisory criteria for evaluation under 49 CFR Part 391.41 (http://www.fmcsa.dot.gov//rules-regulations/administration/fmcsr/fmcsrruletext.aspx?reg=391.41external icon). (Link Updated 1/16/2013) Conference on cardiac disorders and commercial drivers – FHWA-MC-88-040, December. Available at http://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/documents/cardio.pdf (Link no longer available 5/12/2015). Accessed May 2002.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [1996]. Guide to clinical prevention services, 2nd Ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, pp. 3-15.

- IAFF, IAFC [2000]. The fire service joint labor management wellness/fitness initiative. Washington, D.C.: International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs.

- Plowman SA and Smith DL [1997]. Exercise physiology: for health, fitness and performance. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- NFPA [2002]. Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1500.

- NFPA [2000]. Standard on health-related fitness programs for fire fighters. Quincy MA: National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1583.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by and the report written by:

Tommy N. Baldwin, MS

Safety and Occupational Health Specialist

Mr. Baldwin, a National Association of Fire Investigators (NAFI) Certified Fire and Explosion Investigator, an International Fire Service Accreditation Congress (IFSAC) Certified Fire Officer I, and a Kentucky Certified Fire Fighter and Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), is with the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Cardiovascular Disease Component located in Cincinnati, Ohio.

This page was last updated on 06/29/05.