Fire Fighter Suffers Fatal Heart Attack at Two-Alarm Structure Fire - Texas

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2003-02 Date Released: September 12, 2003

SUMMARY

On December 5, 2002, a 51-year-old male career Captain responded on his Engine company to a working fire in the attic of a two-story dwelling. After assisting with fire extinguishment on the second floor, he suddenly collapsed. Crew members carried him down the stairs and into the front yard, assessed him, and found him to be unresponsive, not breathing, and pulseless. Approximately 46 minutes later, despite cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and advanced life support (ALS) administered on the scene and at the hospital, the victim died. The autopsy revealed atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease. The death certificate listed “atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease” as the immediate cause of death.

The following recommendations address some general health and safety issues. This list includes some preventive measures that have been recommended by other agencies to reduce the risk of on-the-job heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters. These selected recommendations have not been evaluated by NIOSH, but represent published research, or consensus votes of technical committees of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) or fire service labor/management groups.

- Provide mandatory annual medical evaluations consistent with NFPA 1582 to ALL fire fighters to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

- Consider incorporating exercise stress tests into the Fire Department’s medical evaluation program.

- Provide fire fighters with medical evaluations and clearance to wear self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

- Phase in a mandatory wellness/fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

Although unrelated to this fatality, the Fire Department should consider this additional recommendation based on safety and economic considerations:

- Discontinue the routine use of annual chest x-rays.

INTRODUCTION & METHODS

On December 5, 2002, a 51-year-old male Captain lost consciousness while assisting with fire extinguishment at a two-alarm dwelling fire. Despite CPR and ALS administered by crew members, the ambulance crew, and in the emergency department, the victim died. NIOSH was notified of this fatality on December 6, 2002, by the United States Fire Administration. On December 9, 2002, NIOSH contacted the affected Fire Department to initiate the investigation. On February 3, 2003, a Safety and Occupational Health Specialist and an Occupational Nurse Practitioner from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Team traveled to Texas to conduct an on-site investigation of the incident.

During the investigation NIOSH personnel interviewed:

- The Deputy Chief of Training

- The Fire Department Assistant Chaplain

- The victim’s wife

During the site-visit NIOSH personnel reviewed:

- Fire Department policies and operating guidelines

- Fire Department training records

- The Fire Department annual report for 2001

- Fire Department incident report

- Emergency medical service (ambulance) incident report

- Hospital emergency department report

- Fire Department physical examination protocols

- Death certificate

- Autopsy record

- Past medical records of the deceased

INVESTIGATIVE RESULTS

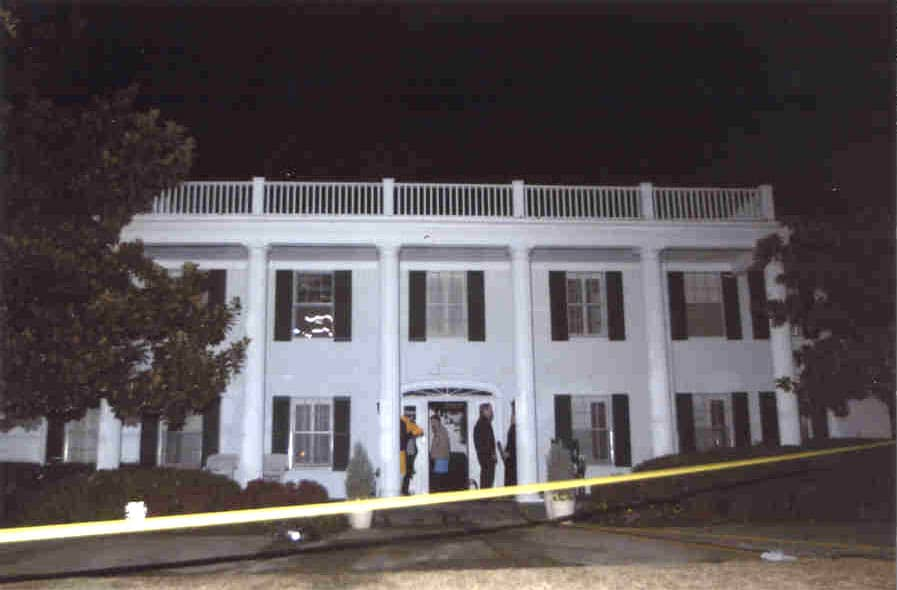

Incident. On December 5, 2002, the Captain (the victim) reported to work at Engine 56’s quarters at approximately 0620 hours. After breakfast, he spent most of the day assisting his Battalion Chief prepare the leave schedule for 2003. Over the course of the day, the victim and his crew responded to three alarms: a motor vehicle accident (1355 hours), a medical emergency (1619 hours), and the structure fire at which he collapsed. At 2010 hours, Engine 56, Engine 22, Engine 20, Truck 20, Rescue 22, and Battalion Chief 2 (BC-2) (20 personnel total) were dispatched to a structure fire. Engine 56 was the first unit to arrive on the scene (2014 hours), parked directly in front of the residence, and reported “smoke showing.” See Table 1 for a timeline of the response. The structure was a 3,570 square foot, two-story, single-family dwelling of brick veneer construction (see Photograph). The fire was confined to the attic.

The Captain investigated the location of the fire and ordered his crew to advance a 1¾-inch pre-connected hose line. The Captain and two fire fighters (wearing full turnout gear and SCBA [on air]) took the attack line up the interior stairs to the second floor. BC 2 arrived on-scene, assumed command, and set up the command post in front of the residence. Truck 7 and Battalion Chief 4 were dispatched at 2015 hours. Engine 20 arrived (2016 hours) and entered the structure to assist Engine 56. Truck 20 arrived on the scene (2017 hours) and, upon entering the structure, set ladders in place and pulled ceilings in the upstairs bedroom so the fire could be accessed. After directing a stream of water into the attic, the Captain passed the hose line to a fire fighter from Engine 20. The Captain pulled slack in the hose so that the fire fighter could adequately reach into the attic area with the hose stream. Engine 22 arrived on the scene and laid a 5-inch supply line from a hydrant to Engine 56. At this time the fire broke through the roof and Command requested a second alarm.

At 2017 hours, a second alarm was transmitted and Engine 7, Engine 13, Engine 41, Truck 41, Truck 57, Battalion Chief 7, Rescue 20, Battalion Chief 3, Deputy Chief 806, and the EMS shift duty officer were dispatched.

As the Engine 20 fire fighter was directing a stream of water into the attic, Engine 22 was also stretching a 1¾-inch pre-connected hose line into the structure and up the stairs as a backup. The Captain directed a fire fighter to get a pike pole in order to pull the ceiling in the adjoining room. Once the attic fire was knocked down, fire fighters repositioned the hose line to attack the fire in another location. The Captain ordered that the backup hose line be charged. The Captain then reached for his radio and suddenly collapsed backward, falling against the leg of a nearby fire fighter from Truck 20. At first the fire fighter thought the Captain had tripped, but when the Captain did not move, the fire fighter advised “Man down.” Command called for Rescue 22 to report to the command post. Due to apparatus placement, the crew from Rescue 22 had to leave the vehicle and proceed with their gear on foot to the scene.

Nearby crew members immediately carried the Captain down the stairs and into the front yard (approximately 2018 hours). Crew members removed the Captain’s SCBA and turnout coat. Initial assessment revealed the victim was unresponsive, not breathing, and pulseless. CPR (chest compressions and assisted ventilations via mouth-to-mouth) was begun. An automated external defibrillator (AED) was connected to the victim, revealing the need to defibrillate. He was immediately shocked two separate times.

Rescue 22 and Rescue 20 arrived at the Captain’s location and began ALS treatment (intubation [a breathing tube placed into the victim’s windpipe and correct placement confirmed using bilateral breath sounds and capnography] and placing an intra-venous [IV] line). A cardiac monitor was connected to the Captain, which revealed pulseless electrical activity (PEA). ALS medications were administered. An Engine 56 crew member drove Rescue 20 around the block in order to get to the scene. The Captain was placed onto a backboard, loaded into Rescue 20, and transported to a nearby hospital. His intubation was confirmed for proper placement two times. Enroute, the cardiac monitor revealed PEA and CPR was continued. Rescue 20 arrived at the hospital at 2040 hours.

Inside the hospital emergency department, a cardiac monitor revealed Ventricular Fibrillation. The victim was defibrillated twice without success. Another round of IV medications was administered, proper intubation was confirmed by bilateral breath sounds and a Carbon Dioxide detection device, and the Captain’s heart rhythm converted to asystole (no heartbeat). CPR and ALS measures continued without a change in rhythm until 2103 hours, at which time he was pronounced dead and resuscitation efforts were discontinued.

Medical Findings. The death certificate, completed by the Deputy Chief Medical Examiner, listed “Atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease” as the immediate cause of death. The carboxyhemoglobin level was less than one percent, indicating inhaled carbon monoxide was not a factor in his death. Pertinent findings from the autopsy, performed by the Deputy Chief Medical Examiner, on December 6, 2002, included:

- Severe occlusive coronary artery disease

- “90% narrowing of the right coronary artery”

- “90% narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery”

- “85% narrowing of the left circumflex”

- Remote infarct of the posterior wall of the left ventricle and the posterior aspect of the interventricular septum

- Cardiomegaly (an enlarged heart) weighing 560 grams (normal is less than 400 grams)

- Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (free wall width 1.5 centimeters thick)

Medical History. The Captain had the following risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD): advancing age (>45 years old), male gender, family history of CAD, high blood cholesterol, and high blood pressure. The victim was currently taking prescription medication for his high blood pressure and cholesterol. Off duty, the Captain owned a roofing business. The victim exercised both on and off duty performing aerobic activity such as walking. On autopsy the Captain weighed 198 pounds and was 70 inches tall, giving him a body mass index (BMI) of 28.4 kg/m2 (A BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 is overweight, while BMI above 30 kg/m2 is considered obese).29

In July 1989, the Captain experienced chest pain and was admitted to a local hospital where it was determined he had a myocardial infarction (MI). A cardiac catheterization was performed and a blockage was found in his right coronary artery which was opened by a percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). At that time it was noted that his heart was enlarged (cardiomegaly) with a normal ejection fraction of 57% (a measure of how well his heart pumps blood). The Captain returned two weeks later and completed a normal submaximal moderate level exercise stress test (EST) (nine metabolic equivalents [METS] in eight minutes using the Bruce protocol).

Long term follow-up consisted of frequent cardiologist visits with thallium imaging ESTs. These tests failed to show any evidence of persistent ischemia until May 2002. In May 2002, his thallium EST showed hypokinesis in the area of his old myocardial infarction and a new area of reduced perfusion in the inferior/posterior basal walls and portions of the posterolateral wall, which was interpreted by the radiologist as being artifact or artificially created. The EKG portion of the test presented ST changes at peak exercise consistent with ischemia, but which resolved quickly during recovery. The cardiologist interpreted this “rapid resolution” as lessening the likelihood of the changes being due to ischemia. The Captain also was found to possess an ejection fraction of 34% (normal, typically above 50%). Despite these three new findings (new defect on thallium EST, ischemic EKG changes at peak exercise, and a new reduction in his ejection fraction), no work restrictions were given, and he was cleared for full duty.

According to his wife and crew members, the victim had no complaints of chest pains or any other heart-related illness. During the day of the incident, the victim did not report any symptoms suggestive of angina or heart attack to anyone.

DESCRIPTION OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT

At the time of the NIOSH investigation, the Fire Department consisted of 1,600 uniformed personnel and served a population of 1,100,000 residents in a geographic area of 378 square miles. There are 55 fire stations.

In fiscal year 2001, the Department responded to 253,142 calls: 148,940 medical calls, 63,496 medical/rescue calls, 26,397 other calls, 11,858 fire alarm calls, 6,740 investigation calls, 5,549 service calls, 4,480 structure fires, 3,784 vehicle fires, 2,637 hazardous condition calls, 1,690 other fire calls, and 1,329 grass fires. These include 73 two-alarm calls, 26 three-alarm calls, 9 four-alarm calls, and 1 six-alarm call. There were an average of 408 daily emergency medical dispatches and 285 daily fire equipment dispatches. The day of the incident, the victim responded to three calls: a motor vehicle accident at 1355 hours (cancelled), a heart attack at 1619 hours (assist Rescue 20), and the structure fire (2010 hours) where he collapsed.

Training. The Fire Department requires all new fire fighter applicants to have 45 college credit hours with a “C” average or better, pass a written civil service test, a math and reading test, a physical ability test, a polygraph test, a background check, a drug test, and a physical examination prior to being hired. Newly hired fire fighters are then sent to the 15-month fire fighter-paramedic training course at the City Fire Academy to become certified as a Fire Fighter-Paramedic.

Recurrent training occurs daily on each shift. The State minimum requirement for fire fighter certification is the 468-hour Fire Fighter I and II course and the 40-hour Emergency Care-Ambulance course. Career fire fighters must be State certified within one year of employment. The State also requires a minimum of 20 hours training for recertification. Annual re-certification is required for hazardous materials; while EMT and paramedic recertification is bi-annual. The victim was certified as a Master Fire Fighter, Fire Officer 1, Hazardous Materials Operations, Crash-Fire-Rescue, and Instructor Intermediate. He had almost 31 years of fire fighting experience.

Pre-placement Evaluations. The Department requires a pre-placement medical evaluation for all new hires, regardless of age. Components of this evaluation include the following:

- A complete medical history

- Physical examination

- Blood tests: Complete Blood Chemistry (CBC)

- Pulmonary function test (PFT)

- Audiogram

- Vision screen

- Chest x-ray

- Urinalysis

These evaluations are performed by the City physician. Once this evaluation is complete, the City physician makes a determination regarding medical clearance for fire fighting duties and forwards this decision to the City’s personnel director.

Periodic Evaluations. Periodic medical evaluations are required by this Department for selected members. The hazardous materials (HazMat) fire fighters and Weapons of Mass Destruction Team (Medical Strike Team) members are evaluated yearly. The Driver-Engineers are evaluated every other year. Components of the evaluation for Hazmat and Medical Strike Team are:

- A complete medical history

- Physical examination

- Blood tests: CBC and heavy metals

- PFT

- Chest x-ray

- Maximal stress treadmill exercise test with 12 point lead EKG

- Urinalysis

- Audiogram

- Vision screen

Components of the periodic medical evaluation for Driver-Engineers include the following:

- Blood pressure

- Urinalysis

- Audiogram

- Vision screen

The City physician performs the periodic medical evaluations for Driver-Engineers. A contractor performs the evaluations for the Hazmat fire fighters and Medical Strike Team. Medical clearance for self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) use and for fire suppression is not required for all fire fighters. If an employee is injured at work, or is ill and off work for more than three shifts, the employee is evaluated by their personal physician, who forwards their recommendation regarding “return to work” to the City physician, who makes the final determination. The victim was cleared for duty by his Cardiologist following his angioplasty on January 31, 1990.

Exercise (strength and aerobic) equipment is located in the fire stations. Mandatory wellness/fitness programs are in place for the Department, however the type of exercise performed is left to the individual fire fighter. Health maintenance programs (smoking cessation, cholesterol reduction, employee assistance programs, etc.) are available from the City.

DISCUSSION

In the United States, coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis) is the most common risk factor for cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.1 Risk factors for its development include age over 45, male gender, family history of coronary artery disease, smoking, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, obesity, physical inactivity, and diabetes.2,3 The victim had five of these risk factors: advancing age (>45 years old), male gender, family history of CAD, high blood pressure, and high blood cholesterol. In addition, based on his previous MI resolved with a PTCA, he was known to have CAD diagnosed in 1989.

The narrowing of the coronary arteries by atherosclerotic plaques occurs over many years, typically decades.4 However, the growth of these plaques probably occurs in a nonlinear, often abrupt fashion.5 Heart attacks typically occur with the sudden development of complete blockage (occlusion) in one or more coronary arteries that have not developed a collateral blood supply.6 This sudden blockage is primarily due to blood clots (thrombosis) forming on the top of atherosclerotic plaques. Blood clots, or thrombus formation, in coronary arteries are initiated by disruption of atherosclerotic plaques. Certain characteristics of the plaques (size, composition of the cap and core, presence of a local inflammatory process) predispose the plaque to disruption.6 Disruption then occurs from biomechanical and hemodynamic forces, such as increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, increased catecholamines, and shear forces, which occur during heavy exercise.7,8 At autopsy, no thrombus was present, however the deceased did have significant CAD.

Firefighting is widely acknowledged to be one of the most physically demanding and hazardous of all civilian occupations.9 Firefighting activities are strenuous and often require fire fighters to work at near maximal heart rates for long periods. The increase in heart rate has been shown to begin with responding to the initial alarm and persist through the course of fire suppression activities.10–12 Even when energy costs are moderate (as measured by oxygen consumption) and work is performed in a thermoneutral environment, heart rates may be high (over 170 beats per minute) owing to the insulative properties of the personal protective clothing.13 Epidemiologic studies have found that heavy physical exertion sometimes immediately precedes and triggers the onset of acute heart attacks.14–17 During the day, the victim responded to two alarms, however his crew was cancelled on the first call and his activity was light on the second call. At the structure fire, the victim wore full turnout gear and SCBA (on air) during fire extinguishment operations at a two-alarm dwelling fire. His activities ranged from walking up one flight of stairs to pulling a charged 1¾-inch hose line. This is considered a moderate level of physical exertion.18 The physical stress of responding to these alarms probably increased his heart rate and blood pressure thereby increasing his cardiac oxygen demand. This, along with his underlying CAD, was responsible for this fire fighter’s probable heart attack, subsequent cardiac arrest, and sudden death. The term “probable” is used because an acute (recent) heart attack can only be confirmed by one of the following:

- Blood test finding elevated cardiac iso-enzymes;

- On autopsy, thrombus (blood clot) formation in one of the coronary arteries;

- If there is a heart beat, characteristic findings on the EKG.

Unfortunately, the victim did not have blood taken in the emergency room for cardiac iso-enzymes, did not have a thrombus formation on autopsy, and he had no heart beat to show the characteristic findings of a heart attack on his EKG. However, his autopsy findings of marked atherosclerotic disease in three coronary arteries, and his clinical course were consistent with an acute heart attack leading to his sudden cardiac death.

To reduce the risk of heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters, the NFPA has developed guidelines entitled “Standard on Medical Requirements for Fire Fighters and Information for Fire Department Physicians,” otherwise known as NFPA 1582.19 NFPA 1582 recommends a yearly physical evaluation to include a medical history, height, weight, blood pressure, and visual acuity test.19 NFPA 1582 also recommends a thorough examination to include vision testing, audiometry, pulmonary function testing, a complete blood count, urinalysis, and biochemical (blood) test battery be conducted on a periodic basis according to the age of the fire fighter (less than 30: every 3 years; 30-39: every 2 years; over 40 years: every year). The Department requires a pre-placement medical examination for all new hires but does not require periodic medical evaluations for all fire fighters. Periodic medical evaluations are offered only to HazMat fire fighters, Driver-Engineers, and responders for weapons of mass destruction catastrophies.

NFPA 1582 also recommends, not as a part of the requirements but for informational purposes only, fire fighters over the age of 35 with risk factors for CAD be screened for obstructive CAD by an EST.19 In this case, within the past year, the victim had not only an EST but also a thallium nuclear stress test. On EKG, the EST presented with ST segment suggestive of ischemic changes and the thallium scan suggested ischemia in the anterolateral and posterolateral wall and in the anteroapex portion of the heart. Unfortunately, this was interpreted as artifact. The ejection fraction was 34% (normal 50% and higher). No work restrictions were completed for the Captain.

If the Captain had been examined by a physician familiar with NFPA 1582, he probably would have been precluded from duty as a firefighter. The Captain had two “Category B” medical conditions (a medical condition which could preclude a person from performing in a training or fire suppression activity because the condition presents a risk to themselves or others). The “Category B” conditions included: CAD and cardiac hypertrophy. Particularly concerning were the Captain’s new changes on his EST (both on EKG and thallium scan), and the newly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. This should have lead to restricted duty until a cardiac catheterization could be performed.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The following recommendations address health and safety generally. This list includes some preventive measures that have been recommended by other agencies to reduce the risk of on-the-job heart attacks and sudden cardiac arrest among fire fighters. These recommendations have not been evaluated by NIOSH, but represent published research, or consensus votes of technical committees of the NFPA or fire service labor/management groups.

Recommendation #1: Provide mandatory annual medical evaluations to ALL fire fighters to determine their medical ability to perform duties without presenting a significant risk to the safety and health of themselves or others.

Guidance regarding the content and frequency of periodic medical evaluations and examinations for fire fighters can be found in NFPA 1582, Standard on Medical Requirements for Fire Fighters and Information for Fire Department Physicians,19 and in the report of the International Association of Fire Fighters/International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFF/IAFC) wellness/fitness initiative.24 The Department is not legally required to follow any of these standards. Nonetheless, we recommend the City and Union work together to establish the content and frequency in order to be consistent with the above guidelines.

In addition to providing guidance on the frequency and content of the medical evaluation, NFPA 1582 provides guidance on medical requirements for persons performing fire fighting tasks. NFPA 1582 should be applied in a confidential, nondiscriminatory manner. Appendix D of NFPA 1582 provides guidance for Fire Department Administrators regarding legal considerations in applying the standard.

Applying NFPA 1582 also involves economic issues. These economic concerns go beyond the costs of administering the medical program; they involve the personal and economic costs of dealing with the medical evaluation results. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, addresses these issues in Chapter 8-7.1 and 8-7.2.25

The success of medical programs hinges on protecting the affected fire fighter. The Department must 1) keep the medical records confidential, 2) provide alternate duty positions for fire fighters in rehabilitation programs, and 3) if the fire fighter is not medically qualified to return to active fire fighting duties, provide permanent alternate duty positions or other supportive and/or compensated alternatives.

Recommendation #2: Consider incorporating exercise stress tests into the Fire Department’s medical evaluation program.

NFPA 1582 and the IAFF/IAFC wellness/fitness initiative both recommend at least biannual EST for fire fighters.19,24 They recommend that these tests begin at age 35 for those with CAD risk factors, and at age 40 for those without CAD risk factors. The EST could be conducted by the fire fighter’s personal physician, the City physician, or the Department’s contract physician. If the fire fighter’s personal physician or the contracted physician conducts the test, the results must be communicated to the City physician, who should be responsible for decisions regarding medical clearance for fire fighting duties.

Recommendation #3: Provide fire fighters with medical evaluations and clearance to wear self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

OSHA’s Revised Respiratory Protection Standard requires employers to provide medical evaluations and clearance for employees using respiratory protection.26 These clearance evaluations are required for private industry employees and public employees in States operating OSHA-approved State plans. Texas is not a State-plan State, therefore, public sector employers are not required to comply with OSHA standards. Nonetheless, we recommend following this standard to ensure fire fighters are medically cleared to wear SCBA on an annual basis.

Recommendation #4: Phase in a mandatory wellness/fitness program for fire fighters to reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease and improve cardiovascular capacity.

Physical inactivity is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for CAD in the United States. Additionally, physical inactivity, or lack of exercise, is associated with other risk factors, namely obesity and diabetes.27 NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, requires a wellness program that provides health promotion activities for preventing health problems and enhancing overall well-being.25 NFPA 1583, Standard on Health-Related Fitness Programs for Fire Fighters, provides the minimum requirements for a health-related fitness program.28 In 1997, the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) and the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) published a comprehensive Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness/Fitness Initiative to improve fire fighter quality of life and maintain physical and mental capabilities of fire fighters. Ten fire departments across the United States joined this effort to pool information about their physical fitness programs and to create a practical fire service program. They produced a manual and a video detailing elements of such a program.24 The Fire Department and the Union should review these materials to identify applicable elements for their Department. Other large-city negotiated programs can also be reviewed as potential models.

Recommendation #5: Discontinue the routine use of annual chest x-rays.

This finding did not contribute to the death of this Captain but was identified by NIOSH during the investigation. Specifically, according to NFPA 1582, “the use of chest x-rays in surveillance activities in the absence of significant exposures, symptoms, or medical findings has not been shown to reduce respiratory or other health impairment. Therefore, only pre-placement chest x-rays are recommended.” The chest x-rays being conducted by the Fire Department for the Hazmat and the Medical Strike Team expose incumbents to unnecessary radiation and represent an unnecessary expense for the Fire Department, and are not recommended by the OSHA Hazmat standard unless specifically indicated by the medical/occupational history.30

REFERENCES

1. Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL [2001]. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing, pp.228-233.

2. American Heart Association [2003]. Risk factors and coronary artery disease (AHA scientific position). World Wide Web (Accessed May 2003.) Available from: URL=http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4726

3. Jackson E, Skerrett PJ, and Ridker PM [2001]. Epidemiology of arterial thrombosis. In: Coleman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VIJ, et al eds. Homeostasis and thrombosis: basic principles and clinical practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

4. Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL [2001]. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 15th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing, p. 1378.

5. Shah PK [1997]. Plaque disruption and coronary thrombosis: new insight into pathogenesis and prevention. Clin Cardiol 20 (11 Suppl2):II-38-44.

6. Fuster V, Badimon JJ, Badimon JH [1992]. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. N Eng J Med 326:242-50.

7. Kondo NI, Muller JE [1995]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Risk 2(6):499-504.

8. Opie LH [1995]. New concepts regarding events that lead to myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drug Ther 9 Suppl 3:479-487.

9. Gledhill N, Jamnik, VK [1992]. Characterization of the physical demands of firefighting. Can J Spt Sci 17:3 207-213.

10. Barnard RJ, Duncan HW [1975]. Heart rate and ECG responses of fire fighters. J Occup Med 17:247-250.

11. Manning JE, Griggs TR [1983]. Heart rate in fire fighters using light and heavy breathing equipment: Simulated near maximal exertion in response to multiple work load conditions. J Occup Med 25:215-218.

12. Lemon PW, Hermiston RT [1977]. The human energy cost of fire fighting. J Occup Med 19:558-562.

13. Smith DL, Petruzzello SJ, Kramer JM, Warner SE, Bone BG, Misner JE [1995]. Selected physiological and psychobiological responses to physical activity in different configurations of firefighting gear. Ergonomics 38:10:2065-2077.

14. Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, Arntz HR, Schubert F, Schroder R [1993]. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med 329:1684-90.

15. Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ, Muller JE [1993]. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. N Eng J Med 329:1677-83.

16. Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T [1984]. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Eng J Med 311:874-7.

17. Tofler GH, Muller JE, Stone PH, Forman S, Solomon RE, Kratterud GL[1992]. Modifiers of timing and possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Phase II (TIMI II) Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:1049-55.

18. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal [1971]. Ergonomics guide to assessment of metabolic and cardiac costs of physical work. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 32(8):560-564.

19. NFPA [2000]. Standard on medical requirements for fire fighters and information for fire department physicians. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 1582-2000.

20. Michaelides AP, Psomadaki ZD, Dilaveris PE[1999]. Improved detection of coronary artery disease by exercise electrocardiography with the use of right precordial leads. New Eng J Med 340:340-345.

21. Darrow MD [1999]. Ordering and understanding the exercise stress test. American Family Physician 59(2):401-10.

22. Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Beasley JW, Bricker JT, Duvernoy WFC, Froelicher VF, Mark DB, Marwick TH, McCallister BD, Thompson PD, Winters WL Jr, Yanowitz FG (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Committee on Exercise Testing) [1997]. ACC/AHA guidelines for exercise testing: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 30:260-315.

23. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [1996]. Guide to clinical prevention services. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, pp. 3-15.

24.International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs [2000]. The fire service joint labor management wellness/fitness initiative. Washington DC: IAFF, IAFC.

25.NFPA [1997]. Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 1500-1997.

26. 29 CFR 1910.134. Code of Federal Regulations. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Respiratory Protection. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, Office of the Federal Register.

27. Plowman SA and Smith DL [1997]. Exercise physiology: for health, fitness and performance. Boston MA: Allyn and Bacon.

28. NFPA [2000]. Standard on health-related fitness programs for fire fighters. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 1583-2000.

29. National Heart Lung Blood Institute [2003]. Obesity education initiative. World Wide Web (Accessed March 2003.) Available from http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/

30. NIOSH [1993]. Occupational safety and health guidance manual for hazardous waste site activities. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 85-115.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This investigation was conducted by and the report written by Tommy N. Baldwin, MS, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist and Scott Jackson, RN Occupational Nurse Practitioner Mr. Baldwin and Mr. Jackson are with the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Cardiovascular Disease Component located in Cincinnati, Ohio.

| 2010 hours: | First alarm (E22, E20, E56, T20, Batt. 2, R22) dispatched |

| 2014 hours: | E56 arrived on the scene Batt. 2 arrived on the scene |

| 2015 hours: | T7, BC 4 dispatched |

| 2016 hours: | E20 arrived on the scene E22 arrived on the scene |

| 2017 hours: | T20 arrived on the scene Second alarm (E7, E13, E41, T41, T57, Batt. 7, R20, DC 806, Investigator, Batt. 3) dispatched Batt. 4 arrived on the scene T7 arrived on the scene |

| 2019 hours: | R22 arrived on the scene |

| 2023 hours: | E7 arrived on the scene R20 arrived on the scene |

| 2026 hours: | E13 arrived on the scene T57 arrived on the scene E41 arrived on the scene T41 arrived on the scene Batt. 7 arrived on the scene |

| 2040 hours: | R20 arrived at the hospital |