Volunteer Lieutenant Dies Following Structure Collapse at Residential House Fire - Pennsylvania

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2002-49 Date Released: November 21, 2003

SUMMARY

On November 1, 2002, a 36-year-old male volunteer Lieutenant (the victim) died after being crushed by an exterior wall that collapsed during a three-alarm residential structure fire. The victim was operating a handline near the southwest corner of the fire building where there was an overhanging porch. As the fire progressed, the porch collapsed onto the victim, trapping him under the debris. Efforts were being made by nearby fire fighters to free him when the entire exterior wall of the structure collapsed outward and he was crushed. The victim was removed from the debris within ten minutes, but attempts to revive him were unsuccessful and he was pronounced dead at the scene.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should:

- ensure that Incident Command (IC) continually evaluates the risk versus gain when deciding an offensive or defensive fire attack

- ensure that a collapse zone is established, clearly marked, and monitored at structure fires where buildings have been identified at risk of collapsing

- establish and implement written standard operating procedures (SOPs) regarding emergency operations on the fireground

- develop and coordinate pre-incident planning protocols throughout mutual aid departments

- implement joint training on response protocols throughout mutual aid departments

- ensure that an Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed and on-scene early in the fireground operation

Incident Scene

INTRODUCTION

On November 1, 2002, a 36-year-old male volunteer Lieutenant (the victim) died after being crushed by an exterior wall that collapsed during a three-alarm residential structure fire. On November 4, 2002, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this fatality. On December 9, 2002, three safety and occupational health specialists from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigated the incident. The NIOSH team visited and took photos of the fire scene, met with the Deputy State Fire Marshal, and conducted interviews with the officers and fire fighters who were present at the time of the incident. The team reviewed copies of the dispatch run sheets, witness statements, SOPs from the victim’s and the Incident Command department, the victim’s training records, and the death certificate.

Background The volunteer department in command of this incident is comprised of 30 fire fighters. The department has one station and serves a population of approximately 2,500 in a geographical area of five square miles.

The victim was from a volunteer department that was providing mutual aid during this incident. The mutual aid department has seven fire stations and is comprised of 50 volunteer fire fighters. It serves a population of approximately 13,000 in an area of about six square miles. The 36 year-old-victim had been a volunteer fire fighter with this department for 22 years and served 10 years as an officer.

Training The victim had over 500 hours of training that included NFPA Fire Fighter Levels I and II, First Responder, Incident Command, Advanced Firefighting, Emergency Medical Technician, Search and Rescue, and Live Fire training.

Equipment and Personnel There were six departments on the scene prior to the collapse. Units and apparatus arrived as follows:

Initial Alarm – 2300 Hours –

Incident Command Volunteer Department

- Two Officers, the Chief and Assistant Chief, arrived via separate privately owned vehicles (POVs)

- Engine 312

- Tanker 313

- Ambulance 314

Two Mutual Aid Volunteer Departments

- Engine 111

- Cascade 112

- Rescue 193

- Engine 352

- Tanker 354

Units dispatched from the first alarm arrived on scene from 2304 hours to 2316 hours.

Second Alarm – 2308 Hours

Incident Command Volunteer Department

- One Ambulance

- One Tanker

Five Mutual Aid Volunteer Departments

- One Ambulance

- Four Tankers

- Two Engines

- One Ladder Truck

- One Cascade

Units dispatched from the second alarm arrived on scene from 2310 to 2350 hours. Approximately 50 fire fighters were on the scene when the collapse occurred at 2354 hours. A third alarm was immediately requested following the collapse. Four additional departments and Lifeflight responded.

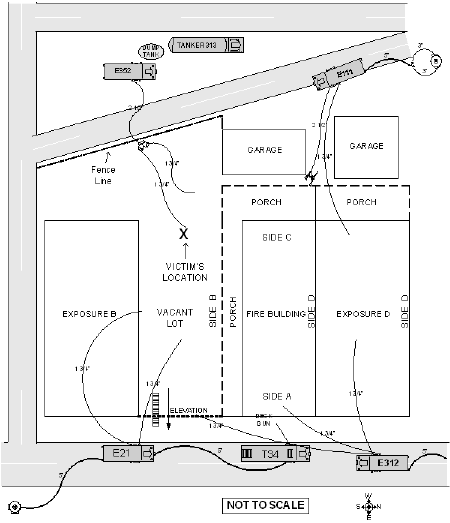

Structure The structure was a wood-frame balloon construction. It was built during the early 1800’s and had been remodeled several times. Homes in this block were originally built as row houses and at one time there was a dwelling that connected the fire building and Exposure B (Diagram 1). The fire building, Exposure B and Exposure D were very similar in construction. At the time the fire occurred, Exposure D was being used as a storage area for vending equipment and other miscellaneous items.

The exterior walls were wood covered by clapboard and aluminum siding. The pitched roof was made of rough-cut wooden rafters covered by tin sheets. The interior walls consisted of 2 by 4-inch wood studs covered by lath and plaster or paneling. The ceilings were 12 by 12-inch acoustic tile over lath. The hardwood floors were supported by 2 by 10-inch rough-cut lumber floor joists and some areas were carpeted.

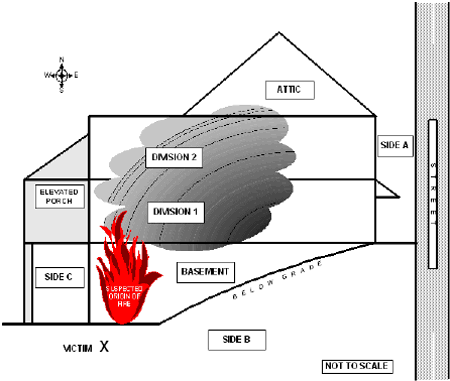

The structure was built into a sloping hillside and had three habitable levels topped by an attic storage area (Diagram 2). Total combined living space measured approximately 4,680 square feet. The first floor (Division 1) had living areas, a kitchen, bathroom, office, laundry, and indoor access to an elevated porch from Side C. Entry to the first floor was made from street level at the front of the house. The second floor (Division 2) had four bedrooms, one bathroom, and was accessible from the first floor by an internal staircase that was located at the front of the house. There was also an exterior stairway attached to the north-facing outer wall of Exposure D that led from street level up to Division 2. The basement was being used as separate living quarters and had a living room, bathroom, bedroom, kitchen, and furnace room. Both the fire building and Exposure D had an overhanging porch from the 2nd level attached on Side C (Photo 1). The porch wrapped around B/C corner and extended the entire length of side B of the fire building. Witnesses reported that at the time of the fire, the porch was being used to store many miscellaneous items including a clothes washer and dryer. From the area under the porch there was direct access to a garage that sat behind the dwelling. The garage opened into an alley where fire suppression apparatus were staged during the fire. The fire building was occupied by one tenant who was home at the time the fire started but escaped on his own prior to the start of fire-suppression activities. The structure was not equipped with sprinklers or smoke detectors.

Weather The temperature at the time the fire occurred was approximately 30° F. A mist was reported with no negligible wind.

INVESTIGATION

Alarm and Size-Up Information

On October 31, 2002, at 2300 hours, a volunteer department was dispatched to a working house fire. Arriving first on the scene at 2304 hours were two officers, the Chief and Assistant Chief who lived nearby and drove their personal vehicles to the incident site. The officers immediately began to survey the fire scene with the Assistant Chief going to the rear and the Chief remaining in front of the fire building to assume Incident Command (IC). During the initial size-up, the Assistant Chief reported that fire was showing in the B side basement area with flames extending about three feet under the porch toward Exposure B. The IC radioed that he observed fire extending upward from the basement area into Division 1 of the fire building and that the area was showing heat damage. He also reported heavy smoke in Divisions 1, 2, and the attic of the fire building with smoke extending into Exposure D. The IC radioed dispatch and requested a second alarm.

At 2308 hours, the second alarm was sounded. Two ambulances, five tankers, two engines, one ladder truck, and a cascade unit responded from five volunteer mutual aid departments and the Incident Command department. The units arrived on the scene from 2310 to 2350 hours. There were approximately 50 fire fighters on the scene when the collapse occurred at 2354 hours.

At 2358 hours additional units and personnel were requested by the IC and a third alarm dispatched additional units.

Critical apparatus and activities on the fireground

Engine 312 (E312) was the first unit to arrive on the incident scene following the initial alarm. E312 connected to a hydrant at the northeast (A/D) corner and staged to the east (A) side of the structure. Two 1¾-inch preconnect handlines were pulled from E312. One was taken to the A/B corner of the fire building and directed to the flames on side B. The second handline was stretched to the fire building where fire fighters attempted to enter through the front door from side A, however flames and heat forced them to retreat. Fire fighters then took another 1¾-inch line from E312 into Exposure D through the front door. They entered Divisions 1, 2, and the basement to breach the common walls in an attempt to stop the fire spread. Fire fighters were operating in all three levels when several of them reported hearing a “thud.” All fire fighters immediately exited the building and found that the porch located on the B side of the structure had collapsed.

Engine 111 (E111) with the victim driving, an officer, and two fire fighters, arrived second and was sent to the rear (C/D) corner where they connected to a nearby hydrant. Fire fighters took a 1 ¾-inch line from E111 and entered Exposure D from the rear to check for fire extension. They reported seeing the crew from E312 that had entered from the front. Fire fighters from E111 set up a portable deluge gun off of E111 at the (C/D) corner. It was operating at approximately 500 to 600 gallons per minute and was aimed to concentrate on the upper floors of the fire building.

Tanker 313 (T313) was the third apparatus to arrive and was sent to the rear (C) side of the structure to set up the dump tank. Engine 352 (E352) directly followed T313 and was staged to the rear (B/C) area near the tanker. Two 1 ¾-inch lines were connected by a gated wye to a 2 ½-inch line that came off of E352. The victim was operating one of these 1 ¾-inch lines when the incident occurred.

Engine 21(E21) responded on the second alarm and was sent to a hydrant near the southeast (A/B) side of the fire building to run a forward lay for the Tower. Tower 34 (T34) staged on the street directly to the east of side A of the fire building where they set up a deck gun. The master stream was not put into operation until after the collapse and rescue. Two 1¾-inch handlines were pulled from Engine 21. Fire fighters stretched one line to the vacant lot area between the unattached Exposure B and the fire building. Two fire fighters were operating this handline when reportedly they heard a cracking noise, and fearing a collapse, quickly exited the area by traveling eastward and climbing up a ladder over a retaining wall to street level. They reported seeing the victim near the B/C corner of the fire building just seconds before the porch collapsed. The second handline was taken into the basement of exposure B where fire fighters directed the water stream toward heavy flames coming through windows on the B-side of the fire building. Fire fighters operating this handline reported seeing the victim near the B/C corner just prior to the collapse.

Victim activity on the fireground

The victim was near the B/C corner of the fire building attempting to knock down hot spots. He was nozzle-man on a 1 ¾-inch handline pulled from the gated wye off of the 2 ½-inch line from Engine 352. The line was becoming snagged on a nearby fence as he attempted to advance. A second fire fighter got behind the victim to guide the line around the fence just as the porch collapsed and the victim was pinned by the debris. The victim remained conscious and called out for help. Two fire fighters who were operating the other 1 ¾-inch line from the gated wye ran to the victim and immediately began attempts to free him. Just as they began, the entire B-side wall collapsed and they had to flee the area to avoid being struck by falling debris. As soon as possible following the collapse, fire fighters rushed to the area and began digging through the debris near a light that they believed was from the victim’s flashlight. The victim was recovered within ten minutes following the collapse. Efforts to revive him were not successful and he was pronounced dead at the scene at 0050 hours on November 1, 2002.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The coroner listed the cause of death as traumatic compressional asphyxia.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSIONS

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure that Incident Command (IC) continually evaluates the risk versus gain when deciding an offensive or defensive fire attack.1-4

Discussion: The Incident Commander must consider, upon arrival and throughout the incident, whether the operation is to be conducted in an offensive or defensive mode. According to the International Fire Service Training Association, offensive and defensive strategies are defined as:

Offensive Fire Attack (Offensive Mode) – Aggressive, usually interior, fire attack that is intended to stop the fire at its current location. As a general rule, the IC should extend an offensive attack only where and when conditions permit, and adequate resources are available.

Defensive Fire Attack (Defensive Mode) – Exterior fire attack with emphasis on exposure protection. The commitment of a fire department’s resources to protect exposures when the fire has progressed to a point where an offensive attack is not effective.

According to Brunacini, there are several factors that can be used to assess fireground conditions and determine fire attack strategy. Six factors are listed below.

- Fire Extent and Location – How much of the building and what part of the building is involved? During initial size up at this incident, it was reported that fire was showing in the B side basement area with flames extending about three feet under the porch toward Exposure B. Fire was also observed extending upward from the basement area into Division 1 of the fire building and the area was showing heat damage. Heavy smoke was reported in Divisions 1, 2, and the attic of the fire building with smoke extending into Exposure D.

- Fire Effect on the Building – What are the structural conditions? The structure was a wood-frame balloon construction. It was built during the early 1800’s and had been remodeled several times, including the addition of an elevated porch the entire length of side B. The exterior walls were wood covered by clapboard and aluminum siding.

- Savable Occupants – Is there anyone alive to save? The lone occupant was witnessed exiting the structure prior to the arrival of the first apparatus.

- Savable Property – Is there any property left to save? Fire conditions prohibited an initial interior attack into the fire building. Fire fighters entered Exposure D to halt the fire spread.

- Entry and Tenability – Can fire personnel get into the building and stay in? Crews were unable to make entry into the fire building because of the heat.

- Resources – Are sufficient resources available for the attack? According to witness statements and dispatch records, it is estimated that there were six departments, thirteen fire apparatus, four emergency medical service units, and approximately 50 fire fighters on the incident scene when the collapse occurred.

The offensive versus defensive command decision is an ongoing one, requiring the IC to reconsider these major factors throughout the attack. For example, the decision to begin a defensive attack may be based on the fact that the offensive attack strategy has been abandoned for reasons of personnel safety, and the involved structure has been conceded as lost. In addition to an interior attack, a fire fighting strategy should be considered offensive when manual suppression activities are being conducted within the boundaries of a collapse zone. Conditions reported from the initial attack, and continual evaluation of the risk factors, may have indicated the need for defensive operations. In this incident, offensive fire fighting operations continued until the collapse. A defensive strategy was never officially called.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should ensure that a collapse zone is established, clearly marked, and monitored at structure fires where buildings have been identified at risk of collapsing.5-8

Discussion: Upon arrival, and at any time during a structure fire, if size-up determines that structural integrity is questionable, a collapse zone must be established. A collapse zone is an area around and away from a structure in which debris might land if the structure fails. This area should be equal to the height of the building plus an additional allowance for debris scatter, and at a minimum should be equal to 1 ½-times the height of the building. For example, if the wall were 20 feet high, the collapse zone boundary should be established at least 30 feet away from the wall.

Knowledge of building construction and how fire reacts in a building can assist in making determinations of structural stability. In Dodson’s publication, “Fire Department Incident Safety Officer,” he outlines the following seven-steps to assist fire scene personnel in analyzing the potential for structure collapse.

1. Classify the type of construction.

The structure was a wood-frame balloon construction that was built in the early 1800’s. This one sentence identifies three distinct hazards associated with the potential for a structure collapse; (a) the building’s age, (b) type of construction, and (c) construction materials.

- According to Dunn in his book, “Collapse of Burning Buildings,” structural collapse during firefighting can be expected to increase and one factor contributing to the increase is the age of buildings. Older buildings can be weakened due to age. Structures may become badly deteriorated as wood shrinks and rots, and mortar loses its adhesive qualities. One estimate identifies 75 to 100 years as the age at which buildings begin to deteriorate and conditions may contribute to collapse. In this incident, the structure had been built nearly 200 years ago.

- This building was a wood-frame balloon construction. A hazard found in balloon construction is the vertical void between the wall studs. This void extends from the foundation sill to the attic cap and allows hidden fire and smoke that penetrate the wall space to spread vertically for two or three floors.

- In Dunn’s book he describes the combustible bearing wall that is constructed of 2 by 4-inch wood studs as the structural hazard of a wood-frame building. A wood-frame building is a bearing wall structure. The two side walls are usually bearing (supporting a load other than their own weight); the front and rear walls are usually non-bearing. Fire fighters should know which of the four enclosing walls of a burning wood building are the load-bearing walls that support the floors and roof. These walls are interconnected and the interior floors will collapse if the bearing walls fail during a fire. Conversely, an interior floor collapse may cause a bearing wall failure. It is important that fire fighters know that wood-frame buildings use smaller structural members to support larger structural members, and the weak link in this design is the smaller structural supports which are the 2 by 4-inch bearing walls. Flames coming out of several window openings of a side bearing wall should be treated with more caution than flames coming out of windows on the front or rear non-bearing wall. If flames are coming out of the windows, they are also destroying the wall in which the windows are located. Fire burning through or against a side wall is more likely to collapse the building than fire burning through several floors or the roof. In this incident, it was reported that fire fighters were in Exposure B directing suppression efforts at heavy flames coming out of the windows on side B of the fire building. The initial collapse was the porch on side B followed by a collapse of the entire wall.

2. Determine the degree of fire involvement.

Upon initial size up, heavy fire was reported in side C with flames showing from the basement area. Fire fighters from the first arriving unit attempted to enter the fire building from the entrance on side A but were forced to retreat because of the flames and heat. It was reported that the structure quickly became fully involved.

3. Visualize load imposition and load resistance.

A load is defined by Dunn as, “a force which acts upon a structure.” A dead load, live load, impact load, fire load, and a concentrated load can all be causal factors in structure collapse.

- A dead load is a fixed load that is created by the structure itself and all of the permanent equipment within. Walls, floors, columns, and girders are all part of a structural dead load. Air conditioning appliances, fire escapes, and suspended ceilings are examples of an equipment dead load. The porch that extended the entire B side of the fire building could be defined as a dead load

- A live load is a moving or movable load. Examples of a live load are the building occupants, the weight of fire fighters who are inside the structure, the added weight of the fire equipment, and the water discharge from hose streams. The weight of the water discharge from the portable deluge gun and hose streams would have contributed to the live load in this incident. Serious collapse danger exists when a large volume of water is discharged into a burning building. One gallon of water weighs approximately eight pounds. The portable deluge gun was operating at 500 to 600 gallons per minute which would equate to approximately 40,000 to 48,000 pounds of water weight after ten minutes of operation. Some of the water would vaporize or run off, but an undetermined amount would have been absorbed and the added weight would contribute to the collapse potential. Additionally, the force of water being discharged from a portable deluge gun can be a destabilizing factor.

- An impact load is a load applied suddenly to a structure. The pulsating flow from a master stream can cause a structure to collapse more readily than a steady, evenly applied load.

- A fire load is defined by Dunn as “the measure of maximum heat release when all combustible material in a given fire area is burned.” The content and structure of a building contribute to the fire load. The potential for structural collapse is directlyproportional to the fire load. The greater the fire load, the greater the possibility of structural collapse. In this incident, there was heavy fire reported upon initial size up and the structure was quickly fully involved.

- A concentrated load is found at one point or restricted within a limited area of the structure. The storage of heavy items on the porch such as the clothes washer and dryer may have caused a weight concentration that contributed to the porch instability and eventual collapse.

4. Evaluate time as a factor.

There is no absolute formula to predict collapse, but the longer fire burns in a building the more likely it is to collapse. The initial alarm was sounded at 2300 hours. The structure had been burning at least 54 minutes when the collapse occurred.

5. Determine the weak link.

A weak link may be trusses (floors/roofs), structural connections, or 2 by 4-inch bearing walls of a wood-frame structure that are used to support larger structural members.

6. Predict the collapse sequence.

This will assist in determining if walls will fall inward or outward, if the building can withstand a partial collapse, or if a failure of the roof would lead to a catastrophic collapse.

7. Proclaim a collapse zone.

Immediate safety precautions must be taken if factors indicate the potential for a building collapse. All persons operating inside the structure must be evacuated immediately and a collapse zone should be established around the perimeter. Once a collapse zone has been established, the area should be clearly marked and monitored, to make certain that no fire fighters enter the danger zone.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should establish and implement written standard operating procedures (SOPs) regarding emergency operations on the fireground.9,10

Discussion: SOPs are a set of organizational directives that establish a standard course of action on the fireground to increase the effectiveness of the fire fighting team. SOPs are characterized as being written and official. They are applied to all situations, enforced, and integrated into the management model. They generally include such areas as: basic command functions; communications and dispatching; fireground safety; guidelines that establish and describe tactical priorities and related support functions; method of initial resource deployment; and an outline of responsibilities and functions for various companies and units. Unwritten directives are difficult to learn, remember, and apply. One approach to establishing SOPs is to have officers and fire fighters decide how all operations will be conducted and then commit to those decisions in writing. The department in charge of this incident has SOPs but not specific and detailed procedures for fireground operations.

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should develop and coordinate pre-incident planning protocols throughout mutual aid departments.11

Discussion: NFPA 1620 provides guidance to assist departments in establishing pre-incident plans. Pre-incident planning that includes agreements formed by a coalition of all involved parties including mutual aid fire departments, EMS companies, and police, will present a coordinated response to emergency situations, and may save valuable time by a more rapid implementation of pre-determined protocols.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should implement joint training on response protocols throughout mutual aid departments.12

Discussion: Mutual aid companies should train together and not wait until an incident occurs to attempt to integrate the participating departments into a functional team. Differences in equipment and procedures need to be identified and resolved before an emergency where lives may be at stake. Procedures and protocols that are jointly developed, and have the support of the majority of participating departments, will greatly enhance overall safety and efficiency on the fireground. Once methods and procedures are agreed upon, training protocols must be developed and joint-training sessions conducted to relay appropriate information to all affected department members.

In this incident, a minimum of six volunteer fire departments were on the scene. Coordination of fireground efforts would have been enhanced if protocol planning and training had taken place among mutual aid departments.

Recommendation #6: Fire departments should ensure that an Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed and on-scene early in the fireground operation.2,13-15

Discussion: According to NFPA 1561, Sec. 4.1.1, the Incident Commander (IC) is responsible for the overall coordination and direction of all activities at an incident. This includes overall responsibility for the safety and health of all personnel and for other persons operating within the incident management system. Whereas the IC is in overall command at the scene, certain functions must be delegated to ensure that adequate scene management is accomplished. According to NFPA 1500, Sec. 6-1.3, “As incidents escalate in size and complexity, the Incident Commander shall divide the incident into tactical-level management units and assign an incident safety officer to assess the incident scene for hazards or potential hazards.” The incident safety officer (ISO) is defined as “an individual appointed to respond to, or assigned while at, an incident scene by the Incident Commander to perform the duties and responsibilities specified in this standard. This individual can be the health and safety officer or it can be a separate function.” NFPA 1521, Sec. 2-1.4.1 states that “an incident safety officer shall be appointed when activities, size, or need occurs.” Each of these guidelines complements the other and indicates that the IC is in overall command at the scene, but acknowledges that oversight of all operations is difficult. On-scene fire fighter health and safety is best preserved by delegating the function of safety and health oversight to the ISO.

Additionally, the IC relies upon fire fighters and the incident safety officer to relay feedback on fireground conditions in order to make timely, informed decisions regarding risk versus gain and offensive versus defensive operations. The safety of all personnel on the fireground is directly impacted by clear, concise, and timely communications among mutual aid fire departments, sector command, the ISO, and IC. In this incident, a designated safety officer could have assisted with continual size-up and timely communications regarding safety on the fireground.

REFERENCES

- Brunacini AV [1985]. Fire command. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association

- NFPA [1997]. NFPA 1500, standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Morris GP, Brunacini N, Whale L [1994]. Fireground accountability; the Phoenix system. Fire Engineering 147(4):45-61.

- International Fire Service Training Association [1993]. Fire service orientation and terminology. 3rd ed. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University.

- Dunn V [1988]. Collapse of burning buildings, a guide to fireground safety. Saddle Brook, NJ: PennWell.

- Dodson D [1999]. Fire department incident safety officer. New York: Delmar Publishers.

- NIOSH [1999]. Preventing injuries and deaths of fire fighters due to structural collapse. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 99-146.

- Fire Fighter’s Handbook [2000]. Essentials of fire fighting and emergency response. New York: Delmar Publishers.

- NFPA [1997]. Fire protection handbook. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- International Fire Service Training Association [1995]. Essentials of fire fighting. 3rd ed. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University.

- NFPA [1998]. NFPA 1620, standard on recommended practice for pre-incident planning. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Sealy CL [2003]. Multi-company training: Part 1. Firehouse, February 2003 Issue.

- NFPA [1995]. NFPA 1561: standard on fire department incident management system. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [1997]. NFPA 1521: standard on fire department safety officer. 1997 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- Foley SN, ed. [1998]. Fire department occupational health and safety standards handbook. 1st ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Jay Tarley, Virginia Lutz, and Stephen Berardinelli, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, NIOSH, Division of Safety Research, Surveillance and Field Investigation Branch.

Diagram 1. Incident scene aerial view

Diagram 2. Side view of fire building showing elevation

Photo 1. Rear Porch, Exposure D

This page was last updated on 11/20/03