Pumper Truck Rollover Claims the Life of a Volunteer Fire Fighter - Missouri

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty…A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2000-33 Date Released: November 22, 2000

SUMMARY

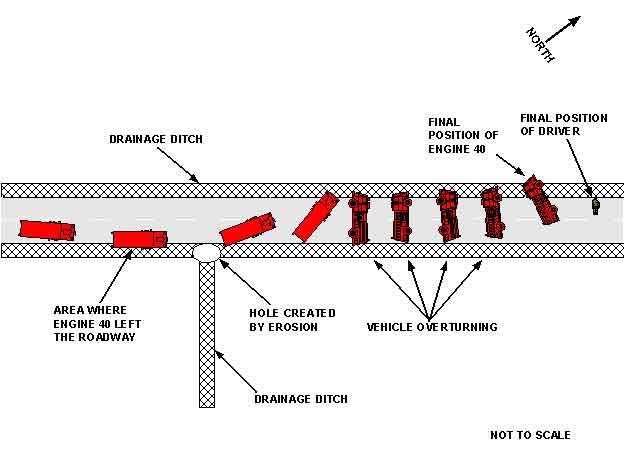

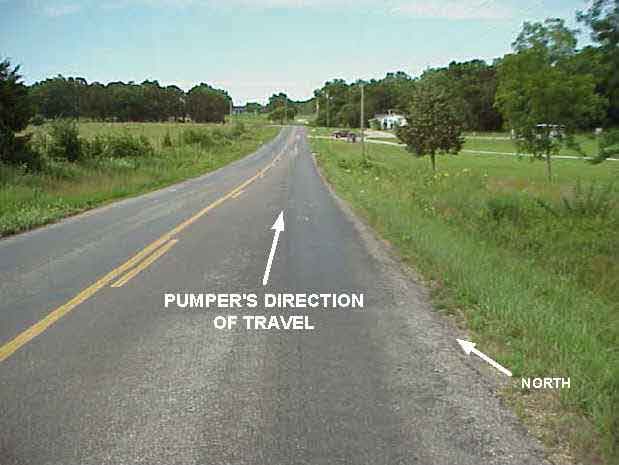

On May 27, 2000, a 27-year-old male volunteer fire fighter (the victim) died after losing control of the pumper truck (Engine 40) he was driving, which rolled approximately one and three-quarter revolutions and slid before coming to rest. At 1522 hours, the fire department was dispatched to a motor-vehicle incident, with unknown injuries. At 1523 hours, the victim responded in Engine 40. Also responding to the scene was a Captain in his privately owned vehicle (POV) and an Assistant Chief in a department vehicle. At 1539 hours, the victim radioed to Central Dispatch that the call was unfounded and he was returning to the station. En route to the station, the engine was traveling northbound on a two-lane state road with the Captain following behind (see Photo #1). The engine drifted off the roadway on the right (east) side and passed over a large hole created by erosion at the end of a drainage culvert. The victim lost control of the engine after he overcorrected and applied his brakes in an attempt to steer the engine back onto the road. The engine rotated counterclockwise, came back onto the roadway and overturned. The engine rolled approximately one and three-quarter revolutions as it continued to skid, traveling northbound (see Diagram). The victim was ejected from the engine and sustained fatal injuries as a result of the collision. The engine came to rest on its left side, facing west and blocking the southbound lane of the roadway. The cab area of the engine burst into flames as it sat at rest.

NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should

- ensure all drivers of fire department vehicles are responsible for the safe and prudent operation of the vehicle under all conditions

- enforce standard operating procedures (SOPs) on the use of seat belts in all emergency vehicles

- ensure all drivers of fire department vehicles receive driver training at least twice a year

Incident Site

INTRODUCTION

On May 27, 2000, a 27-year-old male volunteer fire fighter died from injuries sustained in a pumper truck rollover that occurred while returning from an unfounded motor-vehicle incident call. On May 30, 2000, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of this incident. On June 26-27, 2000, two Safety and Occupational Health Specialists investigated this incident. They conducted interviews with the Chief and members of the fire department involved in the incident, and with members of neighboring fire departments who had responded to provide mutual aid. They obtained copies of photos, police and crash reconstruction reports, and the death certificate. The victim’s training records and the department’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) were reviewed. The incident site and the truck were visited and photographed. The combination fire department involved in this incident had 6 fire stations and served a population of 30,000 in a geographical area of 283 square miles. The combination department is comprised of 1 career Fire Chief and 35 volunteer fire fighters. The engine involved in this incident was a 1987 Chevrolet C-70 truck with dual wheels on the rear axle. The pumper’s tank was manufactured with a 1,000-gallon water tank capacity. Because of repairs for a leaking tank several years prior to this incident, the capacity of the water tank was reduced to 900 gallons. At the time of the incident the water tank was full and equipped with baffles. The gross vehicle weight of the engine with 900 gallons of water is 31,000 lbs. There were no written maintenance records kept by the department for the engine. Weather conditions on the day of the incident were partly cloudy and the roadway was dry. Rain had occurred on the evening prior to the incident, so the earthen embankment was soft. The victim had a basic and current Class F driver’s license. The state does not require a commercial driver’s license for persons operating emergency vehicles or apparatus. The victim was not wearing his seat belt, however, the department did have a written policy which required the use of seat belts. The road on which the engine was traveling was a two-lane, asphalt state road, marked with a double solid-yellow center line and white fog lines. The road measured approximately 20 feet wide and there are no shoulders in the area of the collision. The road had a posted speed limit of 55 mph. The State of Missouri has no mandatory requirements to become a fire fighter. The victim had completed approximately 50 hours of various State fire and rescue training courses, and had completed a 12-hour emergency response driving course offered through the State in 1997. The department does have written qualifications to become a qualified driver. Prior to being eligible to be a driver for the department, a fire fighter must complete a 6-month probationary period. The requirements for driving the engine include taking a verbal quiz, having a practical evaluation on pump operations and filling, and demonstrating driving skills to a department officer. The required hours of drive time vary according to the type of apparatus. The engine required 1 hour of drive time with an department officer. At the time of the investigation, training records of instruction offered through the department were not maintained. The victim had 5 years experience with the department, 4½ of those years as a qualified driver.

INVESTIGATION

On May 27, 2000, at 1522 hours, the combination fire department was notified by Central Dispatch of a motor vehicle incident. The volunteer fire fighter (the victim) marked Engine 40 en route to the scene at 1523 hours. Responding from another station was a fire fighter in Squad 50. Additionally, responding to the incident from the victim’s department were an Assistant Chief in a department vehicle, a Captain, a Lieutenant, and approximately five other fire fighters, who responded in privately owned vehicles (POVs). At 1539 hours, the victim radioed to Central Dispatch that the call was unfounded and he was in service, and returning to the station. The engine was traveling northbound on a two-lane state road with a posted speed limit of 55 mph (see Photo #1). On the return trip the Assistant Chief noticed the engine following behind him, approximately a quarter of a mile back. After traveling approximately 1 mile the Assistant Chief lost sight of the engine. The engine was approximately 1 mile from the station at this time. The Captain’s vehicle followed the engine approximately 100 feet behind. During this time another emergency medical call was in progress. The Assistant Chief pulled over at the victim’s station and radioed back to the engine to discuss the emergency medical call. However, there was no response from the victim. According to the Captain, who witnessed the event, and from evidence collected by the state highway patrol and from the crash reconstruction report, for unknown reasons the engine drifted off the roadway on the right (east) side. Note: The highway patrol estimated that the right rear tires of the engine initially left the roadway while the vehicle was traveling approximately 45 mph. This estimated speed was based on the statement of the witness (the Captain), who was following the engine. There are no shoulders in this area of the road. The engine continued to travel along an earthen embankment off the side of the road. The victim attempted to bring the engine back onto the roadway, however, was unable to. Note: Rain had occurred on the evening prior to the incident, so the earthen embankment was soft. The right side of the tires traveled along the earthen embankment for approximately 164 feet. The engine continued to travel and passed over a large hole created by erosion at the end of a drainage culvert (see Diagram). Note: The large hole was estimated to be 8 feet in depth and 15 feet in width. The victim lost control of the engine when he overcorrected and applied his brakes in his attempt to steer the engine back to the roadway left (west) side. The engine rotated counterclockwise, and came back up unto the road and traveled across the roadway. The engine traveled across the road for approximately 18 feet before overturning. The engine rolled approximately one and three-quarter revolutions and slid as it continued northbound. The engine came to rest on the passenger side, partially off the roadway on the left (west) side of the roadway, blocking the southbound lane (see Photo #2). The victim was ejected from the engine, sustaining fatal injuries. Note: It remains undetermined as to where the victim exited the engine. The victim was wearing ordinary street clothes. The engine was equipped with a shoulder and lap seat belt safety restraint system for the driver and passenger positions. The highway patrol’s report indicated that the victim was not wearing his seat-belt safety restraint system at the time of the incident. The cab area of the engine burst into flames as it sat at rest. The Captain, who was following the engine, stopped approximately 50 feet back from the engine and radioed to Central Dispatch to report the incident and request assistance. Between 1550 hours and 1553 hours, the following were dispatched to the to the incident scene: two mutual aid fire departments, and an ambulance. The Chief from the department in the incident heard the radio dispatch and responded from his residence in his department vehicle. The Assistant Chief was approximately 1 mile away from the incident scene and heard the radio traffic and responded. At approximately a half-mile away from the scene the Assistant Chief could see smoke coming from the roadway. Once on the scene he observed the Captain looking for the victim near the engine. The Captain, Assistant Chief, and a fire fighter who responded in his POV, located the victim lying on his back approximately 10 feet from the engine. Note: The victim was lying with his head across the (west) white painted fog line. Because of the fire in the cab area, the Captain, Assistant Chief, and a fire fighter carried the victim approximately 30 to 40 feet away from the engine. They were unable to get a pulse from the victim, and could see that he had a massive head injury. Monitoring radio traffic but not dispatched, Tanker 4 from the victim’s department responded to the scene with a driver and a fire fighter. Tanker 4 arrived on the scene, and with the help of other fire fighters who had responded by POV, put the fire out in the cab area of the engine (see Photo #3). Note: The fire is believed to have originated from fuel leaking from the cap vent on the full fuel tank. The fuel spread under the passenger side door and is believed to have been ignited from sparks when the engine was rolling and sliding on the roadway. Once on the scene, the Chief from the department involved in the incident assumed the role of the Incident Commander (IC). At 1601 hours, the ambulance arrived on the scene with an emergency medical technician (EMT) and a paramedic. Ambulance personnel did an assessment of the victim and placed a heart monitor on him. The monitor indicated light electrical activity of the heart. The ambulance personnel initiated Basic Life Support activities on the victim with the help of other fire fighters on the scene. At approximately 1608 hours, the ambulance personnel requested that the victim be transported to the hospital by helicopter. A Chief from one of the mutual aid departments arrived on scene in his POV and took over the role of IC. The IC made assignments for the on-scene fire fighters to provide traffic control and assist with set up for the landing of the helicopter. At 1626 hours, the helicopter landed in a field approximately 100 yards away from the scene. After performing a patient assessment on the victim, the flight nurse from the helicopter made a call to an area medical center. Due to the victim’s condition, the medical director gave orders to discontinue life supporting activities and not to transport the victim in the helicopter. He was pronounced dead by the flight crew and was removed by the Coroner.

CAUSE OF DEATH

The death certificate lists the cause of death as cerebral laceration, due to an open skull fracture.

RECOMMENDATIONS/DISCUSSION

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure all drivers of fire department vehicles are responsible for the safe and prudent operation of the vehicle under all conditions.1

Discussion: Fire departments should ensure drivers of fire service vehicles are familiar with the potential hazards/conditions that exist on the roadways (e.g., insufficient shoulder) on which they may be traveling. In this incident, the speed of the engine when it left the roadway was estimated to be under the posted 55 mph speed limit, however, for unknown reasons the engine drifted off the roadway. The potential motor vehicle hazards that existed on the roadway of this incident included (1) the earthen embankment being soft, (2) no shoulders, and (3) a large hole that was created by erosion at the end of a drainage culvert.

Recommendation #2: Fire departments should enforce standard operating procedures (SOPs) on the use of seat belts in all emergency vehicles.2

Discussion: Fire departments should enforce SOPs on the use of seat belts. The SOPs should apply to all persons riding in all emergency vehicles and state that all persons should be seated and secured in an approved riding position anytime the vehicle is in motion. The department did have written SOPs addressing emergency and non-emergency response driving, which required that seat belts be worn at all times.

Recommendation #3: Fire departments should ensure all drivers of fire department vehicles receive driver training at least twice a year.3,4

Discussion: Driver training should be provided to all driver/operators as often as necessary to meet the requirements of NFPA 1451, but not less than twice a year. This training should be documented and cover defensive driving techniques during emergency and non-emergency conditions. The department did have written requirements to become a certified driver, however, did not retain any type of documentation to reflect the training offered through the department. The department required drivers to receive driver certification training only one time during their tenure with the department. Additionally, fire departments’ driver training should be in accordance with NFPA 1451, Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program and NFPA 1002, Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications. These standards state that departments should establish and maintain a driver training education program and each member should be provided driver training not less than twice a year. During this training, each driver should operate the vehicle and perform tasks that the driver/operator is expected to encounter during normal operations, to ensure the vehicle is safely operated in compliance with all applicable state and local laws.

REFERENCES

1. National Fire Protection Association [1997]. NFPA 1500, Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

2. Cook, John Lee Jr. [1998]. Standard operating procedures and guidelines. Saddle Brook, NJ: Penn Well.

3. National Fire Protection Association [1997]. NFPA 1451, Standard for a fire service vehicle operations training program. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

4. National Fire Protection Association [1993]. NFPA 1002, Standard for a fire department vehicle driver/operator professional qualifications. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

INVESTIGATOR INFORMATION

This incident was investigated by Nancy T. Romano and Kimberly L. Cortez, Safety and Occupational Health Specialists, Division of Safety Research, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch NIOSH.

Diagram. Aerial View of Incident Site; diagram indicates the locations of the two drainage ditches, the

hole created by erosion, the final position of the driver, and the various positions of Engine 40 including

the approximate location of where it left the roadway, where it overturned, and its final position.

Photo 1. View of Road Traveling Northbound Where Pumper Truck Veered Off Road and Rolled Over

Photo 2. Photograph showing a close-up view of Engine 40 shortly after the incident occurred;

photograph shows the top of the engine, lying on the driver’s side.

Photo 3. Pumper Truck Involved in This Incident

This page was last updated on 11/21/05