Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) is an immunologically-mediated sequela of pharyngitis or skin infections caused by nephritogenic strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. S. pyogenes are also called group A Streptococcus (group A strep).

Etiology

PSGN is usually an immunologically-mediated, nonsuppurative, delayed sequela of pharyngitis or skin infections caused by nephritogenic strains of S. pyogenes. Reported outbreaks of PSGN caused by group C streptococci are rare. 1,2

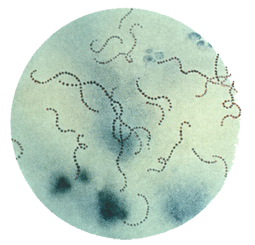

S. pyogenes are gram-positive cocci that grow in chains (see Figure 1). They exhibit β-hemolysis (complete hemolysis) when grown on blood agar plates. They belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system for β-hemolytic Streptococcus, and thus are called group A streptococci.1

Clinical features

The clinical features of acute glomerulonephritis include:

- Edema (often pronounced facial and orbital edema, especially on arising in the morning)

- Hypertension

- Proteinuria

- Macroscopic hematuria, with urine appearing dark, reddish-brown

- Complaints of lethargy, generalized weakness, or anorexia

Figure 1. Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus) on Gram stain. Source: Public Health Image Library, CDC

Laboratory examination usually reveals:

- Mild normocytic normochromic anemia

- Slight hypoproteinemia

- Elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Low total hemolytic complement and C3 complement

Patients usually have decreased urine output. Urine examination often reveals protein (usually <3 grams per day) and hemoglobin with red blood cell casts.

Additionally, some evidence from epidemic situations indicates that subclinical cases of PSGN may occur. Thus, some individuals may have symptoms that are mild enough to not come to medical attention.1

Transmission

As a delayed sequela of group A strep infection, PSGN is not contagious. However, people mostly commonly spread group A strep through direct person-to-person transmission. Typically, transmission occurs through saliva or nasal secretions from an infected person. Symptomatic people are much more likely to transmit the bacteria than asymptomatic carriers. Crowded conditions — such as those in schools, daycare centers, or military training facilities — facilitate transmission. Although rare, spread of group A strep infections may also occur via food. Foodborne outbreaks of pharyngitis have occurred due to improper food handling. Environmental transmission via surfaces and fomites was historically not thought to occur. However, evidence from outbreak investigations indicate that environmental transmission of GAS may be possible, although it is likely a less common route of transmission.

Humans are the primary reservoir for group A strep. There is no evidence to indicate that pets can transmit the bacteria to humans.

Incubation period

PSGN occurs after a latent period of approximately 10 days following group A strep pharyngitis. Generally, PSGN occurs up to 3 weeks following group A strep skin infections.1

Risk factors

The risk factors for PSGN are the same as for the preceding group A strep pharyngitis or skin infection. PSGN is more common in children, although it can occur in adults. Pharyngitis-associated PSGN is most common among children of early school age. Pyoderma-associated PSGN is most common among children of pre-school age.

There are no known risk factors specific for PSGN. However, the risk of PSGN is increased if a nephritogenic strain of group A strep is introduced into a household.

Diagnosis and testing

The differential diagnosis of PSGN includes other infectious and non-infectious causes of acute glomerulonephritis. Clinical history and findings with evidence of a preceding group A strep infection should inform a PSGN diagnosis. Evidence of preceding group A strep infection can include1

- Isolation of group A strep from the throat

- Isolation of group A strep from skin lesions

- Elevated streptococcal antibodies

Treatment

Treatment of PSGN focuses on managing hypertension and edema. Additionally, patients should receive penicillin (preferably penicillin G benzathine) to eradicate the nephritogenic strain. This will prevent spread of the strain to other people.1

Prognosis and complications

The prognosis of PSGN in children is very good; more than 90% of children make a full recovery. Adults with PSGN are more likely to have a worse outcome due to residual renal function impairment.1

Prevention

There is insufficient evidence to determine if antimicrobial therapy can prevent PSGN.1,2 Thus, it is important to prevent the primary group A streptococcal skin or pharyngeal infection. However, treating PSGN patients with antibiotics can stop a nephritogenic strain from circulating in a household. Thus, treating PSGN patients can prevent additional infections among close contacts.

Good hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette can reduce the spread of all types of group A strep infection. Hand hygiene is especially important after coughing and sneezing and before preparing foods or eating. Good respiratory etiquette involves covering your cough or sneeze. Treating an infected person with an antibiotic for 12 hours or longer limits their ability to transmit the bacteria. Thus, people with group A strep pharyngitis or scarlet fever should stay home from work, school, or daycare until:

- They are afebrile

AND - At least 12-24 hours after starting appropriate antibiotic therapy*

Epidemiology

Humans are the only reservoir for group A strep. One 1960s study found a 10% to 15% attack rate of PSGN following throat or skin infection with a nephritogenic strain of group A strep.5 An estimated 470,000 cases of PSGN and 5,000 deaths from PSGN occur each year globally.3

Footnote

Per the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book 2021–2024, children with group A strep pharyngitis should not return to school or a childcare setting until well appearing and at least 12 hours after beginning appropriate antibiotic therapy. In certain scenarios, such as an infection in a healthcare worker or in a group A strep outbreak setting, staying home for at least 24 hours after beginning appropriate antibiotics should be considered.

- Sainato RJ, Weisse ME. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and antibiotics: A fresh look at old data. Clin Ped. 2019;58(1):10–12.

- Bateman E, Mansour S, Okafor E, Arrington K, Hong B, Cervantes J. Examining the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy in preventing the development of postinfectious glomerulonephritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Rep. 2022;14(2):176–83.

- Carapetis JR. The current evidence for the burden of group A streptococcal diseases. World Health Organization. Geneva. 2005.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. Group A streptococcal infections. In Kimberlin DW, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH, editors. 32nd ed. Red Book: 2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village (IL). American Academy of Pediatrics. 2021;633–46.

- Anthony BF, Kaplan EL, Wannamaker LW, Briese FW, Chapman SS. Attack rates of acute nephritis after Type 49 streptococcal infection of the skin and of the respiratory tract. J Clin Invest. 1969;48(9):1679–704.