Impetigo

Impetigo (also called pyoderma) is a superficial bacterial skin infection that is highly contagious. Impetigo can be caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. This page focuses on infections caused by S. pyogenes, which are also called group A Streptococcus (group A strep).

Etiology

Impetigo can be bullous or non-bullous. Toxin-producing S. aureus cause bullous impetigo. S. aureus, S. pyogenes, or both cause non-bullous impetigo, which is also called “impetigo contagiosa.”

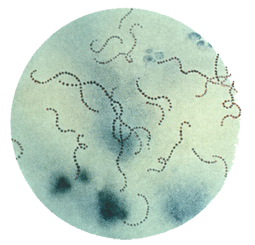

S. pyogenes are gram-positive cocci that grow in chains (see Figure 1). They exhibit β-hemolysis (complete hemolysis) when grown on blood agar plates. They belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system for β-hemolytic Streptococcus, and thus are also called group A streptococci.

Clinical features

Streptococcal impetigo, or non-bullous impetigo, begins as papules. The papules evolve to pustules and then break down to form thick, adherent crusty lesions (Figure 2). The crusts are typically golden or “honey-colored.” These lesions usually appear on exposed areas of the body, most commonly the face and extremities, but can occur anywhere on the body. Multiple lesions typically develop. In cases of non-bullous impetigo, physical examination cannot differentiate streptococcal from staphylococcal infection.1

Figure 1. Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus) on Gram stain. Source: Public Health Image Library, CDC

Transmission

Streptococcal impetigo is most commonly spread through direct contact with other people with impetigo, including through contact with drainage from impetigo lesions. Lesions can be spread (by fingers and clothing) to other parts of the body. People with impetigo are much more likely to transmit the bacteria than asymptomatic carriers. Crowding, such as found in schools and daycare centers, increases the risk of disease spread from person to person.

Humans are the primary reservoir for group A strep. There is no evidence to indicate that pets can transmit the bacteria to humans.

Incubation period

The incubation period of impetigo, from colonization of the skin to development of the characteristic lesions, is about 10 days.1 It is important to note not everyone who becomes colonized will go on to develop impetigo.

Figure 2. Streptococcus pyogenes caused the lesions on this patient’s left forearm. Source: Public Health Image Library, CDC

Risk factors

Impetigo can occur in people of all ages, but it is most common among children 2 through 5 years of age. Scabies infections and activities that result in cutaneous cuts or abrasions increase the risk of impetigo. Poor personal hygiene, including lack of proper hand, face, or body hygiene, can increase someone’s risk of impetigo. Impetigo can occur in any climate and at any time of year, but is more common during the summer in temperate climates and in tropical or subtropical locations.1

Diagnosis and testing

Impetigo is diagnosed by physical examination, but physical examination cannot reliably differentiate between streptococcal and staphylococcal non-bullous impetigo.1 Gram stain or culture of the exudate or pus from an impetigo lesion can identify the bacterial cause; however, laboratory testing is not necessary nor routinely performed in clinical practice.

Treatment

Antibiotic treatment, whether oral or topical, should be aimed at both group A strep and S. aureus. Topical antibiotics, mupirocin or retapamulin, may be used when there are only a few lesions, while oral antibiotics are used for multiple lesions.1,2,3

Prognosis and complications

Rarely, complications can occur after impetigo. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) can occur as a delayed non-suppurative complication of impetigo. It most often occurs one to two weeks after the original infection resolves. PSGN is thought to be the result of an immune response that is triggered by the group A strep infection. Historically, acute rheumatic fever was not thought to occur following group A strep skin infections. However, new evidence suggests that acute rheumatic fever can occur as a complication after group A strep skin infections, including impetigo.

Prevention

The spread of impetigo can be prevented by covering lesions, treating with antibiotics, and practicing good face, body, and hand hygiene. Clothing, linens, and towels used by an infected person should be washed every day and not shared with others in the household. Persons with impetigo can return to school or work after initiating antibiotic treatment as long as lesions are covered.

The spread of all types of group A strep infection can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing and before preparing foods or eating, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze).

Epidemiology

In the United States, impetigo is more common in the summer.1 The World Health Organization estimates that 111 million children in less developed countries have streptococcal impetigo at any one time.4 Higher rates of impetigo are found in crowded and impoverished settings, in warm and humid conditions, and among populations with poor hygiene.

- Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Streptococcus pyogenes. In Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M, editors. 8th Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2015:2:2285–300.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. Group A streptococcal infections. In Kimberlin DW, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH, editors. 32nd ed. Red Book: 2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:633–46.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147–59.

- Carapetis JR. The current evidence for the burden of group A streptococcal diseases. World Health Organization. Geneva. 2005.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Infection control in healthcare personnel: Epidemiology and control of selected infections transmitted among healthcare personnel and patients.