Information for Healthcare Providers

Scrub Typhus

Scrub typhus is distributed throughout the Asia-Pacific region. It is endemic to Korea, China, Taiwan, Japan, Pakistan, India, Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Australia. In 1999, the World Health Organization listed scrub typhus as one of the most underdiagnosed and underreported causes of febrile illness in the Asian region.

Scrub typhus is transmitted to humans through bites from infected larval trombiculid mites, commonly known as chiggers. The following species are known vectors of scrub typhus: Leptotrombidium pallidum, L. fuji, L. scutellare, and L. akamushi. Seasonality of the disease is determined by the appearance of larvae. In temperate zones, scrub typhus season is observed mainly in the fall, but also occurs in the spring. If a person is bitten by an infected mite, disease occurs within 7–10 days and typically lasts 14–21 days without appropriate treatment.

The majority of cases of scrub typhus occur in rural areas where mite-harboring vegetation is common. Interestingly, studies have described focal areas of scrub vegetation as small as a few square meters that are infested with these mites. If people enter one of these hot spots, their risk of disease increases dramatically.

Clinical Characteristics

Symptoms of scrub typhus begin abruptly, 7 or more days after exposure. Scrub typhus causes an acute febrile illness that can range from mild and self-limiting to severe or even deadly. Typical signs and symptoms include:

- Fever and chills

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Eschar

- Altered mental status, ranging from confusion to coma or delirium

- Lymphadenopathy

- Rash

Most patients have thrombocytopenia and may also show elevated levels of liver enzymes, bilirubin, or creatinine. Enlargement of the spleen and liver may be observed. Severe manifestations usually develop after the first week of untreated illness and may include multiple organ dysfunction syndrome with hemorrhaging, acute respiratory distress syndrome, encephalitis, pneumonia, renal or liver failure, and even death. During pregnancy, scrub typhus frequently leads to spontaneous abortion. Relapses may occur following apparent recovery in cases where inadequate treatment has occurred. Relapse is usually less severe than the initial presentation.

Eschar

The area around the bite may develop a necrotic skin lesion known as an eschar pdf icon[PDF – 2 pages]. The eschar may appear before the individual begins to develop systemic symptoms. Common sites of an eschar are axilla, under the breast, and groin, and less often on the abdomen, back, and extremities. Multiple eschars have been reported.

Rash

About 25–50% of scrub typhus patients develop a rash. The rash is usually macular or maculopapular. Typically, it will begin on the abdomen of an infected individual and then spread to the extremities. Petechiae are uncommon.

Physician Diagnosis

It is important to treat scrub typhus early in the course of the disease in order to avert life-threatening complications. A reliable diagnostic laboratory test in the early phase of illness is not currently available; therefore, diagnosis is based on clinical findings and epidemiologic setting. Treatment should never be withheld pending diagnostic tests.

Laboratory Confirmation

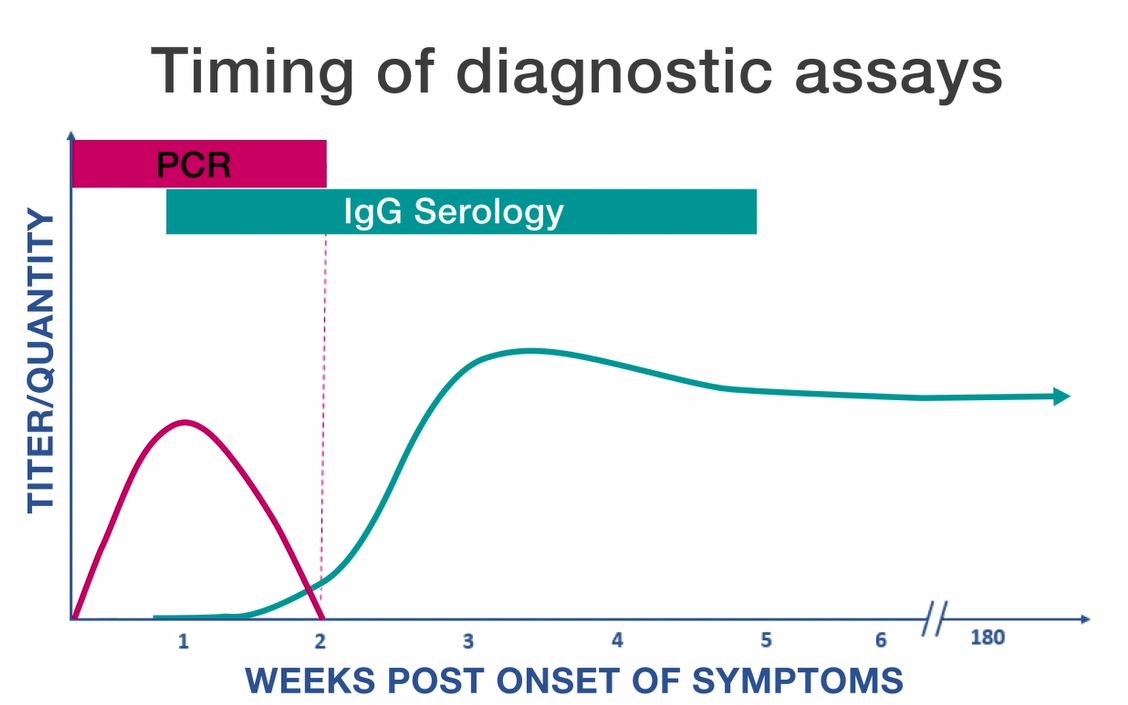

Serologic assays are the most frequently used methods for confirming cases of scrub typhus. The indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is generally considered the reference standard, but is usually not available in developing countries where this disease is endemic. Other serological tests include ELISA and indirect immunuoperoxidase (IIP) assays. Weil-Felix OX-K agglutination assays may be used in some international settings but lack sensitivity and specificity and are not generally used in the United States. These assays can detect either IgG or IgM antibodies. Diagnosis is typically confirmed by documenting a four-fold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent samples. Acute specimens are taken during the first week of illness and convalescent samples are taken 2–4 weeks later. IgG antibodies are considered more accurate than IgM, but detectable levels of IgG antibody generally do not appear until 7–10 days after the onset of illness.

Because antibody titers may persist in some individuals for years after the original exposure, only demonstration of recent changes in titers between paired specimens can be considered reliable confirmation of an acute scrub typhus infection. The most rapid and specific diagnostic assays for scrub typhus rely on molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which can detect DNA in a whole blood, eschar swab pdf icon[PDF – 1 page], or tissue sample. Immunostaining procedures can also be performed on formalin-fixed tissue samples. Since scrub typhus is not common in the United States, confirmatory tests are not typically available at state and local health departments; nonetheless, IFA, culture, and PCR assays can all be performed at the CDC through submission from state health departments.

Treatment

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for suspected scrub typhus in persons of all ages. Recommended dosages of doxycycline:

- Adults: 100 mg twice per day

- Children under 45 kg (100 lbs): 2.2 mg/kg body weight twice per day

Treatment alternatives primarily for patients with severe doxycycline allergy or women who are pregnant include azithromycin, chloramphenicol, or rifampin. Patients should be treated for at least 3 days after the fever subsides and until there is evidence of clinical improvement. Single-dose or short courses of doxycycline may lead to a relapse in illness.

Murine Typhus

Murine typhus is a flea-borne illness caused by the bacterium Rickettsia typhi. Murine typhus occurs worldwide, primarily in tropical and subtropical climates where rats (the primary animal reservoir) and rat fleas are present. People become infected with R. typhi when they come into contact with infected flea feces via scratched or abraded skin. Exposure can also occur when mucous membranes are exposed to infected feces or when a patient inhales the feces. Due to the murine typhus enzootic cycle, human infections often occur in areas where humans and host animals come into regular contact, including areas of low sanitation where rats are abundant. Most cases are reported from spring to early fall.

Several flea species have been identified as potential vectors for murine typhus, including the rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), and mouse flea (Leptopsyllia segnis). Opossums, dogs, and cats living in urban or suburban areas have also been implicated as host species for fleas carrying R. typhi in recent cases in the United States and Spain.

In the United States, most cases of murine typhus occur in Texas, California, and Hawaii.

Clinical Characteristics

Symptoms usually begin 7–14 days following exposure. Patients typically present with fever and headache or fever and rash and may also experience:

- Myalgia

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Cough

- Altered mental status

Common laboratory findings may include anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, hyponatremia, and elevated levels of liver enzymes. While the majority of patients experience a self-limited illness, severe and fatal cases have been reported with pulmonary and neurologic manifestations.

Rash

The rash typically occurs at the end of the first week of the illness and lasts 1–4 days. It generally starts as a maculopapular eruption on the trunk and spreads peripherally, sparing the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Rash may vary among individuals, or may be absent altogether and should not be relied upon for diagnosis.

Physician Diagnosis

Due to the non-specific presentation of murine typhus and the unreliability of early diagnostic tests, treatment decisions should be made based on clinical presentation and epidemiologic settings. Murine typhus should be considered in patients with persistent fever, a history of exposure to fleas or flea hosts (such as rats, cats or opossums), or if there is a history of travel to tropical or semitropical regions. When treated early, patients typically experience a less severe illness and shorter recovery time. Treatment should never be withheld pending diagnostic tests. Clusters of murine typhus have been reported in the United States, and suspected cases should be reported to the state or local health department to prevent further exposures.

Laboratory Confirmation

Rickettsia typhi can be detected via indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay, immunohistochemistry (IHC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays using blood, plasma, or tissue samples, or culture isolation. PCR is most sensitive on samples taken during the first week of illness, but prior to the start of doxycycline.

Serologic tests (typically using IFA) are the most common means of confirming murine typhus and can be used to detect either IgG or IgM antibodies. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by demonstrating a four-fold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent samples. Acute specimens are taken during the first week of illness and convalescent samples are taken 2–4 weeks later. IgG antibodies are considered more accurate than IgM. Detectable levels of IgG antibody generally do not appear until 7–10 days after the onset of illness.

Because antibody titers may persist in some individuals for years after the original exposure, only demonstration of recent changes in titers between paired specimens can be considered reliable serological confirmation of an acute murine typhus infection. R. typhi antigens frequently cross-react with those of R. prowazekii and R. felis, and less often with R. rickettsii. When possible, species-specific assays for R. typhi, R. prowazekii, R. felis, and R. rickettsii should be run in parallel. IHC can be used to detect infection with typhus group Rickettsia (including R. prowazekii and R. typhi) in formalin-fixed tissue samples. PCR of whole blood or tissue can distinguish between infection with R. typhi and R. prowazekii although the sensitivity of these assays varies considerably based on the sample type, timing of sample collection, and the severity of disease.

Treatment

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for suspected cases of murine typhus in adults and children of all ages. Recommended dosages of doxycycline:

- Adults: 100 mg twice per day

- Children under 45 kg (100 lbs.): 2.2 mg/kg body weight given twice a day

Patients should be treated for at least 3 days after the fever subsides and until there is evidence of clinical improvement (usually 7–10 days).

To learn more, see Clinical FAQ

Epidemic Typhus

Outbreaks of epidemic typhus are most often associated with the clustering of large populations in unhygienic circumstances such as those resulting from war or famine, or occurring in refugee camps, prisons, and homeless populations. However, isolated cases have also reported in recent years outside of such settings.

The primary vector of epidemic typhus is Pediculus humanus corporis (human body louse). People become infected with R. prowazekii when they come into contact with the feces or crushed bodies of infected lice via cut or injured skin. Inhalational exposure of dried louse feces may also occur. R. prowazekii can remain infective in louse feces for up to 100 days. Body lice can proliferate to large numbers and rapidly transmit disease among crowded human populations by hiding out in clothes, blankets, or bedding.

In the United States, cases of epidemic typhus have been associated with exposure to flying squirrels or their nests. Fleas and lice carried by the squirrels become naturally infected with R. prowazekii; however, the exact mechanism of transmission remains unknown.

Clinical Characteristics

Signs and symptoms of epidemic typhus usually appear abruptly, 8–16 days following exposure to infected lice. Illness can vary from mild to severe, and even life-threatening. Symptoms of acute R. prowazekii infection are generally non-specific and include:

- Fever and chills

- Headache

- Rapid breathing

- Myalgia

- Rash

- Cough

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Altered mental status

Delay in treatment may result in advanced disease, including neurologic manifestations such as confusion, seizures, or coma, and widespread vasculitis (damage to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels). Laboratory abnormalities of acute infection may include jaundice, elevated liver enzyme levels, and thrombocytopenia. Some patients may remain infected without symptoms for many years following the initial illness. Flying squirrel-associated typhus cases are generally less severe, and no fatal cases have been reported.

Rash

The rash usually begins a couple of days after the onset of symptoms. It typically begins as a maculopapular eruption on the trunk of the body and spreads to the extremities, usually sparing the palms of hands and soles of feet. When the disease is severe, petechiae may develop. The rash may be variable among individuals and stage of infection, or may be absent altogether and should not be relied upon for diagnosis.

Brill-Zinsser Disease

Recrudescent infection with R. prowazekii, called Brill-Zinsser disease, may occur months or years after the initial illness, during times of extreme stress or when the immune system becomes weakened. The signs and symptoms of Brill-Zinsser disease are similar to the primary infection, with a rapid onset of chills, fever, headache, and malaise; however, Brill-Zinsser disease is generally milder and is rarely fatal. Patients with Brill-Zinsser disease harbor active R. prowazekii and, therefore, may pose a risk for reintroduction of the organism and new outbreaks.

Physician Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings and epidemiologic factors as reliable, early diagnostic tests are not available. Epidemic typhus should be considered in patients with persistent fever, a history of body louse exposure in crowded or unhygienic areas, or persons who may have come in contact with flying squirrels or their nests. When treated early, patients may experience a less severe illness and shorter recovery time. Treatment should never be withheld pending diagnostic tests. Epidemic typhus has the potential to spread rapidly among persons living in close quarters, so precautions should be taken to rapidly identify and treat patients and to eliminate body louse infestations.

Laboratory Confirmation

Rickettsia prowazekii can be detected via indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay, immunohistochemistry (IHC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of blood, plasma, or tissue samples, or culture isolation. Serologic tests are the most common means of confirmation and can be used to detect either IgG or IgM antibodies. Diagnosis is typically confirmed by documenting a four-fold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent samples. Acute specimens are taken during the first week of illness and convalescent samples are taken 2–4 weeks later. Detectable levels of IgG or IgM antibodies generally do not appear until 7–10 days after the onset of illness.

Because IgG antibody titers may persist in some individuals for years after the original exposure, only demonstration of recent changes in titers between paired specimens can be considered reliable serological confirmation of an acute epidemic typhus infection. R. prowazekii antigens may cross react with those of R. typhi, and occasionally with R. rickettsii. When possible, species-specific serological assays for R. prowazekii, R. typhi, and R. rickettsii should be run in parallel. Persons with Brill-Zinsser disease generally show a rise in IgG but not IgM antibodies to R. prowazekii. IHC can be used to detect infection with typhus group Rickettsia (including R. prowazekii and R. typhi) in formalin-fixed tissue samples. PCR of whole blood or tissue can distinguish between infection with R. typhi and R. prowazekii although the sensitivity of these assays vary considerably based on the sample type, timing of sample collection, and the severity of disease. Since epidemic typhus is not common in the United States, testing is not typically available at state and local health departments. IFA, culture, and PCR can all be performed at the CDC, through submission from state health departments.

Treatment

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for suspected cases of acute epidemic typhus and Brill-Zinsser disease in adults and children of all ages. Recommended dosages of doxycycline:

- Adults: 100 mg twice per day

- Children under 45 kg (100 lbs.): 2.2 mg/kg body weight given twice a day

Patients should be treated for at least 3 days after the fever subsides and until there is evidence of clinical improvement (usually 7–10 days).

Studies have shown that even a single 200 mg dose of doxycycline for adults has been reported as effective in halting outbreaks of epidemic typhus, although some patients may relapse if not treated for the full 7–10 days. There is no information about the efficacy of antibiotic therapy in the prevention of Brill-Zinsser disease. Patients with body louse infestations should be treated with delousing gels or creams (pediculicide).

Rickettsial Disease Diagnostic Testing and Interpretation

Rickettsial Disease Diagnostic Testing and Interpretation for Healthcare Providers

This video provides information on rickettsial disease diagnostic methods for healthcare providers, including what tests are available and when it is most appropriate to collect samples. This video focuses on the use of polymerase chain reaction (or PCR) tests, and the indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for rickettsial disease diagnosis.

Video download linkmedia icon

Access the Fact Sheet pdf icon[PDF – 1 page]