Clinical Manifestation

Presentation and First Evaluation

Patients with HPS typically present in a very nonspecific way with a relatively short febrile prodrome lasting 3-5 days. In addition to fever and myalgias, early symptoms include headache, chills, dizziness, non-productive cough, nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Malaise, diarrhea, and lightheadedness are reported by approximately half of all patients, with less frequent reports of arthralgias, back pain, and abdominal pain. Patients may report shortness of breath, (respiratory rate usually 26 – 30 times per minute). Typical findings on initial presentation include fever, tachypnea and tachycardia. The physical examination is usually otherwise normal.

HPS Clinical Presentation

Most frequent

- fever

- chills

- myalgias

Frequent

- headaches

- nausea, vomiting

- abdominal pain

- diarrhea

- cough

- malaise

Other

- shortness of breath

- dizziness

- arthralgia

- back or chest pain

- sweats

The diagnosis is seldom made at this stage, as cough and tachypnea generally do not develop until approximately day seven. Once the cardiopulmonary phase begins, however, the disease progresses rapidly, necessitating hospitalization and often ventilation within 24 hours.

Signs that make a diagnosis of HPS unlikely include rashes, conjunctival or other hemorrhages, throat or conjunctival erythema, petechiae, and peripheral or periorbital edema.

Clinical Assessment

If a hantavirus infection is suspected, a CBC and blood chemistry should be repeated every 8 to 12 hours.

A fall in the serum albumin and a rise in the hematocrit may indicate a fluid shift from the patient’s circulation into the lungs. The white blood cell count tends to be raised with a marked left shift. The percentage of white blood cells precursors may be as high as 50% and atypical lymphocytes are frequently present, usually at the time of onset of pulmonary edema.

In about 80% of individuals with HPS, the platelet count is below 150,000 units. A dramatic fall in the platelet count may herald a transition from the prodrome to the pulmonary edema phase of the illness.

The most severe cases of HPS develop disseminated intravenous coagulation (DIC), but, unlike the hantavirus-related hemorrhagic fevers (HFRS) seen in Asia, this is uncommon.

Coagulation Abnormalities in HPS

| Diagnostic Test | Day 1 | Day 2 |

|---|---|---|

| PT | 13.5 (NL) | 29.8 (up) |

| PTT | 32.8 (NL) | >240 (up) |

| Fibrinogen | N/A | 144 (down) |

| Fibrin Split Products | N/A | >4000 (up) |

Proteinuria, and mild elevations of transaminases, CPK, amylase, and creatinine have also been reported.

When metabolic acidosis, prolongation of PT and PPT times and rising serum lactate levels develop, the prognosis is poor. Marked renal insufficiency has mainly been noted among cases from the southeastern United States although some degree of renal insufficiency, assessed by elevated serum creatinine levels, has been noted in 15% of all patients.

The combination of atypical lymphocytes, a significant bandemia, and thrombocytopenia in the setting of pulmonary edema is strongly suggestive of a hantavirus infection.

Disease Development

Within 24 hours of initial evaluation, most patients develop some degree of hypotension and progressive evidence of pulmonary edema and hypoxia, usually requiring mechanical ventilation. The patients with fatal infections appear to have severe myocardial depression which can progress to sinus bradycardia with subsequent electromechanical dissociation, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation.

Hemodynamic compromise occurs a median of 5 days after symptom onset – usually dramatically within the first day of hospitalization. In contrast to HFRS, overt hemorrhage occurs rarely in HPS, although hemorrhage is occasionally seen in association with disseminated intravascular coagulation. In contrast to septic shock, HPS patients have a low cardiac output with a raised systemic vascular resistance. Poor prognostic indicators include a plasma lactate of greater than 4.0 mmol/L or a cardiac index of less than 2.2 L/min/m2 Whilst pulmonary edema and pleural effusions are common, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome is rarely seen. However, HPS patients sometimes have mildly impaired renal function. Survivors frequently become polyuric during convalescence and improve almost as rapidly as they decompensated.

Differential Diagnosis

The prodromal phase of HPS is indistinguishable clinically from numerous other viral infections. Often the only guide to the etiology of the patient’s illness is the blood picture, which may show circulating immunoblasts, which appear as large atypical lymphocytes, and thrombocytopenia. However, unlike other viral infections, HPS patients usually have concurrent left-shifted neutrophilia with circulating myelocytes.

In the cardiopulmonary stage of the disease, the patients have a diffuse pulmonary edema. The most frequent cause for such a picture is silent myocardial infarction so it is important to obtain an ECG and echocardiogram early to aid in the assessment. Intensivists at the University of New Mexico, where many of the patients have been managed, have found that a echocardiogram also helps to distinguish these patients from patients with ARDS as cardiac function is depressed to a much greater degree in the HPS patients and cardiac output does not respond to fluid challenge as it tends to with ARDS.

Infections in the immunocompetent which might present with a non-specific prodrome leading to acute cardiopulmonary deterioration as in HPS include leptospirosis, Legionnaire’s disease, mycoplasma, Q fever, chlamydia, and in regions where the organisms are present, septicemic plague, tularemia, coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. Non-infectious conditions such as Goodpasture’s syndrome should also be considered. Lack of coryza aids the clinical distinction between HPS and Influenza A infection.

It must be remembered that HPS is relatively uncommon and in the immunocompromised PCP, CMV, cryptococcus, aspergillus and graft vs. host disease are far more likely to be the cause of diffuse pulmonary infiltrates than a hantaviral infection.

Atypical Presentations

Atypical clinical presentations with prominent renal insufficiency have also been reported; therefore, HPS and infection due to Seoul virus, one of the Old World hantaviruses that cause HFRS, should be considered for patients with unexplained febrile nephropathies and appropriate laboratory findings. Asymptomatic illness is rare. However, an increasing number of acutely infected patients who develop either no cardiopulmonary disease or extremely mild pulmonary disease with minimal hypotension has been identified; one such patient was managed successfully as an outpatient.

Radiologic Findings

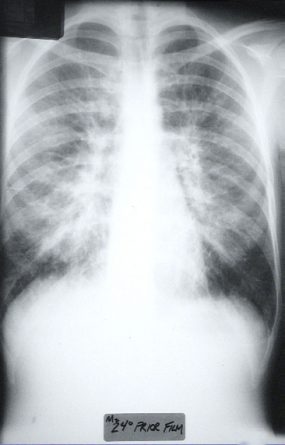

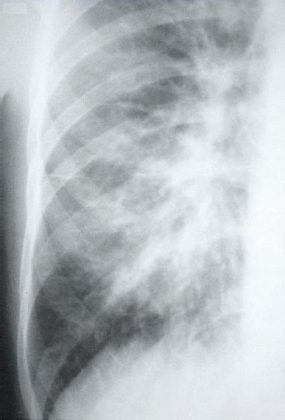

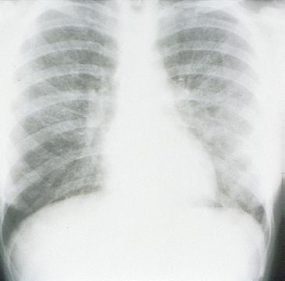

HPS has a characteristic radiological evolution, beginning with minimal changes of interstitial pulmonary edema, progressing to alveolar edema with severe bilateral involvement. Pleural effusions are common and are often large enough to be evident radiographically. Heart size is usually normal. Cardiac silhouette size on chest radiographs is usually normal.

Approximately one-third of patients show evidence of pulmonary edema in the initial radiograph. Forty-eight hours after the initial radiograph, virtually all patients demonstrate interstitial edema and two-thirds have developed extensive bibasilar or perihilar airspace disease.

This radiograph shows the interstitial changes of early HPS. At the lung bases are Kerley B lines, short linear opacities which are perpendicular to the pleural surfaces. The longer linear opacities radiating from the lung hilum are known as Kerley A lines. Together these findings are classically seen in heart failure, but are also seen in HPS. Peribronchial cuffing is also seen well on this film. The bronchi viewed end on are surrounded by a “cuff” of edema. This makes the bronchi appear as prominent circular opacities, appearing as “ring-like” shapes next to pulmonary blood vessels.

The lack of peripheral distribution of the initial airspace disease, the prominence of interstitial edema and the presence of pleural effusions early in the disease process help distinguish HPS from ARDS. There is, however, overlap in the radiographic appearance of the two diseases. Atypical pneumonias such as that caused by mycoplasm pneumonia can produce radiographic findings similar to early HPS, although the clinical illness tends to be much less severe.

Hyperacute hypersensitivity reactions, mitral stenosis, acute myocardial infarctions, all can cause interstitial edema with a normal heart size, and are also in the radiologic differential diagnosis of early HPS.